Abstract

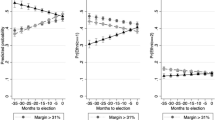

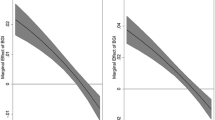

In countries with high levels of ethnic diversity, “nation building” has been proposed as a mechanism for integration and conflict reduction. We find no evidence of lower intensity of national sentiment in more ethnically fragmented countries or in minority groups. National feelings in a minority can be higher or lower than in a majority, depending on the degree of ethnic diversity of a country. On the one hand, in countries with high ethnic diversity, nationalist feelings are less strong in minority groups than in the majorities; on the other hand, in countries with low ethnic diversity, the reverse is true.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Mauro (1995) claims that ethnolinguistic diversity has a direct negative effect on the level of investment. Easterly and Levine (1997) find that a high level of ethnic fragmentation has a negative impact on economic growth. Montalvo and Reynal (2005) suggest that ethnic (and religious) polarization is one of the factors explaining economic development through its impact on the probability of civil wars. For a more accurate survey of the literature on the benefits and the costs of diversity, see Alesina and La Ferrara (2005).

The ethnic fractionalization index can be interpreted as measuring the probability that two randomly selected individuals in a country belong to different ethnic groups. The purpose of the ethnic polarization index is, instead, to capture how far the distribution of the ethnic groups is from a bipolar distribution, which represents the highest level of polarization.

National feeling at country level is measured as the proportion of individuals who choose to identify with their nation rather than with their ethnic group.

The relationship between education and identity is also explored by Aspachs-Bracons et al. (2008). They study how students in the Basque Countries sort into schooling systems based on parents’ identity.

Li (2010) uses World Values data and minority–majority categorizations to study the impact of social identities on tax attitudes.

In the case of Canada, we use a question about the language spoken at home to further distinguish between French Canadian and English Canadian.

Jordan is an exception. The ruling ethnic group is the Jordanian group, which is actually slightly smaller than the Palestinian group, a historically discriminated group. In this case, we classify Palestinian as the minority and Jordanian as the majority. The results are robust to the exclusion of Jordan from the dataset, however.

In the case of Bulgaria, there are 168 income categories rather than the standard 10; in the case of Macedonia (wave III), there are 88 categories. In the fourth wave in Macedonia, income is coded in the standard way.

Ethnic groups in Fearon’s dataset are identified sometimes in terms of language and sometimes in terms of race. Although it would be interesting to separate the effects of race and language, the small size of the sample (number of countries included) does not allow this.

For instance, we omit countries such as South Africa where there is a discrepancy between the WVS and Fearon’s dataset. Fearon’s dataset codes 14 South African groups (Gname, Zulu, Xhosa, North Sotho, Tswana, Coloured, Afrikaner, South Sotho, English-Speaking, Tsonga, Swazi, Asian, Venda, Ndebele), the WVS only four groups (white, black, colored, and Indian), which makes it impossible to interpret the coefficient of the interaction term between the variable “minority” and the country level of diversity (this coefficient is crucial for our purposes as explained in the next section).

See Montalvo and Reynal (2005) for a detailed discussion.

Descriptive statistics refer to the sample excluding Bulgaria and Macedonia (III wave).

The results reported in Table 4 are robust to the exclusion from the dataset of the three countries (Bosnia, Indonesia, and Jordan) where the ethnic majority represents less than 50% of the population.

The survey was conducted by interviewers who were not affiliated to any political party or government, making it likely that the survey was not perceived as related to a national institution.

This is consistent with the positive association found between income and national feeling.

Bauer et al. (2000) suggest that attitudes of the native population toward immigration is likely to be related to whether immigrants are selected according to the needs of the labor markets.

Members of an ethnic group might be expected to consume a specific ethnic good as defined by Chiswick (2009), respect a specific dress code (e.g., the Islamic veil) or a particular diet, as discussed by Epstein (2006, unpublished manuscript). Norms can involve the use of the local language at home (Lazear 1999) or participation in rituals and festivals (Kuran 1998).

Similar assumptions are made by Bisin et al. (2006) and Akerlof (1980). Kandel and Lazear (1992) discuss the relationship between firm size and peer pressure; they suggest that the level of monitoring may increase with the size of the firm and also that if more workers observe an individual, the sanctions imposed might be greater.

See Esteban and Ray (1994).

References

Akerlof GA (1980) A theory of social custom of which unemployment may be one consequence. Q J Econ 94(4):749–775

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2000) Economics and identity. Q J Econ 115(3):715–753

Alesina A, Baqir R, Easterly W (2000) Redistributive public employment. J Urban Econ 48(2):219–241

Alesina A, La Ferrara E (2005) Ethnic diversity and economic performance. J Econ Lit 43(3):762–800

Aspachs-Bracons O, Clots-Figueras I, Masella P (2008) Compulsory language educational policies and identity formation. J Eur Econ Assoc 6(2–3):434–444

Avitabile C, Clots-Figueras I, Masella P (2010) The effect of birthright citizenship on parental integration outcomes. CSEF working paper no. 246

Bannon A, Miguel E, Posner D (2004) Sources of ethnic identification in Africa. Afrobarometer working paper no. 44

Bauer T, Lofstrom M, Zimmermann KF (2000) Immigration policy, assimilation of immigrants and natives’ sentiments towards immigrants: evidence from 12 OECD-countries. Swed Econ Policy Rev 7(2):11–53

Bisin A, Verdier T (2000) The economic of cultural transmission and the dynamics of preferences. J Econ Theory 97(2):298–319

Bisin A, Patacchini E, Verdier T, Zenou Y (2006) ‘Bend it like Beckam’: identity, socialization and assimilation. CEPR discussion paper no. 5662

Bisin A, Patacchini E, Verdier T, Zenou Y (2008) Are Muslim immigrants different in terms of cultural integration? J Eur Econ Assoc 6(2–3):445–456

Caselli F, Coleman W (2006) On the theory of ethnic conflict. NBER working paper no. W12125

Charness G, Rigotti L, Rustichini A (2007) Individual behavior and group membership. Am Econ Rev 97(4):1340–1352

Chen Y, Li SX (2009) Group identity and social preferences. Am Econ Rev 99(1):431–457

Chiswick C (2009) The economic determinants of ethnic assimilation. J Popul Econ 22(4):859–880

Chiswick B, Miller P (1999) Language skills and earnings among legalized aliens. J Popul Econ 12(1):63–89

Clots-Figueras I, Masella P (2010) Education, language and identity. Mimeo

Constant A, Gataullina L, Zimmermann KF (2008) Ethnosizing immigrants. J Econ Behav Organ 69(3):274–287

Constant A, Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (2009) Attitudes towards immigrants, other integration barriers, and their veracity. Int J Manpow (Emerald Group Publishing) 30(1/2):5–14

Deutch K, Foltz W (1963) Nation building. Atherton, New York

Dustmann C, Preston I (2001) Attitudes to ethnic minorities, ethnic context, and location decisions. Econ J 111(470):353–373

Dustmann C (1996) The social assimilation of immigrants. J Popul Econ 9(1):37–54

Easterly W, Levine R (1997) Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ 112(4):1203–1250

Esteban J, Ray D (1994) On the measurement of polarization. Econometrica 62(4):819–8510

Fearon J (2003) Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. J Econ Growth 8(2):195–222

Georgiadis A, Manning A (2009) One nation under a groove? Multiculturalism in Britain. CEPR discussion paper no. 994

Kandel E, Lazear EP (1992) Peer pressure and partnerships. J Polit Econ 100(4):801–817

Kreuger A, Pischke JS (1997) A statistical analysis of crime against foreigners in unified Germany. J Hum Resour 32(1):182–209

Kuran T (1998) Ethnic norms and their transformation through reputational cascades. J Legal Stud 27(2):623–659

Li XS (2010) Social identities, ethnic diversity, and tax morale. Public Finance Rev 38(2):146–177

Lazear E (1999) Culture and language. J Polit Econ 107(S6):S95-29

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110(3):681–712

Manning A, Roy S (2009) Culture clash or culture club? National identity in Britain. Econ J 120(542):F72–F100

Miguel E (2004) Tribe or nation? Nation-building and public goods in Kenya versus Tanzania. World Polit 56(3):327–362

Montalvo J, Reynal M (2005) Ethnic diversity and economic development. J Dev Econ 76(2):293–323

Tilly C (1975) The formation of national States in Western Europe. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Acknowledgements

I am especially indebted to Francesco Caselli and Maitreesh Ghatak for their support. I also thank three anonymous referees, the editor Klaus F. Zimmermann, Oriana Bandiera, Erland Berg, Tim Besley, Matteo Cervellati, Raja Khali, Eliana La Ferrara, Andrea Prat, and participants at NEUDC conference 2006, “Polarization and Conflict” conference 2006 and seminars at LSE. All errors are mine. I also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the Collaborative Research Center 884.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Definition of variables

-

National identity: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent says “I am an American first and a member of some ethnic group second” (US example). Source: WVS

-

Minority: dummy equal to 0, if the ethnic group to which the individual belongs is the largest in the country; otherwise, it is equal to 1. Each interviewer has been asked to code the ethnic group of each individual in the sample. Source: WVS

-

Age: age of the respondent. Source: WVS

-

Female: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is female. Source: WVS

-

Primary: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent has, at most, primary school education. Source: WVS

-

Married: dummy equal to 1, if respondent is married. Source: WVS

-

Income: Proxy for individual income stream (not disposable). There are 10 income categories (net of transfers and taxes); they have been coded by deciles for each country, 1 = lowest decile; 10 = highest decile. Source: WVS

-

Employer > 10: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is employer/manager of an establishment with 10 or more employees. Source: WVS

-

Employer < 10: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is employer/manager of an establishment with less than10 employees. Source: WVS

-

Professional: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is a professional worker, lawyer, accountant, teacher, etc. Source: WVS

-

Supervisor: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is a supervisory, non-manual office worker. Source: WVS

-

Office: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is a non-supervisory, non-manual office worker. Source: WVS

-

Foreman: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is a foreman and supervisor. Source: WVS

-

Skilled: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is a skilled manual worker Source: WVS

-

Semi-skilled: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is a semi-skilled manual worker. Source: WVS

-

Unskilled: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is an unskilled manual worker. Source: WVS

-

Farmer: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent has his/her farm. Source: WVS

-

Armed forces: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent is a member of armed forces. Source: WVS

-

Never job: dummy equal to 1, if the respondent never had a job. Source: WVS

-

Size: size of ethnic group to which the individual belongs. Source: Fearon’s dataset

-

Etfra: country index of ethnic fractionalization. Source: Fearon’s dataset

-

Etpol: country index of ethnic polarization. Source: Fearon’s dataset

1.2 Countries and ethnic groups

Albania (wave IV): Albanian, Greek, other; Armenia (wave III): Armenian, Russian, other; Azerbaijan (wave III): Azerbaijanian, Russian, other; Belarus (wave III): Belarusian, Russian, Polish, Ukranian, other; Bosnia (wave IV): Bosniak, Serbs, Croats, other; Brazil (wave III): white, mulatto, black, other; Bulgaria (wave III): Bulgarian, Roma, Turkish, other; Canada (wave IV): English Canadian, French Canadian, black, South Asian, Chinese, East Asian, indigenous peoples, other; China (wave II): Han, other; Georgia (wave III): Georgian, other; Indonesia (wave IV): Javanese, Malay, Chinese, Sundanese, other; Israele (wave IV): Jewish, Arabic; Jordan (wave IV): Jordanian, Palestinian, other; Latvia (wave III): Latvian, Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, Polish, other; Macedonia (waves III–IV): Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish, Roma, Serb, other; Moldova (wave III): Moldovian, Slavs, Bulgarian, Gaugas; Pakistan (wave IV): Punjabi, Baluchi, Sindhi, Urdu speaking, other; Singapore (wave IV): Malay, Indian, South Asian, Chinese, other; Spain (waves III–IV): Castillano, Catalan, Basque, Galician, other; Uruguay (waveIV): white, black, other; US (waves II–III–IV): white, black, Asian, Hispanic, other.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masella, P. National identity and ethnic diversity. J Popul Econ 26, 437–454 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-011-0398-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-011-0398-0