Abstract

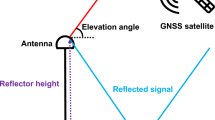

Where coastal tsunami hazard is governed by near-field sources, such as submarine mass failures or meteo-tsunamis, tsunami propagation times may be too small for a detection based on deep or shallow water buoys. To offer sufficient warning time, it has been proposed to implement early warning systems relying on high-frequency (HF) radar remote sensing, that can provide a dense spatial coverage as far offshore as 200–300 km (e.g., for Diginext Ltd.’s Stradivarius radar). Shore-based HF radars have been used to measure nearshore currents (e.g., CODAR SeaSonde® system; http://www.codar.com/), by inverting the Doppler spectral shifts, these cause on ocean waves at the Bragg frequency. Both modeling work and an analysis of radar data following the Tohoku 2011 tsunami, have shown that, given proper detection algorithms, such radars could be used to detect tsunami-induced currents and issue a warning. However, long wave physics is such that tsunami currents will only rise above noise and background currents (i.e., be at least 10–15 cm/s), and become detectable, in fairly shallow water which would limit the direct detection of tsunami currents by HF radar to nearshore areas, unless there is a very wide shallow shelf. Here, we use numerical simulations of both HF radar remote sensing and tsunami propagation to develop and validate a new type of tsunami detection algorithm that does not have these limitations. To simulate the radar backscattered signal, we develop a numerical model including second-order effects in both wind waves and radar signal, with the wave angular frequency being modulated by a time-varying surface current, combining tsunami and background currents. In each “radar cell”, the model represents wind waves with random phases and amplitudes extracted from a specified (wind speed dependent) energy density frequency spectrum, and includes effects of random environmental noise and background current; phases, noise, and background current are extracted from independent Gaussian distributions. The principle of the new algorithm is to compute correlations of HF radar signals measured/simulated in many pairs of distant “cells” located along the same tsunami wave ray, shifted in time by the tsunami propagation time between these cell locations; both rays and travel time are easily obtained as a function of long wave phase speed and local bathymetry. It is expected that, in the presence of a tsunami current, correlations computed as a function of range and an additional time lag will show a narrow elevated peak near the zero time lag, whereas no pattern in correlation will be observed in the absence of a tsunami current; this is because surface waves and background current are uncorrelated between pair of cells, particularly when time-shifted by the long-wave propagation time. This change in correlation pattern can be used as a threshold for tsunami detection. To validate the algorithm, we first identify key features of tsunami propagation in the Western Mediterranean Basin, where Stradivarius is deployed, by way of direct numerical simulations with a long wave model. Then, for the purpose of validating the algorithm we only model HF radar detection for idealized tsunami wave trains and bathymetry, but verify that such idealized case studies capture well the salient tsunami wave physics. Results show that, in the presence of strong background currents, the proposed method still allows detecting a tsunami with currents as low as 0.05 m/s, whereas a standard direct inversion based on radar signal Doppler spectra fails to reproduce tsunami currents weaker than 0.15–0.2 m/s. Hence, the new algorithm allows detecting tsunami arrival in deeper water, beyond the shelf and further away from the coast, and providing an early warning. Because the standard detection of tsunami currents works well at short range, we envision that, in a field situation, the new algorithm could complement the standard approach of direct near-field detection by providing a warning that a tsunami is approaching, at larger range and in greater depth. This warning would then be confirmed at shorter range by a direct inversion of tsunami currents, from which the magnitude of the tsunami would also estimated. Hence, both algorithms would be complementary. In future work, the algorithm will be applied to actual tsunami case studies performed using a state-of-the-art long wave model, such as briefly presented here in the Mediterranean Basin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that there is a misprint in equation (8) of the original paper by Barrick (1972a), where \(K_0\) should be replaced by \(K_0^4\), and a non-standard normalization of the directional spectrum resulting in a missing \(2^3\) factor, as compared to subsequent stabilized versions of the theory (Lipa and Barrick 1986).

References

Barrick DE (1972a) First-order theory and analysis of MF/HF/VHF scatter from the sea. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 20(1):2–10

Barrick DE (1972b) Remote sensing of sea state by radar. In: Remote sensing of the Troposphere, VE Derr, Editor, US Government, vol 12

Barrick DE (1978) HF radio oceanography: a review. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 13(1–4):23–43

Barrick DE (1979) A coastal radar system for tsunami warning. Remote Sensing of Environment 8(4):353–358

Benjamin LR, Flament P, Cheung KF, Luther DS (2015) The 2011 Tohoku tsunami south of Oahu: high-frequency Doppler radio observations and model simulations of currents. J Geophys Res (in review) pp 1–27

Booij N (1983) A Note on the Accuracy of the Mild-slope Equation. Coastal Engng 7:191–203

Crombie DD (1955) Doppler spectrum of sea echo at 13.56 Mc./s. Nature pp 681–682

Dean RG, Dalrymple RA (1984) Water Wave Mechanics for Engineers and Scientists. Prentice-Hall

Dzvonkovskaya A (2012) Ocean surface current measurements using HF radar during the 2011 Japan tsunami hitting Chilean coast. In: Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), 2012 IEEE International, IEEE, pp 7605–7608, doi:10.1109/IGARSS.2012.6351867

Dzvonkovskaya A, Gurgel KW, Pohlmann T, Schlick T, Xu J (2009a) Simulation of tsunami signatures in ocean surface current maps measured by HF radar. In: OCEANS 2009-EUROPE, IEEE, pp 1–6

Dzvonkovskaya A, Gurgel KW, Pohlmann T, Schlick T, Xu J (2009b) Tsunami detection using HF radar WERA: A simulation approach. In: Radar Conference-Surveillance for a Safer World, 2009. RADAR. International, IEEE, pp 1–6

Dzvonkovskaya A, Figueroa D, Gurgel KW, Rohling H, Schlick T (2011) HF radar observation of a tsunami near Chile after the recent great earthquake in Japan. In: Radar Symposium (IRS), 2011 Proceedings International, IEEE, pp 125–130

Fine I, Rabinovich A, Bornhold B, Thomson R, Kulikov E (2005) The Grand Banks landslide-generated tsunami of November 18, 1929: preliminary analysis and numerical modelling. Mar Geol 215:45–57, doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2004.11.007

Geist E, Lynett P, Chaytor J (2009) Hydrodynamic modeling of tsunamis from the Currituck landslide. Marine Geology 264:41–52

Gica E, Spillane MC, Titov VV, Chamberlin CD, Newman JC (2008) Development of the forecast propagation database for NOAA’s short-term inundation forecast for tsunamis(SIFT). Tech. Rep. NOAA No. OAR PMEL-139, Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, Seattle, WA

Gill EW, Walsh J (2000) Bistatic form of the electric field equations for the scattering of vertically polarized high-frequency ground wave radiation from slightly rough, good conducting surfaces. Radio Science 35:1323–1336

Gill EW, Walsh J (2001) High-frequency bistatic cross sections of the ocean surface. Radio Science 36(6):1459–1475

Gill EW, Huang W, Walsh J (2006) On the development of a second-order bistatic radar cross section of the ocean surface : a high-frequency result for a finite scattering patch. IEEE J Oceanic Engng 31:740–750

Gonzalez FI, Milburn HM, Bernard EN, Newman JC (1998) Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART): Brief overview and status report. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Tsunami Disaster Mitigation, 19–22 January 1998, Tokyo, Japan

Grilli ST, Horrillo J (1997) Numerical generation and absorption of fully nonlinear periodic waves. J Engng Mech 123(10):1060–1069

Grilli ST, Subramanya R (1996) Numerical modeling of wave breaking induced by fixed or moving boundaries. Computational Mechanics 17(6):374–391

Grilli ST, Svendsen I (1990) Corner problems and global accuracy in the boundary element solution of nonlinear wave flows. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements 7(4):178–195

Grilli ST, Watts P (1999) Modeling of waves generated by a moving submerged body. Applications to underwater landslides. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements 23:645–656

Grilli ST, Watts P (2005) Tsunami generation by submarine mass failure Part I : Modeling, experimental validation, and sensitivity analysis. Journal of Waterway Port Coastal and Ocean Engineering 131(6):283–297, doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(2005)131:6(283)

Grilli ST, Skourup J, Svendsen I (1989) An efficient Boundary Element Method for nonlinear water waves. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements 6(2):97–107

Grilli ST, Vogelmann S, Watts P (2002) Development of a 3d Numerical Wave Tank for modeling tsunami generation by underwater landslides. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements 26(4):301–313

Grilli ST, Ioualalen M, Asavanant J, Shi F, Kirby JT, Watts P (2007) Source constraints and model simulation of the December 26, 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Journal of Waterway Port Coastal and Ocean Engineering 133(6):414–428, doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(2007)133:6(414)

Grilli ST, Taylor ODS, Baxter CD, Maretzki S (2009) Probabilistic approach for determining submarine landslide tsunami hazard along the upper East Coast of the United States. Marine Geology 264(1–2):74–97, doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2009.02.010.

Grilli ST, Dubosq S, Pophet N, Pérignon Y, Kirby J, Shi F (2010) Numerical simulation and first-order hazard analysis of large co-seismic tsunamis generated in the Puerto Rico trench: near-field impact on the North shore of Puerto Rico and far-field impact on the US East Coast. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 10:2109–2125, doi:10.5194/nhess-2109-2010

Grilli ST, Harris JC, Tajalli-Bakhsh T, Masterlark TL, Kyriakopoulos C, Kirby JT, Shi F (2013) Numerical simulation of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami based on a new transient FEM co-seismic source: Comparison to far- and near-field observations. Pure and Applied Geophysics 170:1333–1359, doi:10.1007/s00024-012-0528-y

Grilli ST, O’Reilly C, Harris J, Tajalli-Bakhsh T, Tehranirad B, Banihashemi S, Kirby J, Baxter C, Eggeling T, Ma G, Shi F (2015) Modeling of SMF tsunami hazard along the upper US East Coast: Detailed impact around Ocean City, MD. Natural Hazards 76(2):705–746, doi:10.1007/s11069-014-1522-8

Grosdidier S, Forget P, Barbin Y, Guerin CA (2014) HF bistatic ocean Doppler spectra: Simulation versus experimentation. IEEE Trans Geosci and Remote Sens 52(4):2138–2148

Gurgel KW, Dzvonkovskaya A, Pohlmann T, Schlick T, Gill E (2011) Simulation and detection of tsunami signatures in ocean surface currents measured by HF radar. Ocean Dynamics 61(10):1495–1507

Heron ML, Prytz A, Heron SF, Helzel T, Schlick T, Greenslade DJ, Schulz E, Skirving WJ (2008) Tsunami observations by coastal ocean radar. International Journal of Remote Sensing 29(21):6347–6359

Hinata H, Fujii S, Furukawa K, Kataoka T, Miyata M, Kobayashi T, Mizutani M, Kokai T, Kanatsu N (2011) Propagating tsunami wave and subsequent resonant response signals detected by HF radar in the Kii Channel, Japan. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 95(1):268–273

Ioualalen M, Asavanant J, Kaewbanjak N, Grilli ST, Kirby JT, Watts P (2007) Modeling the 26th December 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami: Case study of impact in Thailand. J Geophys Res 112:C07,024, doi:10.1029/2006JC003850

Kawamura K, Laberg JS, Kanamatsu T (2014) Potential tsunamigenic submarine landslides in active margins. Marine Geology 356:44–49

Lipa B, Barrick D, Saitoh SI, Ishikawa Y, Awaji T, Largier J, Garfield N (2011) Japan tsunami current flows observed by HF radars on two continents. Remote Sensing 3(8):1663–1679

Lipa BJ, Barrick DE (1986) Extraction of sea state from HF radar sea echo: Mathematical theory and modeling. Radio Science 21(1):81–100

Lipa BJ, Barrick DE, Bourg J, Nyden BB (2006) HF radar detection of tsunamis. Journal of Oceanography 62(5):705–716

Lipa B, Isaacson J, Nyden B, Barrick D (2012a) Tsunami arrival detection with high frequency (HF) radar. Remote Sensing 4(5):1448–1461

Lipa BJ, Barrick DE, Diposaptono S, Isaacson J, Jena BK, Nyden B, Rajesh K, Kumar TS (2012b) High frequency (HF) radar detection of the weak 2012 Indonesian tsunamis. Remote Sensing 4:2944–2956

Lipa BJ, Parikh H, Barrick DE, Roarty H, Glenn S (2014) High frequency radar observations of the June 2013 US East Coast meteotsunami. Natural Hazards 74:109–122

Longuet-Higgins MS (1963) The effects of non-linearities on statistical distributions in the theory of sea waves. J Fluid Mech 17:459–480

Ma G, Shi F, Kirby JT (2012) Shock-capturing non-hydrostatic model for fully dispersive surface wave processes. Ocean Modeling 43–44:22–35, doi:10.1016/j.ocemod.2011.12.002

Monserrat S, Vilibić I, Rabinovich AB (2006) Meteotsunamis: atmospherically induced destructive ocean waves in the tsunami frequency band. Natural Hazards and Earth System Science 6:1035–1051

Rabinovich AB, Stephenson FE (2004) Long wave measurements for the coast of British Columbia and improvements to the tsunami warning capability. Natural Hazards 32(3):313–343

Shearman E (1986) A review of methods of remote sensing of sea-surface conditions by HF radar and design considerations for narrow-beam systems. Oceanic Engineering, IEEE Journal of 11(2):150–157

Shi F, Kirby JT, Harris JC, Geiman JD, Grilli ST (2012) A high-order adaptive time-stepping TVD solver for Boussinesq modeling of breaking waves and coastal inundation. Ocean Modeling 43-44:36–51, doi:10.1016/j.ocemod.2011.12.004

Stewart RH, Joy JW (1974) Hf radio measurements of surface currents. In: Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts, Elsevier, vol 21, pp 1039–1049

Tappin DR, Watts P, Grilli ST (2008) The Papua New Guinea tsunami of 1998: anatomy of a catastrophic event. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 8:243–266, http://www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/8/243/2008/

Tappin DR, Grilli ST, C HJ, J GR, Thimothy M, T KJ, Shi F, Ma G, Thingbaijamg K, Maig P (2014) Did a submarine landslide contribute to the 2011 Tohoku tsunami ? Marine Geology 357:344–361, doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2014.09.043

Tehranirad B, Harris J, Grilli A, Grilli S, Abadie S, Kirby J, Shi F (2015) Far-field tsunami hazard in the north Atlantic basin from large scale flank collapses of the Cumbre Vieja volcano, La Palma. Pure and Applied Geophysics pp 1–28 (published online 7/21/2015), doi:10.1007/s11069-014-1522-8

ten Brink US, Chaytor JD, Geist EL, Brothers DS, Andrews BD (2014) Assessment of tsunami hazard to the US Atlantic margin. Marine Geology 353:31–54

Ward SN (2001) Landslide tsunami. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth (1978–2012) 106(B6):11,201–11,215

Watts P, Grilli ST, Tappin DR, Fryer GJ (2005) Tsunami generation by submarine mass failure Part II : Predictive equations and case studies. Journal of Waterway Port Coastal and Ocean Engineering 131(6):298–310, doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(2005)131:6(298)

Weber BL, Barrick DE (1977) On the nonlinear theory for gravity waves on the ocean’s surface. J Phys Oceanogr 7(1)

Wyatt LR, et al. (2013) HF radar: Applications in coastal monitoring, planning and engineering. Engineers Australia

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for this study from Diginext Ltd. The reported results only represent the author’s views and interpretations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Directional Wave Number Spectrum

In the present simulations of the radar signal, we will use a standard analytical form of the directional wave energy density spectrum \(\Psi ({\varvec{K}})\), as a function of the wavenumber vector. Assuming a fully developed sea, the spectrum will be constructed based on the one-parameter Pierson–Moskowitz frequency spectrum, which depends solely on wind speed, for instance \(V_{19.5}\) measured at 19.5 m above the sea level, and an analytical angular spreading function.

A commonly used angular spreading function of direction \(\theta \), given the dominant direction of wind waves \(\theta _p\) is,

where \(\xi \in [0,1]\) represents the (asymmetric) fraction of the spectral wave energy associated with waves propagating in the opposite direction and s is an exponent controlling the peakedness of the spreading function. We use \(\xi =0.1\) and \(s=5\) in the present applications. The denominator of Eq. 48 is a normalization factor such that the integral of D over \([0,2\pi ]\) is equal to 1,

The directional PM spectrum used here is thus defined as,

with \(\phi = {\text {atan}}{(K_y/K_x)}\), Phillips’ constant \(\alpha = 0.0081\), and the spectral peak wavenumber is given by,

with \(b=0.74\).

The \(V_{19.5}\) value can be converted into the more standard parameter, \(V_{10}\) (i.e., the wind speed at a 10 m elevation) by representing wind speed as a function of height, V(z), as a classical von Karman logarithmic atmospheric boundary layer profile, which yields the relationship, \(V_{19.5} \simeq V_{10} (19.5/10)^{1/7}\simeq 1.10 V_{10}\). Figure 24 shows an example of a directional PM spectrum computed for \(V_{10}=10\) m/s.

In deep water, the significant wave height corresponding to a given spectrum is obtained as a function of the zero-th moment of the spectral energy density, that is,

For the PM spectrum in Fig. 24, we find \(H_s = 1.71\) m, with \(K_p=0.0493\) m\(^{-1}\) or \(L_p = 127.4\) m, and in deep water (see Eq. 2), \(T_p = 9.04\) s.

Appendix 2: Second-Order Bragg Kernel and Radar Scattering

The second-order Bragg kernel is given by

in which \(\Gamma _e\) is the electromagnetic, and \(\Gamma _h^{\epsilon _1,\epsilon _2}\) the hydrodynamic, coupling coefficient. The latter is defined as

with \(\omega _1=\epsilon _1\sqrt{gK_1}\) and \(\omega _2=\epsilon _1\sqrt{gK_2}\) and the former is defined as

where \({\varvec{u_i}}\) is an unit vector from pointing from the transmitter to the radar cell, \(\Delta \) is the normalized surface impedance, and \(\phi _{bi}\) is the bistatic angle (equal to zero in the monostatic case). See the appendix in Grosdidier et al. (2014) for more details.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grilli, S.T., Grosdidier, S. & Guérin, CA. Tsunami Detection by High-Frequency Radar Beyond the Continental Shelf. Pure Appl. Geophys. 173, 3895–3934 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-015-1193-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-015-1193-8