Abstract

Purpose

Physicians play an important role in strategies to control health care spending. Being aware of the cost of prescriptions is surely the first step to incorporating cost-consciousness into medical practice. The aim of this study was to evaluate current intensivists’ knowledge of the costs of common prescriptions and to identify factors influencing the accuracy of cost estimations.

Methods

Junior and senior physicians in 99 French intensive care units were asked, by questionnaire, to estimate the true hospital costs of 46 selected prescriptions commonly used in critical care practice.

Results

With an 83 % response rate, 1092 questionnaires were examined, completed by 575 (53 %) and 517 (47 %) junior and senior intensivists, respectively. Only 315 (29 %) of the overall estimates were within 50 % of the true cost. Response errors included a 14,756 ± 301 € underestimation, i.e., −58 ± 1 % of the total sum (25,595 €). High-cost drugs (>1000 €) were significantly (p < 0.001) the most underestimated prescriptions (−67 ± 1 %). Junior grade physicians underestimated more costs than senior physicians (p < 0.001). Using multivariate analysis, junior physicians [odds ratio (OR), 2.1; 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI), 1.43–3.08; p = 0.0002] and female gender (OR, 1.4; 95 % CI, 1.04–1.89; p = 0.02) were both independently associated with incorrect cost estimations.

Conclusions

ICU physicians have a poor awareness of prescriptions costs, especially with regards to high-cost drugs. Considerable emphasis and effort are still required to integrate the cost-containment problem into the daily prescriptions in ICUs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many Western countries, the economic imbalance of public health systems is directly linked to the uninterrupted increase in health care expenses [1]. Clinicians, responsible for the consumption of nearly all of the care and medical goods, play an important role in strategies for directing health care spending [2–4]. Previous studies have shown important cost savings through the application of rationalized prescriptions while maintaining equivalent heath care management [5–11]. In any health system, a medical cost-control strategy involves the optimization of health expenses through the promotion of medical care quality and the application of established care practices. In France, for example, replacing a global endowment health management system with an activity-based financing system rapidly compelled physicians to accept greater accountability in the cost-control problem [12]. Medical prescriptions are therefore meant to be more considered and more reasonable. More and more doctors feel that costs are an important consideration in the medical thought process that leads to prescribing decisions [13, 14].

Nowadays, incorporating cost-consciousness into our daily practice is unavoidable. Intensive care units (ICUs) represent a large portion of health care expenditures, estimated to reach up to 20 % of some hospital budgets [15]. Consequently, reducing costs in these units has become a priority [16]. Changing physicians’ attitudes towards cost control requires preliminary knowledge of prescription costs. Previous surveys, conducted in North America and Europe, have shown that doctors have a poor understanding of the costs of drugs, laboratory tests, and imaging modalities [17–23]. While several studies were aimed at optimizing ICU prescription strategies, only a few small studies performed over ten years ago investigated intensivists’ cost awareness [17, 19, 20].

The aim of the present work was to assess current intensivists’ knowledge of prescriptions costs in a national ICU study and to identify factors influencing the accuracy of cost estimations.

Materials and methods

Study design

A written questionnaire study was performed from May to December 2010. In each participating unit, every junior (residents and medical students) and senior (MD degree) intensive care physician was surveyed by a local correspondent. The characteristics of the participants (age, sex, level of training, financial training) and descriptions of the centers (medical/surgical ICU, academic/nonacademic hospital) were collected. Surveyed prescribers were anonymously asked to individually estimate the true costs of selected prescriptions.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire listed 46 prescriptions (medications and investigations) commonly used for diagnosis and treatment in ICU practice. These were gathered into four groups: drugs, blood products and derivatives, imaging modalities, and laboratory tests (Table 1). For each group, items were distributed in homogenous subgroups defined a priori (Table 1). The selected prescriptions were either the most frequent and/or expensive ones (annual amount) or regarded as essential to ICU practice. The total cost of the prescriptions was 25,595 €. True hospital costs were obtained using the average costs of drugs and blood products and derivatives in the Hospices Civils de Lyon (i.e., the University Teaching Hospital of Lyon, France), while the costs of the imaging modalities and laboratory tests were based on the French national averages. By the end of the study, a questionnaire with correct estimates was sent to each participant.

Typical clinical cases

To appreciate the value of cost awareness in the real world, we took into account two clinical situations observed daily in ICU practice: (1) septic shock due to community-acquired pneumonia (case 1); (2) hemorrhagic shock occurring under vitamin K antagonist (case 2). As reported in Table 1, we considered a 7-day ICU management associated with a number of prescriptions. The true costs, amounting in total to 2223 € for case 1 and 7238 € for case 2, were compared to estimated costs.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as number (percentage) and as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), as appropriate. The data analysis was performed as follows: calculation of response rates, description of physicians’ characteristics, evaluation of the accuracy of the estimates within margins of error defined a priori (±10, ±25, ±50, and >50 %), comparison of estimate deviations (in real and absolute values), and identification of factors influencing cost estimation accuracy. Accuracy was defined by estimates within 50 % of the true cost.

Univariate comparisons were performed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables, and a Chi-squared test for categorical variables, as appropriate. The independent contribution of physicians’ characteristics to incorrect estimations was tested by a logistic regression analysis. All variables with a p value less than 0.10 following univariate analysis were introduced into the model. Odds ratios (OR) were estimated with a 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI). Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc® 7.4.3.0 software (Medcalc, Mariakerke, Belgium). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

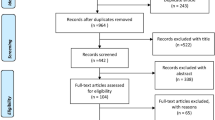

The response rate among the physicians of the 99 participating services was 83 %: 1092 questionnaires were completed from the 1315 surveys handed out. There was no significant difference between the response rates from academic (83 ± 21 %) and nonacademic (84 ± 21 %) hospitals (p = ns).

The characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 2. The majority of physicians were under 40 years old (79 %), male (sex ratio 1.5), and operating in medical or medical and surgical ICUs (83 %). As expected, the ratio junior/senior physicians was significantly higher (p < 0.01) in academic hospitals (3.7) when compared to nonacademic hospitals (0.3).

Concerning cost accuracy, most estimates were not within 50 % of the true cost for any prescription group (Table 3). Only 315 physicians (29 %) accurately estimated costs within 50 % of the true cost for the total amount (25,595 €). Response errors included an underestimation of 14,756 ± 301 €, i.e., −58 ± 1 % of the total sum. Absolute value deviations were 79 ± 1 % for drugs, 81 ± 2 % for blood products and derivatives, 73 ± 2 % for imaging modalities, and 73 ± 1 % for laboratory tests. As shown in Fig. 1a, drug costs were the most significantly (p < 0.001) underestimated (−64 ± 1 %), when compared to blood products and derivatives (−57 ± 2 %) or laboratory tests prescriptions (−36 ± 1 %). Imaging modality prescriptions were the only costs that were overestimated (7 ± 3 %). As shown in Fig. 1b, most prescription subgroups were underestimated. A clear trend in the overestimation of cheap prescriptions and the underestimation of expensive ones was observed. This was particularly true in drugs estimations (Table 4). For example, the drug subgroup “less than 10 €” was the only one commonly overestimated (961 ± 45 %). In contrast, “more than 1000 €” was the most underestimated drug subgroup (−67 ± 1 %), representing a considerable economic impact (−10,235 ± 196 € for a true cost of 15,358 € for this subgroup of prescriptions).

a Cost estimations according to level of training of the physicians. For most of the underestimated groups of prescriptions and for the total amount, estimations by senior grade physicians (green bar) were significantly more accurate than those of junior physicians (blue bar). *p < 0.05 versus “seniors”. b Cost estimations according to prescription subgroups. Correct estimations (green bar) were defined as being within 50 % of the true cost, overestimations (black bar) >50 % of the true cost, and underestimations (red bar) <−50 % of the true cost. The “<10 €” drugs subgroup (i.e., the cheapest one) was the only subgroup overestimated by more than 50 % of responders. The more expensive the other subgroups were, the more underestimated they were. 1 <10 € drugs, 2 10–100 € drugs, 3 100–1000 € drugs, 4 more than 1000 € drugs, 5 plasma, 6 red cells, 7 platelets, 8 blood derivatives, 9 basic radiology, 10 echo-Doppler, 11 computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging, 12 specialized radiology, 13 hematology, 14 biochemistry, 15 toxicology, 16 microbiology

Meaningful underestimations were also found in the two considered clinical situations. Using a ±50 % margin of error, our analysis indicated that 393 physicians (36 %) inaccurately estimated costs of prescriptions for case 1 (septic shock), 513 (47 %) for case 2 (hemorrhagic shock). Response errors of physicians averaged −173 ± 46 €, i.e., −8 ± 2 % of the true cost, for case 1, and −2423 ± 102 €, i.e., −33 ± 1 %, for case 2.

For the underestimated groups of prescriptions and for the total amount, the cost estimations of senior grade physicians were more accurate (p < 0.05) than those of the juniors (Fig. 1a). Age, sex, level of experience, hospital characteristics, and financial training significantly influenced the accuracy of cost estimations (Table 2). In multivariate analysis, junior physicians (OR, 2.1; 95 % CI, 1.43–3.08; p = 0.0002) and female gender (OR, 1.4; 95 % CI, 1.04–1.89; p = 0.02) were the only variables independently associated with incorrect cost estimations.

Discussion

The present study shows that, on a national level, intensivists have poor awareness of ICU costs. This knowledge deficit, particularly apparent among junior physicians, is dramatically illustrated in the lack of appreciation of the costs of the most expensive prescriptions.

The burden of the economic situation in health care demands the application of a medical cost-control strategy, urging physicians to provide cost-effective management without compromising quality of care. The goal of a tight cost-control management is obviously not to reduce the level of care but to optimize resources allocated for health, which are not unlimited. Respecting evidence-based medicine, physicians must now make choices when prescribing in order to give cost-effectiveness and optimal care quality [24, 25]. Because of the large portion of health care expenditure directly attributable to the ICUs, this urgent issue is particularly important in critical care medicine [26, 27]. Indeed, on a daily basis, intensivists are faced with new diagnostic tests, specialized disposables, or expensive drugs, which represent a significant part of the growing expenditures of health care [28, 29]. Individually, ICU prescribers play a key role in the critical care cost-containment problem: their medical responsibility is especially linked to the economic impact of the care they provide. Making prescribers responsible requires in-depth changes in prescribing patterns and in the physician’s attitudes towards cost awareness [3, 13]. Being aware of prescription costs is surely the first step in incorporating cost-consciousness into medical prescribing decisions [30–32].

Here, we carried out the largest study to date concerning cost awareness among physicians. Previous studies were mainly conducted in North America and Europe in the 1990s and 2000s and evaluated drug cost awareness among general practitioners, emergency physicians, or anesthetists [17–23]. Inadequate knowledge of costs by physicians was consistently found in these surveys [17–23]. Despite the growing need of medical responsibilization in cost control, cost awareness has not apparently improved over time. As demonstrated by our results, cost accuracy remains largely insufficient, even if we choose a quite large margin of error (±50 %) to define “correct” estimations. We also found that estimations by senior grade physicians were more accurate than their junior colleagues. This result was in contrast with previous reports that showed that the level of experience had no influence on cost awareness [20–22]. This specific influencing factor has probably been identified in our study owing to the high number of responders. Impact of professional experience on cost-consciousness is encouraging, suggesting that physicians may gradually incorporate economic considerations into their medical practices. We also found that cost estimations by female intensivists were less accurate than those of men. To the best of our knowledge, physician gender influence has never previously been documented. Our results also show that physicians have a tendency to overestimate cheap prescriptions and to underestimate expensive ones, a point consistently reported in the literature for decades [19, 21, 23]. In our study, the most expensive subgroup of prescriptions (“more than 1000 €” drugs) was the most underestimated, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the underestimation of the global amount. The presence in our questionnaire of five prescriptions exceeding 1000 € might partially explain the worrying estimates we observed. Be that as it may, high-cost drugs are now accounting for a large part of ICU budgets, and focus, more than ignorance, is required to deal with this growing major concern.

One limitation of our study might be that the inaccuracy of the estimations has not been weighted for the frequency of prescriptions or global health care management; both of these parameters are necessary to analyze the economic impact. However, through the two typical clinical cases we chose, our results allow one to indirectly appreciate the value of estimated costs in the real world. The quite small differences we observed in cost estimation per patient must be read in conjunction with the number of admissions of these patients in ICUs. For example, on the basis of a recent epidemiological study of septic shock in France [33], finding more than 50 patients yearly admitted for septic shock in each center, our results would be relevant with an approximately 10,000 € annual underestimation per ICU. Concerning hemorrhagic shock, such a dramatic amount would be reached with only four underestimations of this clinical situation. Some other limitations must be acknowledged. First, inter-hospital variability of true costs, particularly for drugs and imaging modalities, remains a reality in France, as elsewhere, that might have influenced physicians’ estimations. However, these variations can be considered as negligible when compared to the major response errors observed, especially for high-cost prescriptions. Second, we may speculate that responders were probably physicians who were the most concerned by the cost-containment issue. Nevertheless, this potential bias was substantially limited by the high response rate. Third, we have no data on how survey responders were informed on costs in each ICU; yet this factor may have affected cost estimates. Finally, the cost awareness of French physicians might have been influenced by the activity-based financing system; any transposition of our results to another health system remains uncertain.

Improving physicians’ cost awareness remains a challenge. Two important approaches can be considered: provide better information and reinforce training. Doctors appear to be predisposed to practice cost-effective medicine, but complain about problems obtaining information about costs [13]. Interventions are needed to provide reliable, easily accessible, and up-to-date cost information in everyday practice. In view of the risks of biased or inaccurate information, physicians appear to prefer academic sources or direct communication with hospital administration [21]. Another information vector could be heath information technology, increasingly used in ICUs. Associated with evidence-based decision support, computerized prescribing software providing fee data has demonstrated an efficacy to achieve cost savings [34–36]. In our study, none of the participating ICUs had adopted such a promising tool, illustrating a dramatic underutilization of cost report software. In addition, it appears essential to reinforce medical education about costs and health care management. In our study, less than 2 % of physicians had an econometrics qualification. It would be desirable for medical educators to offer more courses (in medical school, during residency, and in continuing medical education) dedicated to global health care management and general cost education [37, 38]. Professional cost-consciousness projects, which give a framework for teaching and practicing cost awareness in ICU, could also be an interesting approach [39]. As our results highlight, educational programs dedicated to cost awareness should be particularly targeted at young physicians, who are responsible for a high number of avoidable prescriptions [40, 41]. Further research should also focus on the long-term impact of cost-awareness educational programs and easier access to cost information resources.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the alarmingly poor awareness of intensivists to costs, especially with regards to high-cost prescriptions. Considerable focus and efforts are still required to strengthen physicians’ responsibilities and to incorporate cost control in daily ICU practice.

References

OECD (2013) Public spending on health and long-term care: a new set of projections. Main Paper, Economic Policy Paper no. 6, 2013. http://www.oecd.org/eco/growth/public-spending-on-health-and-long-term-care.htm. Accessed 29 April 2015

Dresnick S, Roth W, Linn B, Pratt T, Blum A (1979) The physician’s role in the cost-containment problem. JAMA 241:1606–1609

Cooke M (2010) Cost-consciousness in patient care—what is medical education’s responsibility? N Engl J Med 362:1253–1255

Brook RH (2010) What if physicians actually had to control medical costs? JAMA 304:1489–1490

Erban SB, Kinman JL, Schwartz JS (1989) Routine use of the prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. JAMA 262:2428–2432

Talmor D, Shapiro N, Greenberg D, Stone PW, Neumann PJ (2006) When is critical care medicine cost-effective? A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness literature. Crit Care Med 34:2738–2747

Talmor D, Greenberg D, Howell MD, Lisbon A, Novack V, Shapiro N (2008) The costs and cost-effectiveness of an integrated sepsis treatment protocol. Crit Care Med 36:1168–1174

Prat G, Lefèvre M, Nowak E, Tonnelier JM, Renault A, L’Her E, Boles JM (2009) Impact of guidelines to improve appropriateness of laboratory tests and chest radiographs. Intensive Care Med 35:1047–1053

Heljblum G, Chalumeau-Lemoine L, Loos V, Boëlle PY, Salomon L, Simon T, Vibert JF, Guidet B (2009) Comparison of routine and on-demand prescription of chest radiographs in mechanically ventilated adults: a multicentre, cluster-randomised, two-period crossover study. Lancet 374:1656–1658

Heene S, Jacobs F, Vincent JL (2012) Antibiotic strategies in severe nosocomial sepsis: why do we not de-escalate more often? Crit Care Med 40:1404–1409

Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, Concepcion M, Hernandez-Gea V, Aracil C, Graupera I, Poca M, Alvarez-Urturi C, Gordillo J, Guarner-Argente C, Santalo M, Muniz E, Guarner C (2013) Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 368:11–21

Crainich D, Leleu H, Mauleon A (2011) Hospital’s activity-based financing system and manager: physician interaction. Eur J Health Econ 12:417–427

Reichert S, Simon T, Halm EA (2000) Physicians attitudes about prescribing and knowledge of the costs of common medications. Arch Intern Med 160:2799–2803

Bovier PA, Martin DP, Perneger TV (2005) Cost-consciousness among Swiss doctors: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 5:72

Chalfin DB (1995) Cost-effectiveness analysis in health care. Hosp Cost Manag Account 7:1–8

Kahn JM, Nagus DC (2006) Reducing the cost of critical care: new challenges, new solutions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174:1167–1170

Fairbrass MJ, Chaffe AG (1988) Staff awareness of cost of anaesthetic drugs, fluids and disposables. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 296:1040

Ryan M, Yule B, Bond C, Taylor R (1990) Scottish general practitioner attitudes and knowledge in respect to prescribing costs. BMJ 300:1316–1318

Bailey CR, Ruggier R, Cashman JN (1993) Anaesthesia: cheap at twice the price? Staff awareness, cost comparisons and recommendations for economic savings. Anaesthesia 49:906–909

Conti G, Dell’Utri D, Pelaia P, Rosa G, Cogliati AA, Gasparetto A (1998) Do we know the costs of what we prescribe? A study on awareness of the cost of drugs and devices among ICU staff. Intensive Care Med 24:1194–1198

Allan M, Lexchin J, Wiebe N (2007) Physician awareness of drug cost: a systematic review. PLoS Med 4:1486–1496

Schilling U (2009) Cost awareness among Swedish physicians working at the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 16:131–134

Hernu R, Cour M, Causse G, Robert D, Argaud L (2013) Cost-awareness at emergencies: multicentric survey among prescribers. Presse Med 69:126–131

Noseworthy TW, Konopad E, Shustack A, Johnston R, Grace M (1996) Cost accounting of adult intensive care: methods and human and capital inputs. Crit Care Med 24:1168–1172

Garland A, Shaman Z, Baron J, Connors AF (2006) Physician-attributable differences in intensive care unit costs: a single-center study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174:1206–1210

Halpern NA, Pastores SM, Greenstein RJ (2004) Critical care medicine in the United States 1958–2000: an analysis of bed numbers, use, and costs. Crit Care Med 32:1254–1259

Moerer O, Plock E, Mgbor U, Schmid A, Schneider H, Wischnewsky MB, Buchardi H (2007) A German national prevalence study on the cost of intensive care: an evaluation from 51 intensive care units. Crit Care 11:R69

Blumenthal D (2001) Controlling health care expenditures. N Engl J Med 344:766–769

Jegers M, Edbrooke DL, Hibbert CL, Chalfin DB, Burchardi H (2002) Definitions and methods of cost assessment: an intensivist’s guide. ESICM section on health research and outcome working group on cost effectiveness. Intensive Care Med 28:680–685

Hart J, Salman H, Bergman M, Neuman V, Rudniki C, Matalon A, Djaldetti M (1997) Do drug costs affect physicians prescription decisions? J Intern Med 241:415–420

Shrank WH, Joseph GJ, Choudhry NK, Young HN, Ettner SL, Glassman P, Asch SM, Kravitz RL (2006) Physicians perceptions of relevant prescription drug costs: do costs the individual patient or the population matter most? Am J Manag Care 12:545–551

Polinski JM, Maclure M, Marshall B, Cassels A, Agnew-Blais J, Patrick AR, Schneeweiss S (2008) Does knowledge of medication prices predict physicians support for cost effective prescribing policies? Can J Clin Pharmacol 15:286–294

Quenot JP, Binquet C, Kara F, Martinet O, Ganster F, Navellou JC, Castelain V, Barraud D, Cousson J, Louis G, Perez P, Kuteifan K, Noirot A, Badie J, Mezher C, Lessire H, Pavon A (2013) The epidemiology of septic shock in French intensive care units: the prospective multicenter cohort EPISS study. Crit Care 17:R65

Mc Mullin ST, Lonergan TP, Rynearson CS (2005) Twelve-month drug cost savings related to use of an electronic prescribing system with integrated decision support in primary care. J Manag Care Pharm 11:322–332

Tseng CW, Brokk RH, Alexander GC, Hixon AL, Keeler EB, Mangione CM, Chen R, Jackson EA, Dudley RA (2010) Health information technology and physicians knowledge of drug costs. Am J Manag Care 16:105–110

Feldman LS, Shihab HM, Thiemann D, Yeh HC, Ardolino M, Mandell S, Brotman DJ (2013) Impact of providing fee data on laboratory test ordering: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 173:903–908

Agrawal JR, Huebner J, Hedgecock J, Sehgal AR, Jung P, Simon SR (2005) Medical students’ knowledge of the US healthcare system and their preferences for curricular change: a national survey. Acad Med 80:484–488

Frazier LM, Brown JT, Divine GW, Fleming GR, Philips NM, Siegal WC, Khayrallah MA (1991) Can physician education lower the cost of prescription drugs. A prospective, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 115:116–121

Anstey MH, Weinburger SE, Roberts DH (2014) Teaching and practicing cost-awareness in the intensive care unit: a TARGET to aim for. J Crit Care 29:107–111

Miyakis S, Karamanof G, Liontos M, Mountokalakis TD (2006) Factors contributing to inappropriate ordering of tests in an academic medical department and the effect of an educational feedback strategy. Postgrad Med 82:823–829

Moriates C, Soni K, Lai A, Ranji S (2013) The value in the evidence: teaching residents to choose wisely. JAMA Intern Med 173:308–310

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of our institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. For this type of study formal consent was not required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

On behalf of the “Costs in French ICU” Study Group.

The list of co-investigators appears in the "Appendix" section.

Take-home message: ICU physicians have a poor awareness of prescriptions costs, especially with regards to high-cost drugs. Considerable emphasis and effort are still required to integrate the cost-containment problem into the daily prescriptions in ICUs.

Appendix: Co-investigators

Appendix: Co-investigators

Members of the “Costs in French ICU” Study Group (CHU = university hospital, CH = non-university hospital):

CH Alençon: A. Merouani; CHU Amiens: J. Maizel; CHU Angers: L. Masson, A. Mercat; CH Annecy: D. Bougon; CH Annonay: V. Cadiergue; CH Argenteuil: H. Mentec; CH Beauvais: A.M. Guerin; CH Belfort-Montbéliard: M. Feissel; CHU Boulogne-Billancourt: C. Charron; CH Boulogne-sur-mer: R. Pordes; CH Bourg-en-Bresse: N. Sedillot; CHU Brest: J.M. Boles, G. Prat; CH Briançon: B. Langevin; CH Brive-la-Gaillarde: M. Mattei; CHU Caen: M. Jokic; CH Chalon-sur-Saône: J.M. Doise; CH Chambéry: M. Badet, J.M. Thouret; CH Charleville-Mezières: A. Bertrand; CHU G. Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand: A. Lautrette, N. Gazuy, B. Souweine; Hôpital Privé J. Perrin, Clermont-Ferrand: B. Nougarede; CHU Colombes: J. Messika; CH Dax: A. Haffiane; CHU Dijon: M. Freysz, P. Obbée, J.P. Quenot; CH Douai: C. Boulle; CH Draguignan: N. Bele; CHU Garches: J. Aboab; CHU A. Michalon, Grenoble: A.S. Lucas, C. Schwebel, J.F. Timsit; CH Haguenau: F. Kara; CHU R. Salengro, Lille: M. Jourdain; CHU Croix-Rousse, Lyon: G. Bourdin, S. Duperret, C. Guérin, J.C. Richard; CHU E. Herriot, Lyon: T. Baudry, J. Crozon, E. Faucher, B. Floccard, E. Hautin, J. Illinger, J.M. Robert, M. Simon; CHU HFME, Lyon: F. Cour-Andlauer; CHU L. Pradel, Lyon: G. Keller; CHU Lyon Sud: J. Bohé; Hôpital Privé Saint-Joseph Saint-Luc, Lyon: M. Fontaine, S. Rosselli; Hôpital Privé Tonkin, Lyon: F. Salord; CH Mâcon: D. Debatty; CH Melun: M. Monchi; CHU Marseille Nord: L. Papazian, A. Roch; CHU Timone, Marseille: M. Gainnier; CHU Metz: G. Louis; CH Montélimar: O. Millet; CHU Lapeyronnie, Montpellier: M. Conseil, K. Klouche, K. Lakhal; CHU Guide Chauliac, Montpellier: O. Jonquet, P.L. Massanet; CHU Brabois, Nancy: B. Levy, J.F. Perrier; CHU Central, Nancy: P.E. Bollaert; CHU Nantes: C. Bretonniere; CHU l’Archet, Nice: G. Bernardin, J. Dellamonica, H. Hyvernat; CHU Saint-Roch, Nice: J.C. Orban; CHU, Nîmes: L. Elotmani, J.Y. Lefrant; CH Nouméa: H. Le Coq Saint-Gilles; CHU Cochin, Paris: J.P. Mira; CHU Kremlin-Bicêtre, Paris: N. Anguel, C. Richard; CHU Lariboisière, Paris: B. Megarbane; CHU La Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris: A. Duguet; CH G. Pompidou: D. Journois; CHU Saint-Louis, Paris: E. Azoulay; CHU Saint-Joseph, Paris: M. Garrouste-Orgeas, S. Hamada; CH Pau: P. Badia; CH Papeete: E. Bonnieux; CH Perpignan: O. De Matteis; CHU Poitiers: F. Petitpas, A. Veinstein; CH Pontoise: E. Boulet; CH La Rochelle: A. Herbland; CH La Roche-sur-Yon: I. Vinatier; CHU Rouen: D. Carpentier, C. Girault; CH Saint-Denis, La Réunion: A. Roussiaux, J. Sudrial; CH Saint-Dizier: S. Wuilbercq; CH Saint-Pierre, La Réunion: A. Winer; CH Toulon: J. Durand-Gasselin; CHU Rennes: A. Gros; CH Roanne: P. Beuret; CHU Saint-Étienne: C. Auboyer, L. Burnol, M. Darmon, E. Diconne, F. Zéni; CH Saint-Malo: J.P. Gouello; CH Saint-Quentin: B. Manoury; CHU Tours: S. Cantagrel; CH Valence: Q. Blanc; CH Versailles: S. Legriel; CH Villefranche-sur-Saône: K. Chaulier.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernu, R., Cour, M., de la Salle, S. et al. Cost awareness of physicians in intensive care units: a multicentric national study. Intensive Care Med 41, 1402–1410 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3859-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3859-1