Abstract

Arctic ecosystems are important carbon sinks. Increasing temperatures in these regions might stimulate soil carbon release. Evidence suggests that deciduous shrubs might counteract these carbon losses because they positively respond to increasing temperature, but their role in ecosystem carbon budgets remains uncertain. Many studies dealing with large-scale tundra greening and carbon sequestration in relation to increasing temperature have usually based their estimations on the aboveground components, but very little is known about belowground growth. In this context, annual rings can provide a retrospective insight into intra-plant temperature responses and seasonal growth allocation. This study presents a 70-year-long and annually resolved intra-plant analysis of ring width and missing ring distribution from a comprehensive serial sectioning, including 142 cross-sections and the measurements of 471 radii from ten Salix polaris Wahlenb. dwarf shrubs growing in the high Arctic on Svalbard. Results indicate a high intra-plant and inter-annual growth variation, characterized by a high proportion of partially (13.6 %) and completely (11.2 %) missing rings. The annual growth and the frequency of completely missing rings were evenly distributed inside the plant and mainly controlled by summer temperatures. Radial growth in the belowground parts appeared to be proportionally higher during long and warm summers and lower in cold early growing seasons than in the aboveground parts. The results reveal a diverging allocation between aboveground and belowground growth depending on the climatic conditions. Favorable years promoted root allocation since root radial growth occurs after aboveground growth. The observed belowground responses suggest that shrub carbon allocation might be higher than estimated only from the aboveground compartments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to predictions of various international assessments (e.g. ACIA 2004), climate change will significantly influence the polar environment with important negative consequences for the large carbon stock held in the soils (McKane et al. 1997). As arctic plants are assumed to be constrained by temperature (Billings 1987), most researchers expect recent warming to increase growth, abundance, and cover expansion toward the northern limits of arctic woody plants (Sturm et al. 2001; Tape et al. 2006; Forbes et al. 2010; Myers-Smith et al. 2011a; Natali et al. 2012), leading eventually to changes in the composition and structure of the arctic tundra (Chapin et al. 2005; Euskirchen et al. 2009; Elmendorf et al. 2012a) and increased carbon sequestration. The magnitude of new carbon sequestration by arctic shrubs compared with soil carbon losses remains uncertain. Recent studies on tundra ecosystems have shown that the patterns of plant growth response to climate change are heterogeneous and subject to regional variations (Hudson and Henry 2009; Campioli et al. 2012; Epstein et al. 2012). In particular, the growth response to experimental warming of single shrub species appears to range from positive to insignificant (Havström et al. 1993; Hudson and Henry 2010; Elmendorf et al. 2012a, b), which suggests either that other factors influence plant growth or that the response is delayed. Positive growth responses to increasing temperature have been observed in various Salix spp and for Betula nana (Jones et al. 1997; Shaver et al. 2001; Bret-Harte et al. 2002; Hill and Henry 2011; Myers-Smith et al. 2011b), as well as in graminoids and forbs (Myers-Smith et al. 2011a; Walker et al. 2012), but declines have been observed in lichens and mosses (Jägerbrand et al. 2006). A recent analysis of midsummer CO2 flux data across arctic and boreal biomes indicates that net ecosystem CO2 exchange depends on shrub cover and soil microclimate, being a sink only in woody sites with cold soils (Cahoon et al. 2012), emphasizing the importance of the belowground processes.

Many of the studies dealing with large-scale tundra greening and the carbon-cycle in the Arctic have usually based their estimations of plant responses to temperature on observations performed on the aboveground parts of the plants, i.e. with satellite observations or aboveground biomass estimation (Fraser et al. 2012; Walker et al. 2012). Aboveground growth and belowground growth are both important components of the terrestrial ecosystem carbon stock (Shaver et al. 1992). In the Arctic, the root mass fraction is in general higher than in other regions (Jackson et al. 1996; Jónsdóttir et al. 1996; Mokany et al. 2006). Thus, neglecting the belowground responses to warming might lead to a biased estimation and to an incomplete understanding of climate-induced changes in vegetation.

The intra-plant and inter-annual growth patterns of tundra shrubs can help to improve the understanding of growth allocation responses and their influence on ongoing changes in the arctic ecosystem. A comparison of the allocation of the above- and belowground biomass in terms of annual growth provides ecological insights into the responses of whole plants to environmental changes (Monk 1966; Smith and Klinger 1985; Poorter et al. 2012) and allows a better estimation of future carbon allocation in relation to changing environmental conditions. Most studies on arctic shrub species have focused on variables such as phenology, reproductive effort, or canopy cover, which can be measured with minimal disturbance and non-destructive methods (Hollister et al. 2005). They do not, however, allow a retrospective analysis of changes over the years.

Tree-ring studies of relatively long-living arctic shrubs (30–100 years old) growing in the high Arctic have the potential to supply more insights into how shrubs’ allocation of growth is affected by a changing climate. Arctic shrubs are known to have intra-plant growth irregularities, such as the complete or partial absence of growth during years with limiting conditions for cambium activity. The absence of growth is usually associated with a missing ring, which reflects “a gap” in the sequence of a tree-ring series. Polunin (1955) observed that some Salix arctica individuals in the Canadian Arctic showed little or no growth in specific years. This was confirmed later by Beschel and Webb (1963) who found that many years may pass without any rings being formed in S. arctica specimens found on Axel Heiberg Island. This phenomenon is usually linked with “low extremes”, represented by one or more cold summers with little or no growth (e.g. Polunin 1955, 1958). However, such growth irregularities might not be continuous along the whole axis of a stem (Hallinger et al. 2010; Novak et al. 2011), and thus, their distribution within the plant could represent a valuable indicator of how plants allocate growth under limiting conditions such as those prevailing in the high Arctic.

The aim of this study was (1) to quantify intra-plant growth patterns of arctic shrubs based on the example of a deciduous shrub Salix polaris Wahlenb. growing in a high Arctic site at the cold limit of its distribution area and (2) to relate observed intra-plant and intra-annual growth to seasonal climatic variations (3) to better understand whole plant growth responses. Salix polaris is a prostrate dwarf shrub widely distributed across the Arctic, known as a later colonizer of deglaciated areas (Nakatsubo et al. 2010; Fujiyoshi et al. 2011). Usually, it grows less than 10 cm in height and takes the form of mats. According to a recent study, this species plays a significant role in carbon sequestration due to its high leaf photosynthetic capacity (Muraoka et al. 2008). Specifically, we investigated the annual radial increments and the proportion of partially and completely missing rings in the aboveground and belowground parts of the shrubs to determine whether and how intra-plant growth allocation varied with changing temperature.

Materials and methods

Study area

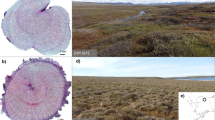

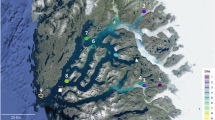

The study area is situated close to Petunia Bay, northern Billefjorden (78°43′N; 16°37′E), in the central part of Spitsbergen (Svalbard Archipelago, Norway) (Fig. 1a). The bedrock is complex and consists of metamorphic outcrops and sedimentary formations (Dallmann 2004). Soils are influenced by permafrost with an active layers reaching up to 1.2 m thickness (Rachlewicz and Szczucinski 2008).

Study area characteristics: (a) location of the study area in central Spitsbergen (Petuniabukta) and meteorological station in Longyearbyen; (b) ombrothermic diagram (mean for the period August 1975–December 2010) for the closest meteorological station located in Longyearbyen–Svalbard Airport weather station; data provided by Norwegian Meteorological Institute (DNMI 2011); (c) overview of the study area with locations of sampling plots in Ebba valley and Hørbye glacier forefield

The study site is located in the middle arctic tundra zone (Elvebakk 1999; Walker et al. 2005), characterized by cold, dry, and windy conditions. In Longyearbyen, 70 km south of the study site, the mean annual temperature is −5.3 °C, with annual precipitation of 184 mm (Fig. 1b, based on Norwegian Meteorological Institute data from Svalbard Airport weather station, period August 1975–2010, DNMI 2011). Data collected for the years 2001–2010 indicated that, in comparison with Longyearbyen, the study area experiences a more continental climate, with 1–2 °C more during summer and with precipitation from June to September not exceeding 60 mm (Rachlewicz and Styszyńska 2007). Snow cover is irregular depending on vegetation cover, local topography, and wind activity. The snow-free period usually spans from mid-June to mid-September. The vegetation lies within the high Arctic Dryas octopetala tundra type (Rønning 1996), with dominance of the deciduous polar willow (S. polaris Wahlenb.). The vegetation cover is discontinuous, and within the sampling plot, it does not exceeds 30 %. The growing season is very short, usually extending from June to August, with average temperatures ranging from 3.3 °C (1982) to 6.4 °C (2007) (DNMI 2011).

Shrub sampling and dendrochronological survey

Intact S. polaris shrubs complete with aboveground and belowground plant parts were collected at the bottom of the Ebba valley and within the Hørbye glacier forefield (Fig. 1c) at the end of August 2010. The sampling only considered isolated, mature, and healthy individuals to avoid competition-influenced plant structures. For each sampled individual, the precise location and the mat size were documented.

The dendrochronological survey followed the serial sectioning approach proposed by Kolishchuk (1990), which consists of repeated tree-ring width measurements and cross-dating at the intra-plant level. Serial sectioning was performed on a sub-selection of ten shrubs for a total of 142 cross-sections and on 471 radii (Table 1). Only plants free from visible external injuries that were relatively old and with a root collar ring structure without major irregularities (eccentricity, damage, or decay) were considered. The numerous sections and radii did not allow for a large sample of individual plants. The sub-selection included nine shrubs from the bottom of the Ebba valley, which were growing on a raised marine terrace within a radius of 20 m and one additional individual (H21, Table 1) from the Hørbye glacier forefield due to its wide rings.

The plant sectioning was performed for both belowground and aboveground segments (Fig. 2). Cross-sections were collected along the main growth axis, starting from the root collar down along the main root, including taproots, if available, and up along the stem, if any, and along a maximum of four main branches. The distance of each cross-section from the root collar was measured. To reduce dating errors, asymmetric, twisted, and bent parts of the plant were excluded from sectioning. The number of sections per plant (from 7 to 22) was defined according to the plant morphology. Sectioning was preferentially performed on the main root since it provides the oldest records. Each part of the plant was labeled and preserved in case supplementary sectioning became necessary.

Example of a serial sectioning as performed on the shrub K07: (a) the position of the sections selected for tree-ring analyses along the sections of the root (indicated with the letter A) and the branches (B and C); (b) an example of a thin section used for tree-ring measurement, with a magnified inlet presenting common partially missing rings (PMR); (c) the summary of cross-dated ring-width (RW) measurements of a single S. polaris Wahlenb. shrub together with the detections of PMR (filled circles) and missing rings (MR, open circles) along each cross-section positioned according to their distance from the root collar. Lines for aboveground growth series indicate the two main branches sectioned

Thin sections of the whole cross-section (approx. 15–20 μm thick) were obtained with a sledge microtome (WSL-Lab-microtome), stained with a mixture of Safranin and Astra blue, and permanently fixed on microslides with Canada balsam (Schweingruber and Poschlod 2005; Schweingruber et al. 2011). Images were captured using a digital camera (ColorView III, Olympus) connected to a microscope (Olympus BX41) under ×40–×100 magnification. Partial images of a single cross-section were digitally stitched together using the Photomerge function in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Incorporated, USA). Special attention was given to ensure that no distortion or scale change occurred when creating the combined images. Depending on growth eccentricity and frequency of partially rings, we measured two to six radii per section. Ring widths (RW) were measured using the software WinCell (Regent Instruments, Canada). The identification of annual rings was carefully determined by considering the entire cross-section and not only along the single radii, to account for the numerous partially and missing rings.

Cross-dating and chronology development

Due to the relatively short time-series (<50 years) characterized by the presence of numerous missing and partially MR (see Fig. 2c), cross-dating has been primarily performed on visual criteria. This fundamental and delicate process has been achieved with a bottom-up approach, first by visually cross-dating the radii of each section and then the sections of each plant and finally between the plants. Where incongruities were found, the verification followed a back and forward process to identify and correct the errors. The comparison of growth patterns was based on the presence of pointer years (Schweingruber et al. 1990), generally represented by well-developed wide rings, which could be easily distinguished in most of the sections. Ring-width matching was complemented by the method applied to tropical species (Wils et al. 2009, 2011), which uses other visual features, such as vessel size and density. A ring was defined to be partially missing rings (PMR) if missing from at least one radius of a particular cross-section, but still observed along other radii of the same section. Analogously, a ring was defined to be missing (MR) if absent in the aboveground or/and in the belowground cross-sections (see Fig. 2c for an example), but still present in the other plants. Missing rings were inserted into the time-series with the value of zero. Finally, to account for the numerous limitations resulting from the large number of introduced missing rings, the cross-dating quality was checked using the COFECHA software (Holmes 1983; Grissino-Mayer 2001).

After cross-dating, ring-width chronologies (RW) for the belowground and aboveground parts were developed. These chronologies were built by first averaging all radii belonging to the same section and then all section averages of the same plant and finally the 10 plant averages. The belowground chronology included all root and taproot sections, while the aboveground chronology contained all branch and stem sections. Similarly, we calculated the chronology for the whole plant (plant average) and for the root collar sections (root collar). Finally, a difference chronology between belowground and aboveground growth (RW difference) was obtained by averaging the difference between the belowground and aboveground chronologies calculated for each individual. Since there were no evident age-related trends in the time-series, no detrending procedures were applied. The strength of the common signal of the chronologies was quantified using the mean correlation between the time-series (Rbt) (Briffa and Jones 1990) and the expressed population signal (EPS) (Wigley et al. 1984).

Climate–growth relationships

Climate–growth relationships were established by computing both Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlations between chronologies and monthly climatic data (from previous April to current September). This period has been chosen in order to cover the months likely affecting growth, including the current and the previous growing season and the winter in between. Correlations were performed for the period 1975–2010, when at least 50 % of the samples were represented in the chronology and the inter-series correlation (Rbt) was above 0.5. Homogenized monthly mean temperature and precipitation sums were obtained from the Svalbard Airport weather station (1975–2010; 78°25′N, 15°47′E; 28 m a.s.l.; DNMI 2011).

Results

Tree-ring width chronologies

We obtained a 70-year-long and annually resolved aboveground and belowground RW chronologies. The oldest time-series in the chronology goes back to 1941, but a sample depth with at least four plants starts in 1963. The mean plant age was 48 years (Table 2), with the oldest plant parts always found belowground and usually in close proximity to the root collar. The annual growth rate was extremely low, with an average ring width of 55 μm. A maximum value of 480 μm was measured for the year 1993 in the individual H21 growing in the glacier forefield. The average growth rate was higher for the belowground (60 μm) than aboveground (48 μm) plant parts. The common signal (Rbt) was 0.27, 0.40, 0.37, and 0.38 for root collar, plant average, above- and belowground chronologies, respectively. Given the sample size of 10 plants, this corresponds to the EPS of, respectively, 0.79, 0.87, 0.85, and 0.86. The Plant average chronology was characterized by high mean sensitivity (MS = 0.45).

From a total of 5299 rings, we identified 24.8 % as missing rings, which corresponds to 11.2 % as completely MR and 13.6 % as partially missing rings (PMR) (Table 2). This rate corresponds to an average of 9.2 MR of both types per analyzed section. The distribution and the frequency of MR were observed to be unrelated to shrub age or the size of the stem. The rate of completely MR was higher in the belowground (12.5 %) than in the aboveground (8.8 %) plant parts. In contrast, the number of partially MR was higher in the aboveground than in belowground parts (i.e. 16.0 % versus 12.1 %). For the entire plant, annual growth irregularities, including both PMR and MR, reached on average 24.1 % (min = 9.8 %; max = 40.5 %). The mean rate of PMR per plant was 13.4 % (min = 4.3 %; max = 21.3 %), whereas the mean MR rate was 10.7 % (min = 2.3 %; max = 22.1 %).

The variability in both the average growth rate and the percentage of MR within the plants and over time was high (Figs. 3, 4). Nevertheless, there were some recognizable patterns. The annual ring widths were generally larger belowground than aboveground, especially for the main root at a depth between 0 and 10 cm. The frequency of PMR appeared to be slightly lower at a depth between 5 and 15 cm (Fig. 3). When accounting for the variability between years, we observed a significant growth increase over time (e.g. the slope a = 1.19 μm × Year−1, P < 0.01) for the root collar chronology (Fig. 4a). This increase was larger for the belowground plant parts than for the aboveground parts. Depending on the chronology, the RW ranged from an average of about 20 μm during the 1970s to about 50 μm in the last decade. The PMR were evenly distributed over the years. However, in the last two decades, a slight increase in PMR associated with a decrease in the MR was observed. The MR clearly appeared in relation to specific years, with this relationship especially apparent for the annual rings in 1981, 1982, 1983, 1987, 1994, and 1999 (Fig. 4b, c).

Average ring width (a) and percentage of partially (b) and completely (c) missing rings per analyzed cross-section (n = 142) along the distance from the root collar. Solid lines indicate the average over a 5-year moving window. (d) Summarizes the proportion of missing rings (MR) and the partially missing rings (PMR), and (e) the number of sections considered in the 5-year moving window

Climate–growth relationships

The results of the climate–growth relationships showed that the average annual shrub growth rate and the percentage of MR are primarily controlled by the June–July–August (JJA) air temperatures, but not for the PMR (Figs. 5, 6, due to the similarities of results, only Pearson’s correlation is shown). The correlation between the root collar chronology and the average JJA temperatures was significant with r = 0.70 (P < 0.01).

Climate–growth relationships between (a) the root collar ring-width chronology and temperature (black bars) and precipitation (gray bars); and the proportion of partially missing rings (PMR) and missing rings (MR) for the (b) aboveground and (c) belowground chronologies. Pearson’s correlations were calculated with monthly temperature and precipitation data from Longyearbyen (Svalbard Airport meteorological station) over the period from August to December 2010 (DNMI 2011). Monthly data include previous year April (a) to current year September (S) and the current year June–July–August (JJA). Horizontal dotted lines indicate the significance levels for P < 0.05 and P < 0.01

Relationships between (a) ring width (RW), (b) missing rings (MR), and (c) partially missing rings (PMR) for belowground chronologies and mean June–July–August average temperatures (JJA) obtained from Svalbard Airport (Longyearbyen) meteorological station over the period from August 1975 to December 2010 (DNMI 2011). Linear regression indicated by lines

The correlations between the precipitation and annual growth rates revealed significant negative relationships with JJA (r = −0.39, P < 0.01) and with June precipitation (r = −0.32; P < 0.05). In addition, although the physiological understanding is not clear and the significance can be given by chance, there was a positive relationship between the root collar chronology and the previous year November precipitation (r = 0.45; P < 0.01).

The frequency of MR was negatively correlated with JJA temperatures (r = −0.45 and r = −0.53 for aboveground and belowground chronologies, respectively; P < 0.01). Comparatively, the frequency of PMR appeared to be positively influenced by May temperatures, for both aboveground (r = 0.36; P < 0.05, Rbt = 0.37) and belowground (r = 0.31; P < 0.05, Rbt = 0.38) chronologies. The PMR values also correlated with previous year temperatures, but correlated differently for aboveground chronologies (with May, June, and July, respectively: r = 0.34; r = 0.34; r = 0.30; P < 0.05) and belowground chronologies (strongest with August and October; both at 0.41; P < 0.01).

Climate growth relationships did not substantially differ between the aboveground and belowground plant parts (Fig. 5). However, when focusing on the growth differences between the aboveground and belowground parts, we observed divergent responses to temperature (Fig. 7). The RW difference chronology i.e. the chronology obtained from the difference between the average belowground and aboveground of each plant (Rbt = 0.09) was positively correlated with both JJA (r = 0.41, P < 0.01) and negatively with March–April–May (MAM) temperatures (r = −0.34, P < 0.05).

(a) Time-series (gray lines) and average chronology (bold black line) of differential growth (RW difference) between belowground and aboveground plant parts over the years from 1975 to 2010 (n = 10). (b) Climate growth relationships between the average of the ring-width difference and the monthly temperature data from Svalbard Airport (Longyearbyen) meteorological station over the period from August 1975 to December 2010 (DNMI 2011). Monthly data include July of the previous year (j) to September of the current year (S) and the composites for June–July–August (JJA) and March–April–May (MAM). Horizontal dotted lines indicate the significance levels for P < 0.05 and P < 0.01

Discussion

Allocation priorities

Our results suggest that growth is not homogenously allocated within the different plant segments and that the diverging allocation occurs in relation to temperature. Despite the high intra-plant growth variability, relevant trends of allocation priorities between plant segments have been identified. Cambial age and ring width were at their maximum close to the root collar (up to 7 cm below it) and decreased only slightly toward the apex. The age of lower roots parts (approx. 30 cm distance from the root collar) was up to 15 years older than in the aboveground shoots (Fig. 2c), and the average growth rate was 20 % higher in roots (60 μm) than in shoots (48 μm). These differences suggest a preferential allocation of resources to the less damage exposed and longer-living roots, as observed for other prostrate willow species growing in the high Arctic (Beschel and Webb 1963). In addition, these results confirm that the root-to-shoot ratio is higher in arctic tundra vegetation than in ecosystems with less harsh environmental conditions (e.g. Billings and Mooney 1968; Bliss 1971; Chapin 1977; Webber 1977; Jackson et al. 1996). These findings highlight the important role of roots for plant survival even after partial dieback of the aboveground parts and evidence of their significance in the process of long-term carbon storage.

Inter-annual growth variability and temperature

The secondary growth of arctic shrubs is limited by the high Arctic environmental conditions (Billings 1987). Our results show that mean radial growth rate of S. polaris of 79 μm per year (as observed at the root collar and excluding missing rings) is most likely one of the lowest annual radial growth rates ever described for tundra woody plants (Polunin 1958; Woodcock and Bradley 1994). In our chronologies, growth varied greatly from year to year. This variability was primarily associated with growing season temperatures (Fig. 5), as observed for several other arctic tundra sites and species (e.g. Wilson 1957; Havström et al. 1995; Bär et al. 2006; Rayback and Henry 2006; Rozema et al. 2009; Forbes et al. 2010; Hallinger et al. 2010; Weijers et al. 2010; Blok et al. 2011; Weijers et al. 2012). The negative response to summer (June to August) precipitation (Fig. 5a) indicates that precipitation only indirectly affects shrub growth by reducing solar radiation and temperature and also reveals that the selected shrubs, despite growing on a relatively dry site, are not exposed to drought. The dependence on temperature was also observed when considering the low-frequency trends. The increasing growth rate and the decreasing number of MR observed within the last decade (Fig. 4) suggest that Svalbard, like many other arctic regions, is also experiencing an increasing shrub productivity in response to climate warming (Sturm et al. 2001; Tape et al. 2006; Callaghan et al. 2011; Naito and Cairns 2011; Myers-Smith et al. 2011b; Walker et al. 2012).

In our study, growth anomalies were represented by 24.8 % of all the rings considered (Table 2). Nevertheless, the shrubs investigated in this study demonstrated an ability to survive for several decades (48 years on average and up to a maximum of 70 years). Missing rings were found to be mainly coupled to cold growing seasons (Fig. 5). These results confirm the commonly reported “missing rings phenomenon” observed for other arctic and alpine tundra species (Polunin 1955, 1958; Beschel and Webb 1963; Woodcock and Bradley 1994; Bär et al. 2006; Schmidt et al. 2006; Hallinger et al. 2010). According to Chapin (1983), low temperatures limit in several ways the rate at which resources like carbon and nutrients become available to arctic plants, and therefore, they may not directly limit shrub growth themselves. Recently, Wilmking et al. (2012) linked the absence of annual rings in the lower part of the stem in arctic and alpine tundra species with a group of factors, such as slow stem downwards auxin transport, low temperatures and short growing season length, lack of nutrients and available water, cambial age, and plant growth form. Our results, however, confirm that the absence of growth (MR) during cold growing seasons is very likely related to the incapacity of the cambium to divide, rather than to the inability to perform photosynthesis (Körner 2006). Nevertheless, the existence of growth rings formed in the years 1983, 1987, and 1994, which average JJA temperatures were about 4 °C, indicates that xylogenesis in shrubs can occur at lower temperatures than 6–8 °C reported for trees growing at the tree line (Körner and Paulsen 2004; Rossi et al. 2007; Deslauriers et al. 2008). In contrast to the MR, the absence of clear correlations between frequency of PMR and temperature (Figs. 5, 6), as well as the absence of PMR pattern along roots and branches (Fig. 3) and the higher frequency of PMR observed for the aboveground parts (Table 2), leads us to conclude that other determinants might have superimposed the temperature signal, as for example a limited growth capacity (Lorimer et al. 1999) in response to mechanical or biological disturbances (i.e. herbivores). Finally, other factors such as late snowmelt or ice encasements might delay the onset of the growing season or reduce summer growth leading to PMR or MR (Wipf 2010; Cooper et al. 2011; Preece and Phoenix 2013), and thus, an unequivocal physiological explanation for their formation in arctic shrubs remains unresolved.

Temperature modulates root-to-shoot growth allocation

The correlation between climate data and the growth differential between aboveground and belowground plant parts shows that temperature modulates intra-plant growth (Fig. 7). Although with a weak common signal due to the high growth irregularities, results suggest that a warm summer (JJA) promotes larger growth differences between roots and branches, favouring more resource allocation to the belowground parts of the shrub. The opposite occurs, but in a more diffused way (P < 0.05), during cold springs (MAM). Our interpretation is that resource allocation within the shrub appears to be dependent on the seasons and their temperatures due to a phenological shift in growth between the aboveground and belowground plant segments. Early in the growing season, shoot growth is favored to ensure that crown and leaves develop, while belowground growth occurs later in the season. This hypothesis is supported by Kummerow et al. (1983), who observed that aboveground shoots of Betula glandulosa and Salix pulchra in Alaska developed at least 1 week before the fine roots, which reached a maximum in biomass later in the growing season. A similar shift has been observed by monitoring secondary growth formation in the Canadian boreal forest, where cell production in the stem appeared to be concentrated early in the season (June) and the highest rates of cell division in roots occurred 1 month later (Thibeault-Martel et al. 2008). Consequently, we could expect that a cold spring delays the onset of the growing season, resulting in not enough time to fully allocate resources for growth in the belowground parts. Conversely, a warm growing season will promote additional carbon assimilation with the part not invested in the shoots allocated in the roots. This would explain the results summarized in Fig. 7, which suggest that the length of the growing season, determined by temperature, is the main factor limiting growth in roots.

Conclusion

The comprehensive serial sectioning performed in this study provided a unique annually resolved retrospective of 70 years of S. polaris growth allocation. Although based on only ten plants growing at one specific site, our findings suggest that S. polaris prioritize growth in the more protected and long-living belowground segments. Summer temperature was found to be the main determinant for annual growth. However, since roots growth is phenologically postponed after shoot growth, their growth can be prioritized only in years with long and warm growing seasons. The observed belowground responses suggest that shrubs’ carbon allocation in a warming climate might thus be higher than estimated only from the aboveground plant parts.

References

ACIA (2004) Arctic climate impact assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, Impact of a Warming Arctic

Bär A, Bräuning A, Löffler J (2006) Dendroecology of dwarf shrubs in the high mountains of Norway? A methodological approach. Dendrochronologia 24:17–27

Beschel R, Webb D (1963) Growth ring studies on Arctic willows. Axel Heiberg Island: preliminary report. Montreal

Billings WD (1987) Constraints to plant-growth, reproduction, and establishment in arctic environments. Arct Alp Res 19:357–365. doi:10.2307/1551400

Billings WD, Mooney HA (1968) The ecology of arctic and alpine plants. Biol Rev 43:481–529

Bliss LC (1971) Arctic and alpine plant life cycles. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S 2:405–438

Blok D, Sass-Klaassen U, Schaepman-Strub G, Heijmans MMPD, Sauren P, Berendse F (2011) What are the main climate drivers for shrub growth in Northeastern Siberian tundra? Biogeosciences 8:1169–1179. doi:10.5194/bg-8-1169-2011

Bret-Harte MS, Shaver GR, Chapin FS (2002) Primary and secondary stem growth in arctic shrubs: implications for community response to environmental change. J Ecol 90:251–267. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2001.00657.x

Briffa K, Jones P (1990) Basic dendrochronology statistics and assessment. In: Cook E, Kairiukstis L (eds) Methods in dendrochronology: applications in the environmental sciences. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 137–153

Cahoon SMP, Sullivan PF, Shaver GR, Welker JM, Post E (2012) Interactions among shrub cover and the soil microclimate may determine future Arctic carbon budgets. Ecol Lett 15:1415–1422. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01865.x

Callaghan TV, Christensen TR, Jantze EJ (2011) Plant and vegetation dynamics on Disko Island, West Greenland: snapshots separated by over 40 years. Ambio 40:624–637. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0169-x

Campioli M, Leblans N, Michelsen A (2012) Stem secondary growth of tundra shrubs: impact of environmental factors and relationships with apical growth. Arct Antarct Alp Res 44(1):16–25. doi:10.1657/1938-4246-44.1.16

Chapin FS (1977) Temperature compensation in phosphate absorption occurring over diverse time scales. Arct Alp Res 9:139–148

Chapin FS (1983) Direct and indirect effects of temperature on arctic plants. Polar Biol 2:47–52

Chapin FS, Sturm M, Serreze MC, McFadden JP, Key JR, Lloyd AH, McGuire AD, Rupp TS, Lynch AH, Schimel JP, Beringer J, Chapman WL, Epstein HE, Euskirchen ES, Hinzman LD, Jia G, Ping CL, Tape KD, Thompson CDC, Walker DA, Welker JM (2005) Role of land-surface changes in Arctic summer warming. Science 310:657–660. doi:10.1126/science.1117368

Cooper EJ, Dullinger S, Semenchuk P (2011) Late snowmelt delays plant development and results in lower reproductive success in the High Arctic. Plant Sci 180:157–167. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.09.005

Dallmann WK (2004) Increasing interest for the conservation of geological sites in the West European Arctic. ProGeo News 2:1–4

Deslauriers A, Rossi S, Anfodillo T, Saracino A (2008) Cambial phenology, wood formation and temperature thresholds in two contrasting years at high altitude in southern Italy. Tree Physiol 28:863–871

DNMI (2011) eKlima, free access to weather- and climate data from Norwegian Meteorological Institute from historical data to real time observation. http://eklima.met.no. Accessed 11 Nove 2011

Elmendorf SC, Henry GHR, Hollister RD, Björk RG, Bjorkman AD, Callaghan TV, Collier LS, Cooper EJ, Cornelissen JHC, Day TA, Fosaa AM, Gould WA, Grétarsdóttir J, Harte J, Hermanutz L, Hik DS, Hofgaard A, Jarrad F, Jónsdóttir IS, Keuper F, Klanderud K, Klein JA, Koh S, Kudo G, Lang SI, Loewen V, May JL, Mercado J, Michelsen A, Molau U, Myers-Smith IH, Oberbauer SF, Pieper S, Post E, Rixen C, Robinson CH, Schmidt NM, Shaver GR, Stenström A, Tolvanen A, Totland O, Troxler T, Wahren CH, Webber PJ, Welker JM, Wookey PA (2012a) Global assessment of experimental climate warming on tundra vegetation: heterogeneity over space and time. Ecol Lett 15:164–175. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01716.x

Elmendorf SC, Henry GHR, Hollister RD, Björk RG, Boulanger-Lapointe N, Cooper EJ, Cornelissen JHC, Day TA, Dorrepaal E, Elumeeva TG, Gill M, Gould WA, Harte J, Hik DS, Hofgaard A, Johnson DR, Johnstone JF, Jónsdóttir IS, Jorgenson JC, Klanderud K, Klein JA, Koh S, Kudo G, Lara M, Levesque E, Magnusson B, May JL, Mercado-Diaz JA, Michelsen A, Molau U, Myers-Smith IH, Oberbauer SF, Onipchenko VG, Rixen C, Schmidt NM, Shaver GR, Spasojevic MJ, Porhallsdottir PE, Tolvanen A, Troxler T, Tweedie CE, Villareal S, Wahren CH, Walker X, Webber PJ, Welker JM, Wipf S (2012b) Plot-scale evidence of tundra vegetation change and links to recent summer warming. Nat Clim Ch 2:453–457. doi:10.1038/Nclimate1465

Elvebakk A (1999) Bioclimatic delimitation and subdivision of the Arctic. In: Nordal I, Razzhivin Y (eds) The species concept in the high north: a panarctic Flora initiative. The Norwegian Academy of Science and letters, Oslo

Epstein HE, Raynolds MK, Walker DA, Bhatt US, Tucker CJ, Pinzon JE (2012) Dynamics of aboveground phytomass of the circumpolar Arctic tundra during the past three decades. Environ Res Lett 7(1). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/1/015506

Euskirchen ES, McGuire AD, Chapin FS, Yi S, Thompson CC (2009) Changes in vegetation in northern Alaska under scenarios of climate change, 2003–2100: implications for climate feedbacks. Ecol Appl 19:1022–1043. doi:10.1890/08-0806.1

Forbes BC, Fauria MM, Zetterberg P (2010) Russian Arctic warming and ‘greening’ are closely tracked by tundra shrub willows. Glob Chang Biol 16:1542–1554. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02047.x

Fraser R, Olthof I, Carriere M, Deschamps A, Pouliot D (2012) A method for trend-based change analysis in Arctic tundra using the 25-year Landsat archive. Polar Rec 48:83–93. doi:10.1017/S0032247411000477

Fujiyoshi M, Yoshitake S, Watanabe K, Murota K, Tsuchiya Y, Uchida M, Nakatsubo T (2011) Successional changes in ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with the polar willow Salix polaris in a deglaciated area in the High Arctic, Svalbard. Polar Biol 34:667–673. doi:10.1007/s00300-010-0922-9

Grissino-Mayer HD (2001) Evaluating crossdating accuracy: a manual and tutorial for the computer program COFECHA. Tree-Ring Res 57:205–221

Hallinger M, Manthey M, Wilmking M (2010) Establishing a missing link: warm summers and winter snow cover promote shrub expansion into alpine tundra in Scandinavia. New Phytol 186:890–899. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03223.x

Havström M, Callaghan TV, Jonasson S (1993) Differential growth-responses of Cassiope-Tetragona, an Arctic Dwarf-Shrub, to environmental perturbations among 3 contrasting high sites and sub-arctic sites. Oikos 66:389–402. doi:10.2307/3544933

Havström M, Callaghan TV, Jonasson S, Svoboda J (1995) Little ice-age temperature estimated by growth and flowering differences between subfossil and extant shoots of Cassiope tetragona, an arctic heather. Funct Ecol 9:650–654

Hill GB, Henry GHR (2011) Responses of high Arctic wet sedge tundra to climate warming since 1980. Glob Change Biol 17:276–287. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02244.x

Hollister RD, Webber PJ, Bay C (2005) Plant response to temperature in Northern Alaska: implications for predicting vegetation change. Ecology 86:1562–1570. doi:10.1890/04-0520

Holmes R (1983) Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement. Tree-Ring Bull 43:69–78

Hudson JMG, Henry GHR (2009) Increased plant biomass in a High Arctic heath community from 1981 to 2008. Ecology 90:2657–2663. doi:10.1890/09-0102.1

Hudson JMG, Henry GHR (2010) High Arctic plant community resists 15 years of experimental warming. J Ecol 98:1035–1041. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01690.x

Jackson RB, Canadell J, Ehleringer JR, Mooney HA, Sala OE, Schulze ED (1996) A global analysis of root distributions for terrestrial biomes. Oecologia 108:389–411. doi:10.1007/Bf00333714

Jägerbrand AK, Lindblad KEM, Bjork RG, Alatalo JM, Molau U (2006) Bryophyte and lichen diversity under simulated environmental change compared with observed variation in unmanipulated alpine tundra. Biodivers Conserv 15:4453–4475. doi:10.1007/s10531-005-5098-1

Jones MH, Bay C, Nordenhäll U (1997) Effects of experimental warming on arctic willows (Salix spp.): a comparison of responses from the Canadian High Arctic, Alaskan Arctic, and Swedish Subarctic. Glob Change Biol 3:55–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.1997.gcb135.x

Jónsdóttir IS, Callaghan TV, Headley AD (1996) Resource dynamics within arctic clonal plants. Ecol Bull 45:53–64. doi:10.2307/20113183

Kolishchuk V (1990) Dendroclimatological study of prostrate woody plant. In: Cook ER, Kairiukstis LA (eds) Methods of dendrochronology applications in the environmental sciences. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht [etc.], p 394

Körner C (2006) Significance of temperature in plant life. In: Morison JIL (ed) Plant growth and climate change. Vol biological sciences series. Blackwell, Oxford, p 213

Körner C, Paulsen J (2004) A world-wide study of high altitude treeline temperatures. J Biogeogr 31:713–732

Kummerow J, Ellis BA, Kummerow S, Chapin FS (1983) Spring growth of shoots and roots in shrubs of an Alaskan Muskeg. Am J Bot 70:1509–1515

Lorimer CG, Dahir SE, Singer MT (1999) Frequency of partial and missing rings in Acer saccharum in relation to canopy position and growth rate. Plant Ecol 143:189–202

McKane RB, Rastetter EB, Shaver GR, Nadelhoffer KJ, Giblin AE, Laundre JA, Chapin FS (1997) Reconstruction and analysis of historical changes in carbon storage in arctic tundra. Ecology 78:1188–1198. doi:10.1890/0012-9658

Mokany K, Raison RJ, Prokushkin AS (2006) Critical analysis of root: shoot ratios in terrestrial biomes. Glob Change Biol 12:84–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001043.x

Monk C (1966) Ecological importance of root/shoot ratios. B Torrey Bot Club 93:402–406. doi:10.2307/2483412

Muraoka H, Noda H, Uchida M, Ohtsuka T, Koizumi H, Nakatsubo T (2008) Photosynthetic characteristics and biomass distribution of the dominant vascular plant species in a high Arctic tundra ecosystem, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard: implications for their role in ecosystem carbon gain. J Plant Res 121:137–145. doi:10.1007/s10265-007-0134-8

Myers-Smith IH, Forbes BC, Wilmking M, Hallinger M, Lantz T, Blok D, Tape KD, Macias-Fauria M, Sass-Klaassen U, Levesque E, Boudreau S, Ropars P, Hermanutz L, Trant A, Collier LS, Weijers S, Rozema J, Rayback SA, Schmidt NM, Schaepman-Strub G, Wipf S, Rixen C, Menard CB, Venn S, Goetz S, Andreu-Hayles L, Elmendorf S, Ravolainen V, Welker J, Grogan P, Epstein HE, Hik DS (2011a) Shrub expansion in tundra ecosystems: dynamics, impacts and research priorities. Environ Res Lett 6(4). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/045509

Myers-Smith IH, Hik DS, Kennedy C, Cooley D, Johnstone JF, Kenney AJ, Krebs CJ (2011b) Expansion of canopy-forming willows over the twentieth century on Herschel Island, Yukon Territory, Canada. Ambio 40:610–623. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0168-y

Naito AT, Cairns DM (2011) Patterns and processes of global shrub expansion. Prog Phys Geog 35:423–442. doi:10.1177/0309133311403538

Nakatsubo T, Fujiyoshi M, Yoshitake S, Koizumi H, Uchida M (2010) Colonization of the polar willow Salix polaris on the early stage of succession after glacier retreat in the High Arctic, Ny-Alesund, Svalbard. Polar Res 29:385–390. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2010.00170.x

Natali SM, Schuur EAG, Rubin RL (2012) Increased plant productivity in Alaskan tundra as a result of experimental warming of soil and permafrost. J Ecol 100:488–498. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01925.x

Novak K, de Luis M, Cufar K, Raventos J (2011) Frequency and variability of missing tree rings along the stems of Pinus halepensis and Pinus pinea from a semiarid site in SE Spain. J Arid Environ 75:494–498. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.12.005

Polunin N (1955) Attempted dendrochronological dating of ice Island T-3. Science 122:1184–1186. doi:10.1126/science.122.3181.1184

Polunin N (1958) The botany of ice-Island T-3. J Ecol 46:323–347

Poorter H, Niklas KJ, Reich PB, Oleksyn J, Poot P, Mommer L (2012) Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol 193:30–50. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03952.x

Preece C, Phoenix GK (2013) Responses of sub-arctic dwarf shrubs to low oxygen and high carbon dioxide conditions. Environ Exp Bot 85:7–15. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2012.06.003

Rachlewicz G, Styszyńska A (2007) Porównanie przebiegu temperatury powietrza w Petuniabukta i Svalbard-Lufthavn (Isfjord, West Spitsbergen) w latach 2001–2003. Problemy Klimatologii Polarnej 17:121–134

Rachlewicz G, Szczucinski W (2008) Changes in thermal structure of permafrost active layer in a dry polar climate, Petuniabukta, Svalbard. Pol Polar Res 29:261–278

Rayback SA, Henry GHR (2006) Reconstruction of summer temperature for a Canadian high Arctic site from retrospective analysis of the dwarf shrub, Cassiope tetragona. Arct Antarct Alp Res 38:228–238

Rønning OI (1996) The flora of Svalbard Polarhåndbok vol no 10. Norsk polarinstitutt, Oslo

Rossi S, Deslauriers A, Anfodillo T, Carraro V (2007) Evidence of threshold temperatures for xylogenesis in conifers at high altitudes. Oecologia 152:1–12. doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0625-7

Rozema J, Weijers S, Broekman R, Blokker P, Buizer B, Werleman C, El Yaqine H, Hoogedoorn H, Fuertes MM, Cooper E (2009) Annual growth of Cassiope tetragona as a proxy for Arctic climate: developing correlative and experimental transfer functions to reconstruct past summer temperature on a millennial time scale. Glob Change Biol 15:1703–1715. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01858.x

Schmidt NM, Baittinger C, Forchhammer MC (2006) Reconstructing century-long snow regimes using estimates of high arctic Salix arctica radial growth. Arct Antarct Alp Res 38:257–262

Schweingruber FH, Poschlod P (2005) Growth rings in herbs and shrubs: life span, age determination and stem anatomy. For Snow Landsc Res 79:195–415

Schweingruber F, Eckstein D, Serre-Bachet F, Bräker O (1990) Identification, presentation and interpretation of event years and pointer years in dendrochronology. Dendrochronologia 8:9–38

Schweingruber FH, Börner A, Schultze E-D (2011) Atlas of stem anatomy in Herbs, Shrubs and Trees, vol 1. Springer verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg

Shaver GR, Billings WD, Chapin FS, Giblin AE, Nadelhoffer KJ, Oechel WC, Rastetter EB (1992) Global change and the carbon balance of arctic ecosystems. Bioscience 42:433–441. doi:10.2307/1311862

Shaver GR, Bret-Harte SM, Jones MH, Johnstone J, Gough L, Laundre J, Chapin FS (2001) Species composition interacts with fertilizer to control long-term change in tundra productivity. Ecology 82:3163–3181. doi:10.1890/0012-9658

Smith JMB, Klinger LF (1985) Above-ground belowground phytomass ratios in Venezuelan paramo vegetation and their significance. Arct Alp Res 17:189–198. doi:10.2307/1550848

Sturm M, Racine C, Tape K (2001) Climate change—Increasing shrub abundance in the Arctic. Nature 411:546–547

Tape K, Sturm M, Racine C (2006) The evidence for shrub expansion in Northern Alaska and the Pan-Arctic. Glob Change Biol 12:686–702. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01128.x

Thibeault-Martel M, Krause C, Morin H, Rossi S (2008) Cambial activity and intra-annual Xylem formation in roots and stems of Abies balsamea and Picea mariana. Ann Bot-Lond 102:667–674. doi:10.1093/Aob/Mcn146

Walker DA, Raynolds MK, Daniels FJA, Einarsson E, Elvebakk A, Gould WA, Katenin AE, Kholod SS, Markon CJ, Melnikov ES, Moskalenko NG, Talbot SS, Yurtsev BA, Team C (2005) The circumpolar arctic vegetation map. J Veg Sci 16:267–282. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2005.tb02365.x

Walker DA, Epstein HE, Raynolds MK, Kuss P, Kopecky MA, Frost GV, Daniels FJA, Leibman MO, Moskalenko NG, Matyshak GV, Khitun OV, Khomutov AV, Forbes BC, Bhatt US, Kade AN, Vonlanthen CM, Tichy L (2012) Environment, vegetation and greenness (NDVI) along the North America and Eurasia Arctic transects. Environ Res Lett 7(1). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/1/015504

Webber PJ (1977) Below ground tundra research—commentary. Arct Alp Res 9:105–111

Weijers S, Broekman R, Rozema J (2010) Dendrochronology in the High Arctic: July air temperatures reconstructed from annual shoot length growth of the circumarctic dwarf shrub Cassiope tetragona. Quat Sci Rev 29:3831–3842. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.09.003

Weijers S, Alsos IG, Eidesen PB, Broekman R, Loonen MJJE, Rozema J (2012) No divergence in Cassiope tetragona: persistence of growth response along a latitudinal temperature gradient and under multi-year experimental warming. Ann Bot-Lond 110:653–665. doi:10.1093/Aob/Mcs123

Wigley TML, Briffa KR, Jones PD (1984) On the average value of correlated time-series, with applications in dendroclimatology and hydrometeorology. J Clim Appl Meteorol 23:201–213. doi:10.1175/1520-0450

Wilmking M, Hallinger M, Van Bogaert R, Kyncl T, Babst F, Hahne W, Juday GP, de Luis M, Novak K, Vollm C (2012) Continuously missing outer rings in woody plants at their distributional margins. Dendrochronologia 30:213–222. doi:10.1016/j.dendro.2011.10.001

Wils THG, Robertson I, Eshetu Z, Sass-Klaassen UGW, Koprowski M (2009) Periodicity of growth rings in Juniperus procera from Ethiopia inferred from crossdating and radiocarbon dating. Dendrochronologia 27:45–58. doi:10.1016/j.dendro.2008.08.002

Wils THG, Sass-Klaassen UGW, Eshetu Z, Bräuning A, Gebrekirstos A, Couralet C, Robertson I, Touchan R, Koprowski M, Conway D, Briffa KR, Beeckman H (2011) Dendrochronology in the dry tropics: the Ethiopian case. Trees 25:345–354. doi:10.1007/s00468-010-0521-y

Wilson WJ (1957) Observations on the temperatures of arctic plants and their environment. J Ecol 45:499–531

Wipf S (2010) Phenology, growth, and fecundity of eight subarctic tundra species in response to snowmelt manipulations. Plant Ecol 207:53–66. doi:10.1007/s11258-009-9653-9

Woodcock H, Bradley R (1994) Salix arctica (Pall.): its potential for dendroclimatological studies in the high arctic. Dendrochronologia 12:11–22

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Scientific Exchange Program Sciex through the project ArcDendro – Arctic Shrub Dendroecological Potential (grant number 09.045). The polar expeditions in Svalbard were funded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant number N N306 009139). We thank to the Adam Mickiewicz University and the Governor of Svalbard for supporting the expeditions. For valuable comments on the study design and scientific support, we would like to thank Fritz Schweingruber, David Frank, and the “Shrub Hub Community”. We gratefully thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. For the English correction of the manuscript, we are grateful to Silvia Dingwall and Gregory M. King.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Buchwal, A., Rachlewicz, G., Fonti, P. et al. Temperature modulates intra-plant growth of Salix polaris from a high Arctic site (Svalbard). Polar Biol 36, 1305–1318 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-013-1349-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-013-1349-x