Abstract

Background

Cognitive difficulties are common in people with severe mental disorders (SMDs) and various measures of cognition are of proven validity. However, there is a lack of systematic evidence regarding the psychometric properties of these measures in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Objective

To systematically review the psychometric properties of cognitive measures validated in people with SMDs in LMICs.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature by searching from four electronic databases. Two authors independently screened studies for their eligibility. Measurement properties of measures in all included studies were extracted. All eligible measures were assessed against criteria set for clinical and research recommendations. Results are summarized narratively and measures were grouped by measurement type and population.

Results

We identified 23 unique measures from 28 studies. None of these was from low-income settings. Seventeen of the measures were performance-based. The majority (n = 16/23) of the measures were validated in people with schizophrenia. The most commonly reported measurement properties were: known group, convergent, and divergent validity (n = 25/28). For most psychometric property, studies of methodological qualities were found to be doubtful. Among measures evaluated in people with schizophrenia, Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia, Cognitive Assessment Interview, MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, and CogState Schizophrenia Battery were with the highest scores for clinical and research recommendation.

Conclusions

Studies included in our review provide only limited quality evidence and future studies should consider adapting and validating measures using stronger designs and methods. Nonetheless, validated assessments of cognition could help in the management and allocating therapy in people with SMDs in LMICs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe mental disorders (SMDs) are defined as having a non-organic psychosis with long illness duration and severe functional impairment [1]. SMDs include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder with psychotic features. Despite their relatively low prevalence, these disorders are among the leading causes for Years Lived with Disability (YLD) [2]. Research shows that people with SMDs have significantly more cognitive difficulties compared to healthy controls [3,4,5,6,7]. In support of this, a recent systematic review showed that cognitive symptoms in people with schizophrenia (PWS) had heterogenous trajectories [8].

Cognition is a term referring to thinking skills including acquiring and retaining knowledge, processing information, and reasoning. Cognitive function includes intellectual abilities such as perception, reasoning, and remembering. Impairment in those functions (i.e., memory, judgment, and comprehension) is referred to as cognitive impairment [9]. PWS tend to have greater cognitive impairment compared to people with bipolar disorder (PWBD) and people with depression (PWD) [10,11,12,13].

Even though SMDs share nearly similar domains of cognitive impairment, the impairment in PWS is more global compared to the impairment in PWBD and PWD. Both PWS and PWBD show impairment in the domains of attention, verbal learning, and executive function [14, 15]. Whereas, domains of processing speed, working memory, verbal and visual learning, and reasoning are impaired in PWS and PWD [14, 16]. In addition to the above domains, PWS have more prominent impairment in the domain of social cognition [14], this may be used to differentiate PWS from PWBD and PWD.

Cognitive impairment in people with SMDs is associated with poor functional and clinical outcomes [17,18,19,20,21]. A recent study also showed that cognition worsens gradually if no intervention is provided [22]. Measuring cognition of people with SMDs with robust instruments is important, since measurement and assessment is the first step to intervention. For this purpose, several measures of cognition have been developed and validated in people with SMDs. Although several measures exist, most of these have been developed in Western countries and not always adapted well for use in low-income settings [23,24,25,26,27,28]. Norms for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) also do not always exist, making the use and interpretation of these measures complex. In addition, it is not clear which measures would be better candidates for adaptation to low-income setting, since there is no previously synthesized report about the measurement properties of measures adapted in LMICs. Furthermore, most cognitive measures require literacy to respond to the items. Therefore, separate review of validation studies conducted in LMICs can show readers which measure is more appropriate for adaptation in countries with low literacy rate. Finally, multiple languages are spoken in most LMICs as a result, and a separate review of validation studies conducted in LMICs may show readers which measure is adapted across different LMICs speaking different languages.

Although there are numerous studies on the validation of cognitive measures in people with SMDs, only one systematic review has addressed this [29], and there is no previous systematic review focusing on this issue in LMICs. This review is important, because it can help researchers and clinicians to choose the most appropriate measure for their context. As a result, this systematic review is aimed to fill this gap by reviewing the psychometric properties of cognitive measures adapted or developed and validated among people with SMDs in LMICs.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline to conduct and report this systematic review [30]. We registered the protocol on Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) before we started the search (registration number: CRD42019136099).

Databases searched

PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Global Index Medicus, and African Journals Online (AJOL) were searched from the date of inception of the databases until June 07, 2019. Google Scholar was used for forward and backward-searching. We conducted backward-searching on 3rd September 2019 and forward-searching on 29th September 2019.

Search strategy

We used free terms and controlled vocabulary terms for four keywords: SMDs, cognition, psychometric properties, and LMICs. We combined these four keywords with the Boolean term “AND”. For the complete search strategy, see online resource 1. To increase our chance of capturing all measures validated for the assessment of cognition in people with SMDs, we conducted a forward and backward search. In addition to our registered protocol, we consulted experts in the area by emailing the final list of measures identified for potentially missed measures.

Eligibility criteria

This review considered studies aimed at developing/adapting and validating a cognitive measure in people with SMDs aged 18 years and older in LMICs. Diagnoses of the disorders needed to be confirmed using either Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM) [31], International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [32], or other recognized diagnostic criteria. For this study, SMDs included schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depressive disorders. We chose these three groups of disorders, because cognitive impairment is prominent. We excluded normative studies and adaptation studies involving only healthy participants. Although a normative study is an important step in the adaptation of measures, our aim was to focus on evaluating measures validated in people with SMDs.

We included any measure which was used to assess at least one domain of cognition. Both performance-based (instruments that evaluate behavior on a task or performance) and interview-based (instruments in which the examiner scores the performance through clinical interviews) measures were included.

In this review, a validation study was operationally defined as any study conducted with the aim of evaluating the psychometric properties of a measure, i.e., a study with the main objective of reporting different dimensions of reliability and validity. We also included studies which reported the process of adaptation or development of a measure in people with SMDs without reporting psychometric properties of those measures. Studies only from LMICs were included in this review. We used the World Bank list of economic status of countries during the 2018/2019 financial year as a reference for categorizing countries. Only studies published in English with no restriction in study design were included in the review.

Full-text identification process

We merged articles found from the databases and removed duplicates. Two of the authors (YG, AD) independently screened each article for eligibility using their title and abstract, followed by full-text screening. Disagreements between the two screeners were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

The first author (YG) extracted data from the included articles using data extraction tool developed a priori, and another author (AD) checked all the extracted data for correctness of the extraction. The extraction tool was developed in consultation with the senior authors, referring to previous published systematic reviews, and the requirements for quality assessment followed by piloting it on two articles (the data extraction template is in online resource 2). The core components of the data extraction tool were:

-

Authors’ name and affiliation, date of publication, and country

-

Study design

-

Type of the study (development, adaptation, validation)

-

Mode of administration (interview-based vs performance-based)

-

Total number of participants in each group (control vs patients)

-

Sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, educational status, and language)

-

Duration to administer the tool

-

Specific cognitive domains addressed and the number of items of the measure and the domains/sub-tests

-

Psychometric properties reported, method of analysis, and findings

-

Elements of the quality assessment tool (described in detail on the quality assessment section below)

Risk of bias/quality assessment

YG and AD independently assessed the risk of bias of individual studies using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklist [33]. Any disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion. There were no disagreements beyond the consensus agreement between the two screeners. Unlike the registered protocol, we used the updated version of COSMIN checklist, in conducting this review.

COSMIN has a total of 10 boxes for 10 different psychometric properties (each box has 3–35 items). Four dimensions of scoring options are available for each item (i.e., very good, adequate, doubtful, and inadequate). A summary of quality per measurement property is given for each study by taking the worst result for each criterion (for each measurement property addressed) [36]. Since the studies included were not homogenous, we were not able to conduct an assessment of publication bias.

Criteria used to rank order the measures

In addition to our registered protocol, we evaluated and ranked cognitive measures validated in PWS using five criteria that we developed by adapting from previous reviews [37,38,39,40,41]. Our main reason for the rank ordering the measures is to recommend better measures for adaptation in other settings (it is not for quality assessment). The criteria used to rank the measures were:

-

1.

The number of studies that adapted/validated the measure: one point was given to each measure by counting the number of studies which reported information about the specific measure. According to this criterion, higher score was given to a measure adapted by many studies.

-

2.

Year of publication of studies adapted/validated the measure: in addition to number of studies, year of publication was considered to reduce the risk of recommending a measure which was adapted by many studies, just because it was developed earlier than others. A score of 5 was given for studies published in 2015 and after, while a score of one was given for studies published before 1980. For measures evaluated in more than one studies, the average of the publication year scores was taken.

-

3.

The number of domains the measure addressed: we scored this by counting the number of specific domains that the measure consisted. A single score was given by counting the number of domains that the measure holds from list of domains thought to be impaired in PWS as reported in the systematic review of Nuechterlein et al. [14].

-

4.

Duration to administer: we scored from one to three inversely, i.e., three for brief measures taking 30 min or less, two for measures which take between 30 and 60 min, and one for measures which take more than 60 min to administer.

-

5.

The number of psychometric properties addressed and findings: we added this criterion, since we wanted to consider the number of psychometric properties evaluated for the measure and findings reported. For this criterion, a scale from one to eight was used, where the maximum score was given if five or more measurement properties from COSMIN’s list were evaluated and reported excellent findings and the least score was given if less than two measurement properties were evaluated with less than excellent findings of any of the properties. We have not considered the COSMIN quality rating in this criterion, we only considered the number of measurement properties evaluated from COSMIN’s list and the findings reported. According to this criterion, a better measure is a measure on which many measurement properties have been evaluated and all had been scored excellent findings.

If the necessary information was not contained in the studies included, we gave a score of zero (not reported). The overall ranking of the measures was based on the total sum of scores according to the above five criteria. The highest total possible score is 28 with higher scores indicating a better measure for the recommendation.

Data synthesis

We used a narrative synthesis to report the findings. For each identified measure, we reported psychometric properties, duration to administer, and other important outcome points that we extracted [e.g., population on which the measure was evaluated, type of the measure (performance- or interview-based), cognitive domains, number of items, etc.]. We also reported the methodological qualities of each study for the specific measurement properties reported.

In addition to our registered protocol, we summarized and synthesized findings. Since the purpose of summarizing was for the aim of general tool selection, we used the updated criteria for good measurement properties in COSMIN systematic review for patient report outcome measurement manual version 1 released in February 2018 [33]. With regards to internal consistency, we graded a Cronbach’s α of ≥ 0.7 as excellent, and < 0.7 as satisfactory. For test–retest assessment, intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) ≥ 0.7 was considered as high, while < 0.7 was considered as poor. For tests with Pearson correlation (r) (for test–retest reliability, convergent, or concurrent validity), we used Cohen’s classification and assigned ≥ 0.5 as large, r between 0.3 and 0.49 as medium, and between 0.1 and 0.29 as small. Furthermore, we used the COSMIN criteria for summarizing evidence and grade the quality of evidence per measurement properties for measures validated in PWS in more than one study [33].

We reported results for performance-based and interview-based measures separately. We also compared measures validated in PWS with measures validated in PWD and PWBD. It was not possible to conduct meta-analysis and meta-regression because of heterogeneous findings in terms of the measures included and measurement properties reported.

Results

Study characteristics

The search strategy yielded a total of 6091 articles. Title and abstract screening yielded 67 articles. Full-text screening, forward and backward-searching resulted in 27 articles. One article is added later through peer recommendation and the total articles included in this review were 28. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of article identification. A list of excluded articles with the reason for their exclusion is provided in the online resource 3.

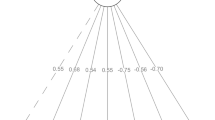

The 28 studies included in the review evaluated psychometric properties of 23 cognitive measures in people with SMDs from 12 LMICs. Most of these studies were from Brazil (n = 7/12) [42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. No study was conducted in low-income countries and only three studies were conducted in lower-middle-income countries [49,50,51] (Fig. 2).

About two-third of the studies (n = 18/28) were conducted either in PWS or people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (PWSSD) with healthy controls (n = 13/18) [42, 43, 45, 46, 49, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] or without healthy controls (n = 5/18) [47, 50, 51, 59, 60,]. Three studies each were conducted in PWD [44, 62, 63] and PWBD [48, 64, 65] with healthy controls, while those remaining (n = 4/28) were conducted in mixed populations [66,67,68,69]. A total of 6396 participants (2196 clinical samples and 4200 healthy controls) were included in the main studies of this review. The sample size of PWS/PWSSD in the included studies ranged from 15 to 230 (with a median of 50) for the main studies and 15 to 188 for test–retest reliability. The sample size for healthy controls ranged from 15 to 1757 (with a median of 77) for the main studies and 15 to 84 for test–retest reliability studies. The mean age of PWS/PWSSD participants was 35.2 years. Most studies (n = 15/21) had more male participants. On average, PWS/PWSSD had 10.7 years of education. Table 1 describes the participants' characteristics.

Description of the measures

Twenty-three cognitive measures were identified from the 28 studies included. Of these, 15 were evaluated in PWSSD, three in PWD, one in PWBD, and one in PWS and PWD, while three measures were evaluated in a mixed population. The identified measures addressed either single domain of cognition or as many as seven domains, with duration to administer ranging from 10 to 90 min.

Of the measures identified, 17 were performance-based and 12 were evaluated in PWSSD, one each in PWD; and in PWS and PWD, and three in a mixed population. About half of these measures (n = 8/17) addressed only neurocognition domains and six addressed social cognition, while three included domains of both neurocognition and social cognition. About two-third of the measures were batteries (n = 11/17), while six were single-domain tests.

Six of the 23 measures identified were interview-based. Out of these, three were evaluated in PWSSD, two in PWD, and one in PWBD. Except for one, all these measures addressed neurocognitive domains only (n = 5/6). See Table 2 for detailed description of the measures.

Psychometric properties evaluated

These are summarized in Table 3. The most commonly studied psychometric property was hypothesis testing, including convergent, concurrent, and known group validity (evaluated in 25 studies), followed by internal consistency reliability (evaluated in 20 studies), and cross-cultural validity (evaluated in 15 studies). Test–retest reliability was conducted in 14 studies, whereas structural validity was conducted in 11 studies. The least reported measurement property was content validity (n = 3/28), followed by criterion validity (n = 4/28). None of the included studies evaluated responsiveness to change or measurement error. Very few (n = 6/28) studies reported other measurement properties, such as face validity (n = 1/28), learning effects (n = 1/28), tolerability/feasibility (n = 2/28), floor and ceiling effects (n = 2/28), comparison of measures (n = 1/28), or cross-cultural comparisons (n = 1/28).

It was not possible to pool the findings of the psychometric properties reported because of heterogeneity in the measures used, psychometric properties reported, and populations studied. We therefore summarized them in Table 3 and provided a narrative synthesis.

Almost all of the studies reported excellent internal consistency (n = 18/20), and most studies reported high test–retest reliability (n = 11/14). Only one-third of the studies reported good concurrent validity (n = 4/14), whereas good convergent validity was reported by most studies (n = 11/15). All of the studies (n = 21) which evaluated known group validity reported good ability to discriminate different clinical samples and healthy controls. Likewise, appropriate content validity (n = 4), excellent criterion validity (n = 4), high tolerability/feasibility (n = 2), good face validity (n = 1), minimal floor and ceiling effect (n = 2), and no learning effect (n = 1) were also reported.

Of the studies which evaluated performance-based measures, the majority reported excellent internal consistency (n = 8/12), high test–retest reliability (8/11), and good concurrent validity (n = 4/8). Good convergent validity was reported in two-third of the studies (n = 6/9). Three studies assessed structural validity and two of them reported one-factor structure and the other one reported a two-factor structure. Two studies evaluated criterion validity and reported excellent sensitivity and specificity. Nine different studies evaluated cross-cultural validly and yielded nine different versions of the measures.

Of the studies which evaluated interview-based measures, all reported excellent internal consistency (n = 8/8), high test–retest reliability (3/3), and good convergent validity (n = 5/6). None of the included studies reported good concurrent validly, whereas two-thirds of the studies reported moderate concurrent validity (n = 4/6). Seven studies assessed structural validity and five of them reported one factor, one study reported three factors, and another one reported six factors. Two studies evaluated criterion validity and reported excellent sensitivity and specificity. Six different studies evaluated cross-cultural validly and yielded six different versions of the measures. Two studies evaluated feasibility/tolerability of measures and found that both measures were feasible/tolerable for the respondents (less than 1% of missing values were reported). See Table 3 for details.

Summary of evidence per measure

Three studies [47, 61, 62] reported more than one measure, while six measures were described by more than one study. In Table 4, we summarized the psychometric properties of measures reported in more than one study in PWS. For detailed psychometric properties of measures reported in other population and in PWS in only one study, please see Table 3.

Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS): this performance-based measure was evaluated in five studies [42, 43, 51, 56, 60]. BACS has six sub-tests which address seven domains of cognition, and on average, it takes 37.4 min to administer it in PWS (Table 2).

High-quality evidence was reported for internal consistency (with positive rating from four studies), and hypothesis testing (with mixed result with most reporting good concurrent, convergent, and known group validity from four studies). While moderate-quality evidence was reported for structural validity (with one-factor structure from two studies) and cross-cultural validity (yielded Persian, Brazilian, Indonesian, and Malay version). However, low-quality evidence was reported for test–retest reliability (with positive rating from three studies) and criterion validity (with positive rating from one study). Other than the COSMIN list of measurement properties, minimal ceiling and floor effect were reported in one study (Table 4).

Frontal assessment battery (FAB): Two studies [54, 69] evaluated this performance-based measure. FAB has six sub-tests each to be scored in a Likert scale from 0 to 3 with a total score of 0 to 18. A higher score reflects better performance. It takes only 10 min for administration, but it assesses only one domain (i.e., executive function) (Table 2).

High-quality evidence were reported for internal consistency (with negative rating from two studies), and hypothesis testing (with positive rating for good concurrent, convergent, and known group validity from two studies). Whereas moderate-quality evidence was reported for test–retest reliability (with intermediate rating from two studies). However, low-quality evidence was reported for cross-cultural validity [54]. Other than the COSMIN list of measurement properties, very high inter-rater reliability was reported in one study (Table 4).

Hinting task: Two studies [48, 61] addressed this performance-based measure of theory of mind. The Hinting task comprised 10 short sketches/stories which focused on assessing the person’s ability to describe the intention of the person from the stories presented (Table 2).

Cross-cultural validity (n = 1/2) and comparison with other tests (n = 1/2) were evaluated for this measure. The cross-cultural validity of the Hinting task resulted in the Brazilian version which was rated as low-quality evidence, while it was found to be the least difficult measure in detecting theory of mind compared with Reading the Mind in the Eye Tests (RMET) and Faux pas test (Table 4).

Clinical and research usefulness evaluation

We ranked measures evaluated in PWS using five criteria described in detail in the section “Criteria used to rank order the measures”. Summing the scores for each criterion, BACS ranked first, Cognitive Assessment Interview (CAI) ranked second, and MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) and CogState Schizophrenia Battery (CSB) ranked third. When looked at performance-based and interview-based measures separately, BACS, MCCB, and CSB stood out as the top three performance-based measures. While, CAI ranked first from interview-based measures, followed by Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS), and Self-Assessment Scale of Cognitive Complaints in Schizophrenia (SASCCS). See Table 5.

Methodological quality

From the ten domains of the COSMIN checklist, two domains (responsiveness to change and measurement error) were not reported in any of the included articles. We have not evaluated patient-reported outcome development check box (box 1), since this study focuses on adaptation studies rather than development studies and most measures included here are not freely available. Most of the included studies reported hypothesis testing (n = 25/28). For a summary of the methodological qualities of the included studies, see Fig. 3.

Quality of the included studies ranged from very good to inadequate. Thirteen studies were rated very good quality for internal consistency; while 5/19 studies were rated as doubtful, and one inadequate-quality rating. The main reason for the doubtful rating in those studies was that there were minor methodological problems and the reason for the inadequate-quality rating was that internal consistency was not calculated for each dimensions of the scale. None of the studies that assessed test–retest reliability had very good rating and the reason for this was that it is doubtful that the time interval used was appropriate (5/10 doubtful rating). All the 10 studies that evaluated content validity were found to have doubtful quality. The reason is that in all studies, it is not clear the methodology they followed (not clear whether the group moderator was trained, topic guide was used, group meetings were recorded, etc.). From the 10 studies that evaluated structural validity, one study had very good quality, four studies had adequate quality, another four doubtful rating, and one inadequate quality. The reason for the inadequate rating was that they used a very small sample. Most of the included studies (n = 25) examined one form of hypothesis testing (i.e., concurrent, convergent, or known group validity). Most of the studies were rated as very good (n = 18/25) and the remaining were rated as doubtful (n = 7/25). The main reason for the doubtful rating was that minor methodological problems in sample selection. The quality of all studies that evaluated cross-cultural validity was rated as doubtful (n = 15/15). The main reason for this was that multiple group factor analysis was not performed, it is not clear whether the samples are similar, and the approaches used to analyze the data are not clear. Finally, four studies evaluated criterion validity—two very good quality and two doubtful quality. Figure 3 presents the methodological quality scores for each of the included studies. Detailed report of the quality rating for each study at each measurement property is given as online resources 4.

Discussion

There is limited availability of valid and reliable cognitive assessment and screening instruments for people with SMDs in LMICs. This is partly due to the limited adaptation and validation efforts in the literature. A first step to improving this situation is to systematically assess the current status of the literature and identify cognitive measures which are already validated and may be used and adapted for the assessment of cognition in people with SMDs in LMICs.

This review identified 28 studies and 23 independent cognitive measures. Most of the measures evaluated cognition in PWS from upper-middle-income countries such as Brazil and China. None of the studies was from low-income settings, suggesting that we have no evidence about the psychometric properties of these measures in low-income countries. We found participants’ education level to be high (on average 11 years of education). The majority of the studies had low methodological quality, and based on limited sample size. This was more so in cross-cultural validation and content validity studies.

According to the criteria that we considered for clinical and research usefulness, we recommend BACS, CAI, MCCB, and CSB as most suitable measures to be adapted for the cognitive assessment of PWS in LMICs. Of these, the BACS is the most frequently evaluated measure and it is the measure with most adaptations and reliable psychometric properties. In addition, it addresses comprehensive domains of neurocognition with shorter administering time. Since LMICs have different contexts in terms of cultural, linguistic, economic, and educational backgrounds, we recommend validation studies at different sites with the above three measures as a starting point for validation and adaptation of other measures. Studies focusing on norming of measures in LMICs would also be useful. The use and adaptation of a measure to a new context requires considering carefully how the new version of the measure will interact with the new context and population [70,71,72]. Assessment of psychometric properties is the result of an interaction between the measure, the context, and the population. Adapting measures to LMICs requires a fundamental shift in each of these aspects, and therefore, the literature and evidence on existing measures can only have a limited value to inform the adaptation process [73, 74].

More than half of the measures included in this review do not assess social cognition (n = 13/22) which is a domain usually found impaired in PWS. We recommend clinicians and researchers in LMICs to consider measures that can include this domain, although the different social and contextual factors may be a challenge in developing comparable social cognition tests.

We did not find studies conducted in low-income countries, the majority of the studies were from upper-middle-income countries (e.g., from Brazil and China). This is an important finding as it highlights a clear gap in the literature and availability of cognitive measures globally. The context in low-income countries is different from upper-middle-income and higher-income countries. For example, according to the World Bank, 67% of the total population in lower-income countries are rural residents, who may not be literate [75]. Overall only 63% have basic literacy skills (able to read and write a simple sentence) and may not be familiar with settings outside their local community. LMICs are diverse in terms of educational status, culture, and language. With this in mind, it is important that local experts lead the adaptation efforts on cognitive measures in LMICs, using the recommended measures in this review as an initial point.

The average educational level of PWSSD in the included studies was approximately 11 years, which shows that the findings reported here may not translate directly to low-income settings where the overall literacy rate tends to be lower. Researchers need to consider the effect of education [76,77,78], culture [79, 80], and language [81] when deciding which measure to adapt and use in LMICs’ context.

It should be borne in mind that a low score on a cognitive test may not always reflect cognitive impairment, but simply lack of familiarity with the material presented. LMICs are also diverse in cultural practice, which should be considered during the adaptation process. For example, one item of SCoRS [82] requires the participant to assess how difficult it is for them to follow a television show. Answering this item has clear economic and cultural implications. Adaptation of this item may require a fundamental rethink in relation to the setting. The other factor that should be considered is language. Again, LMICs are less homogeneous in langue knowledge and use. In many countries in Africa and Asia, multiple languages are spoken within a given country, and it may not be simple to define people’s first language. Using a cognitive measure adapted in a different linguistic context may not be appropriate and non-verbal cognitive measures may be preferred. This further emphasized the question of how much context influence cognitive assessment [83]. The literature shows that different results in a cognitive test can be due to variation in cultural interpretations, such as when a test has items or tasks that are only familiar in certain contexts [79].

This review has a number of strengths in that we included any measure of cognition in people with SMDs with no restriction in the domain of cognition evaluated. We also followed a rigorous protocol, which we preregistered in PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/), searched four comprehensive databases without restriction on the date of publication, and used a comprehensive quality assessment tool (the COSMIN criteria) [33].

However, our review has limitations. First, the broad scope of the review makes the data inappropriate for meta-analysis. Our study protocol allowed a wide variety of study outcomes to obtain a broad overview of the field given the paucity of knowledge and lack of prior systematic reviews. Second, the criteria we used to rank the measures were not used previously (even though we adapted them from previous reviews). Third, this review excluded non-English studies, which might limit the generalizability of the findings. Fourth, gray literature was not searched; however, we conducted forward and backward-searching which extended our included studies from 21 to 28. Readers are recommended to consider the generalizability of our review considering those limitations.

Reviewing and systematically assessing the psychometric properties of measures in this field are useful for researchers, clinicians, and policymakers in LMICs and beyond. Since LIMICs are diverse in language, culture, and education, our recommendations may not work for every country, and hence, these need to be contextualized. This review could help researchers in measure selection when planning studies, particularly for adaptation studies. Other potential use includes guiding choices of the best measures in conducting longitudinal studies to assess change in cognition and clinical trials for interventions aiming to improve cognition. In this review, we considered measurement properties such as test–retest reliability, learning effect, tolerability, and practicality which are important in repeated assessment. Therefore, researchers can compare measures on those criteria when looking for the best measures for longitudinal studies and clinical trials. Clinicians in LMICs could use this review to compare different measures and use the one that most suits their specific needs and context. Policymakers can use the results of this study to design prevention and treatment strategies regarding cognition in people with SMDs—such as developing a guideline, integrating routine assessment of cognition in clinical settings, and promoting research activities in the treatment of cognitive impairment. This review points clearly to a gap in the evidence for cognitive assessment for SMDs in LMICs. This may suggest a gap in the use of cognitive assessment in clinical practice and the need for adaptation and validation study to make these tools available to services, clinicians, and service users.

Availability of data and materials

All the data used made available in the manuscript and supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- AJOL:

-

African Journals Online

- BACS:

-

Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia

- CAI:

-

Cognitive Assessment Interview

- COBRA:

-

Cognitive complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments

- CSB:

-

CogState Battery

- DALYs:

-

Disability-Adjusted Life Years

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders

- FAB:

-

Frontal Assessment Battery

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- ICC:

-

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

- LMICs:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- MCCB:

-

MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery

- NBSC:

-

The New Cognitive Battery for patients with Schizophrenia in China

- PDQ-D:

-

Perceived Deficit Questionnaire-Depression

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PWBD:

-

People with bipolar disorder

- PWD:

-

People with Depression

- PWS:

-

People with Schizophrenia

- PWSSD:

-

People with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

- RBANS:

-

Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status

- RMET:

-

Reading the Mind in the Eye Test

- SASCCS:

-

Self-assessment scale of cognitive complaints in schizophrenia

- SCoRS:

-

Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale

- SMDs:

-

Severe Mental Disorders

- YLD:

-

Years Lived with Disability

References

Bachrach LL (1988) Defining chronic mental illness: a concept paper. Hosp Community Psychiatry 39(4):383–388. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.39.4.383

Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392(10159):1789–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

Schaefer J, Giangrande E, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D (2013) The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res 150(1):42–50

Fioravanti M, Bianchi V, Cinti ME (2012) Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: an updated metanalysis of the scientific evidence. BMC Psychiatry 12(1):64

Bora E, Harrison B, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2013) Cognitive impairment in euthymic major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 43(10):2017–2026

Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2010) Cognitive impairment in affective psychoses: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 36(1):112–125

Bora E, Pantelis C (2015) Meta-analysis of cognitive impairment in first-episode bipolar disorder: comparison with first-episode schizophrenia and healthy controls. Schizophr Bull 41(5):1095–1104

Habtewold TD, Rodijk LH, Liemburg EJ, Sidorenkov G, Boezen HM, Bruggeman R, Alizadeh BZ (2020) A systematic review and narrative synthesis of data-driven studies in schizophrenia symptoms and cognitive deficits. Transl Psychiatry 10(1):244. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00919-x

Shahrokh NC, Hales RE, Phillips KA, Yudofsky SC (2011) The language of mental health: a glossary of psychiatric terms. 1st edn. American Psychiatric Publishing

Trotta A, Murray R, MacCabe J (2015) Do premorbid and post-onset cognitive functioning differ between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 45(2):381–394

Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2009) Cognitive functioning in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and affective psychoses: meta-analytic study. Br J Psychiatry 195(6):475–482

Krabbendam L, Arts B, van Os J, Aleman A (2005) Cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a quantitative review. Schizophr Res 80(2–3):137–149

Stefanopoulou E, Manoharan A, Landau S, Geddes JR, Goodwin G, Frangou S (2009) Cognitive functioning in patients with affective disorders and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 21(4):336–356

Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK (2004) Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 72(1):29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007

Martino DJ, Samamé C, Ibañez A, Strejilevich SA (2015) Neurocognitive functioning in the premorbid stage and in the first episode of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res 226(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.12.044

Ahern E, Semkovska M (2017) Cognitive functioning in the first-episode of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology 31(1):52–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000319

Chang WC, Hui CL, Chan SK, Lee EH, Chen EY (2016) Impact of avolition and cognitive impairment on functional outcome in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorder: a prospective one-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res 170(2–3):318–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.004

El-Missiry A, Elbatrawy A, El Missiry M, Moneim DA, Ali R, Essawy H (2015) Comparing cognitive functions in medication adherent and non-adherent patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 70:106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.09.006

Alptekin K, Akvardar Y, Kivircik Akdede BB, Dumlu K, Isik D, Pirincci F, Yahssin S, Kitis A (2005) Is quality of life associated with cognitive impairment in schizophrenia? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 29(2):239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.006

Hofer A, Biedermann F, Yalcin N, Fleischhacker W (2010) Neurocognition and social cognition in patients with schizophrenia or mood disorders (Neurokognition und soziale Kognition bei Patienten mit schizophrenen und affektiven Störungen). Neuropsychiatr 24(3):161–169

Vlad M, Raucher-Chéné D, Henry A, Kaladjian A (2018) Functional outcome and social cognition in bipolar disorder: is there a connection? Eur Psychiatry 52:116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.05.002

Fett A-KJ, Velthorst E, Reichenberg A, Ruggero CJ, Callahan JL, Fochtmann LJ, Carlson GA, Perlman G, Bromet EJ, Kotov R (2019) Long-term changes in cognitive functioning in individuals with psychotic disorders: findings from the suffolk county mental health project. JAMA Psychiat. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3993.10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3993

Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L (2004) the brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res 68(2–3):283–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011

Maruff P, Thomas E, Cysique L, Brew B, Collie A, Snyder P, Pietrzak RH (2009) Validity of the CogState brief battery: relationship to standardized tests and sensitivity to cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia, and AIDS dementia complex. Arch Clin Neuropsychol Off J Natl Acad Neuropsychol 24(2):165–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acp010

Mayer J (2002) MSCEIT: Mayer-Salovey-Caruso emotional intelligence test. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems

Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese PD III, Frederick J, Gold JM (2008) The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry 165(2):203–213

Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN (1998) The repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 20(3):310–319. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823

Wechsler D (1997) Wechsler memory scale (WMS-III), vol 14. Psychological corporation, San Antonio

Bakkour N, Samp J, Akhras K, El Hammi E, Soussi I, Zahra F, Duru G, Kooli A, Toumi M (2014) Systematic review of appropriate cognitive assessment instruments used in clinical trials of schizophrenia, major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 216(3):291–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.014

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):1000097

APA (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub

Who WHO (1992) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines, vol 1. World Health Organization

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB (2018) COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil 27(5):1147–1157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3

Mokkink LB, de Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, Terwee CB (2018) COSMIN Risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil 27(5):1171–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4

Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, Westerman MJ, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW, Mokkink LB (2018) COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil 27(5):1159–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2012) Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil 21(4):651–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1

Rnic K, Linden W, Tudor I, Pullmer R, Vodermaier A (2013) Measuring symptoms in localized prostate cancer: a systematic review of assessment instruments. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 16(2):111–122. https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2013.1

Sousa VEC, Dunn Lopez K (2017) Towards usable E-health a systematic review of usability questionnaires. Appl Clin Inform 8(2):470–490. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2016-10-R-0170

Arkins B, Begley C, Higgins A (2016) Measures for screening for intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 23(3–4):217–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12289

Therrien Z, Hunsley J (2012) Assessment of anxiety in older adults: a systematic review of commonly used measures. Aging Ment Health 16(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.602960

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Erlbaum, Hillsdle

Araujo GE, Resende CB, Cardoso AC, Teixeira AL, Keefe RS, Salgado JV (2015) Validity and reliability of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the BACS (Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia). Clin (Sao Paulo, Braz) 70(4):278–282. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2015(04)10

Salgado JV, Carvalhaes CFR, Pires AM, Neves M, Cruz BF, Cardoso CS, Lauar H, Teixeira AL, Keefe RSE (2007) Sensitivity and applicability of the Brazilian version of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS). Dementia Neuropsychol 1(3):260–265. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1980-57642008dn10300007

Dias FLDC, Teixeira AL, Guimaraes HC, Barbosa MT, Resende EDPF, Beato RG, Carmona KC, Caramelli P (2017) Cognitive performance of community-dwelling oldest-old individuals with major depression: the Pieta study. Int Psychogeriatr 29(9):1507–1513

Fonseca AO, Berberian AA, de Meneses-Gaya C, Gadelha A, Vicente MDO, Nuechterlein KH, Bressan RA, Lacerda ALT (2017) The Brazilian standardization of the MATRICS consensus cognitive battery (MCCB): psychometric study. Schizophr Res 185:148–153

Negrão J, Akiba HT, Lederman VRG, Dias ÁM (2016) Faux pas test in schizophrenic patients (Teste de Faux Pas em pacientes com esquizofrenia). J Bras Psiquiatr 65(1):17–21

Sanvicente-Vieira B, Brietzke E, Grassi-Oliveira R (2012) Translation and adaptation of theory of mind tasks into Brazilian portuguese (Tradução e adaptação de tarefas de Teoria da Mente para o português brasileiro). Trends Psychiatry Psychother (Impr) 34(4):178–185

Lima FM, Cardoso TA, Serafim SD, Martins DS, Solé B, Martínez-Arán A, Vieta E, Rosa AR (2018) Validity and reliability of the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment (COBRA) in Brazilian bipolar patients (Validade e fidedignidade da Escala de Disfunções Cognitivas no Transtorno Bipolar (COBRA) em pacientes bipolares brasileiros). Trends Psychiatry Psychother (Impr) 40(2):170–178

Mehta UM, Thirthalli J, Naveen Kumar C, Mahadevaiah M, Rao K, Subbakrishna DK, Gangadhar BN, Keshavan MS (2011) Validation of social cognition rating tools in indian setting (SOCRATIS): a new test-battery to assess social cognition. Asian J Psychiatry 4(3):203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2011.05.014

Johnson I, Kebir O, Ben Azouz O, Dellagi L, Rabah Y, Tabbane K (2009) The self-assessment scale of cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: a validation study in Tunisian population. BMC Psychiatry 9:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-9-66

Muliady S, Malik K, Amir N, Kaligis F (2019) Validity and reliability of the indonesian version of brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia (BACS-I). J Int Dent Med Res 12(1):263–267

Azizian A, Yeghiyan M, Ishkhanyan B, Manukyan Y, Khandanyan L (2011) Clinical validity of the repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status among patients with schizophrenia in the Republic of Armenia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 26(2):89–97

Bosgelmez S, Yildiz M, Yazici E, Inan E, Turgut C, Karabulut U, Kircali A, Tas HI, Yakisir SS, Cakir U, Sungur MZ (2015) Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of cognitive assessment interview (CAI-TR). Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni Bull Clin Psychopharmacol 25(4):365–380

Gulec H, Kavakci O, Gulec MY, Kucukali CI, Citak S (2008) The validity and reliability of Turkish version of frontal assessment battery in patients with schizophrenia. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res 14(4):165–168

Mazhari S, Ghafaree-Nejad AR, Soleymani-Zade S, Keefe RSE (2017) Validation of the Persian version of the schizophrenia cognition rating scale (SCoRS) in patients with schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr 27:12–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.02.007

Mazhari S, Parvaresh N, Eslami Shahrbabaki M, Sadeghi MM, Nakhaee N, Keefe RS (2014) Validation of the Persian version of the brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 68(2):160–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12107

Ruzita J, Zahiruddin O, Kamarul Imran M, Muhammad Najib Muhammad A (2009) Validation of the malay version of auditory verbal learning test (MVAVLT) among schizophrenia patients in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia (HUSM), Malaysia. ASEAN J Psychiatry 10:54–74

Shi C, Kang L, Yao S, Ma Y, Li T, Liang Y, Cheng Z, Xu Y, Shi J, Xu X (2019) What is the optimal neuropsychological test battery for schizophrenia in China? Schizophr Res 208:317–323

Zhong N, Jiang H, Wu J, Chen H, Lin S, Zhao Y, Du J, Ma X, Chen C, Gao C (2013) Reliability and validity of the CogState battery Chinese language version in schizophrenia. PLoS ONE 8(9):e74258

Abdullah H, Osman ZJ, Alwi MNM, Shah SA, Ibrahim N, Baharuddin A, Jaafar NRN, Said SM, Rahman HA, Bahari R (2013) Reliability and validity of the malay version of the brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia (BACS): preliminary results. Eur J Soc Behav Sci 5(2):920

Morozova A, Garakh Z, Bendova M, Zaytseva Y (2017) Comparative analysis of theory of mind tests in first episode psychosis patients. Psychiatr Danub 29(3):285–288

Aydemir O, Cokmus FP, Akdeniz F, Suculluoglu Dikici D, Balikci K (2017) Psychometric properties of the Turkish versions of perceived deficit questionnaire-depression and british columbia cognitive complaints inventory. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi 18(3):224–230

Shi C, Wang G, Tian F, Han X, Sha S, Xing X, Yu X (2017) Reliability and validity of Chinese version of perceived deficits questionnaire for depression in patients with MDD. Psychiatry Res 252:319–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.021

Xiao L, Lin X, Wang Q, Lu D, Tang S (2015) Adaptation and validation of the “cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment” (COBRA) in Chinese bipolar patients. J Affect Disord 173:226–231

Yoldi-Negrete M, Fresan-Orellana A, Martinez-Camarillo S, Ortega-Ortiz H, Juarez Garcia FL, Castaneda-Franco M, Tirado-Duran E, Becerra-Palars C (2018) Psychometric properties and cross-cultural comparison of the cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment (COBRA) in Mexican patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 269:536–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.098

Changiz R, Razieh H, Norolah M (2011) The utility of the Wisconsin card sorting test in differential diagnosis of cognitive disorders in Iranian psychiatric patients and healthy subjects. Iran J Psychiatry 6(3):99–105

Fan HZ, Zhu JJ, Wang J, Cui JF, Chen N, Yao J, Tan SP, Duan JH, Pang HT, Zou YZ (2019) Four-subtest index-based short form of WAIS-IV: psychometric properties and clinical utility. Arch Clin Neuropsychol Off J Natl Acad Neuropsychol 34(1):81–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acy016

Pieters HC, Sieberhagen JJ (1986) Evaluation of two shortened forms of the SAWAIS with three diagnostic groups. J Clin Psychol 42(5):809–815

Tuncay N, Kayserili G, Eser E, Zorlu Y, Akdede BB, Yener G (2013) Validation and reliability of the frontal assesment battery FAB in Turkish Frontal degerlendirme bataryasi{dotless}ni{dotless}n (FDB) Turkcede gecerlilik ve guvenilirligi.). J Neurol Sci 30(3):502–514

Acquadro C, Patrick DL, Eremenco S, Martin ML, Kuliś D, Correia H, Conway K (2017) Emerging good practices for translatability assessment (TA) of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures. J Pat Rep Outcomes 2(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-018-0035-8

Eremenco S, Pease S, Mann S, Berry P (2017) Patient-reported outcome (PRO) consortium translation process: consensus development of updated best practices. J Pat Rep Outcomes 2(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-018-0037-6

Skevington SM (2002) Advancing cross-cultural research on quality of life: observations drawn from the WHOQOL development World Health Organisation quality of life assessment. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil 11(2):135–144. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015013312456

Dichter MN, Schwab CG, Meyer G, Bartholomeyczik S, Halek M (2016) Linguistic validation and reliability properties are weak investigated of most dementia-specific quality of life measurements-a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 70:233–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.002

Hurst JR, Agarwal G, van Boven JFM, Daivadanam M, Gould GS, Wan-Chun Huang E, Maulik PK, Miranda JJ, Owolabi MO, Premji SS, Soriano JB, Vedanthan R, Yan L, Levitt N (2020) Critical review of multimorbidity outcome measures suitable for low-income and middle-income country settings: perspectives from the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) researchers. BMJ Open 10(9):e037079. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037079

Bank W (2018). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?end=2018&locations=XM&start=1960&view=chart.

Falch T, Massih SS (2011) The effect of education on cognitive ability. Econ Inq 49(3):838–856

Guerra-Carrillo B, Katovich K, Bunge SA (2017) Does higher education hone cognitive functioning and learning efficacy? Findings from a large and diverse sample. PLoS ONE 12(8):e0182276. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182276

Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM (2018) How much does education improve intelligence? A meta-analysis. Psychol Sci 29(8):1358–1369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618774253

Ardila A (2005) Cultural values underlying psychometric cognitive testing. Neuropsychol Rev 15(4):185–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-005-9180-y

Byrd DA, Walden Miller S, Reilly J, Weber S, Wall TL, Heaton RK (2006) Early environmental factors, ethnicity, and adult cognitive test performance. Clin Neuropsychol 20(2):243–260

Carstairs JR, Myors B, Shores EA, Fogarty G (2006) Influence of language background on tests of cognitive abilities: Australian data. Aust Psychol 41(1):48–54

Keefe RS, Davis VG, Spagnola NB, Hilt D, Dgetluck N, Ruse S, Patterson TD, Narasimhan M, Harvey PD (2015) Reliability, validity and treatment sensitivity of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25(2):176–184

Nisbett RE, Miyamoto Y (2005) The influence of culture: holistic versus analytic perception. Trends Cogn Sci 9(10):467–473

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Helen Jack for providing a 2-week systematic review training and shaping the scope as well as the search terms of this review. Our special thanks go to staffs of the department of psychiatry, Addis Ababa University, who provided valuable comments on different occasions. We would also like to thank Debre Berhan University for sponsoring the primary investigator to conduct this review. Finally, we would like to thank the African Mental Health Research Initiative (AMARI), because this work was supported by the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01] through the first author (YG). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [DEL-15-01] and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government.

Funding

This work was supported by the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01] through the first author (YG). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [DEL-15-01] and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, WellcomeTrust or the UK government. The funder has no role in the interpretation of findings and decision for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YG, AA, KH, and MC conceived and designed the study. YG and AD are involved in screening, extraction, and quality assessment. YG drafted the manuscript. All the authors read the manuscript several times and have given their final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University (Protocol No: 042/19/PSY).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haile, Y.G., Habatmu, K., Derese, A. et al. Assessing cognition in people with severe mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of assessment measures. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57, 435–460 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02120-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02120-x