Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

HbA1c is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), with 1% higher HbA1c levels associated with a 10–20% increased risk of CVD. Little is known about the association between change in HbA1c over time and cardiovascular risk in non-diabetic populations. This study examined the association between change in HbA1c over time and cardiovascular risk in a non-diabetic British population.

Methods

We used data on HbA1c collected at baseline and at a second health examination 3 years later among a population of 5,790 non-diabetic men and women who participated in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC)–Norfolk. The association between change in HbA1c over 3 years and incident cardiovascular events over the following 8 years was examined using multivariate Cox regression. We also examined whether information on change in HbA1c over time improved prediction of cardiovascular events over a single measure of HbA1c by comparing the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (aROC) and computing the net reclassification improvement.

Results

The mean change (SD) in HbA1c over 3 years was 0.13% (0.52). During 44,596 person-years of follow-up, 529 cardiovascular events occurred (incidence 11.9 per 1,000 person-years). Each 0.5% rise in HbA1c over 3 years was associated with a 9% increase in risk of a cardiovascular event (HR 1.09; 95% CI 1.01, 1.18) after adjustment for baseline HbA1c and other major cardiovascular risk factors. However, change in HbA1c was not associated with cardiovascular risk after adjustment for HbA1c at follow-up. Multivariate models with and without information on change in HbA1c over time showed a similar aROC of 0.78. Adding change in HbA1c to the model with HbA1c at follow-up did not improve risk classification.

Conclusions/interpretation

Addition of information on change in HbA1c over 3 years did not improve the prediction of CVD over and above information on HbA1c and other major cardiovascular risk factors from a single time point.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glycaemia is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), not only in those with diabetes but across the range of blood glucose values [1, 2]. Previous studies have suggested that HbA1c has a continuous and graded relationship with CVD, with 1% higher HbA1c levels associated with a 20% and 26% increased risk of CHD and total mortality, respectively [3, 4]. Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials of tight glycaemic control among patients with diabetes provide further evidence of a causal relationship between blood glucose and CVD [5, 6]. However, there are no trials of glucose-lowering therapy in people with non-diabetic hyperglycaemia that have reported a reduction in cardiovascular events [7]. Consequently, there remains uncertainty over the benefits of lowering blood glucose to prevent CVD in non-diabetic populations [2].

Previous studies examining the relationship between glycaemia and CVD were based on between-individual differences in levels of glycaemia [3, 4, 8]. Studies have tracked glycaemic control and CVD risk in individuals with diabetes, but glucose-lowering treatment contributes to change in glycaemia and other cardiovascular risk factors in these individuals. Little is known about change in glycaemia over time and its association with CVD in non-diabetic populations. If an association does exist, it is unclear whether information on change in glycaemia over time will improve prediction of cardiovascular events compared with a single measure of glycaemia and other major cardiovascular risk factors. In a large British prospective cohort, we examined: (1) the association between change in HbA1c over 3 years and risk of CVD; (2) whether information on change in HbA1c over time might improve prediction of CVD compared with information collected at a single time point.

Methods

Study design and population

We used data from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC)–Norfolk, a large population-based prospective study of men and women aged 40–79 years residing in the county of Norfolk, UK. Details of the study have been described elsewhere [9]. Between 1993 and 1997, 25,639 men and women attended a baseline health examination, which included a self-administered health and lifestyle questionnaire, medical history taking, physical examination and blood testing. Participants completed questionnaires about their personal and family history of disease, medication and lifestyle factors including smoking habits. They were asked whether a physician had ever told them that they had any of the conditions in a list that included diabetes, heart attack and stroke. Anthropometric and blood pressure measurements and non-fasting blood samples were also taken at the health assessment.

Information on HbA1c at baseline was available for around half of all participants, as funding for the test only became available in 1995. HbA1c was measured on fresh EDTA blood samples using high-performance liquid chromatography (Diamat Automated Glycated Hemoglobin Analyzer; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hemel Hemstead, UK), which was standardised to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) assay.

The study was approved by the Norwich District Health Authority Ethics Committee. All participants gave written informed consent. EPIC–Norfolk is similar to a nationally representative sample for anthropometric indices, blood pressure and serum lipids, albeit with a lower prevalence of cigarette smoking [9].

Participants were invited to attend a second health assessment after 3 years (1998–2001), at which identical measurements were taken, and 15,028 participants (59%) attended. Results from the health examinations on risk factors such as total cholesterol, blood pressure and HbA1c were reported to the participants’ general practitioners so that they could assume responsibility for follow-up, confirmation of the diagnosis and organisation of care.

We limited our analysis to individuals with complete data for HbA1c at the baseline and second health examinations (n = 6,372). Those with complete data on HbA1c were healthier than those without with regard to risk factors at baseline (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). We further excluded individuals with clinically diagnosed diabetes (self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes, diabetes medication or diet modification due to diabetes, diabetes identified on hospital records, diabetes registers or diabetes coded on death certificates) [10] at both health examinations (n = 245). We then excluded those with prior CVD at the baseline examination and those who developed a first CVD event up to the second health examination (n = 337), leaving 5,790 individuals for our main analyses. We calculated the change in HbA1c for each individual, the main exposure in this study, by subtracting baseline HbA1c values from values at the second health examination.

Follow-up and ascertainment of CVD

We followed up participants who were free of CVD at the time of their second health examination for the development of a first CVD event or death. We report results for follow-up from the second health examination to 31 March 2008, a median of 8.1 years (interquartile range 7.7–8.4). Incident CVD was defined as a composite of fatal or non-fatal CVD, including hospitalisation from CHD and stroke; or death from CHD, stroke or peripheral vascular disease. Vital status for all EPIC–Norfolk participants was obtained via death certification at the Office for National Statistics. Participants admitted to a hospital were identified by their National Health Service number. Hospitals were linked to the East Norfolk Health Authority database, which identifies all hospital contacts throughout England and Wales for Norfolk residents. Hospital record data and vital status information were complete for 95% and 99% of participants, respectively. Previous validation studies in this prospective cohort indicated high validity of such case ascertainment [11].

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics and change in HbA1c over 3 years were summarised by CVD outcome, using percentages, means (SD) and medians (interquartile ranges). We tested for differences between groups using χ 2 tests for categorical variables, and t tests or Kruskal–Wallis tests for normally or non-normally distributed continuous variables.

The distribution of HbA1c at baseline and the second health examination and change in HbA1c was approximately normal. We calculated the mean values of the three measures and tested whether the change in HbA1c over time was different from zero.

We calculated cardiovascular event rates by levels of baseline HbA1c (<5%, 5.0–5.4%, 5.5–5.9% and ≥6.0% [<30, 31–36, 37–41 and ≥42 mmol/mol, respectively]) and change in HbA1c over time (increased and unchanged or decreased). We computed Kaplan–Meier curves for groups characterised by different levels of baseline HbA1c, and for individuals with high and low values of baseline HbA1c (according to the median value in this population) and changes in HbA1c over time (increased vs decreased or unchanged). We also computed Kaplan–Meier curves using different cut-off points to define high/low values of baseline HbA1c (HbA1c values of 5.7% and 6.0% [39 and 42 mmol/mol] instead of the median value). The differences between groups with different baseline HbA1c and changes in HbA1c were tested using the logrank test.

To examine the independent association of HbA1c at baseline and HbA1c at follow-up and change in HbA1c over 3 years with CVD risk, we fitted five multivariate Cox proportional hazards models which included different variables as follows: (1) Model 1: HbA1c at baseline and change in HbA1c over 3 years; (2) Model 2: HbA1c at baseline, age, sex, smoking, a family history of CVD, systolic blood pressure and serum total cholesterol; (3) Model 3: HbA1c at baseline, change in HbA1c over 3 years, age, sex, smoking, a family history of CVD, systolic blood pressure and serum total cholesterol; (4) Model 4: HbA1c at follow-up, age, sex, smoking, a family history of CVD, systolic blood pressure and serum total cholesterol; (5) Model 5: HbA1c at follow-up, change in HbA1c over 3 years, age, sex, smoking, a family history of CVD, systolic blood pressure and serum total cholesterol.

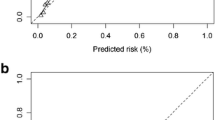

To determine whether information on change in HbA1c over 3 years improved risk prediction of the model which included HbA1c measured at baseline or follow-up, we compared the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (aROC) for the models with and without information on change in HbA1c, using a non-parametric method [12].

To account for concurrent changes in other risk factors, we adjusted for changes in systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and BMI. According to the new diagnostic criteria for diabetes, we performed sensitivity analyses to check if the main results would be altered when excluding those with an HbA1c ≥6.5% and ≥7.0% (≥48 and ≥53 mmol/mol).

For each model, we calculated the probability of CVD events over 8 years for each individual using methods previously described by D’Agostino et al [13], and then stratified participants into four risk categories (<5.0%, 5.0–9.9%, 10.0–19.9% and ≥20%). To demonstrate the benefits of using information on change in HbA1c over time for prediction of CVD in clinical practice, we calculated the net reclassification improvement (NRI) to determine whether information on change in HbA1c over time helped improve risk classification by the models with HbA1c at baseline or follow-up (Model 3 vs Model 2, and Model 5 vs Model 4) [14].

Results

Baseline characteristics of study population

The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarised in Table 1. The mean age of participants at baseline was 57.2 (SD 9.3) years, and 2,451 (42.3%) were male. Individuals who developed CVD were, on average, 8 years older than those who remained free of CVD. They were more likely to be male, current smokers, to have a family history of CVD, and be prescribed antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs, compared with those who did not develop CVD. Those who developed CVD also had higher baseline levels of BMI, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, triacylglycerol and HbA1c, and lower HDL-cholesterol values. There was no difference in social class between the two groups.

Change in HbA1c over time

Mean HbA1c values (SD) at baseline and the second health examination were 5.19% (33 mmol/mol) (0.58%) and 5.32% (35 mmol/mol) (0.47%), respectively. The mean difference between the two measures of HbA1c was 0.13% (0.52%) (p < 0.001).

Rates of cardiovascular events

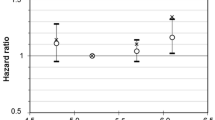

During 44,596 person-years of follow-up, there were 529 first CVD events, a cardiovascular event rate of 11.9 per 1,000 person-years. Figure 1 shows cardiovascular event rates in individuals with different levels of baseline HbA1c by change in HbA1c from baseline to the second health examination. Individuals whose HbA1c values increased over time were more likely to experience a cardiovascular event compared with those whose HbA1c values decreased or were unchanged, except for those with a baseline HbA1c <5.0% (<30 mmol/mol). Kaplan–Meier curves for individuals categorised by different levels of baseline HbA1c (Fig. 2) showed that levels of baseline HbA1c differed significantly with regard to development of a cardiovascular event over the follow-up period (logrank test, p < 0.001). Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for individuals with high and low values of baseline HbA1c (according to the median value of 5.2% [33 mmol/mol] in this population) and changes in HbA1c over time (increased vs unchanged or decreased). Individuals with a high baseline HbA1c value and whose HbA1c values increased over time were more likely to develop a cardiovascular event than were those with a similar baseline HbA1c but with unchanged or decreased HbA1c values over time and those with a low baseline HbA1c value (p < 0.001). However, in those with a low baseline HbA1c, change in HbA1c over time was not associated with the development of a cardiovascular event (Fig. 3). Similar findings were observed when HbA1c cut-off points of 5.7% and 6.0% (39 and 42 mmol/mol) were used instead of the median value.

Rates of first cardiovascular events over 8 years in individuals with different levels of baseline HbA1c by change in HbA1c between baseline and the second health examination. White bar, decreased or stable HbA1c over time; grey bar, increased HbA1c over time. A significant difference in cardiovascular event rates was observed in individuals with a baseline HbA1c 5.0–5.4% and 5.5–5.9% (p < 0.05). To convert values for HbA1c in % into mmol/mol, subtract 2.15 and multiply by 10.929

Kaplan–Meier curves for development of cardiovascular events in individuals with different levels of baseline HbA1c, with significant difference across groups (p < 0.001). Dotted line, HbA1c <5.0%; dashed line, HbA1c 5.0–5.4%; dashed–dotted line, HbA1c 5.5–5.9%; solid line, HbA1c ≥6.0%. To convert values for HbA1c in % into mmol/mol, subtract 2.15 and multiply by 10.929

Kaplan–Meier curves for development of cardiovascular events in individuals with high and low values of baseline HbA1c (according to the median value of 5.2% or 33 mmol/mol in this population) and change in HbA1c over time (increased, +ve; decreased or unchanged, −ve), with significant difference across groups (p < 0.001). Dotted line, low baseline HbA1c and −ve change; dashed line, low baseline HbA1c and +ve change; dashed–dotted line, high baseline HbA1c and −ve change; solid line, high baseline HbA1c and +ve change

Relative risk of cardiovascular events

Table 2 shows the risk of a first cardiovascular event (HR) for change in HbA1c over 3 years and other major cardiovascular risk factors including age, sex, smoking status, family history of CVD, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and use of lipid-lowering drugs. Change in HbA1c was significantly associated with cardiovascular risk. Each 0.5% increase in HbA1c over 3 years was associated with a 9% higher risk of CVD (HR 1.09; 95% CI 1.01, 1.18) after adjustment for baseline HbA1c and other major cardiovascular risk factors (Model 3). A 1% higher value of baseline HbA1c was associated with a 19% higher risk of CVD (HR 1.19; 95% CI 1.01, 1.39). These HRs remained unchanged after adjustment for temporal changes in levels of systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and BMI. When we further adjusted Model 3 for HDL-cholesterol and use of antihypertensive drugs, the association between change in HbA1c and CVD events was attenuated (HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.97, 1.15). Models with and without information on change in HbA1c over time showed similar discriminatory ability (aROC 0.78 [95% CI 0.76, 0.80] for both Models 2 and 3; p = 0.70). When adjusting for HbA1c at follow-up and other major risk factors, change in HbA1c over time was not associated with risk of CVD in the following 8 years (Model 5). As shown in Table 2, adding information on change in HbA1c over time did not improve predictive ability over information on HbA1c at follow-up (aROC 0.78 [95% CI 0.76, 0.80] for both Models 4 and 5; p = 0.99). We found similar results for every SD change in HbA1c (ESM Table 2). The main results were not altered when excluding individuals with HbA1c ≥6.5% and ≥7.0% (≥48 and ≥53 mmol/mol). The inclusion of information on change in HbA1c over time did not improve risk classification of the models with HbA1c at baseline or follow-up (Model 3 vs Model 2: NRI 0.30%, p = 0.71; Model 5 vs Model 4: NRI 0%, p = 0.50).

Discussion

We have shown that individuals whose HbA1c values increased over a period of 3 years had higher rates of cardiovascular events compared with those whose HbA1c values were unchanged or reduced over time. In multivariate regression models, change in HbA1c over time was associated with the risk of developing a CVD event independently of baseline HbA1c and other major cardiovascular risk factors. However, the association was not significant after adjustment for HbA1c at follow-up. Adding information on change in HbA1c over time to a model that included baseline HbA1c (or most recent HbA1c) and other major risk factors did not improve the prediction of CVD events with regard to discriminatory ability and risk classification.

Comparison with previous studies

Although previous studies reported that HbA1c is an important risk factor for CVD, little evidence exists regarding the association between change in measures of glycaemia over time and cardiovascular risk in general populations. Although some previous studies found no association between HbA1c and CVD risk [15, 16], data from a recent meta-analysis suggest that 1% higher HbA1c levels are associated with a 10–20% increased risk of CVD [3, 4], which is consistent with our results. Our finding that change in HbA1c values over time is independently associated with risk of CVD events, particularly in non-diabetic individuals with moderate-to-high baseline HbA1c values, adds to the evidence of a causal link.

Trial evidence to date suggests that cardiovascular risk may be reduced through tight glycaemic control in individuals with diabetes [5, 6]. However, there is still uncertainty about the effects of glucose-lowering approaches on cardiovascular risk in individuals with a lesser degree of dysglycaemia. The Nateglinide and Valsartan in Impaired Glucose Tolerance Outcomes Research (NAVIGATOR) trial, which aimed to reduce CVD risk by means of a glucose-lowering drug among individuals with impaired glucose tolerance, was not able to show the beneficial effect as the trial did not meet its glycaemic control target [7]. In fact, while a small reduction in fasting plasma glucose levels was observed, 2 h postchallenge glucose was elevated in the intervention group compared with the control group. Similarly, the recently reported Outcome Reduction with Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial found no difference in cardiovascular outcomes over 6 years between those receiving basal insulin to target normal fasting plasma glucose level and those receiving standard care [17].

Implications

There is evidence to suggest that measuring glycaemia might contribute to the estimation of CVD risk in addition to other major cardiovascular risk factors. One example is the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) risk engine, which incorporates HbA1c and other risk factors to estimate cardiovascular risk in people with diabetes [18]. The only cardiovascular risk score developed in the general population that includes measures of glycaemia (fasting plasma glucose and 2 h plasma glucose) is the Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative Analysis of Diagnostic Criteria in Europe (DECODE) risk score [19]. We have previously shown that the addition of HbA1c to the standard Framingham risk equation modestly improved its predictive ability in British men, but did not improve risk classification [20]. The present analysis suggests that, although information on change in HbA1c over 3 years was associated with cardiovascular risk independently of baseline HbA1c and other major risk factors, the potential contribution to risk prediction models appears limited.

Our results support the idea that approaches to lowering blood glucose might have the potential to prevent CVD among people with non-diabetic hyperglycaemia, although this needs to be confirmed by results from ongoing trials such as the Acarbose Cardiovascular Evaluation (ACE) trial (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00829660, accessed 24 Jan 2013). Alongside this high-risk approach, our results also provide support for population-based prevention strategies [21]. A rise in the mean value of HbA1c over 3 years observed in this study points to a shift in the distribution of glycaemia in the non-diabetic population over a relatively short time. Interventions to shift the distribution of glycaemia, and other risk factors, in the opposite direction, or to reduce the magnitude of the observed shift, are likely to be associated with a reduction in the population burden of CVD.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the association between change in HbA1c and future risk of CVD. We used data from a large population-based prospective study with robust ascertainment of cardiovascular outcomes over a long follow-up. However, to address our research question, we included only participants with complete data on HbA1c at baseline and the second health examination, who were generally healthier than those excluded, according to their baseline risk factor profiles (ESM Table 1). As HbA1c testing became available in 1995, most participants enrolled between 1993 and 1994 were excluded (missing by design). These participants were less healthy than those included in our main analysis. This is likely to have led to underestimation of the true cardiovascular risk in the whole cohort and might therefore have influenced estimates of the association between change in HbA1c and CVD risk.

As the baseline and second health examinations in EPIC–Norfolk took place in the 1990s and early 2000s, before the introduction of new HbA1c diagnostic criteria [22], in our main analysis we did not exclude those with an HbA1c ≥6.5% (≥48 mmol/mol) at either health examination, as we assumed that they were not prescribed any glucose-lowering treatment. Furthermore, as results for HbA1c were sent to participants’ general practitioners, those with an HbA1c ≥7.0% (≥53 mmol/mol) at the time were assumed to have been followed up and a diagnosis of diabetes confirmed and recorded in diabetes registers and clinical records. These participants would therefore be captured by our methods of diabetes ascertainment using multiple sources of information. In fact, a previous capture–recapture analysis in this cohort showed that this method of ascertainment identified 99% of all clinically incident cases of diabetes, when compared with diagnostic information from a comprehensive review of clinical records [23]. Moreover, in our sensitivity analyses the exclusion of individuals with an HbA1c ≥6.5% or ≥7.0% (≥48 or ≥53 mmol/mol) did not alter the main results.

It is possible that regression to the mean in HbA1c may have altered the result of the association between change in HbA1c and CVD risk. For example, individuals with a larger increase in HbA1c over time tended to be those with a lower baseline HbA1c, who were actually at lower risk of CVD. This might have led to an underestimation of the association between change in HbA1c and CVD risk. As HbA1c increases with age, we have taken into account the possible effect of increasing age on the association between change in HbA1c over time and CVD risk by adjusting the association for age and other risk factors. HbA1c values are influenced by some disorders affecting the lifespan of erythrocytes, such as haemoglobinopathy [22]. However, these conditions are rare in this white population. Last, as 99% of EPIC–Norfolk participants were white, the generalisability of our findings to other ethnic groups and populations might be limited.

We conclude that the inclusion of information on change in HbA1c over time did not improve prediction of CVD over and above information on HbA1c and other major cardiovascular risk factors at a single time point in this non-diabetic British population.

Abbreviations

- aROC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- EPIC–Norfolk:

-

European Prospective Investigation of Cancer–Norfolk

- NRI:

-

Net reclassification improvement

References

Khaw KT, Wareham N (2006) Glycated hemoglobin as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Curr Opin Lipidol 17:637–643

Gerstein HC (2010) More insights on the dysglycaemia–cardiovascular connection. Lancet 375:2195–2196

Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, Luben R, Welch A, Day N (2004) Association of hemoglobin A1c with cardiovascular disease and mortality in adults: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk. Ann Intern Med 141:413–420

Sarwar N, Aspelund T, Eiriksdottir G et al (2010) Markers of dysglycaemia and risk of coronary heart disease in people without diabetes: Reykjavik prospective study and systematic review. PLoS Med 7:e1000278

Turnbull FM, Abraira C, Anderson RJ et al (2009) Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 52:2288–2298, Erratum 52:2470

Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S et al (2009) Effect of intensive control of glucose on cardiovascular outcomes and death in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 373:1765–1772

NAVIGATOR Study Group (2010) Effect of nateglinide on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 362:1463–1476

Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H et al (2010) Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med 362:800–811

Day N, Oakes S, Luben R et al (1999) EPIC–Norfolk: study design and characteristics of the cohort. European Prospective Investigation of Cancer. Br J Cancer 80(Suppl 1):95–103

Chamnan P, Simmons RK, Forouhi NG et al (2011) Incidence of type 2 diabetes using proposed HbA1c diagnostic criteria in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer–Norfolk cohort: implications for preventive strategies. Diabetes Care 34:950–956

Boekholdt SM, Peters RJ, Day NE et al (2004) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor and the risk of myocardial infarction or death due to coronary artery disease in adults without prior myocardial infarction or stroke: the EPIC–Norfolk prospective population study. Am J Med 117:390–397

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL (1988) Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44:837–845

D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ et al (2008) General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 117:743–753

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, D’Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS (2008) Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 27:157–172

Pradhan AD, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM (2007) Hemoglobin A1c predicts diabetes but not cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic women. Am J Med 120:720–727

Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Ebrahim S (2006) Does the new International Diabetes Federation definition of the metabolic syndrome predict CHD any more strongly than older definitions? Findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Diabetologia 49:41–48

Gerstein HC, Bosch J, Dagenais GR et al (2012) Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med 367:319–328

Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, Stratton IM (2001) The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes (UKPDS 56). Clin Sci (Lond) 101:671–679

Balkau B, Hu G, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, Borch-Johnsen K, Pyorala K (2004) Prediction of the risk of cardiovascular mortality using a score that includes glucose as a risk factor. The DECODE Study. Diabetologia 47:2118–2128

Simmons RK, Sharp S, Boekholdt SM et al (2008) Evaluation of the Framingham risk score in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer-Norfolk cohort: does adding glycated hemoglobin improve the prediction of coronary heart disease events? Arch Intern Med 168:1209–1216

Rose G (2001) Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 30:427–432, discussion 433–424

Association AD (2010) Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 33(Suppl 1):S62–S69

Harding AH, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ (2006) Population impact of strategies for identifying groups at high risk of type 2 diabetes. Prev Med 42:364–368

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the EPIC–Norfolk participants and the EPIC–Norfolk team.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Medical Research Council, Cancer Research UK, British Heart Foundation, European Union (Europe Against Cancer Programme), Stroke Association, Wellcome Trust, Research into Ageing, and Academy of Medical Science. P. Chamnan is supported by a Royal Thai Government scholarship. S. J. Griffin receives support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grant funding scheme (RP-PG-0606-1259). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

PC had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis. KTK and NJW take responsibility for the integrity of the data. PC, as the corresponding author, has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors.

PC, RKS and SJG were responsible for the study concept and design and drafting of the manuscript. KTK and NJW were responsible for the acquisition of the data. PC, RKS, NJW and SJG analysed and interpreted the data. All authors were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(PDF 72 kb)

ESM Table 2

(PDF 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chamnan, P., Simmons, R.K., Khaw, K.T. et al. Change in HbA1c over 3 years does not improve the prediction of cardiovascular disease over and above HbA1c measured at a single time point. Diabetologia 56, 1004–1011 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2854-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2854-8