Abstract

Purpose

Few studies have examined the course of maternal depressive across pregnancy and early parenthood. The aim of this study was to identify the physical, sexual and social health factors associated with the trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum.

Method

Data were drawn from 1102 women participating in the Maternal Health Study, a prospective pregnancy cohort study in Melbourne, Australia. Self-administered questionnaires were completed at baseline (<24 weeks gestation), and at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18 months, and 4 years postpartum.

Results

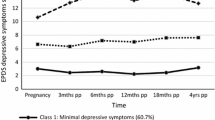

Latent class analysis modelling identified three distinct classes representing women who experienced minimal depressive symptoms (58.4%), subclinical symptoms (32.7%), and persistently high symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum (9.0%). Risk factors for subclinical and persistently high depressive symptoms were having migrated from a non-English speaking country, not being in paid employment during pregnancy, history of childhood physical abuse, history of depressive symptoms, partner relationship problems during pregnancy, exhaustion at 3 months postpartum, three or more sexual health problems at 3 months postpartum, and fear of a partner since birth at 6 months postpartum.

Conclusions

This study highlights the complexity of the relationships between emotional, physical, sexual and social health, and underscores the need for health professionals to ask women about their physical and sexual health, and consider the impact on their mental health throughout pregnancy and the early postpartum.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gavin NI et al (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106:1071–1083

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2007) Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Manchester

Laursen BP, Hoff E (2006) Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill Palmer Q 52(3):377–389

Giallo R, Cooklin A, Nicholson JM (2014) Risk factors associated with trajectories of mothers’ depressive symptoms across the early parenting period: an Australian population-based longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health 17:115–125

Vliegen N, Casalin S, Luyten P (2014) The course of postpartum depression: a review of longitudinal studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry 22(1):1–22

Gaillard A et al (2014) Predictors of postpartum depression: prospective study of 264 women followed during pregnancy and postpartum. Psychiatry Res 215(2):341–346

Banti S et al (2011) From the third month of pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Prevalence, incidence, recurrence, and new onset of depression. Results from the Perinatal Depression-Research & Screening Unit study. Compr Psychiatry 52(4):343–351

Mora PA et al (2009) Distinct trajectories of perinatal depressive symptomatology: evidence from growth mixture modeling. Am J Epidemiol 169(1):24–32

Sutter-Dallay AL et al (2012) Evolution of perinatal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum in a low-risk sample: the MATQUID cohort. J Affect Disord 139:23–29

McCall-Hosenfeld J, Phiri K, Schaefer E, Junjia Z, Kjerulff K (2016) Trajectories of depressive symptoms throughout the peri- and postpartum period: results from the First Baby Study. J Womens Health 25:1112–1121

Van der Waerden J et al (2015) Predictors of persistent maternal depression trajectories in early childhood: results from the EDEN mother–child cohort study in France. Psychol Med 45(09):1999–2012

Ilona L et al (2015) Long-term trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms and their antenatal predictors. J Affect Disord 170:30–38

Pilkington PD, Whelan TA, Milne LC (2015) A review of partner-inclusive interventions for preventing postnatal depression and anxiety. Clin Psychol 19:63–75

Rivas C, Ramsay J, Sadowski L, Davidson LL, Dunne D, Eldridge S, Hegarty K, Taft A, Feder G (2015) Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12), art ID CD005043. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005043.pub3

Howard LM et al (2013) Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 10(5):1–16

Cooklin AR et al (2015) Maternal physical health symptoms in the first 8 weeks postpartum among primiparous Australian women. Birth 42(3):254–260

Woolhouse H et al (2014) Physical health after childbirth and maternal depression in the first 12 months post partum: results of an Australian nulliparous pregnancy cohort study. Midwifery 30(3):378–384

Brown S, Lumley J (2000) Physical health problems after childbirth and maternal depression at six to seven months postpartum. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 107(10):1194–1201

Gartland D et al (2010) Women’s health in early pregnancy: findings from an Australian nulliparous cohort study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 50(5):413–418

Glazener CM (1997) Sexual function after childbirth: women’s experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 104:330–335

McDonald E, Woolhouse H, Brown S (2015) Consultation about sexual health issues in the year after childbirth: a cohort study. Birth 42:354–361

Morof D et al (2003) Postnatal depression and sexual health after childbirth. Obstet Gynecol 102(6):1318–1325

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150(6):782–786

Murray D, Cox JL (1990) Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol 8(2):99–107

Cox J et al (1996) Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord 39:185–189

MacMillan HL et al (2013) Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: results from the Ontario Child Health Study. Child Abuse Negl 37:14–21

Hegarty K (1999) Measuring a multidimensional definition of domestic violence: prevalence of partner abuse in women attending general practice. University of Queensland, Brisbane

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2015) Mplus User’s Guide, Seventh Edition. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Brown S et al (2006) Maternal health study: a prospective cohort study of nulliparous women recruited in early pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 6:12

Davalos DB, Yadon C, Tregellas H (2012) Untreated prenatal maternal depression and the potential risks to offspring: a review. Arch Womens Ment Health 15:1–14

Backenstrass M et al (2006) A comparative study of nonspecific depressive symptoms and minor depression regarding functional impairment and associated characteristics in primary care. Compr Psychiatry 47:35–41

Cuijpers P, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S (2004) Minor depression: risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. J Affect Disord 79:71–79

Giallo R et al (2015) The emotional-behavioural functioning of children exposed to maternal depressive symptoms across pregnancy and early childhood: a prospective Australian pregnancy cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24:1233–1244

Gartland D et al (2016) Vulnerability to intimate partner violence and poor mental health in the first 4-year postpartum among mothers reporting childhood abuse: an Australian pregnancy cohort study. Arch Women’s Ment Health 19:1091–1100

Austin M-P, Marcé Society Position Statement Advisory Committee (2014) Marcé International Society position statement on psychosocial assessment and depression screening in perinatal women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 28:179–187

MacArthur C et al (2002) Effects of redesigned community postnatal care on womens’ health 4 months after birth: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 359:378–385

World Health Organization (2013) Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. WHO, Geneva

Hegarty K, Feder G, Ramsay J (2006) Identification of partner abuse in health care settings: should health professionals be screening? In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G (eds) Intimate partner abuse and health professionals. Elsevier, London, pp 79–92

Danaher BG, Milgrom J, Seeley JR, Stuart S, Schembri C, Tyler MS, Ericksen J, Lester W, Gemmill AW, Kosty DB, Lewinsohn P (2013) MomMoodBooster web-based intervention for postpartum depression: feasibility trial results. J Med Internet Res 15(11):e242. doi:10.2196/jmir.2876

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), VicHealth, and the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. RG and SB were supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship and a NHMRC Research Fellowship, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giallo, R., Pilkington, P., McDonald, E. et al. Physical, sexual and social health factors associated with the trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52, 815–828 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1387-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1387-8