Abstract

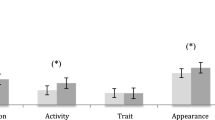

Biological sex has been assumed to be a basic category that importantly influences perceptions people have of others. However, it has recently been proposed that there are individual differences in this presumed generic propensity to use sex in person perception — that some people have schemas with regard to sex and gender, whereas others do not. Prior attempts to demonstrate these differences have frequently operationalized their variables in such a way that activation of hypothesized elaborate and dense gender schemas (schemas relating to psychological masculinity and femininity) could not be disentangled from activation of very shallow schemas related simply to biological sex or sex stereotypes. This study provides initial support for the conceptual distinction between cognitive processing based on biological sex vs. psychological gender. Independent manipulation of both sex-stereotyped information and less salient, nonstereotyped gender-relevant behavioral cues demonstrated that two levels of cognitive operation seem to be used. All subjects, regardless of gender role, used surface information regarding biological sex to make inferences regarding targets' masculinity and femininity. However, only some subjects made use of gender-related behavioral cues when assessing masculinity and femininity on indirect measures. Masculine males demonstrated their expertise in sex appropriateness in judging a male target who behaved sex appropriately, whereas cross-sex-typed subjects demonstrated expertise in sex inappropriateness in judgments of a male target who behaved sex inappropriately. The results are consistent with self-schema theory predictions regarding individual differences in schematic processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Beauvais, C., & Spence, J. (1987). Gender, prejudice, and categorization. Sex Roles, 16, 89–100.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155–162.

Bem, S. L. (1981a). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88, 354–364.

Bem, S. L. (1981b). The BSRI and gender schema theory: A reply to Spence and Helmreich. Psychological Review, 88, 369–374.

Bem, S. L. (1982). Gender schema theory and self schema theory compared: A comment on Markus, Crane, Bernstein, and Saladi's “Self schemas and gender.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1192–1194.

Bem, S. L. (1984). Androgyny and gender schema theory: A conceptual and empirical integration. In T. B. Sonderegger (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Psychology and gender. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Broverman, I. K., Vogel, S. R., Broverman, D. M., Clarkson, F. E., & Rosenkrantz, P. S. (1972). Sex-role stereotypes: A current appraisal. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 59–78.

Crane, M., & Markus, H. (1982). Gender identity: The benefits of a self-schema approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1195–1197.

Deaux, K., & Lewis, L. L. (1984). Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 991–1004.

Deaux, K., Kite, M., & Lewis, L. L. (1985). Clustering and gender schemata: An uncertain link. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 11, 387–397.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1982). Cognitive processes in understanding on-going behavior. In R. Hastie et al. (Eds.), Person Memory: The cognitive bases of social perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Edwards, V. J., & Spence, J. T. (1987). Gender-related traits, stereotypes and schemata. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 146–154.

Frable, D., & Bem, S. L. (1985). If you're gender schematic, all members of the opposite sex look alike. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 459–468.

Gough, H. G. (1986). Correlations of the Fe (femininity) scale of the Revised CPI with self-report and spouse reported acts. Unpublished data.

Gough, H. G. (1987). California Psychological Inventory: Manual (rev. ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Hamilton, D. L. (1979). A cognitive-attributional analysis of stereotyping. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 12. New York: Academic Press.

Hungerford, J. F., & Sobolew-Shubin, A. P. (1987). Sex role identity, gender identity, and self-schemata. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11, 1–10.

Kite, M. E., & Deaux, K. (1987). Gender belief systems, homosexuality, and the implicit inversion theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11, 83–96.

Markus, H., Smith, J., & Moreland, R. (1985). Role of the self-concept in perception of others. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 49, 1494–1512.

Markus, H., Crane, M., Bernstein, S., & Saladi, M. (1982). Self-schemas and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1494–1512.

Mills, C. J. (1983). Sex-typing and self-schemata effects on memory and response latency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 163–172.

Payne, T., Connor, J., & Colletti, G. (1987). Gender-based schematic processing: An investigation and re-evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 937–945.

Ruble, D., & Stangor, C. (1986). Stalking the elusive schema: Insights from developmental and social-psychological analyses of gender schemas. Social Cognition, 4, 227–261.

Skitka, L. J., & Maslach, C. (1988). The spontaneous use of gender as a cognitive schema. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Western Psychological Association, Burlingame, CA.

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1978). Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates and antecedents. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1981). Androgyny versus gender schema: A comment on Bem's gender schema theory. Psychological Review, 88, 365–368.

Spence, J. T., & Sawin, L. L. (1984). Images of masculinity and femininity: A reconceptualization. In V. O'Leary, R. Unger, & B. Wallston (Eds.), Sex, gender, and social psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Stangor, C. (1988). Stereotype accessibility and information processing. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 694–708.

Taylor, S. E., & Falcone, H. (1982). Cognitive bases of stereotyping: The relationship between categorization and prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 8, 426–432.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skitka, L.J., Maslach, C. Gender roles and the categorization of gender-relevant behavior. Sex Roles 22, 133–150 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288187

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288187