Abstract

Purpose

Microbiological diagnosis (MD) of infections remains insufficient. The resulting empirical antimicrobial therapy leads to multidrug resistance and inappropriate treatments. We therefore evaluated the cost-effectiveness of direct molecular detection of pathogens in blood for patients with severe sepsis (SES), febrile neutropenia (FN) and suspected infective endocarditis (SIE).

Methods

Patients were enrolled in a multicentre, open-label, cluster-randomised crossover trial conducted during two consecutive periods, randomly assigned as control period (CP; standard diagnostic workup) or intervention period (IP; additional testing with LightCycler®SeptiFast). Multilevel models used to account for clustering were stratified by clinical setting (SES, FN, SIE).

Results

A total of 1416 patients (907 SES, 440 FN, 69 SIE) were evaluated for the primary endpoint (rate of blood MD). For SES patients, the MD rate was higher during IP than during CP [42.6% (198/465) vs. 28.1% (125/442), odds ratio (OR) 1.89, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43–2.50; P < 0.001], with an absolute increase of 14.5% (95% CI 8.4–20.7). A trend towards an association was observed for SIE [35.4% (17/48) vs. 9.5% (2/21); OR 6.22 (0.98–39.6)], but not for FN [32.1% (70/218) vs. 30.2% (67/222), P = 0.66]. Overall, turn-around time was shorter during IP than during CP (22.9 vs. 49.5 h, P < 0.001) and hospital costs were similar (median, mean ± SD: IP €14,826, €18,118 ± 17,775; CP €17,828, €18,653 ± 15,966). Bootstrap analysis of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio showed weak dominance of intervention in SES patients.

Conclusion

Addition of molecular detection to standard care improves MD and thus efficiency of healthcare resource usage in patients with SES.

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT00709358.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of sepsis is rising and the severe forms [severe sepsis (SES) including septic shock] are still a major cause of death [1, 2]. Patients requiring immunosuppressive therapy are more prevalent with febrile neutropenia (FN) being a frequent life-threatening complication [3]. Infective endocarditis is also increasing in incidence, with high mortality and morbidity [4, 5]. Early initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy reduces the morbidity and mortality of these severe infections, prompting the prescription of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents before the results of microbiological diagnosis (MD) are known [6–8]. This empirical first-line therapy is one of the factors explaining the increase in antimicrobial-resistance prevalence [9]. Moreover, antimicrobial therapy usually remains empirical, since microbial documentation in the blood is usually obtained for a maximum of 30% of cases for FN, and 35–50% for SES [10–13].

Blood cultures (BC) are still the main biological tools for identifying the microbial pathogen(s) associated with severe infections [14]. Their results are critical for the choice of an appropriate antimicrobial treatment, especially in cases of resistant bacteria [2, 15, 16]. However, their low positivity rates (10–20% overall) and delayed results (median 2–3 days) make them useful mostly for escalation or de-escalation in the days following the onset of sepsis [17, 18]. Molecular detection has been developed to provide a shorter time to results and to detect microbial nucleic acids in patients with receipt of antibiotic therapy [12]. Meta-analyses for testing molecular detection of pathogen in the blood have reported these tests as less sensitive and less specific than BCs, taken as the gold standard, and consequently these tests are rarely used in the diagnostic standard workup [19, 20]. It should be noted that in the previous studies, many cases were shown with positive molecular tests and BC-negative with clinical status showing signs of bloodstream infections [21, 22]. The cost-effectiveness of molecular direct testing in blood remains unknown [23].

We conducted a multicentre open-label cluster-randomised crossover clinical trial to assess the clinical and economic impact of molecular detection of pathogens in blood for patients with severe infections, such as SES, FN, and suspicion of infective endocarditis (SIE) [24]. Our hypothesis was that molecular direct testing, in addition to a conventional workup, would provide relevant and timely information for the adjustment of antimicrobial therapy and that the additional cost would be offset by successful infection management.

Methods

Study procedures and participants

The study was conducted in 55 clinical wards of 18 university hospitals (each hospital being a cluster) during two consecutive 6-month periods, randomly assigned as intervention (IP) or control (CP) (standard care) periods. Details of the protocol are provided in the supplementary text and at the clinical trials website (https://clinicaltrials.gov NCT00709358). Patients aged ≥18 years were consecutively enrolled when meeting the diagnosis of (1) SES (including septic shock) [1, 10] (2) a first episode of FN [3, 13] or (3) suspicion of infective endocarditis, as defined below.

During the two periods, at least two BC sets were collected within 24 h after inclusion [14]. During IP, direct molecular testing was additionally performed on blood using the CE-IVD LightCycler® SeptiFast test (LSF; Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) (see supplemental methods for details on testing). During the two periods, additional BCs and other specimens were submitted for microbiological examination at the discretion of the physician and processed following general guidelines [14]. The results of microbiological tests, including LSF tests during IP, were transmitted to clinical wards in a time-line for physicians to initiate or modify antimicrobial therapy following general recommendations [3, 7, 25].

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was MD, i.e. detection of pathogens in the blood samples using results of BCs during CP and of both BCs and molecular tests during IP.

Secondary endpoints included the pathogens identified, the turn-around time (TAT) (i.e., time interval from taking blood samples to transmission of results), and the number of patients receiving an appropriate treatment. Appropriateness was evaluated by comparing the pathogen detected and the list of antimicrobial agents prescribed within the 7 days after inclusion [3, 7, 25]. The complications were observed until the end of the study (EOS) (discharge, death, 30 days for SES and FN, 45 days for SIE). Costs were measured at the EOS.

Statistical analysis

The study was designed as a superiority trial. With the hypothesis of an effect modification by type of infection, the study was powered on the primary endpoint in subgroups of SES and FN. Assuming a documentation prevalence of 35–50% in SES [10] and 30% in FN, [11, 13], at least 480 and 440 patients in the SES and FN groups, respectively, were needed to show a 15% absolute difference, considering a two-sided type I error of 0.05, a type II error of 0.10, an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.01, and an 18-hospital number of clusters. Sample size was not estimated for SIE, since the overall number of cases was supposed to be lower than 150 [5].

Prevalence of the primary endpoint was compared between the two groups with the χ 2 test, and the absolute risk reduction (ARR) was calculated with their 95% confidence interval (CI). To account for clustering (confounding and effect modification by centre), a random-centre effect logistic regression (multilevel model with patients at level 1 and hospital at level 2) was analysed. To estimate the intervention effect, we computed the odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% CIs in a multilevel model, taking into account the order of intervention to control for a potential carryover effect.

Cost-effectiveness evaluation

The prospective economic evaluation was concurrent with the randomized trial, in accordance with the CHEERS (Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards) statement [26]. We estimated the incremental cost-effectiveness of using LSF in addition to a standard workup from the perspective of the hospital with a 30-day time horizon [27, 28]. Effectiveness was defined as the primary endpoint. Hospital resources were valued by adjusting the 2013 average national cost of each patient’s diagnosis related group (DRG) with their actual length of stay and resources used during their hospitalisation. Types of resources and unit costs are described in Supplementary Table 2. A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted to estimate incremental costs (difference in per-patient costs between groups) per incremental microbial documentation. The uncertainty of the results was analysed by the non-parametric bootstrap method to make multiple estimates of the ICER by randomly re-sampling the patient population to create sub-samples. Using this bootstrap analysis, the scatter plot of 1,000 ICERs is presented on the cost-effectiveness plane [29, 30]. Data reporting was performed according to CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines [31].

Results

Patients and primary outcome

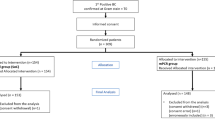

Of 1459 eligible patients, 1416 were included as 731 during IP and 685 during CP (Fig. 1), and as 907 (64%) with SES, 440 (31.1%) with FN, and 69 (4.9%) with SIE. Patient characteristics, depicted in Table 1, were not different between the two periods.

During IP, MD was positive for 285/731 (39.0%) patients compared with 193/685 (28.2%) during CP (P < 0.001) (Table 2). A higher MD rate was also significantly observed when excluding 41 cases with putative contaminants (e.g. one test positive with coagulase-negative staphylococci) observed at a rate of 2.7 and 3%, in CP and IP, respectively. Using multilevel modelling, neither centre-effect (P = 0.65) nor effect-modification by centre (P = 0.85) were observed, but a significant effect with regard to the subgroup of infection (P = 0.03). Kappa’s agreement between the results of molecular tests and those of BCs was poor (0.2693 ± 0.0366 SD) with only 83 patients with both positive molecular test and BCs in the IP.

Among patients suffering from SES, 198/464 (42.6%) patients had MD during IP, compared with 124/442 (28.1%) during CP (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.43–2.50, P < 0.001). The intervention resulted in an absolute increase in the MD rate by 14.5% (95% CI 8.4–20.7). MD was significantly associated with the primary site of infection being other than pulmonary, with community-acquired infection and with severity criteria (Table 3). Multivariate analysis adjusted for these variables did not change the association between the IP and the MD rate (OR 1.89; 95% CI 1.36–2.63, P = 0.001).

The MD rate was similar for patients with FN, and only a trend for an association was observed among patients with SIE (Table 2).

Secondary outcomes

Pathogens identified

The use of the molecular test resulted in a significantly higher number of patients in whom Gram-negative bacilli (GNB), Gram-positive cocci (GPC), or fungi were detected in their blood (Table 2; Fig. 2). This was observed in the whole population, as well as in patients with SES [19.6 vs. 11.5% for GNB, P < 0.001; 23.7 vs. 15.6% for GCP, P = 0.002; and 2.8% (13 cases) vs. 0.7% (3 cases) for fungi, P = 0.02, for IP and CP, respectively]. The detection of bacterial species not included in LSF (e.g., strict anaerobes, Salmonella spp., Bacillus spp. and others) was similar in the two periods (P = 0.18). Polymicrobic infections (concomitant detection of more than one pathogen in the blood) were more often detected during IP [160/731 (22%) vs. 75/685 (11%), P = 0.001). The pathogens detected during the two periods are detailed in Table 4.

Venn diagram presenting the microbial diagnosis given by blood cultures (BC) and the molecular test (LSF) for patients during the intervention period. GNB Gram-negative bacilli (enterobacteria, acinetobacter and pseudomonades), GPC Gram-positive cocci (staphylococci, streptococci and enterococci), blue circle BC positive cases, green circle positive molecular test. Cases could be diagnosed with more than one pathogen

Time interval from blood collection to results

Among the patients with positive MD, the median TAT from blood collection to technical validation on the one hand and to transmission to the clinicians on the other hand, were significantly shorter during IP (Table 2). It has to be noted that, for patients with SES, the median TAT was below 24 h. Results were first transmitted by telephone (73.6%), computer interface (23.6%), Fax (14.5%), and mailing (10.9%). Interaction between laboratories and wards was as usual for discussion of the results.

Appropriate antimicrobial treatment

Considering the 1416 included patients, antimicrobial agents prescribed were beta-lactams (95.5%), aminoglycosides (43.2%), fluoroquinolones (26.5%), glycopeptides (21.1%), other antibiotics (31.7%), and antifungal agents (17.7%), with no difference between the two periods (Supplementary Table 3). In this whole population, a significantly higher number of patients received an appropriate therapy during IP (Table 2). However, when only the 478 patients with positive MD were considered, the rates of appropriate therapy were similar for the two periods (90.5 and 90.2%, respectively). An optimal treatment, i.e. more targeted towards the etiological microbes was observed in 263/395 (66.6%) patients with no difference between CP and IP (70.7 and 63.9%, P = 0.16) (supplementary figure). During IP, when 285 cases were observed as MD-positive, clinicians attested they modified the antimicrobial treatment according to the LSF results in 29.4% (79/269 answers) out of which de-escalation was done for 49 cases (62%).

Complications and mortality

Complications were observed in 362 cases (31.7% of 1142 patients documented for complications) as an extension of the infection (n = 190, 16.6%) or a new infection episode (n = 172, 15.1%), with no difference between the two periods [32.1% (185/577) and 29.6% (167/565), P = 0.34]. Among SES patients, the 7-day mortality rate was 17.3% (149/863) with no significant difference between the two periods (18.7 vs. 15.8% in IP and CP, respectively; P = 0.38), even when analyses were adjusted for confounders (Supplementary Table 4). We checked that there were no relation between the positivity of the molecular test and mortality.

Economic evaluation

The cost-effectiveness analysis used information from all patients with complete primary outcome and cost data. Resource utilisation and costs are presented in Table 5. The costs associated with the molecular test were calculated at an average of €475.20 per test including technician time, with each patient having an average of 1.9 tests. There were no significant differences between the two periods even for investigations or number of days with antimicrobial treatment (13.1 days in both periods) (Table 5). Median total costs were €14,826 vs. €17,828, for IP and CP, respectively (P = 0.8). Sub-group analyses by disease did not show a cost difference either.

Figure 3 shows the cost-effectiveness of the molecular test as a scatterplot of mean cost and effect differences. The key uncertainty that drove the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was the size of the effectiveness effect, represented on the horizontal axis. The difference in effectiveness was evenly distributed on each side of the vertical axis for patients with FN, indicating no benefit during IP. The scatterplot for patients with SES indicated a weak dominance with a positive effectiveness effect and a reduced hospital cost as shown by the higher density below the horizontal axis.

Discussion

In this multicentre cluster-randomised crossover trial including 1416 patients, we found that adding direct molecular detection of pathogens in the blood of patients hospitalised with severe sepsis resulted in an overall higher microbial diagnosis rate than with conventional diagnosis, which was made on the basis of blood cultures. Moreover, the time to results was shorter in the IP, leading to bacteremia and fungemia being diagnosed in less than 24 h in most cases, without an increase in hospital costs.

In patients with severe infections, since the pathogen is recovered at most in 50%, the others are treated by empirical antimicrobial regimens without consideration of appropriateness or de-escalation being possible [1, 32]. Direct detection of microbial pathogens in the blood was developed in the 2000s to circumvent culture limitations [33]. LSF was the first commercial kit to provide standardisation and enable comparisons between studies [12, 34]. Since its clinical performance was mostly compared with blood cultures [22], meta-analyses concluded that it had a lack of sensitivity (68%) and specificity (86%) leading to abandoning the test [19, 20]. However, results which were seen as false-positives, i.e. low specificity, were also seen as true-positives when the clinical status was the gold standard (septic shock, for instance) or when the LSF results were compared with biomarkers of infection [12, 19, 35]. The presence of dormant or non-cultivable microbes in the blood can also explain the discrepancy, as well as the fact that most patients have already received antimicrobial agents, leading to false-negative BCs [36]. This raised the question of whether blood cultures can still be considered the gold standard for documenting bloodstream infections. It is also known that, with regard to clinical status, BCs show a lack of specificity (one-third are falsely positive due to contaminants, leading to excess treatment) and sensitivity (at least half of them are falsely negative in patients with severe infections) [9–12, 37]. We therefore decided to investigate the relevance of the molecular detection of pathogens in an interventional study with the aetiological microbial diagnosis as the primary outcome, whatever the assay—blood culture or molecular test—providing the positive result. We hypothesised that adding molecular detection to conventional cultures would increase the number of cases with microbiological documentation.

The results we obtained in the CP for positive detection of pathogens in the blood were concordant with previous studies on large cohorts of severe sepsis, with similar severity scores and mortality rates, even with recent studies using the new definitions of sepsis [10, 38]. For FN, the positivity rate was also concordant with previous studies conducted on first episodes of FN, which is much higher than in secondary episodes [11, 13]. This high rate of positivity in the blood during IP is similar to that described in previous studies on direct molecular detection where infections were as severe as in our study [12].

Because the aetiological microbes were more often documented in the IP, we looked at the consequences on the prescription of antimicrobial agents to treat the infection. We did not observe significant differences in prescription, either quantitatively (number of patients with treatment and cost per patient) or qualitatively (antimicrobial spectra), even for SES cases. This was probably because the treatment was not protocolled according to the pathogen identification, and the LSF test did not provide susceptibility results more than methicillin resistance of staphylococci [1, 3, 25]. It may also be due to the intervention itself, since polymicrobial infections and fungal infections were more often diagnosed, requiring broad-spectrum antibacterial agents and, in some cases, the addition of antifungal agents. Lastly, we did not detail the dosage of the agents, which was shown recently to be underestimated in most patients with severe infections [39]. Patients were managed under standard care conditions and, although the therapeutic approach may have varied between investigators, ward, and hospital centres, the results were mostly dependent upon the type of infection, and not the centre. The outcome was similar between the two periods, with a mortality rate concordant with the severity scores at inclusion [1, 10].

Because most molecular tests are more expensive than blood cultures, we investigated the cost of implementing systematic molecular detection in blood in addition to standard care. In a previous study, the cost was lower (€32,228 vs. €42,198) for 48 patients having LSF plus BC versus 54 patients having only BC [40]. In our study, the addition of LSF provided only a trend for lower hospital costs and higher effectiveness (i.e., microbiological diagnostic yield) for patients with SES. This was probably because the length of ICU stay was not affected by the earlier identification of micro-organisms, as also observed in other studies [8].

Limitations and strengths

There are two main limitations of our study. The first is that we present our results in 2016 when sepsis definitions have changed [41]. The strengths of our study remain since the patient characteristics were as severe as recent cohorts examined with the new sepsis criteria [8, 38]. The second limitation is the LSF test itself since it does not provide antimicrobial susceptibility testing results, as well as the most recent kits of this kind [42, 43]. Consequently, although MD was obtained for more patients and more rapidly during IP, we did not observe any difference in the antimicrobial treatment and outcomes. A recent controlled study showed that reducing TAT to pathogen identification in BCs, without specific AST as in our study, was able to decrease the prescription of broad-range antimicrobials and to increase de-escalation and appropriate escalation, at the condition that antibiotic stewardship is also provided [44], which was not done in our study. Minor weaknesses of the study concerns the suspicion of endocarditis, because the number of patients was too low to yield any conclusions since infective endocarditis infections are fairly rare (1/100,000 cases observed yearly) and their diagnosis, according to Duke and Li definitions, already includes microbiological results from BCs and from culture of removed valves [4]. Here, we aimed to include patients before diagnosis as we sought to include more documentation (i.e., we increased the number of cases with definite infective endocarditis). Although there was a trend in association, the numbers of patients with SIE were too small to show significant differences and a specific study for this indication is needed. Although we were disappointed by the results for patients with a first episode of FN, they confirmed the results of previous smaller studies [11, 34]. It was suggested that, in FN, the diagnostic yield of molecular detection could be higher in patients already receiving antimicrobial agents, i.e., at the second or later febrile episode, rather than in naïve patients. Regarding the lack of benefit for documenting FN, other assays should be explored and the infectious nature of the associated fever may need to be reconsidered.

The strengths of our study are the following. This is the first randomised interventional study on the use of direct molecular detection of pathogens in the blood by a commercial test. The originality of this study is that we did not compare results of the molecular test to those of blood cultures taken as the gold standard, but instead evaluated what direct molecular testing brings in standard care with regard to clinical status assessing the primary outcome of microbial diagnosis. Strengths of the study also include its size and design. The study was planned as a cluster-randomised trial because of practical (cost of equipment and technical staff) and organisational (training of laboratory technicians on-site) constraints. This design allowed the optimisation of compliance with the assigned strategy. A common pitfall of cluster-randomised trials is an imbalance in patient characteristics and patient management. Therefore, we planned a crossover design to minimise imbalance between groups, and randomised the order of intervention. This crossover design was suitable because there was low risk of a carryover effect. We obtained comparable baseline characteristics of severe sepsis groups during the two periods and adjustment for potential confounders did not change the results of the crude analysis. The strengths also include the molecular test itself since the main limiting factor of molecular tests in direct diagnosis is their analytical sensitivity, i.e. their ability to detect bacterial and fungal DNA without natural amplification by culture. LSF is one of the rare tests that can reproducibly detect 100 CFU/ml. The future test should be as sensitive as LSF but should detect resistance genes.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated, in a multicentre randomised controlled trial, that performing molecular detection of pathogens in addition to standard care of blood cultures, increases the number of septic patients with microbial diagnosis, and shortens the time to start a species-specific antimicrobial therapy. A step further is now necessary with molecular antimicrobial resistance testing combined with protocolled strategy with regard to epidemiological data of the centre or stewardship for antimicrobial agents. This can bring more impact, especially in cases of infection caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens [44].

References

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb S, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R (2013) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 39:165–228

de Kraker ME, Jarlier V, Monen JC, Heuer OE, van de Sande N, Grundmann H (2013) The changing epidemiology of bacteraemias in Europe: trends from the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:860–868

Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, Mullen CA, Raad, II, Rolston KV, Young JA, Wingard JR, Infectious Diseases Society of A (2011) Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 52:e56–e93

Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG Jr, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR (2000) Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 30:633–638

Duval X, Delahaye F, Alla F, Tattevin P, Obadia JF, Le Moing V, Doco-Lecompte T, Celard M, Poyart C, Strady C, Chirouze C, Bes M, Cambau E, Iung B, Selton-Suty C, Hoen B (2012) Temporal trends in infective endocarditis in the context of prophylaxis guideline modifications: three successive population-based surveys. J Am Coll Cardiol 59:1968–1976

Shorr AF, Micek ST, Welch EC, Doherty JA, Reichley RM, Kollef MH (2011) Inappropriate antibiotic therapy in Gram-negative sepsis increases hospital length of stay. Crit Care Med 39:46–51

Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, Light B, Parrillo JE, Sharma S, Suppes R, Feinstein D, Zanotti S, Taiberg L, Gurka D, Kumar A, Cheang M (2006) Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 34:1589–1596

Timsit JF, Citerio G, Bakker J, Bassetti M, Benoit D, Cecconi M, Curtis JR, Hernandez G, Herridge M, Jaber S, Joannidis M, Papazian L, Peters M, Singer P, Smith M, Soares M, Torres A, Vieillard-Baron A, Azoulay E (2014) Year in review in Intensive Care Medicine 2013: III. Sepsis, infections, respiratory diseases, pediatrics. Intensive Care Med 40:471–483

Bell BG, Schellevis F, Stobberingh E, Goossens H, Pringle M (2014) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect Dis 14:13

Brun-Buisson C, Meshaka P, Pinton P, Vallet B (2004) EPISEPSIS: a reappraisal of the epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis in French intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 30:580–588

Pautas C, Sbidian E, Hicheri Y, Bastuji-Garin S, Bretagne S, Corbel C, Gregoire L, Maury S, Merabet L, Cordonnier C, Cambau E (2012) A new workflow for the microbiological diagnosis of febrile neutropenia in patients with a central venous catheter. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:943–946

Reinhart K, Bauer M, Riedemann NC, Hartog CS (2012) New approaches to sepsis: molecular diagnostics and biomarkers. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:609–634

Cordonnier C, Buzyn A, Leverger G, Herbrecht R, Hunault M, Leclercq R, Bastuji-Garin S (2003) Epidemiology and risk factors for gram-positive coccal infections in neutropenia: toward a more targeted antibiotic strategy. Clin Infect Dis 36:149–158

Baron EJ, Miller JM, Weinstein MP, Richter SS, Gilligan PH, Thomson RB Jr, Bourbeau P, Carroll KC, Kehl SC, Dunne WM, Robinson-Dunn B, Schwartzman JD, Chapin KC, Snyder JW, Forbes BA, Patel R, Rosenblatt JE, Pritt BS (2013) A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM)(a). Clin Infect Dis 57:e22–e121

Tabah A, Koulenti D, Laupland K, Misset B, Valles J, Bruzzi de Carvalho F, Paiva JA, Cakar N, Ma X, Eggimann P, Antonelli M, Bonten MJ, Csomos A, Krueger WA, Mikstacki A, Lipman J, Depuydt P, Vesin A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Zahar JR, Blot S, Carlet J, Brun-Buisson C, Martin C, Rello J, Dimopoulos G, Timsit JF (2012) Characteristics and determinants of outcome of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care units: the EUROBACT International Cohort Study. Intensive Care Med 38:1930–1945

See I, Freifeld AG, Magill SS (2016) causative organisms and associated antimicrobial resistance in healthcare-associated, central line-associated bloodstream infections from oncology settings, 2009–2012. Clin Infect Dis 62:1203–1209

Madaras-Kelly K, Jones M, Remington R, Caplinger C, Huttner B, Samore M (2015) Description and validation of a spectrum score method to measure antimicrobial de-escalation in healthcare associated pneumonia from electronic medical records data. BMC Infect Dis 15:197

Garnacho-Montero J, Gutierrez-Pizarraya A, Escoresca-Ortega A, Corcia-Palomo Y, Fernandez-Delgado E, Herrera-Melero I, Ortiz-Leyba C, Marquez-Vacaro JA (2014) De-escalation of empirical therapy is associated with lower mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med 40:32–40

Dark P, Blackwood B, Gates S, McAuley D, Perkins GD, McMullan R, Wilson C, Graham D, Timms K, Warhurst G (2014) Accuracy of LightCycler((R)) SeptiFast for the detection and identification of pathogens in the blood of patients with suspected sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 41:21–33

Chang SS, Hsieh WH, Liu TS, Lee SH, Wang CH, Chou HC, Yeo YH, Tseng CP, Lee CC (2013) Multiplex PCR system for rapid detection of pathogens in patients with presumed sepsis—a systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 8:e62323

Avolio M, Diamante P, Modolo ML, De Rosa R, Stano P, Camporese A (2014) Direct molecular detection of pathogens in blood as specific rule-in diagnostic biomarker in patients with presumed sepsis: our experience on a heterogeneous cohort of patients with signs of infective systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Shock 42:86–92

Ratzinger F, Tsirkinidou I, Haslacher H, Perkmann T, Schmetterer KG, Mitteregger D, Makristathis A, Burgmann H (2016) Evaluation of the Septifast MGrade test on standard care wards-a cohort study. PLoS ONE 11:e0151108

Cambau E, Bauer M (2015) Multi-pathogen real-time PCR system adds benefit for my patients: yes. Intensive Care Med 41:528–530

Cambau E, Durand-Zaleski I, Bretagne S, Brun-Buisson C, Cordonnier C, Duval X, Herwegh S, Pottecher J, Courcol R, Bastuji-Garin S, The Evamica study team (2013) Performance and economic evaluation of the molecular detection of pathogens for patients with severe infections: the EVAMICA open-label cluster-randomised interventional crossover trial. ESCMID, Berlin, number 0673/3398

Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, Thuny F, Prendergast B, Vilacosta I, Moreillon P, de Jesus AM, Thilen U, Lekakis J, Lengyel M, Muller L, Naber CK, Nihoyannopoulos P, Moritz A, Zamorano JL (2009) Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur Heart J 30:2369–2413

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E, Force CT (2013) Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Value Health 16:e1–e5

O’Brien BJ, Briggs AH (2002) Analysis of uncertainty in health care cost-effectiveness studies: an introduction to statistical issues and methods. Stat Methods Med Res 11:455–468

Briggs AH, O’Brien BJ (2001) The death of cost-minimization analysis? Health Econ 10:179–184

Briggs AH, Mooney CZ, Wonderling DE (1999) Constructing confidence intervals for cost-effectiveness ratios: an evaluation of parametric and non-parametric techniques using Monte Carlo simulation. Stat Med 18:3245–3262

Black WC (1990) The CE plane: a graphic representation of cost-effectiveness. Med Decis Making 10:212–214

Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Group C (2012) Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 345:e5661

Averbuch D, Orasch C, Cordonnier C, Livermore DM, Mikulska M, Viscoli C, Gyssens IC, Kern WV, Klyasova G, Marchetti O, Engelhard D, Akova M (2013) European guidelines for empirical antibacterial therapy for febrile neutropenic patients in the era of growing resistance: summary of the 2011 4th European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Haematologica 98:1826–1835

Peters RP, van Agtmael MA, Danner SA, Savelkoul PH, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM (2004) New developments in the diagnosis of bloodstream infections. Lancet Infect Dis 4:751–760

Varani S, Stanzani M, Paolucci M, Melchionda F, Castellani G, Nardi L, Landini M, Baccarani M, Pession A, Sambri V (2009) Diagnosis of bloodstream infections in immunocompromised patients by real-time PCR. J Infect 58:346–351

Bloos F, Sachse S, Kortgen A, Pletz MW, Lehmann M, Straube E, Riedemann NC, Reinhart K, Bauer M (2013) Evaluation of a polymerase chain reaction assay for pathogen detection in septic patients under routine condition: an observational study. PLoS ONE 7:e46003

Potgieter M, Bester J, Kell DB, Pretorius E (2015) The dormant blood microbiome in chronic, inflammatory diseases. FEMS Microbiol Rev 39:567–591

Hall KK, Lyman JA (2006) Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev 19:788–802

SepNet Critical Care Trials G (2016) Incidence of severe sepsis and septic shock in German intensive care units: the prospective, multicentre INSEP study. Intensive Care Med 42:1980–1989

Bassetti M, De Waele JJ, Eggimann P, Garnacho-Montero J, Kahlmeter G, Menichetti F, Nicolau DP, Paiva JA, Tumbarello M, Welte T, Wilcox M, Zahar JR, Poulakou G (2015) Preventive and therapeutic strategies in critically ill patients with highly resistant bacteria. Intensive Care Med 41:776–795

Alvarez J, Mar J, Varela-Ledo E, Garea M, Matinez-Lamas L, Rodriguez J, Regueiro B (2012) Cost analysis of real-time polymerase chain reaction microbiological diagnosis in patients with septic shock. Anaesth Intensive Care 40:958–963

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC (2016) The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315:801–810

Menezes LC, Rocchetti TT, Bauab Kde C, Cappellano P, Quiles MG, Carlesse F, de Oliveira JS, Pignatari AC (2013) Diagnosis by real-time polymerase chain reaction of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes in bone marrow transplant patients with bloodstream infections. BMC Infect Dis 13:166

Stevenson M, Pandor A, Martyn-St James M, Rafia R, Uttley L, Stevens J, Sanderson J, Wong R, Perkins GD, McMullan R, Dark P (2016) Sepsis: the LightCycler SeptiFast Test MGRADE(R), SepsiTest and IRIDICA BAC BSI assay for rapidly identifying bloodstream bacteria and fungi: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 20:1–246

Banerjee R, Teng CB, Cunningham SA, Ihde SM, Steckelberg JM, Moriarty JP, Shah ND, Mandrekar JN, Patel R (2015) Randomized trial of rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based blood culture identification and susceptibility testing. Clin Infect Dis 61:1071–1080

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the technicians who performed the microbiological tests, and all the clinical colleagues not cited in the Evamica study team and who helped with the patients.

List of collaborators of the EVAMICA study team

Centre APHP-Beaujon, Clichy, France: Agnès Lefort, Jean Mantz, Sébastien Pease, Leïla Lavagna, Marie Hélène Nicolas-Chanoine, Véronique Leflon, Estelle Marcon.

Centre APHP-Bichat, Paris, France: Raymond Ruimy, Antoine Andremont, Jacques Lebras, Bernard Iung, Bernard Regnier, Patrick Yeni, Philippe Montravers, Bruno Mourvillier, Emila Ilic-Habensus, Nadia El Alami Talbi, Sigismond Lasocki.

Centre APHP-Cochin, Paris, France: Didier Bouscary, Jean-Paul Mira, David Grimaldi, Nathalie Marin, Alexandra Doloy, Claire Poyart.

Centre APHP-Henri Mondor, Créteil, France: Emmanuel Scherrer, Cecile Chambon-Pautas, Fabrice Cook, Armand Mekontso-Dessap, Frédérique Schortgen, Karine Chedevergne.

Centre APHP-Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France: Jean-Paul Vernant, Liliane Gauvin-Bodin, Jean-Louis Trouillet, Jean Chastre, François Bricaire, Nathalie Dheder, Ania Nieszkowska, Annick Datry, Arnaud Fekkar, Pierre Buffet, Rommy Mazier, Sophie Brun, Vanina Meyssonnier, Florence Brossier, Vincent Jarlier.

Centre APHP-Saint Antoine, Paris, France: Françoise Isnard, Jean-Luc Baudel, Jean-Luc Meynard, Valérie Lalande, Jean-Claude Petit, Patricia Roux.

Centre APHP-Saint Louis, Paris, France: Emmanuel Raffoux, Patricia Ribaud, Vincent Das, Benoit Schlemmer, Elie Azoulay, Luc Chimot, Jean-Michel Molina, Diane Ponscarme, Juliette Pavie, Isabelle Casin, Jean Menotti, François Simon.

Centre CHU Pellegrin, Bordeaux, France: Didier Gruson, Emilie Bessède, Emmanuelle Guilhon, Isabelle Accoceberry, Pascal Millet, Cécile Bébéar.

Centre CHU Morvan and Cavale Blanche, Brest, France: Christian Berthoux, Jean-Marie Tonnelier, Michel Garre, Geneviève Hery-Arnaud, Christopher Payan, Gilles Nevez.

Centre CHU Michallon, Grenoble, France: Jean-Francois Timsit, Jean-Yves Cahn, Jean-Paul Brion, Bernard Le Beau, Danièle Maubon, Hervé Pelloux, Max Maurin, Olivier Epaulard, Rebecca Hamidfar.

Centre CHRU Lille, France: Céline Berthon, Valérie Coiteux, Louis Terriou, Saadalla Nseir, Jean-Luc Auffray, Jean-Pierre Jouet, Alain Durocher, Karine Faure, Daniel Camus.

Centre CHU Dupuytren, Limoges, France: Anthony Dugard, Chantal Tisseuil, Cécile Duchiron, Daniel Ajzenberg, Dominique Bordessoule, Fabien Garnier, Bruno François, Marie-Cécile Ploy, Marie-Laure Darde, Marie-Pierre Chaury, Stéphane Girault, Arnaud Jaccard, Stéphane Moreau, Liliane Réménieras, Mohamed Touati, Pascal Turlure, Jean-Bernard Amiel, Marc Clavel, Anthony Dugard, Nicolas Pichon, Déborah Postil, Philippe Vignon.

Centre CHU la Croix Rousse, Lyon, France: Daniel Espinouse, Didier Jacques, Frédérique De Monbrison, Jean-Michel Grozel, Monique Chomarat, Pierre-Yves Gueugniaud, Rokiatou Sanogo.

Centre CHU La Timone, Marseille, France: Michel Drancourt, Pierre Edouard Fournier, Véronique Roux.

Centre CHU Reims, France: Alain Delmer, Chantal Himberlin, Brigitte Kolb, Quoc Hung Lé, Morgane Appriou, Joël Cousson, Pierre Nazeyrollas, Christophe Strady, Christophe de Champs, Véronique Vernet, Alain Delmer, Dominique Toubas.

Centre CHU Saint Etienne, France: Denis Guyotat, Christian Auboyer, Fabrice Zeni, Eric Alamartine, Pascal Cathebras, Frédéric Lucht, Alain Viallon, Adrien Melis, Alain Ros, Anne Carricajo, Camille Devanlay, Carine Labruyere, Catherine Vautrin, Céline Cazorla, Emmanuelle Tavernier, Florence Grattard, Gérald Aubert, Jerome Morel, Jérome Cornillon, Karima Abba, Pierre Flori, Roger Tran Manh Sung, Bruno Pozzetto.

Centre CHU Strasbourg, France: Francis Schneider, Yves Hansmann, Raoul Herbrecht, Julien Pottecher, Benoit Jaulhac, Yves Piémont, Valérie Lestcher.

Centre CHU Tours, France: Philippe Colombat, Delphine Senecal, Denis Garot, Dominique Perrottin, Jean-Marc Besnier, Alain Goudeau, Philippe Lanotte, Jacques Chandenier.

Centre coordinators

Marie Hélène Nicolas-Chanoine (APHP-Beaujon); Raymond Ruimy (APHP -Bichat); Alexandra Doloy (APHP -Cochin); Stéphane Bretagne (APHP -Henri Mondor); Florence Brossier, (APHP -Pitié-Salpêtrière); Valérie Lalande (APHP -Saint Antoine); Isabelle Casin (APHP -Saint Louis); Cécile Bébéar (Bordeaux); Geneviève Hery-Arnaud (Brest); Max Maurin (Grenoble); René Courcol (Lille); Marie-Cécile Ploy (Limoges); Monique Chomarat (Lyon); Michel Drancourt (Marseille); Christophe de Champs (Reims); Florence Grattard (Saint Etienne); Yves Piémont (Strasbourg); Philippe Lanotte (Tours).

Clinical research teams

Samia Baloul, Céline Corbel, Moufida Dabbech, Mabel Gaba, Elsa Jozefowicz , Magali Lafaye, Remi Rabeuf, Hasina Rabetrano, Kalaivani Veerabudun, Cédric Viallette.

Scientific Committee

Emmanuelle Cambau, Isabelle Durand-Zaleski, Stéphane Bretagne, Christian Brun-Buisson, Catherine Cordonnier, Xavier Duval, Stéphanie Herwegh, René Courcol, Sylvie Bastuji-Garin, Jean-Paul Stahl, Raoul Herbrecht, Laurence Delhaes, Karine Faure, Julien Pottecher.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

EC, RC, CC, and SB conceived the idea for the study. SBJ and IDZ conceive the methodology for the clinical trial and the economic evaluation, including the statistics. RC, SH and EC conducted the technical microbiological work in the 18 different hospitals. CC assisted in the design of the protocol and interpretation of results for the febrile neutropenia; CBB and JP did the same for the sepsis indication; XD for the suspicion of infective endocarditis. All authors contributed to the analysis of the data. EC, SBJ, IDZ wrote the drafts. All authors contributed to the revision of the paper drafts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest within the scope of this study.

Funding

The study was fund by the French Ministry of Health (Grant n°STIC IC0703; P070308 and IDRCB 2007-A01443-50). Clinical research was monitored by the Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) institution and particularly the Unité de Recherche Clinique (URC) Mondor. Data basis was collected and stored at URC Mondor. The trial protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Ile-de-France (CPP Ile de France 1 no. 0811715). Written informed consents were obtained for all patients and good practices in clinical research were monitored by the Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) institution.

Additional information

Members of The EVAMICA study team are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Take-home message:

Direct detection by PCR of bacterial and fungal DNA increases the number of patients with confirmed microbial aetiology of severe sepsis, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy can be given more rapidly. Molecular detection of pathogens was shown to be cost-effective when performed in addition to blood cultures in patients with severe sepsis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

134_2017_4766_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Numbers of patients with regard to the periods, the microbiological documentation and the appropriateness of the antimicrobial treatment 1 (DOCX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cambau, E., Durand-Zaleski, I., Bretagne, S. et al. Performance and economic evaluation of the molecular detection of pathogens for patients with severe infections: the EVAMICA open-label, cluster-randomised, interventional crossover trial. Intensive Care Med 43, 1613–1625 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4766-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4766-4