Abstract

Objectives

This paper uses a sample of convicted offenders from Pennsylvania to estimate the effect of incarceration on post-release criminality.

Methods

To do so, we capitalize on a feature of the criminal justice system in Pennsylvania—the county-level randomization of cases to judges. We begin by identifying five counties in which there is substantial variation across judges in the uses of incarceration, but no evidence indicating that the randomization process had failed. The estimated effect of incarceration on rearrest is based on comparison of the rearrest rates of the caseloads of judges with different proclivities for the use of incarceration.

Results

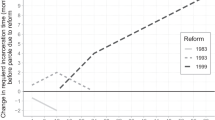

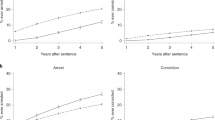

Using judge as an instrumental variable, we estimate a series of confidence intervals for the effect of incarceration on one year, two year, five year, and ten year rearrest rates.

Conclusions

On the whole, there is little evidence in our data that incarceration impacts rearrest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, sentencing guidelines routinely dictate longer prison sentences for individuals with prior convictions. Similarly, it may also be the case that prosecutors are more likely to prosecute individuals with criminal histories.

A growing literature examines how perceptions of apprehension risk are updated by the experience of apprehension or not following commission of a crime. While results vary, most such studies find that the experience of apprehension results in an upward revision in the perceived risk of apprehension and that experience of apprehension avoidance is associated with a downward revision in perceived risk. See Apel (2013) for an excellent review of the sanction perceptions literature.

Balance on observables is shown in the “Results” section.

Variation in the use of confinement is shown in the “Results” section. We also selected one county in which there was no variation in the use of confinement as a control.

Pennsylvania’s two largest counties, Allegheny and Philadelphia, assign a subset of judges to hear specific types of cases usually involving less serious charges. Our data do not identify judges who were so assigned. As a consequence, it was not possible to test for balance and differences in judge punitiveness in these two counties. For this reason they were not candidate counties for inclusion in the analysis. From the remaining 65 counties we removed 59 because there was insufficient variation in the use of confinement to merit inclusion in the analysis.

Not all sentences are reported to the Commission. (1) Philadelphia Municipal Court sentences are not reported to the Commission. These may include DUI (driving under the influence) offenses as well as other misdemeanor offenses. (2) Offenses sentenced by district magistrates are not reported to the Commission. These typically include DUI offenses or other misdemeanor offenses. (3) Murder 1 and Murder 2 offenses, which are subject to life or death mandatory sentences, do not fall under the sentencing guidelines and are not required to be reported to the Commission. The Commission encourages reporting of the Murder 1 and Murder 2 offenses; many are reported and are included in the data collection” (Pennsylvania Sentencing Commission 1999).

Prior record score is a numeric variable calculated by PASC which aims to encapsulate the seriousness of the offender’s entire prior criminal history.

For example, sentencing data indicated a period of confinement in state prison but no period of confinement could be located in the Department of Corrections files.

Our data only measure arrests that occur in Pennsylvania. We, thus, do not measure arrests that occurred outside of Pennsylvania. While we do not have data that permits us to speak to the degree to which the offenders used in this analysis were arrested outside of Pennsylvania, there is literature which measures displacement across state lines. Langan and Levin (2002) found that 7.6 % of offenders released from confinement were rearrested out of state. Similarly, Orsagh (1992) found that roughly ten percent of offenders released from eleven state prisons in 1983 would experience an out of state arrest in the 3 years following their release. Nakamura (2010) found that slightly less than 23 % of offenders arrested in New York in 1980 were not rearrested in New York, but were arrested in another state. These studies suggest that the recidivism measures used in this analysis only modestly underestimate actual re-arrest rates.

This also raises interesting questions about what exactly constitutes the treatment effect of incarceration. If one’s conceptualization of the effect of incarceration includes the aging that takes place while incarcerated, then this concern is mitigated.

This is a strong assumption, but one that can be relaxed. If their exists treatment effect heterogeneity, but judges do not sort offenders into prison based on the offender’s return from prison, then this approach estimates the mean of the treatment effect distribution. See, for example, Heckman et al. (2010).

Since the effect is, by assumption, additive, and if the proposed value is correct, the adjusted rearrest rate is the rate at which the incarcerated offender would have been rearrested if s/he had not been exposed to incarceration. Furthermore, the expected rate at which offenders would have been rearrested if not exposed to incarceration is balanced across judges due to randomization.

Recall the even though β is fixed across i, \( r_{C,i} \) varies. Thus, this relationship only holds in expectation.

To check covariate balance we use data for all 6,515 offenders sentenced in the six counties during 1999. We do so since randomization occurs at docketing and sample restrictions were made on the basis of outcomes that occur after both randomization and sentencing.

All analyses were conducted in R.

Detailed descriptive statistics, by judge, for each of the other five counties can be found in Appendix.

Where seriousness is defined as Offense Gravity Score (OGS).

Anwar and Stephens (2011), however, use a different methodological approach to estimate the dose–response function.

References

Angrist J, Imbens GW, Rubin DB (1996) Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc 91:444–472

Anwar S, Stephens M (2011) The Effect of Sentence Length on Recidivism. Working Paper. Carnegie Mellon Un.: Pgh, PA

Apel R (2013) Sanctions, perceptions and crime: implications for criminal deterrence. J Quant Crim 28

Bales WD, Piquero AJ (2012) Assessing the impact of imprisonment on recidivism. J Exp Criminol 8:71–101

Bergman GR (1976) The evaluation of an experimental program designed to reduce recidivism among second felony criminal offenders. University Microfilms Publishers, Ann Arbor

Bernburg JG, Krohn MD (2003) Labeling, life chances, and adult crime: the direct and indirect effects of official intervention in adolescence on crime in early adulthood. Criminology 41:1287–1318

Bound J, Jaeger DA, Baker RM (1995) Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instrument and the endogeneous explanatory variable is weak. J Am Stat Assoc 90:443–450

Cullen FT (2002) Rehabilitation and treatment programs. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J (eds) Crime: public policies for crime control. ICS Press, Oakland

Freeman RB (1995) Why do so many young American men commit crimes and what might we do about it? J Econ Perspect 10:25–42

Glueck S, Glueck E (1950) Unraveling juvenile delinquency. Commonwealth Fund, New York

Green DP, Winik D (2010) Using random judge assignments to estimate the effects of incarceration and probation on recidivism among drug offenders. Criminology 48:357–387

Hawkins G (1976) The prison: policy and practice. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Heckman JJ, Schmierer D, Urzua S (2010) Testing the correlated random coefficient model. J Econom 158:177–203

Imbens GW, Rosenbaum PR (2005) Robust, accurate confidence intervals with a weak instrument: quarter of birth and education. J R Stat Assoc Soc A 168:109–126

Killias M, Aebi M, Ribeaud D (2000) Does community service rehabilitate better than short-term imprisonment? Results of a controlled experiment. Howard J Crim Justice 39:40–57

Klepper S, Nagin D (1989) The Deterrent effect of perceived certainty and severity revisited. Criminology 27:721–746

Langan PA, Levin DJ (2002) Recidivism of prisoners released in 1994. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Layton MacKenzie D (2002) Reducing the criminal activities of known offenders and delinquents: crime prevention in the courts and corrections. In: Sherman LW, Farrington DP, Welsh BC, Layton MacKenzie D (eds) Evidence-based crime prevention. Routledge, London

Loeffler CE (2013) Does imprisonment alter the life-course? Evidence on crime and employment from a natural experiment. Criminology 51. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12000

Maddala GS, Jeong J (1992) On the exact small sample distribution of the instrumental variable estimator. Econometrica 60:181–183

Manski CF, Nagin DS (1998) Bounding disagreements about treatment effects: a case study of sentencing and recidivism. Soc Meth 28:99–137

Matsueda RL (1992) Reflected appraisal, parental labeling, and delinquency: specifying a symbolic interactionist theory. Am J Sociol 97:1577–1611

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1994) Personal capital and social control: the deterrence implications of individual differences in criminal offending. Criminology 32:581–606

Nagin DS, Pogarsky G (2003) An experimental investigation of deterrence: cheating, self-serving bias, and impulsivity. Criminology 41:167–193

Nagin DS, Waldfogel J (1995) The effects of criminality and conviction on the labor market status of young British offenders. Int Rev Law Econ 15:109–126

Nagin DS, Waldfogel J (1998) The effect of conviction on income through the life cycle. Int Rev Law Econ 18:25–40

Nagin DS, Cullen FT, Jonson CL (2009) Imprisonment and re-offending. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 38. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nagin DS (2013a) Deterrence: a review of the evidence by a criminologist for economists. Annual Review of Economics

Nagin DS (2013b) Deterrence in the 21st century: a review of the evidence. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 5. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nakamura K (2010) Redemption in the face of stale criminal records used in background checks. Doctoral Dissertation Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh

Nelson CR, Startz R (1990) Some further results on the exact small sample properties of the instrumental variable estimator. Econometrica 58:967–976

Nieuwbeerta P, Nagin DS, Blokland A (2009) The relationship between first imprisonment and criminal career development: a matched samples comparison. J Quant Criminol 25:227–257

Rosenbaum PR (1996) Comment on “Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables” by Angrist, Imbens, and Rubin. J Am Stat Assoc 91:465–468

Rosenbaum PR (1999) Using quantile averages in matched observational studies. Appl Stat 48:63–78

Rosenbaum PR (2002a) Observational studies, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Rosenbaum PR (2002b) Covariance adjustment in randomized experiments and observational studies (with discussion). Stat Sci 17:286–327

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1997) A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In: Thornberry TP (ed) Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

Sherman LW (1992) Policing and domestic violence. Free Press, New York

Snodgrass GM, Haviland A, Blokland A, Nieuwbeerta P, Nagin DS (2011) Does the time cause the crime? An examination of the relationship between time served and reoffending in the Netherlands. Criminology 49:1149–1194

Steffensmeier D, Ulmer JT (2005) Confessions of a dying thief. Aldine/Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

Van der Werff C (1979) Speciale Preventie. WODC, Den Haag

Waldfogel J (1994) The effect of criminal conviction on income and the trust reposed in the workmen. J Hum Res 29:62–81

Wermink H, Blokland A, Nieuwbeerta P, Nagin DS, Tollenaar N (2010) Comparing the effects of community service and short-term imprisonment on recidivism: a matched samples approach. J Exp Criminol 6:325–349

Western B (2002) The Impact of incarceration on wage mobility and inequality. Am Sociol Rev 67:526–546

Western B, Kling JR, Weiman DF (2001) The labormarket consequences of incarceration. Crime Delinq 47:410–427

Williams KR, Hawkins R (1986) Perceptual research on general deterrence: a critical overview. Law Soc Rev 20:545–572

Acknowledgments

This work was generously supported by National Science Foundation Grants SES-102459 and SES-0647576. We are also grateful to Mark Bergstrom for coordinating the data collection with the PSC, PA DOC, and the PA State Police.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors listed alphabetically. Support for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation (SES1024596). The viewpoints expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the views or beliefs of the State of Alaska.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nagin, D.S., Snodgrass, G.M. The Effect of Incarceration on Re-Offending: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Pennsylvania. J Quant Criminol 29, 601–642 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-012-9191-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-012-9191-9