Abstract

The primitive ruminant genus Iberomeryx is poorly documented, as it is essentially only known from rare occurrences of dental remains. Therefore, the phylogeny and palaeobiology of Iberomeryx remain rather enigmatic. Only two species have been described: the type species I. parvus from the Benara locality in Georgia, and the Western European species I. minor reported from France, Spain, and Switzerland. Iberomeryx savagei from India has recently been placed in the new genus Nalameryx. All these localities are dated to the Rupelian and correspond mainly to MP23 (European mammal reference level). Based on the short height of the tooth-crown and the bunoselenodont pattern of the molars, Iberomeryx has often been considered as a folivore/frugivore. The I. minor remains from Soulce (NW Switzerland) are preserved in Rupelian lacustrine lithographic limestones. One specimen from this locality represents the most complete mandible of the taxon with a partially persevered ramus. Moreover, the unpreserved portion of the mandible left an imprint in the sediment, permitting the reconstruction of the mandible outline. Based on a new description of these specimens, anatomical comparisons and Relative Warp Analysis (24 landmarks) of 94 mandibles (11 fossil and 83 extant) from 31 ruminant genera (10 fossil and 21 extant) and 40 species (11 fossil and 29 extant), this study attempts a preliminary discussion of the phylogeny and the diet of the species I. minor. The results permit to differentiate Pecora and Tragulina on the first principal component axis (first Relative warp) on behalf of the length of the diastema c/cheek teeth, the length of the premolars and the angular process. The mandible shape of I. minor is similar to those of the primitive Tragulina, but it differs somewhat from those of the extant Tragulidae, the only extant family in the Tragulina. This difference is essentially due to a stockier mandible and a deeper incisura vasorum. However, in consideration of the general pattern of its cheek teeth, I. minor as well as possibly Nalameryx should be considered to represent the only known primitive Tragulidae from the Oligocene. Moreover, I. minor should have been a selective browser (fruit and dicot foliage) but, similarly to small Hypertragulidae and Tragulidae, may also have exceptionally consumed animal matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iberomeryx species are small ruminants from the Early Oligocene of Eurasia. The genus, defined by Gabunia (1964), is essentially known by few dental remains and is still poorly documented. Although it has been placed in the infraorder Tragulina, based on its very primitive characteristics, such as bunodont teeth, and an open trigonid and talonid, its suprageneric phylogeny is still under debate. In the opinion of Cope (1888) Iberomeryx belongs to the Xyphodontidae; Stehlin (1914), Carlson (1926), Webb and Taylor (1980), and Sudre (1984) placed it in the Tragulidae; Caroll (1988) in the Moschidae; Gabunia (1964, 1966) and Ghaffar et al. (2006) in the Cervidae; Janis (1987), Métais and Vislobokova (2007), and Métais et al. (2009) in the Lophiomerycidae and Blondel (1997) referred to it as a close relative of Lophiomeryx. In addition, for a long time, most of the specimens now attributed to Iberomeryx were considered to belong to the genus Cryptomeryx (e.g., Schlosser 1886; Gaudant 1979; Sudre 1984). However, Bouvrain et al. (1986) revised the taxonomy of the Oligocene ruminants of the Phosphorites du Quercy (SW France) and reassessed Cryptomeryx as a synonym for Iberomeryx. Among the Iberomeryx species described in the literature, only two are considered as valid: the type species I. parvus from the Benara locality in Georgia (Gabunia 1964, 1966) and the Western European species I. minor from the localities Itardies, Mounayne, Roqueprune 2, and Lovagny in France (Remy et al. 1987; Blondel 1997; Engesser and Mödden 1997), Montalban in Spain (Blondel 1997), and Beuchille, Pré Chevalier, and Soulce in Switzerland (Gaudant 1979; Engesser and Mödden 1997; Becker et al. 2004; this study). These Iberomeryx localities are Rupelian in age and correspond, when dated by small mammals, to MP23 (European mammal reference level; Remy et al. 1987; Schmidt-Kittler 1987; Engesser and Mödden 1997; Schmidt-Kittler et al. 1997; Lucas and Emry 1999; Becker et al. 2004). However, Sudre and Blondel (1996) attributed upper molar remains from La Plante 2 in France (MP22) to I. cf. minor and Antoine et al. (2008) suggested the presence of I. cf. parvus from the Kizilirmak Formation in Turkey (Late Oligocene). These occurrences could be the earliest and the latest records of the genus Iberomeryx, respectively. According to Sudre and Blondel (1996), Iberomeryx matsoui, reported from the German localities Burgmagerbein 8 (MP21; Heissig 1987), Herrlingen 1 (MP22; Heissig 1978; Schmidt-Kittler et al. 1997), and Ehingen 1 (MP23; Heissig 1987) is a synonym for the small Gelocidae Pseudogelocus scotti. The Late Oligocene Asian species, I. savagei, first described as Cryptomeryx savagei (Nanda and Sahni 1990), discovered in the Kargil Formation in India (Blondel 1997; Nanda and Sahni 1998; Guo et al. 2000; Barry et al. 2005), has recently been included in the new genus Nalameryx (Métais et al. 2009). Other European specimens display uncertain affinities with the genus Iberomeryx. Stehlin (1910: 988, fig. 183) assigned small-sized ruminant remains from the old collections of the Phosphorites du Quercy (SW France) to ?Cryptomeryx decedens. The species Cryptomeryx major published by Schlosser (1886) was never figured and the referred material has apparently been lost. From some localities, dated as being younger than MP23, primitive ruminants have been recorded, which were, without confidence, attributed to Iberomeryx: La Ferté Alais (MP24; Blondel 1997), Garouillas (MP25; Sudre 1995), and Mümliswil-Hardberg (MP 26; Engesser and Mödden 1997). These doubtful specimens are in need of revision, as the dental structure of primitive ruminants is very similar and can easily be confused. According to Geraads et al. (1987) and Martinez and Sudre (1995), only the combination of the astragalus shape, the diastema length, the mandible robustness, the p4 structure, and the lower molar shape permit to differentiate between them. In fact, their reassessment could ascribe them to small Gelocidae or Bachitherium vireti from the Early Oligocene.

Regarding the diet of Iberomeryx minor, Sudre (1984) and Becker et al. (2004) proposed a folivore/frugivore trophic mode based on the bunoselenodont structure of cheek teeth. However, I. minor molars and premolars are more bunodont and sharper than those of the extant Tragulina that add significant amounts of animal matter to their diet (Dubost 1984; Sudre 1984; Rössner 2007).

The specimens of I. minor from Soulce (Rupelian, NW Switzerland) are preserved in a lacustrine lithographic bed. Notably, the locality yielded the most complete mandible of this taxon with a partially preserved ramus and an imprint of the missing portion of the mandible. Based on a re-description of these specimens, anatomical comparisons and Relative Warp Analysis (RWA) (24 landmarks) of fossil and extant ruminant mandibles (94 specimens), this study discusses the phylogeny and the diet of the species I. minor.

Geological setting and taphonomy

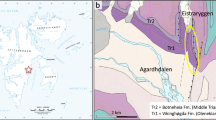

The Iberomeryx specimens were found one kilometre northwest of Soulce (Canton Jura, NW Switzerland; 47°18′39.24″N/7°15′26.28″E). They were discovered by Fleury (1910) in Early Oligocene deposits (Fig. 1). In the Early Oligocene of the north-central Jura Molasse, sedimentation was controlled by multiple incursions of the Rhenish Sea, and three successive transgressive–regressive cycles are known from the Oligocene deposits of the Rhine Graben (Picot 2002; Berger et al. 2005a, b; Picot et al. 2008). In the Porrentruy region (Ajoie district), the first two cycles are recorded, whereas only the second cycle, known as the global Rupelian transgression, generated a contemporaneous incursion in the whole north-central Jura area at the top of NP22 and base of NP23 (ca. MP22; ~32 Ma). A possible ephemeral connection with the Perialpine sea, via a discreet canyon called the Rauraque depression, has been postulated by some authors (e.g., Martini 1990; Berger 1996; Berger et al. 2005a, b). The regression of this second incursion is clearly diachronic, occurring from NP23 to NP24 (ca. top MP22–MP23; ~31 Ma) in a northward and possible westward direction. During this regressive time interval, a deltaic system was established at the southern border of the Rhenish Sea and this marine facies began to prograde northwards (Pirkenseer 2007). The Soulce locality was located within the distal western part of this deltaic environment (Fig. 2).

According to the description of the outcrop (Fleury 1910; Rollier 1910) and in agreement with the geological map (Pfirter et al. 1996; Pfirter 1997) and the recent works on lithostratigraphy (Picot 2002; Berger et al. 2005a), the base of the short section is defined by Paleogene siderolitic fissure-fills and deposits (Bolustone, Ziegler 1956; Bohnerzkonglomerate, Greppin 1855) within and overlaying Mesozoic bedrock. The base of the overlying continental interval is formed by approximately 4 m of marly, calcareous and sandy deposits of the Molasse alsacienne sensu stricto (sensu Picot 2002). The Iberomeryx specimens were preserved in a 95 cm thick lacustrine lithographic limestone bed, extraordinarily rich in plant-, mollusk-, and vertebrate remains. Because of the many articulated fish skeletons (Esox, Umbra, Leuciscus) and two articulated amphibian specimens (Palaeobatrachus cf. diluvianus), this bed can be described as a conservation Lagerstätte.

Mammals are only represented by a few isolated and disarticulated remains of Palaeochoeridae, Anthracotheriidae, and the referred Iberomeryx of this study (Gaudant 1979). The disparate preservation of the articulated skeletons and the isolated remains is a consequence of the particular taphonomic processes involved. By analogy to the model of Messel proposed by Franzen (1985), it is assumed that the lake-dwelling fish and amphibian population died directly within a more or less stagnant freshwater lake. After a short time floating (depending of water depth and temperature), the cadavers would have sunk to the bottom of the lake to be preserved in the form of articulated skeletons. According to Behrensmeyer and Hook (1992), the remains of Iberomeryx are proposed to be the result of occasional flood events, that were responsible for the transport and sorting of terrestrial vertebrate elements and their deposition within a small lake, where they were well preserved in the bottom sediment. The remains of Iberomeryx, although disarticulated, are unworn, excluding a long post mortem transport.

Material, methods and abbreviations

Systematic palaeontology

The referred and morphometric comparison material include the dental remains of Iberomeryx minor from the Soulce, Beuchille and Pré Chevalier localities (Canton Jura, NW Switzerland) and in part the Phosphorites du Quercy localities (old collections and Itardies, SW France; Sudre 1984) from the collection of the Musée jurassien des sciences naturelles (Switzerland), the Naturhistorisches Museum Basel (Switzerland), and the Université des Sciences et Techniques du Languedoc (Montpellier, France). The identifications are based on anatomical feature descriptions, comparative anatomy and biometrical measurements, following the ruminant dental terminology of Gentry et al. (1999). All measurements are given with a precision of 0.1 mm. The biochronological framework is based on the European Land Mammal Ages (ELMA) defined by the succession of European mammal reference levels (MP; Schmidt-Kittler 1987) and the Paleogene geological time scale (Luterbacher et al. 2004).

Relative Warp Analysis

This analysis is based on 11 fossil and 83 extant ruminant mandibles (where available left mandibles) from 31 genera (10 fossil and 21 extant) and 40 species (11 fossil and 29 extant), stored pro parte in the Musée d’histoire naturelle de Fribourg (Switzerland) and the Naturhistorisches Museum Basel (Switzerland), and extracted pro parte from the literature (see Table 1). The number of studied specimens per species varies between one (notably for all extinct species) to 12 (Table 1). The selected material exclusively consists of gender-unspecific, adult specimens. We noted that juvenile specimens do not always bear all adult characteristics and that certain specimens held in captivity at zoos display a strange mandible development. They were, therefore, not included in the analysis. The extant ruminants included in the analysis essentially belong to the three genera of the Tragulina monofamily (Tragulidae) and the two most diversified families of Pecora (Bovidae and Cervidae), completed by some specimens of the Moschidae monogenus (Moschus). Our sampling aims to optimally cover the size range and the feeding categories in each infraorder of extant ruminants (Tragulina and Pecora). The feeding categories are mainly based on those of Janis (1986): (Sb), selective browser (fruits and dicotyledonous herbage foliage selector); (Fl), folivore (at least 90% of dicotyledonous herbage); (Mx), mixed feeder (intermediate feeder with variable diets of dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants) and (Gr), grazer (at least 90% of monocotyledonous grass material). Regarding the fossil sampling, we focused on the Iberomeryx minor specimen of Soulce and other primitive Tragulina and Pecora from the Early Oligocene of Western Europe and North America, and we completed the sampling pool with mandibles of derived taxa from the Neogene.

The mandible specimens were photographed in lateral view with a horizontal orientation of the tooth row, using a camera FinePix S6500fc. The software TpsDig version 1.31, a program for digitizing landmarks and outlines for geometric morphometric analyses developed by Rohlf at the Department of Ecology and Evolution (State University of New York), was used to digitize 24 anatomical landmarks (representing anatomically, geometrically, and linked homologous points) on each digital image representative of the overall mandibular form (including the ramus). The chosen anatomical landmarks, illustrated in Fig. 3, are parameters, which were usually also included in previous studies on mandibular morphology (e.g., Joeckel 1990; Spencer 1995; Perez-Barberia and Gordon 1999; MacFadden 2000; Raia et al. 2010).

Location of anatomical landmarks used for the Relative Warp Analysis on a ruminant mandible (Capreolus capreolus; MHNF 9017-1979). Scale bar 2 cm. 1 posterior part of c; 2 anterior part of p2; 3 anterior part of p3; 4 anterior part of p4; 5 anterior part of m1; 6 anterior part of m2; 7 anterior part of m3; 8 posterior part of m3; 9 projection of 13 on the anterior part of the ramus; 10 maximum of convexity of the coronoid process; 11 maximum of concavity of the coronoid process; 12 projection of 14 on the posterior part of the coronoid process; 13 mandibular incisure; 14 condylar process; 15 maximum of concavity of the ramus; 16 lower part of the angular process; 17 incisura vasorum; 18 projection of 8 on the lower part of the corpus mandibulae; 19 projection of 7 on the lower part of the corpus mandibulae; 20 projection of 6 on the lower part of the corpus mandibulae; 21 projection of 5 on the lower part of the corpus mandibulae; 22 projection of 4 on the lower part of the corpus mandibulae; 23 projection of 3 on the lower part of the corpus mandibulae; 24 projection of 2 on the lower part of the corpus mandibulae

Regarding the geometric morphometric analysis, the method follows that proposed by Querino et al. (2002) and Raia et al. (2010). Traditional morphometric methods use linear distance measurements, which strongly correlate with size. To eliminate the non-shape variation (size) on the landmark configurations, a General Procrustes Analysis was performed (Adams et al. 2004). The coordinates of the mandible landmarks were processed by the least-square method that transforms a landmark configuration, superimposing them (translating, scaling and rotating) on a mean shape (consensus), so that the smallest possible sum of the squares of the distances between the corresponding homologous points results (Monteiro and Reis 1999; Adams et al. 2004). The configurations of the mandible landmarks were combined to analyze only the differences with the consensus.

Thin-Plate Spline function (TPS) was applied to map the landmark configurations represented as deformation grids, where one mandible is deformed or “warped” into another. Shape differences can then be described in terms of deformation-grid differences depicting the objects (Adams et al. 2004). The shape data describing these deformations (partial warps) can be used as shape variables for statistical comparisons of the variation in shape of the mandibles (Table 1). Principal Component Analysis was applied to the partial warp scores resulting in RWA. In order to achieve equal scaling of each regional shape variation, the distortion parameter of Relative warps (principal component axes) was set at α = 0. This procedure is the most suitable for exploratory and taxonomic studies (Rohlf 1993). The superimposing and RWA were performed using the software TpsRelw version 1.46, a program to perform a RWA developed by Rohlf at the Department of Ecology and Evolution (State University of New York). All software of the “TPS” series used in this work is freeware (http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph).

Abbreviations

Conventional abbreviations used in front of the year in the synonymy list follow Matthews (1973): * the work validates the species; . the authors agree on the identification; v the authors have seen the original material of the reference; ? the allocation of the reference is subject to some doubt; non the reference actually does not belong to the species under discussion; pars the reference applies only in part to the species under discussion; no sign the authors were unable to check the validity of the reference. Years in italics indicate a work without description or illustration.

i, lower incisive; c, lower canine; p, lower premolar; m, lower molar; dext., right; sin., left. Sb, selective browser; Fl, folivore; Mx, mixed feeder; Gr, grazer. RWA, Relative Warp Analysis; Rw, Relative warp.

AMNH, American Museum of Natural History (New York, United States); ANSP, Academy of Natural Sciences Philadelphia (United States); BSP, Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie (München, Germany); CI, Chichester Inc. (New York, United States); IPHEP, Institut International de Paléoprimatologie, Paléontologie Humaine: Évolution et Paléoenvironnements, Université de Poitiers (France); MHNF, Musée d’histoire naturelle de Fribourg (Switzerland); MJSN, Musée jurassien des sciences naturelles (Switzerland); MNHN, Musée national d’Histoire naturelle (Paris, France); NMB, Naturhistorisches Museum Basel (Switzerland); USTL, Université des Sciences et Techniques du Languedoc (Montpellier, France).

Systematic palaeontology

-

Order Cetartiodactyla Montgelard, Catzeflis and Douzery 1997

-

Suborder Ruminantia Scopoli 1777

-

Infraorder Tragulina Flower 1883

-

Family Tragulidae Milne-Edwards 1864

-

Genus Iberomeryx Gabunia 1964

-

Type species—Iberomeryx parvus Gabunia 1964, from Benara (Georgia), Early Oligocene (MP23; Lucas & Emry 1999).

-

Other species referred to the genus—Iberomeryx minor (Filhol 1882), Early Oligocene of Western Europe.

-

Iberomeryx minor (Filhol 1882)

-

Synonymy (updated from Sudre 1984)

non | 1877 | Lophiomeryx gaudryi Filhol: 447, figs. 279–280. |

* | 1882 | Bachitherium minor—Filhol: 138. |

pars | 1886 | Cryptomeryx gaudryi—Schlosser: pl. II, figs. 13–14. |

v | 1910 | Cryptomeryx gaudryi—Fleury: 277. |

v | 1914 | Cryptomeryx gaudryi—Stehlin: 184. |

1926 | Cryptomeryx gaudryi—Carlson: 69. | |

1962 | Cryptomeryx—Friant: 114. | |

1966 | cf. Cryptomeryx gaudryi—Palmowski and Wachendorf: 241, pl. 15, fig. 7. | |

1967 | Cryptomeryx—Friant: 96. | |

1973 | Bachitherium ? sp.—Bonis et al.: tab. 2(4). | |

? | 1978 | Cryptomeryx cf. gaudryi—Heissig: 271, tab. 4. |

v | 1979 | Cryptomeryx gaudryi—Gaudant: 889, figs. 17–20. |

1980 | Cryptomeryx—Webb and Taylor: 124. | |

v | 1984 | Cryptomeryx gaudryi—Sudre: 6, figs 1–9. |

* | 1986 | Iberomeryx minor—Bouvrain et al.: 102, fig. 2. |

. | 1987 | Iberomeryx minor—Geraads et al.: 44, figs. 16, 27, 36. |

? | 1987 | Iberomeryx matsoui—Heissig: 108, fig. 6. |

v | 1996 | Iberomeryx minus—Sudre & Blondel: 178, tab. 1. |

v | 1997 | Iberomerx minus—Blondel: 584, tabs. 8–9. |

v. | 2004 | Iberomeryx minor—Becker et al.: 184, fig. 5. |

2007 | Iberomeryx minus—Métais and Vislobokova: 195. |

Holotype—fragmentary mandible with tooth row p3–m3 dext. (MNHN QU4234; Bouvrain et al. 1986: 103, fig. 2). Filhol (1882) first described this type as a tooth row p2–m3 dext., but p2 has been lost.

Type locality—Unknown (from the old collections of the Phosphorites du Quercy, SW France).

Stratigraphical range—Early Oligocene, mainly MP23 sites in Western Europe: Soulce, Beuchille and Pré Chevalier in Switzerland; Itardie, Mounayne, Roqueprune 2 and Lovagny in France; and Montalban in Spain (Gaudant 1979; Sudre 1984; Remy et al. 1987; Blondel 1997; Becker et al. 2004).

Referred material (Fig. 4)—NMB Sc.118 (Gaudant 1979: 889), tooth row with m1–m3 dext. and nearly complete mandible with p2–p4 sin. from the Soulce locality (NW Switzerland).

Iberomeryx minor specimens (NMB Sc.118) from the lacustrine lithographic limestone bed of Soulce (Early Oligocene, north-central Jura Molasse, NW Switzerland). Scale bars 1 cm. Tooth row with m1–m3 dext., lingual view photograph (a1, b2), occlusal view photograph (b1); nearly complete mandible with p2–p4 sin., labial view photograph (a2, c1), labial view drawing (c2)

Comparison material (Fig. 5)—MJSN BEU001–409 (old number BEU-700-J1; Becker et al. 2004: 184, fig. 5), fragmentary tooth row with m1–m3 dext. from the Beuchille locality (NW Switzerland); MJSN BEU001–410 (new material), fragmentary mandible with p4 dext. from the Beuchille locality (NW Switzerland); MJSN BEU001–411 (new material), fragmentary mandible with m1–m2 dext. from the Beuchille locality (NW Switzerland); MJSN PRC004–159 (new material), fragmentary mandible with p4–m3 dext. From the Pré Chevalier locality (NW Switzerland); NMB Q.B.32 (Sudre 1984: 11, fig. 5), fragmentary mandible with p3–m3 sin. from the older collection of the Phosphorites du Quercy (SW France).

Comparison material. Iberomeryx minor specimens from the localities Pré Chevalier and Beuchille (Early Oligocene, north-central Jura Molasse, NW Switzerland) and from the Phosphorites du Quercy (old collections, SW France). Scale bar for all figures 1 cm. a Pré Chevalier (MJSN PRC004–159), fragmentary mandible with p4–m3 dext., labial view (1), occlusal view (2), lingual view (3); b Phosphorites du Quercy (NMB Q.B.32), fragmentary mandible with p3–m3 sin., labial view (1), occlusal view (2), lingual view (3); c Beuchille (MJSN BEU001–409), fragmentary tooth row with m1–m3 dext., occlusal view (1), lingual view (2); d Beuchille (MJSN BEU001–410), fragmentary mandible with p4 dext., lingual view; e Beuchille (MJSN BEU001–411), fragmentary mandible with m1–m2 dext., occlusal view (1), labial view (2), lingual view (3)

Emended diagnosis—Small-sized ruminant with upper molars possessing the following combination of characters: well-marked parastyle and mesostyle in colonnette shape; strong paracone fold; metacone fold absent; metastyle absent; unaligned external walls of metacone and protocone; strong postprotocrista stopping up against the anterior side of the praehypocrista; continuous lingual cingulum, stronger under the protocone. Lower dental formula is primitive (3–1–4–3) with unmolarized premolars. Tooth c is adjacent to i3. Tooth p1 is one-rooted, reduced and separated from c and p2 by a short diastema. Premolars have a well-developed protoconulid. Teeth p2–p3 display a distally bifurcated hypoconid, forming a posterior fossette. Tooth p3 is the largest premolar. Tooth p4 displays no metaconid and a large posterior fossette nearly closed by unfused lingual and labial cristids. Regarding the lower molars, the trigonid and talonid are lingually open with a trigonid more tapered than the talonid. The anterior fossette is open, due to a forward orientation of the praeprotocristid and an anterior protoconulid. The postprotocristid is oblique, without Palaeomeryx fold. Postprotocristid, postmetacristid and praeentocristid are fused and Y-shaped. Protoconid and metaconid display a weak Tragulus fold and a well-developed Dorcatherium fold, respectively. The mandible displays an angular convex ventral profile, a marked incisura vasorum, a strong mandibular angular process, a vertical ramus, and a stout condylar process. It differs from I. parvus by larger trigonids on the lower molars and a smaller protoconulid and a larger posterior fossette on p4.

Description

The referred specimens from Soulce (NMB Sc.118; Fig. 4) are composed of a part of a tooth row sin. bearing m1–3 (Fig. 4a1, b1–b2) and a nearly complete mandible dext. bearing p2–4 as well as its counterpart with an imprint of m1–3 (Fig. 4a2, c1–c2). Both tooth rows have a similarly advanced degree of wear and could belong to the same individual. All measurements are summarized in Table 2.

Tooth p1 is one-rooted, the other premolars are two-rooted, weakly differentiated and only display a very slight molarization on p3–4. The protoconulid of p2–3 is completely worn. On p3–4 and the molars, the anterior labial cingulid is well developed (slightly damaged on m1–3 due to the preparation of the specimen). Teeth p2–3 have the same occlusal pattern: elongated outline (p3 is of the same dimension as m1) with the presence of a hypoconid (absent on p4) and a closed basin backward of the latter. On p4, the metaconid is absent and the protoconulid is slightly oblique and separated from the protoconid by a deep groove.

Lower molar cuspids are bunoselenodont, high, and quite tapered (Fig. 4b2). The protoconid is spherical and displays a shallow and broad groove forming a weak Tragulus fold; the Paleomeryx fold is absent. The metaconid displays a deep incisure on its posterior part, characteristic of the Dorcatherium fold, forming an open buckle on the lingual side of the crown. The exostylid is always present between the protoconid and the hypoconid. The entoconid is well rounded on its posterior part, without postentocristid, giving a spherical aspect to the proximal half of the lower molars. The anterior part of the entoconid is tapered, with a relatively striking praeentocristid that joins the postmetacristid and forms a keel as described by Sudre (1984). This keel is lingually slightly concave, but does not form a real Zhailimeryx fold. The postmetacristid, postprotocristid and praeentocristid are converging and Y-shaped. The anterior valley is open forwards; the praehypocristid and the posthypocristid are angular with a right dihedron; the talonid is broader than the trigonid. Tooth m1 is trapezoid and m2 is rectangular. Following the same pattern as p4, the anterior part of the trigonid on m1 is elongated in front of the metaconid by a strong protoconulid. The latter is decreasingly well developed on m2–3. The entoconulid on m1–2 is weakly developed and separated from the entoconid by a groove. A posterior cingulid surrounds the base of the hypoconulid on m3 (Fig. 4b1).

The mandible outline is stout. Its anterior part is fragmented, but nevertheless displays a double foramen mentale located under the short diastema p1/2. The corpus mandibulae presents an angular convex ventral profile. The incisura vasorum is rounded, well marked, and located under the anterior border of the ramus. The latter is almost vertical. The angular, coronoid and condylar processes are only partially preserved, nonetheless some observations can be noted: the angular process is high, large and smoothly rounded (relatively large and with constant radius); the coronoid process is marked; the condylar process, the outline of which can be reconstructed due to the association of the preserved fossil (head) and imprint (neck), is very stout (Fig. 4c1–c2).

Taxonomical affinities

Table 3 summarizes the morphological comparisons between primitive and Miocene ruminants (Tragulina and Pecora) and extant tragulids. The specimens from Soulce (NMB Sc.118; Fig. 4) were first mentioned by Stehlin (in Fleury 1910) and first described by Gaudant (1979) as Cryptomeryx gaudryi. They correspond to a very small-sized ruminant, smaller than the European Lophiomeryx and Prodremotherium species. The diastema between p1/p2 observed on the nearly complete mandible (Fig. 4a2, c1–c2) is proportionally shorter than those of the Western European Bachitherium, North American Leptomeryx, and Eurasiatic Lophiomeryx. The incisura vasorum of the mandible is similar to those of I. minor (Fig. 5b1, b3) from the Phosphorites du Quercy (SW France) and stronger than those of Bachitherium and Leptomeryx. Moreover p2–3 differ from Bachitherium by the presence of a hypoconid and p4 differs from the Hypertragulidae (Nanotragulus), Leptomerycidae (Leptomeryx), Lophiomerycidae (Lophiomeryx, Krabimeryx, Zhailimeryx), Gelocidae (Gelocus, Prodremotherium), and modern Pecora (Dremotherium, Procervulus) by the absence of a metaconid (Geraads et al. 1987; Guo et al. 2000; Métais et al. 2001). The lower molars of Lophiomeryx as well as of the Hypertragulidae (Nanotragulus), Leptomerycidae (Leptomeryx), Bachitheriidae (Bachitherium), and Pecora (Gelocus, Prodremotherium, Dremotherium, Procervulus) also differ by the absence of the typical Y-configuration and, contrary to Blondel (1997), also by the absence of a Dorcatherium fold (variable in Leptomeryx). The specimens from Soulce (Fig. 4) exhibit the same dental pattern (e.g., hypoconid on p2–3, metaconid absent on p4 as well as protoconulid present, open trigonid and talonid, a strong Dorcatherium fold, and Y-configuration on lower molars) as Archaeotragulus, Iberomeryx (Fig. 5), Nalameryx, Dorcatherium, and extant Tragulidae. According to the description of Métais et al. (2001), Archaeotragulus teeth bear many characters that differ from the Soulce specimens (e.g., larger size, p4 of the same dimension as m1, lower molar praehypocristid less-lingually oriented; see Tables 2, 3). Dorcatherium shows teeth more bunodont and larger in size (Sudre 1984). Most modern Tragulidae (e.g., Tragulus, Moscholia) have derived lower premolars with a transformation of the posterior basin to a cristid, that gives the teeth a blade shape. The morphometric data (Table 2) is very similar to that of Iberomeryx minor from the Phosphorites du Quercy (SW France) and from the Jura Molasse (NW Switzerland), but also to that of the small species of the genus Nalameryx (N. savagei) from Kargil (India) and the Bugi Hills (Pakistan). However, the lower molars of N. savagei differ because of the presence of a more developed Tragulus fold and an oblique less-lingually oriented cristid (Métais et al. 2009).

In this study the emended diagnosis of I. minor is based on dental and mandible morphology, such as a well-developed Dorcatherium fold, a large posterior fossette closed by unfused lingual and labial cristids on p4 and a marked incisura vasorum. Therefore, the referred specimens from Soulce (Fig. 4) as well as those from Beuchille (Fig. 5c1–c2, d, e1–e3) and Pré Chevalier (Fig. 5a1–a3) can be confidently assigned to I. minor.

Relative Warp Analysis

The 24 anatomic landmarks generated 44 axes (Rw’s) for each ruminant mandible. The results of the Rw’s, using shape components, permitted the distinction of different groups of ruminants based on the total difference of the mandible shape. Rw1 explained 28.9% and Rw2 27.8% respectively. This means that 56.6% of shape variance (Fig. 6), can be explained without the use of other Rw’s. On Rw1, elongation of the premolars is positively associated with the enlargement of the condylar process and the forward projection of the ramus (see shape deformation grids in Fig. 6.1). On Rw2 the diastema c/cheek teeth elongation, the shallowing-up corpus mandibulae and the development of the incisura vasorum occur in a positive variance (see shape deformation grids in Fig. 6.1).

RWA for distortion parameter α = 0 of ruminant mandibles obtained from 11 fossil specimens (Bison antiquus, Dicrocerus elegans, Dremotherium feignouxi, Dremotherium guthi, Gelocus villebramarensis, Procervulus dichotomus, Brachitherium cf. curtum, Dorcatherium naui, Iberomeryx minor, Leptomeryx evansi, Nanotragulus loomsi; see Table 2) and 83 extant specimens (see Table 2). 1 Shape deformation grids representing the mean shape (consensus) and the maximum values of the two-first Relative warps (Rw’s). 2 Scatter plots of the first versus the second Rw with taxonomic characterization. The A axis indicates the shape variation of the mandible “warped” from the mean shape (consensus) into the maximum positive deviations in the axis of Rw1; the B axis the shape variation of the mandible “warped” from the mean shape (consensus) into the maximum negative deviations in the axis of Rw1; the C axis the shape variation of the mandible “warped” from the mean shape (consensus) into the maximum positive deviations in the axis of Rw2; and the D axis the shape variation of the mandible “warped” from the mean shape (consensus) into the maximum negative deviations in the axis of Rw2. 3 Indication of the diet. A, B, C, and D axes as in 2

Both Rw1 and Rw2 are informative from both a phylogenetic (Fig. 6.2) and ecologic (Fig. 6.3) perspective. Theses two Rw’s permit the discrimination of the Ruminantia infraorders, Tragulina and Pecora. The group characters of extant Tragulina (see shape deformation grids in Fig. 6.1) are a weak incisura vasorum, a vertical ramus, a short coronoid process inclined backwards, a stout condylar process, a rather short diastema c/cheek teeth, and enlarged premolars (p3 being the largest). The extant Tragulina plot in the negative-values domain of both Rw1 and Rw2 (Fig. 6.2). Contrarily, the Pecora (Cervidae, Moschidae, Bovidae) mainly plot as positive Rw1 values, and negative and positive Rw2 values. The Bovidae values are preferentially but not exclusively located in the negative domain while the Cervidae values plot preferentially in the positive domain and Moschidae are located in the mixed area between Cervidae and Bovidae (Fig. 6.2). The Pecora mandible shape is characterized by a strong incisura vasorum, a ramus inclined backwards, a developed coronoid process, a slender condylar process, a long diastema c/cheek teeth, and shortened premolars (see shape deformation grids in Fig. 6.1). However, there is also some feeding-habit dependant variation of the mandible shape (Fig. 6.3).

Grazers plot exclusively in the quadrant defined by positive Rw1 values and negative Rw2 values. In the lower half of the graph, defined by negative Rw2 values and positive Rw1 values, a trend from grazers over mixed feeder to folivore Bovidae is discriminated with decreasing Rw1 values. Selective browser Tragulidae are characterized by negative values of both Rw1 and Rw2. On the other hand, Cervidae with different feeding adaptations, Moschidae and selective browser Bovidae mainly have positive Rw2 values (Fig. 6.3).

Extinct taxa present two types of cases. Middle Miocene to Pleistocene Ruminantia plot together with their extant relative family (e.g., Dorcatherium naui within extant Tragulidae; Fig. 6.2–3), whereas peculiar shapes occur among more primitive extinct groups (e.g., primitive Tragulina; Fig. 6.2–3).

Discussion

Biostratigraphy

Figure 7 illustrates a biostratigraphic synthesis of the Oligocene Eurasian Iberomeryx. According to Sudre and Blondel (1996) and Blondel (1997), the earliest record of Iberomeryx can be dated to the European Mammal reference level MP22 thanks to a few specimens assigned to I. cf. minor from La Plante 2. On another hand, the latest record could be the specimens of I. cf. parvus provisionally identified by Antoine et al. (2008) from the Late Oligocene Kizilirmak Formation in Turkey. All other well-dated localities yielding I. minor can be assigned to the level MP23 (Montalban, Itardies, Monayne, Roqueprune 2). Lucas and Emry (1999) state that the age of the Benara locality, which is the type locality of I. parvus, also corresponds to the level MP23. The Swiss I. minor localities remain poorly dated. At the Beuchille locality, the upper 15 m of the section is dated by Blainvillimys avus and corresponds to MP24 (Vianey-Liaud and Michaux 2003; Becker et al. 2004). However, I. minor remains were discovered at the base of the section, just above a level yielding Pseudocricetodon cf. montalbanensis (MP23 after Brunet and Vianey-Liaud 1987 and Aguilar et al. 1997). Based on lithostratigraphy, the Pré Chevalier locality can be correlated with Beuchille and is probably of the same age. The Iberomeryx minor specimens from Soulce were recovered from the Calcaires inférieurs Formation. This lacustrine formation is laterally equivalent to other formations of the Swiss Jura Molasse (e.g., Calcaires de Moutier), and seems to be restricted to the Rupelian. Gaudant (1979) assigned an Oligocene age younger than MP21 to the bone bed of Soulce without confidence, because of the absence of Iberomeryx in Ronzon (MP21, France). Considering these biostratigraphic data, an age older than MP22 and even older than MP23 for I. minor seems very unlikely. To date, except for the I. cf. minor specimens of La Plante 2, no findings argument against its first occurrence within the European Mammal reference level MP23. Nonetheless, a slightly older or younger age can, at present, not be excluded with confidence.

Synthesis of the Oligocene occurrences of Eurasian Iberomeryx. The chronostratigraphy and Mammal reference levels are based on Luterbacher et al. (2004). The time interval (ca. 33.6–33.4 Ma) of the “Grande Coupure” event (Stehlin 1910) is based on the high-resolution stratigraphy in the Belgian Basin after Hooker et al. (2004, 2009). The biochronostratigraphical ranges are revised in accordance with Remy et al. (1987), Sudre and Blondel (1996), Blondel (1997), Lucas and Emry (1999), Vianey-Liaud and Michaux (2003), Becker et al. (2004), and Antoine et al. (2008)

Phylogenetic implications

Primitive Pecora and Tragulina mandible shapes differ slightly from those of their respective extant relatives (Fig. 6). The results of the RWA do not permit the separation of Iberomeryx minor from other Oligocene Tragulina Hypertragulidae (Nanotragulus loomsi), Leptomerycidae (Leptomeryx evansi), and Bachitheriidae (Bachitherium curtum) on behalf of the characteristics of its mandible shape. The primitive Tragulina form a homogenous group plotting between extant Tragulina and Bovidae and characterized by a mandible shaped similarly to that of a Suoid (short diastema c/cheek teeth, enlarged vertical ramus, corpus mandibularis and angular process, and p1 separated from other premolars). The mandible of the primitive Tragulina represents the rather basic shape throughout Tragulina evolution. Gelocus villebramarensis from the Early Oligocene has a shorter diastema and more elongated premolars with a relatively larger corpus mandibularis relative to extant Pecora, and can possess a p1 either isolated or adjacent to the premolars. Tooth p1 is not separated from the other premolars in Dremotherium and is absent in other Pecora. This evolutionary trend in p1 is associated with an elongation of the diastema c/cheek teeth. Even if Gelocus resembles “tragulid-like” taxa more than extant Pecora, it clearly has a more elongated diastema c/cheek teeth and a more slender general mandible shape than Oligocene Tragulina. In the genus Dremotherium (Late Chattian to Aquitanian), premolars become shorter and the corpus mandibularis becomes more slender. Finally, Miocene Procervulus dichotomus and Dicrocerus elegans cannot be distinguished from the extant Cervidae.

Our results support that phylogeny contributes to shape variation in ruminant mandibles. However, a confident assignment of I. minor to a Tragulina family is only possible if the overall set of its morphological and morphometrical characteristics is taken into account. Janis (1987), Métais and Vislobokova (2007), and Métais et al. (2009) considered Iberomeryx to belong to the Lophiomerycidae, and Blondel (1997) to be close to Lophiomeryx. Like Lophiomeryx, Iberomeryx has an open trigonid and an open talonid on the lower cheek teeth and an angle between the trochleas of the astragalus (Brunet and Sudre 1987). These dental features are also present in the primitive taxa Krabimeryx, Archaeotragulus (Métais et al. 2001), and Zhailimeryx (Guo et al. 2000). Additionally, the extant Tragulidae, Bachitherium or the Anoplotherioidea (a sister group of the Ruminantia) do not possess aligned trochleas. The aligned trochleas are a characteristic feature of the derived Ruminantia such as the Pecora (Martinez and Sudre 1995). Moreover, Iberomeryx differs from Lophiomeryx because of the astragalus articular facet with the cubo-navicular bone that does not bear a crest (Brunet and Sudre 1987; Martinez and Sudre 1995). The metatarsal bones of Lophiomeryx are not fused (Geraads et al. 1987; Blondel 1997) and, on the upper molars, the metacone and paracone are aligned contrary to Bachitherium (Ferrandini et al. 2000) and the Tragulidae. The pattern of the lower cheek teeth of Iberomeryx and Lophiomeryx is totally different, although the trigonid and talonid are open in these two taxa. The open trigonid in Iberomeryx is accounted for by the presence of a small protoconulid in front of the protoconid, whereas it is due to the anterior orientation of the praeprotocristid in Lophiomeryx. The lower molars of Iberomeryx bear a Y-shape on the cristids and a deep Dorcatherium fold on a well-individualised metaconid. These characteristic features are known from Miocene Tragulidae. The Dorcatherium fold is absent in Lophiomeryx and the metaconid, which is simple, thin, and conical, is located in the axis of the postprotocristid (Brunet and Sudre 1987; Janis 1987). Even if Iberomeryx shares many primitive features with Lophiomeryx, there are evident differences in the features (e.g., Dorcatherium fold, Tragulus fold, general premolar shape) that relate it rather to the Tragulidae than to the Lophiomerycidae as suggested by Stehlin (1914), Carlson (1926), Webb and Taylor (1980), and Sudre (1984).

Rössner (2007) and Sánchez et al. (2010) only considered Archaeotragulus from the Eocene, Afrotragulus, Dorcatherium, Dorcabune, Siamotragulus, Yunannotherium from the Neogene and the three extant genera (Tragulus, Hyemoschus, Moscholia) to be representatives of the Tragulidae. The Paleogene fossil record of tragulids is extremely poor and Oligocene tragulid evolution lacks fossil evidence (Gentry et al. (1999); Métais et al. 2009). Without more data, even the affiliation of Archaeotragulus to the Tragulidae remains debatable (Métais et al. 2009). Nalameryx savagei shows morphological and morphometrical features very similar to those of Archaeotragulus and Iberomeryx. The two species of Nalameryx (N. savagei, N. sulaimani) have been placed in the Lophiomerycidae due to an open trigonid on the lower molars, the absence of a praemetacristid and an antero-lingual orientation of the praeprotocristid (Métais et al. 2009). They share these characteristic features with the Tragulidae. Nalameryx genus could thus also be considered as a representative of the Tragulidae from the Oligocene.

Palaeodiet

The RWA of this study reveals progressive trends in the shape of the mandible of extant and some fossil ruminants related to their feeding habits (selective browser, folivore, mixed feeder and grazer). The only evident anomaly in the RWA concerns the position of the small, South American Cervidae Mazama nemorivaga among the mixed feeder (-folivore) cervids (Fig. 6.3). This species is known to feed on fruits and leaves. Its recent ancestor was a larger leaf eater ruminant (Eisenberg 2000), which later became a small sized frugivore/folivore. This might explain the position of M. nemorivaga near the folivore cervids, contrariwise to the position of Pudu puda, which is also a small, South American, extant frugivore/folivore Cervidae. Dwarfism and fruit feeding seem to have appeared independently and at different times in these two taxa (Eisenberg 2000).

Since the Middle Miocene, the feeding-habit related mandible shapes have been similar to those of extant ruminants. In the primitive ruminants, this relation is not evident. The mandible shapes of primitive Tragulina do not permit to differentiate between different feeding adaptations (Fig. 6.3). However, the primitive Tragulina analysed in this study form a distinctive group. Leptomeryx evansi was a C3-browser sensu lato (Wall and Collins 1998; Zanazzi and Kohn 2008), comparable to extant Pudu puda and the genus Tragulus, which both are selective browsers (Wall and Collins 1998; see Table 1). The small Hypertragulidae Nanotragulus loomsi fed on soft food such as fruits or leaves, and possibly insects (Métais and Vislobokova 2007). According to a microwear study of Blondel (1996), Bachitherium curtum was a selective browser feeding on leaves and fruits. In addition, Iberomeryx minor possessed a large coronoid process, which indicates that the temporalis muscle and therefore the orthal retraction phase of the chewing cycle (food acquisition phase of mastication) were important similar as in Leptomeryx evansi and browsers sensu lato (Wall and Collins 1998). The angular process has nearly the same shape within primitive and extant Tragulina (quiet wide masseteric fossa). Cheek teeth are brachyodont, but with sharper and higher bunoselenodont cusps than in extant Tragulidae, which are nearly of same size.

Within mammalian herbivores, the total metabolic requirement increases with weight but with a decreasing rate. Large forms require more total energy, but small forms require more energy with respect to their weight (Kleiber 1975). Regarding the same metabolism and the same diet, the retention time is shorter for small animals. Fruits contain proportionally less cell wall (hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin) than leaves and grass (Demment and van Soest 1985). Thus, a heavier animal can develop a diet including lower-quality food (more cell wall, less energy). Hope (1977) interpreted the negative correlation between fermentation rate and increasing body mass as a decrease in the proportion of dicotyledons with respect to monocotyledons in the diet. Such a categorisation of diets in function of the body mass can also be observed in ruminants (Bodmer 1990). Small-sized Tragulidae can eat fruits and significant amounts of animal matter such as insects, crabs, carrion and fish (Sudre 1984; Métais and Vislobokova 2007; Rössner 2007). That is why Iberomeryx minor should be selective browser, and could also eat some insects, similar to extant Tragulidae.

Conclusions

Both phylogeny and feeding adaptation contribute to the variation in the shape of ruminant mandibles. However, without taking into account other morphological and morphometrical characteristics, notably the dental structure, our RWA does not supply sufficient information to discuss taxonomy higher than at family level. Furthermore confident feeding category discrimination, more advanced than grazer versus browser, cannot be achieved. Only the combined fundamental study of comparative anatomy and RWA permit our taxonomic and ecologic deductions on the species Iberomeryx minor. The latter is a primitive ruminant characteristic for the Rupelian and probably restricted to the European mammal reference level MP23. Iberomeryx minor as well as possibly Nalameryx should be considered as the only Tragulidae from the Oligocene and thus the missing link between the enigmatic Eocene Asiatic “tragulid-like” Archaeotragulus and the classical Neogene and extant tragulids (Afrotragulus, Dorcatherium, Dorcabune, Siamotragulus, Yunannotherium, Tragulus, Hyemoschus, Moscholia). Moreover, Iberomeryx minor should be considered as a selective browser, similar to extant Tragulidae, which also fed on animal matter.

References

Adams, D. C., Rohlf, F. J., & Slice, D. E. (2004). Geometric morphometrics: Ten years of progress following the “revolution”. Italian Journal of Zoology, 71, 5–16.

Aguilar, J.-P., Augustí, J., Alexeeva, N. V., Antoine, P.-O., Antunes, M. T., Archer, M., et al. (1997). Syntheses and correlation tables. In J.-P. Aguilar, S. Legendre, & J. Michaux (Eds.), Actes du Congrès BiochroM’97. Mémoires et Travaux de l’École pratique des Hautes Études (Vol. 21, pp. 769–805). France: Institut de Montpellier.

Antoine, P.-O., Karadenizli, L., Saraç, G., & Sen, S. (2008). A giant rhinocerotoid (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Late Oligocene of north-central Anatolia (Turkey). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 152, 581–592.

Barry, J. C., Cote, S., MacLatchy, L., Lindsay, E. H., Kityo, R., & Rahim Rajppar, A. (2005). Oligocene and Early Miocene Ruminants (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from Pakistan and Uganda. Palaeontologica Electronica, 8, 1–29.

Becker, D., Lapaire, F., Picot, L., Engesser, B., & Berger, J.-P. (2004). Biostratigraphie et paléoécologie du gisement à vertébrés de La Beuchille (Oligocène, Jura, Suisse). Revue de Paléobiologie, 9, 179–191.

Behrensmeyer, A. K., & Hook, R. W. (1992). Paleoenvironmental contexts and taphonomic modes. In A. K. Behrensmeyer, J. D. Damuth, W. A. DiMichele, R. Potts, H. D. Sues, & S. L. Wing (Eds.), Terrestrial ecosystems through time: Evolutionary paleoecology of terrestrial plants and animals (pp. 15–136). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berger, J.-P. (1996). Cartes paléogéographique-palinspastiques du basin molassique suisse (Oligocène inférieur–Miocène moyen). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen, 202, 1–44.

Berger, J.-P., Reichenbacher, B., Becker, D., Grimm, M., Grimm, K., Picot, L., et al. (2005a). Paleogeography of the Upper Rhine Graben (URG) and the Swiss Molasse Basin (SMB) from Eocene to Pliocene. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 94, 697–710.

Berger, J.-P., Reichenbacher, B., Becker, D., Grimm, M., Grimm, K., Picot, L., et al. (2005b). Eocene-Pliocene time scale and stratigraphy of the Upper Rhine Graben (URG) and the Swiss Molasse Basin (SMB). International Journal of Earth Sciences, 94, 711–731.

Blondel, C. (1996). Les ongulés à la limite Eocène/Oligocène et au cours de l’Oligocène en Europe occidentale: Analyses faunistiques, morpho-anatomiques et biogéochimiques (d 13 C, d 18 O). Implications sur la reconstitution des paléoenvironnements (119 pp). Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Montpellier II, France.

Blondel, C. (1997). Les ruminants de Pech Desse et de Pech du Fraysse (Quercy, MP 28); évolution des ruminants de l’Oligocène d’Europe. Geobios, 30, 573–591.

Blondel, C. (1998). Le squelette appendiculaire de sept ruminants oligocènes d’Europe, implications paléoécologiques. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, 326, 527–532.

Bodmer, R. D. (1990). Ungulate frugivores and the browser-graser continuum. Oikos, 57, 319–325.

Bouvrain, G., Geraads, D., & Sudre, J. (1986). Révision taxonomique de quelques ruminants oligocènes des phosphorites du Quercy. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, 302(II(2)), 101–104.

Brunet, M., & Jehenne, Y. (1976). Un nouveau ruminant primitif des molasses oligocènes de l’Agenais. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 7, 1659–1664.

Brunet, M., & Sudre, J. (1987). Evolution et systematique du genre Lophiomeryx POMEL 1853 (Mammalia, Artiodactyla). Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 10, 225–242.

Brunet, M., & Vianey-Liaud, M. (1987). Mammalian Reference Levels MP21–30. Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 10, 30–31.

Carlson, A. (1926). Über die Tragulidae und ihre Beziehungen zu den übrigen Artiodactyla. Acta Zoologica, 7, 69–100.

Caroll, R. L. (1988). Vertebrate paleontology and evolution (p. 698). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Cope, E. D. (1888). The Artiodactyla. The American Naturalist, 22, 1079–1095.

Costeur, L., & Legendre, S. (2008). Mammalian communities document a latitudinal environmental gradient during the Miocene Climatic Optimum in Western Europe. Palaios, 23, 280–288.

Demment, M. W., & van Soest, P. J. (1985). A nutritional explanation for body-size patterns of ruminant and nonruminant herbivores. The American Naturalist, 125, 641–672.

Dubost, G. (1984). Comparison of the diets of frugivorous forest ruminants of Gabon. Journal of Mammalogy, 65, 298–316.

Eisenberg, J. F. (2000). The contemporary Cervidae of Central and South America. In E. S. Vrba & G. B. Schaller (Eds.), Antilopes, deer, and relatives: Fossil record, behavioral ecology, systematics and conservation (pp. 189–202). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Engesser, B., & Mödden, C. (1997) A new version of the biozonation of the Lower Freshwater Molasse (Oligocene, Agenian) of Switzerland and Savoy on the basis of fossil mammals. In J.-P. Aguilar, S. Legendre, & J. Michaux (Eds.), Actes du Congrès BiochroM’97. Mémoires et Travaux de l’Ecole pratique des Hautes Etudes (Vol. 21, pp. 581–590). France: Institut de Montpellier.

Ferrandini, M., Ginsburg, L., Ferrandini, J., & Rossi, P. (2000). Présence de Pomelomeryx boulangeri (Artiodactyla, Mammalia) dans l’Oligocène supérieur de la région d’Ajaccio (Corse): étude paléontologique et conséquences. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, 331, 675–681.

Filhol, H. (1882). Découverte de quelques nouveaux genres de mammifères fossiles dans les dépôts de phosphate de chaux de Quercy. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, 94, 138–139.

Fleury, E. (1910). Tertiaire du vallon de Soulce. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 11, 275–278.

Fortelius, M., & Solounias, N. (2000). Functional characterization of ungulate molars using the abrasion-attrition wear gradient: A new method for reconstructing paleodiets. American Museum Novitates, 3301, 1–36.

Franzen, J. L. (1985). Exceptional preservation of Eocene vertebrates in the lake deposit of Grube Messel (West Germany). In H. B. Whittigton & S. Conway Morris (Eds.), Extraordinary fossil biotas: Their ecological and evolutionary significance. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B, 311, 181–186.

Franzmann, A. W. (1981). Alces alces. Mammalian Species, 154, 1–7.

Frick, C. (1937). Horned ruminants of North America. American Museum of Natural History Bulletin, 59, 1–669.

Gabunia, L. (1964). The Oligocene mammalian fauna of Benara (268 pp). Academy of Sciences of URSS.

Gabunia, L. (1966). Sur les Mammifères oligocènes du Caucase. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 7, 857–869.

Gagnon, M., & Chew, A. E. (2000). Dietary preferences in extant African Bovidae. Journal of Mammalogy, 81, 490–511.

Gaudant, J. (1979). Contribution à l’étude des vertébrés oligocènes de Soulce (Canton du Jura). Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 72, 871–895.

Gentry, A. W, Rössner, G. E., & Heizmann, E. P. J. (1999). Suborder Ruminantia. In G. E. Rössner & K. Heissig (Eds.), The Miocene land mammals of Europe (pp. 225–258). München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil.

Geraads, D., Bouvrain, G., & Sudre, J. (1987). Relations phyletiques de Bachitherium Filhol, ruminant de l’Oligocène d’Europe occidentale. Palaeovertebrata, 17, 43–73.

Ghaffar, A., Khan, M. A., Akhtar, M., Qureshi, M. A., Farooq, U., & Nazir, M. (2006). The oldest Cervid from the Siwalik Hills of Pakistan. Journal of Applied Science, 6, 127–130.

Gordon, I. J., & Illius, A. W. (1988). Incisor arcade structure and diet selection in ruminants. Functional Ecology, 2, 15–22.

Greppin, J. B. (1855). Notes géologiques sur les terrains modernes, quaternaires et tertiaires du Jura bernois et en particulier du Val de Delémont. Compléments aux notes géologiques (Vol. 14, 52 pp). Neue Denkschriften der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft.

Guo, J., Dawson, M., & Beard, K. C. (2000). Zhailimeryx, a new Lophiomerycid Artiodactyl (Mammalia) from the Late Middle Eocene of Central China and early evolution of ruminants. Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 7, 239–258.

Heissig, K. (1978). Fossilführende Spaltenfüllungen Süddeutschlands und die Ökologie ihrer oligozänen Huftiere. Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie, 18, 237–288.

Heissig, K. (1987). Changes in the rodent an ungulate fauna in the Oligocene fissure fillings of Germany. Münchener Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 10, 101–108.

Heizmann, E. P. J., Duranthon, F., & Tassy, P. (1996). Miozäne Großsäugetiere. Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie C, 39, 1–60.

Hooker, J. J., Collinson, M. E., & Sille, N. P. (2004). Eocene–Oligocene mammalian faunal turnover in the Hamphire Basin, UK: Calibration to the global time scale and the major cooling event. Journal of the Geological Society, London, 161, 161–172.

Hooker, J. J., Grimes, S. T., Mattey, D. P., Collinson, M. E., & Sheldon, N. D. (2009). Refined correlation of the UK Late Eocene–Early Oligocene Solent Group and timing of its climate history. The Geological Society of America, Special Paper, 452, 179–195.

Hope, P. P. (1977). Rumen fermentation and body weight in African ruminants. In T. J. Peterle (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13 th international congress of game biologists (pp. 141–150). Washington DC: Wildlife Society.

Janis, C. M. (1986). An estimation of tooth volume and hypsodonty indices in ungulate mammals, and the correlation of these factors with dietary preferences. Mémoires du Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris (série C), 53, 367–387.

Janis, C. M. (1987). Grades and Clades in Hornless Ruminants Evolution: The reality of the Gelocidae and the systematic position of Lophiomeryx and Bachitherium. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 7, 200–216.

Jehenne, Y. (1987). Intérêt biostratigraphique des ruminants primitifs du Paléogène et du Néogène inférieur d’Europe occidentale. Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 10, 131–140.

Joeckel, R. M. (1990). A functional interpretation of the masticatory system and paleoecology of entelodonts. Paleobiology, 16, 459–482.

Kaiser, T. M., & Rössner, G. E. (2007). Dietary resource partitioning in ruminant communities of Miocene wetland and karst palaeoenvironments in Southern Germany. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 252, 424–439.

Kingswood, S. C., & Blank, D. A. (1996). Gazella subgutturosa. Mammalian Species, 518, 1–10.

Kleiber, M. (1975). The fire of life: An introduction to animal energetics. Huntington: Krieger.

Legendre, S. (1989). Les communautés de mammifères du Paléogène (Eocène supérieur et Oligocène) d’Europe occidentale: Structures, milieux et évolution. Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 16, 1–110.

Lucas, S. G., & Emry, R. J. (1999). Taxonomy and biochronological significance of Paraentelodon, a giant Entelodon (Mammalia, Artiodactyle) from the Late Oligocene of Eurasia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19, 160–168.

Luterbacher, H. P., Ali, J. R., Brinkhuis, H., Gradstein, F. M., Hooker, J. J., Monechi, S., Ogg, J. G., Powell, J. Röhl, U., Sanfilippo, A., & Schmitz, B. (2004). The Paleogene period. In F. M. Gradstein, J. G. Ogg, & A. G. Smith (Eds.), A geological time scale (pp. 384–408). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MacFadden, B. J. (2000). Cenozoic mammalian herbivores from the Americas: Reconstructing ancient diets and terrestrial communities. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 31, 33–59.

Martinez, J.-N., & Sudre, J. (1995). The astragalus of Paleogene artiodactyls: Comparative morphology, variability and prediction of body mass. Lethaia, 28, 197–209.

Martini, E. (1990). The Rhinegraben system, a connection between northern and southern seas in the European Tertiary. Veröffentlichungen aus dem Übersee-Museum Bremen, A10, 83–98.

Matthew, W. D. (1908). Osteology of Blastomeryx and phylogeny of the American Cervidae. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 23, 535–562.

Matthews, S. C. (1973). Notes on open nomenclature and on synonymy lists. Palaeontology, 16, 713–719.

Meagher, M. (1986). Bison bison. Mammalian Species, 266, 1–8.

Meijaard, E., & Sheil, D. (2007). The persistance and conservation of Borneo’s mammals in lowland rain forests managed for timber: Observations, overviews and opportunities. Ecological Research, 23, 21–34.

Métais, G., Chaimanee, Y., Jaeger, J.-J., & Ducrocq, S. (2001). New remains of primitive ruminants from Thailand: Evidence of the early evolution of the Ruminantia in Asia. Zoologica Scripta, 30, 231–248.

Métais, G., & Vislobokova, I. (2007). Basal ruminants. In D. R. Prothero, & S. C. Foss (Eds.), The evolution of artiodactyls (pp. 189–212). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Métais, G., Welcomme, J.-L., & Ducrocq, S. (2009). New lophiomericyd ruminants from the Oligocene of the Bugti Hills (Balochistan, Pakistan). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 29, 231–241.

Monteiro, L. R., & Reis, S. F. dos (1999). Pincipíos de morfometria geométrica (189p). Ribeirão Preto: Holos Editora.

Nanda, A. C., & Sahni, A. (1990). Oligocene vertebrates from the Ladakh Molasse Group, Ladakh Himalaya: Paleobiogeographic implications. Journal of Himalayan Geology, 1, 1–10.

Nanda, A. C., & Sahni, A. (1998). Ctenodactyloid rodent assemblage from Kargil Formation, Ladakh Molasse Group: Age and palaeobiogeographic implications for the Indian subcontinent in the Oligo-Miocene. Geobios, Mémoire spécial, 31, 533–544.

Perez-Barberia, F. J., & Gordon, I. J. (1999). The functional relationship between feeding type and jaw and cranial morphology in ungulates. Oecologia, 118, 157–165.

Pfirter, U. (1997). Feuille: 1106 Moutier. Atlas géologique de la Suisse 1/25’000. Notice explicative (Vol. 96, 71 pp.).

Pfirter, U., Antenen, M., Heckendorn, W., Burkhalter, R. M., Gürler, B., & Krebs, D. (1996). Feuille: 1106 Moutier. Atlas géologique de la Suisse 1/25’000. Carte (Vol. 96).

Picot, L. (2002). Le Paléogène des synclinaux du Jura et de la bordure sud-rhénane: Paléontologie (ostracodes), paléoécologie, biostratigraphie et paléogéographie (Vol. 5, 240 pp.). PhD Thesis, University of Fribourg, GeoFocus.

Picot, L., Becker, D., Cavin, L., Pirkenseer, C., Lapaire, F., Rauber, G., et al. (2008). Sédimentologie et paléontologie des paléoenvironnements côtiers rupéliens de la Molasse marine rhénane dans le Jura suisse. Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 101, 483–513.

Pirkenseer, C. (2007). Foraminifera, Ostracoda and other microfossils of the Southern Upper Rhine Graben: Palaeoecology, biostratigraphy, palaeogeography and geodynamic implications (340 pp.). Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Fribourg, Switzerland.

Prothero, D. R. (2007). Family Moschidae. In D. R. Prothero & S. E. Foss (Eds.), The evolution of Artiodactyls (pp. 221–226). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Querino, R. B., Moraes, R. C. B., & de Zucchi, R. (2002). Relative Warp Analysis to study morphological variations in the genital capsule of Trichogramma pretiosum Riley (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Neotropical Entomology, 31, 217–224.

Raia, P., Carotenuto, F., Meloro, C., Piras, P., & Pushkina, D. (2010). The shape of contention: Adaptation, history, and contingency in ungulate mandibles. Evolution, doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00944.x.

Remy, J. A., Crochet, J.-Y., Sigé, B., Sudre, J., Bonis, M. de, Vianey-Liaud, M., et al. (1987). Biochronologie des phosphorites du Quercy: mise à jour des listes fauniques et nouveaux gisements de mammifères fossiles. Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 10, 169–188.

Rivals, F., Solounias, N., & Mihlbachler, M. C. (2007). Evidence for geographic variation in the diets of Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Bison in North America, and differences from the diets of recent Bison. Quaternary Research, 68, 338–346.

Rohlf, F. J. (1993). Relative warps analysis and an example of its application to mosquito wings. In L. F. Marcus, E. Bello, & A. Garcia-Valdecasas (Eds.), Contributions to morphometrics (pp. 131–159). Madrid: Museu Nacional de Ciencias Naturales.

Rollier, L. (1910). Troisième supplément à la description géologique de la partie jurasienne de la feuille VII de la carte géologique au 1:1000 000. Matériaux pour la Carte Géolgique de la Suisse (n.s.), 25, 1–230.

Rössner, G. E. (1995). Odontische und schädelanatomische Untersuchungen an Procervulus (Cervidae, Mammalia). Münchner Geowissenchaftliche Abhandlungen, 29, 127 pp.

Rössner, G. E. (2007). Family Tragulidae. In D. R. Prothero & S. C. Foss (Eds.), The evolution of artiodactyls (pp. 213–220). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sánchez, I. M., Quiralte, V., Morales, J., & Pickford, M. (2010). A new genus of tragulid ruminant from the early Miocene of Kenya. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, doi:10.4202/app.2009.0087.

Schlosser, M. (1886). Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Stammesgeschichte der Huftiere und Versuch einer Systematik der Paar- und Unpaarhufer. Morphologisches Jahrbuch, 12, 1–136.

Schmidt-Kittler, N. (1987). European reference levels and correlation tables. Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 10, 13–19.

Schmidt-Kittler, N., Vianey-Liaud, M., Mödden, C., & Comte, B. (1997). New data for the correlation of mammal localities in the European Oligocene: Biochronological relevance of the Theridomyidae. In J.-P. Aguilar, S. Legendre, & J. Michaux (Eds.), Actes du Congrès BiochroM’97. Mémoires et Travaux de l’Ecole pratique des Hautes Etudes (Vol. 21, pp. 375–395). France: Institut de Montpellier.

Smith, W. P. (1991). Odocoileus virginiatus. Mammalian Species, 388, 1–13.

Sokolov, V. E. (1974). Saiga tatarica. Mammalian Species, 38, 1–4.

Spencer, L. M. (1995). Morphological correlates of dietary resource partitioning in the African Bovidae. Journal of Mammalogy, 76, 448–471.

Stehlin, H. G. (1910). Die Säugertiere des schweizerischen Eocaens. Sechster Teil: Catodontherium – Dacrytherium – Leptotherium – Anoplotherium – Diplobune – Xiphodon – Pseudamphimeryx – Amphimeryx – Dichodon – Haplomeryx – Tapirulus – Gelocus. Nachträge, Artiodactyla incertae sedis, Schlussbetrachtungen über die Artiodactylen, Nachträge zu den Perissodactylen. Abhandlungen der Schweizerischen Paläontologischen Gesellschaft, 36, 839–1164.

Stehlin, H. G. (1914). Übersicht über die Säugetiere der schweizerischen Molasseformation, ihre Fundorte und ihre stratigraphische Verbreitung. Verhandlungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft Basel, 21, 165–185.

Sudre, J. (1984). Cryptomeryx Schlosser, 1886, tragulidé de l’Oligocène d’Europe; relations du genre et considérations sur l’origine de ruminants. Palaeovertebrata, 14, 1–31.

Sudre, J. (1995). Le Garouillas et les sites contemporains (Oligocène, MP 25) des Phosphorites du Quercy (Lot, Tar-et-Garonne, France) et leurs faunes de Vertébrés. 12. Artiodactyles. Palaeontographica (A), 236, 205–256.

Sudre, J., & Blondel, C. (1996). Sur la présence de petits gélocidés (Artiodactyla) dans l’Oligocène inférieur du Quercy (France); considérations sur les genres Pseudogelocus SCHLOSSER 1902, Paragelocus SCHLOSSER 1902 et Iberomeryx GABUNIAS 1964. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen, 3, 169–182.

Vianey-Liaud, M., & Michaux, J. (2003). Évolution « graduelle » à l’échelle géologique chez les rongeurs fossiles du Cénozoïque européen. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2, 455–472.

Wall, W. P., & Collins, C. (1998). A comparison of feeding adaptations in two primitive ruminant, Hypertragulus and Leptomeryx, from the Oligocene deposits of Badlands National Park. National Park Service Paleontological Research, 3, 13–17.

Webb, D. S., & Taylor, B. E. (1980). The phylogeny of hornless ruminants and a description of the cranium of Archaeomeryx. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 167, 117–158.

Zanazzi, A., & Kohn, M. J. (2008). Ecology and physiology of White River mammals based on stable isotope ratios of teeth. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 257, 22–37.

Ziegler, A. P. (1956). Geologische Beschreibung des Blattes Courtelary (Berner Jura). Beiträge zur Geologischen Karte der Schweiz. Geology (N.F.), 102, 1–36.

Acknowledgments

This project was financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (project 200021-115995 and 200021-126420), the Swiss Federal Roads Authority and the Office de la culture (Canton du Jura, Switzerland). The authors are grateful to Loïc Costeur and Burkart Engesser (Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, Switzerland), André Fasel (Musée d’histoire naturelle de Fribourg, Switzerland), Isabelle Groux (Paléontologie A16 collection of the Musée jurassien des sciences naturelles, Switzerland), Suzanne Jiquel (Université des Sciences et Techniques du Languedoc, Montpellier, France), and Anne-Sophie Vernon (private collection, Ouchamps, France) for providing access to their collections. The authors are indebted to Frédéric Lapaire and Gaëtan Rauber for their help in the field and Alessandro Zanazzi, Jean-Paul Billon-Bruyat, Loïc Bocat, Florent Hiard, Soffana Madani, and Laureline Scherler for helpful discussions. Special thanks go to Tayfun Yilmaz for drawing the Soulce mandible, Bernard Migy for taking the photographs, and Richard Waite who kindly improved the English. The editor Daniel Marty, the guest associate editor Loïc Costeur, and the referee Gertrud Rössner greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editorial handling: Jean-Paul Billon-Bruyat & Daniel Marty.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mennecart, B., Becker, D. & Berger, JP. Iberomeryx minor (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from the Early Oligocene of Soulce (Canton Jura, NW Switzerland): systematics and palaeodiet. Swiss J Geosci 104 (Suppl 1), 115–132 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00015-010-0034-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00015-010-0034-0