Abstract

In advance selling, firms announce that they will charge different prices for those who buy early vs. those who buy late. Previous literature showed that advance selling allows for increased profits in a rather wide range of settings, which typically hold in many service industries. Despite ample evidence that consumers exhibit higher discount rates than firms, it is not clear how differences in time preferences affect optimal prices of advance selling. This article develops an analytical model for optimal prices in advance selling that accounts for such differences in time preferences. In contrast to previous literature, the results indicate that advance selling quickly becomes less profitable than spot selling if consumers discount at a higher rate than firms (and vice versa). They also show that previous findings about the optimality of different advance selling strategies are unaffected if consumers and firms discount at the same rate, despite different optimal prices. Another major implication of our work is that analytical models and managerial decision making should consider time preferences if payment and consumption might occur at different points in time.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In advance selling, firms announce that they will charge different prices for those who buy early vs. those who buy late. Hence, advance selling occurs when consumers can make and pay for purchase commitments before the time of service delivery. In return for an advance purchase commitment—consummated with tickets, tokens, vouchers, passes, or certificates—the consumer receives some benefits. The most common benefits are a price discount and a guaranteed access to the service [1]. In their pioneering work, Shugan and Xie [2] analyze the profitability of advance selling and show that when uncertainty about future consumption states is present in combination with low variable costs, advance selling is more profitable than spot selling. Those two conditions are frequently fulfilled in many service industries [e.g., 3, 4]. Shugan and Xie [2] conclude that advance selling is frequently profitable even in the absence of capacity constraints and a negative correlation between price sensitivity and the time of purchase, which are the profitability drivers of yield management [5]. Shugan and Xie [1] also note that yield management, which is particularly popular in the travel industry, differs from advance selling because prices are dynamic and therefore not announced in advance.

Based on the existing findings, many firms should be able to increase profits by charging different prices for those who buy early (“advance buyers”) and those who buy late (“spot buyers”). Despite these clear recommendations, advance selling is hardly used by firms [6]. For example, prices for tickets for sporting or entertainment events, pay-per-view TV events, amusement parks, ski passes, dinner buffets, and vouchers for taxis or meals barely vary between early and late buyers [7].

An important characteristic of advance selling is that payment occurs before the consumption of the service. This time lag between purchase and consumption suggests that time preferences and the resulting discount rates may affect optimal prices in advance selling. Hence, if firms ignore time preferences in their decision making, they may charge suboptimal prices or even choose a wrong pricing strategy. Although advance selling is well connected to the aspect of inter-temporal choice—firms as well as consumers must decide when they sell or buy—the effect of time preferences on optimal prices and the profitability of advance selling was not analyzed, neither in the seminal paper of Shugan and Xie [2] nor in the extensions of their model [8–12], nor in Sainam, Balasubramanian, and Bayus [13] who analyzed the profitability of advance selling in comparison to option pricing. Consequently, it is not known if different decisions occur in case firms do not ignore time preferences.

Therefore, the aims of this paper are to extend these models by incorporating time preferences that can differ between consumers and firms and to analyze the impact of differences in time preferences on optimal prices and profitability of advance selling. Our results show that time preferences always influence the optimal prices, but the optimality of advance selling is unaffected if consumers and firms discount at the same rate or firms discount at a higher rate than consumers. Yet, the results outline that in the case where consumers have higher discount rates than firms, advance selling quickly becomes less profitable and therefore less attractive than spot selling. Hence, the paper provides one explanation as to why firms hardly charge different prices for early and late buyers, which is in sharp contrast with recommendations of previous studies (for a summary, see [6, 7]).

Higher discounting of consumers than firms seems to be a realistic assumption in the context of advance selling because a wide range of studies in consumer behavior research outline that consumers exhibit fairly high discount rates. For example, consumers’ yearly discount rates are frequently 30 % and higher (see the summaries in [14, 15]). In contrast, firms usually discount at lower rates. The industry average of a firm’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is hardly higher than 11 % (see the available data at the website of professor Damodaran: http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~%20adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/wacc.htm).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. We briefly review the literature on advance selling in Section 2. We present in Section 3 our model setup, which, apart from the consideration of time preferences, corresponds to that previously published in the literature. In Section 4, we analyze the effect of time preferences on the prices and profitability of advance selling for the case of homogeneous consumers. Section 5 investigates the case of heterogeneous consumers. We conclude in Section 6 with implications and limitations of our analysis as well as a discussion of further research.

2 Literature Review

Common to all articles on advance selling is the assumption that purchase decisions are binding, reselling is not possible, and services are offered at posted and similar prices for all consumers. Advance selling then builds upon the idea that buying in advance leads to uncertainty about the value at the time of consumption because a consumer can be in different consumption states at the time of consumption. In line with the state-dependent utility theory (for further details, see [16, 17]), those consumption states are evaluated differently so that the utility from consumption can vary across consumption states even if the quality of the service remains constant. For example, the utility from attending a football match should be greater when a consumer is attending the match with friends than alone or when she/he is in a good instead of a bad state of health. Consequently, the utility a consumer receives from consuming depends on her or his consumption state at the time of service delivery. Buying in advance separates the time of purchase from the time of consumption, which leads to uncertainty about the consumption state and, consequently, customer valuation at the time of consumption, which in turn affects willingness to pay (WTP).

The pioneering work which first analyzed the effect of uncertainty on profitability of advance selling was done by Shugan and Xie [2]. In a simple model with one firm, two periods and two states, they consider consumers that are heterogeneous in their probabilities of being in different consumption states but not in their state-specific WTP. As a result, they show that uncertainty about future consumption states in combination with low variable costs makes advance selling (i.e., selling before the time of consumption) more profitable than spot selling (i.e., only selling at the time of consumption).

Xie and Shugan [12] extend the model of Shugan and Xie [2] in several ways. For homogeneous consumers with and without capacity restrictions, they analyze the effect of differences in arrival time (some consumers are on the market earlier than others) on profitability and find that advance selling is more profitable than spot selling if variable costs are low and if the firm can credibly announce that the spot price will be higher than the advance price. Additionally, they analyze the effect of risk aversion, exogenous seller credibility, and refunds and show that these factors can lead to an even higher profitability for advance selling.

Geng, Wu, and Whinston [10] introduce a resale market into the model of Xie and Shugan [12] and analyze how reselling influences the profit of the firm. They show that reselling does not always reduce the profit. Allowing consumers to resell the service in the advance period can even be beneficial for the firm, if the capacity of the service is limited, the number of buyers with a high valuation is small, and the number of early arrivals is not too large.

Shugan and Xie [11] add competition to the basic model of Shugan and Xie [2] and conclude that competition does not diminish the advantage of advance selling. They also note that in some situations, competition can make advance selling even more profitable. For some settings, Shugan and Xie [11] furthermore show for a monopolistic firm that advance selling is always more profitable for any distribution of consumption states as long as all valuations of consumption states are above variable costs.

Bhargava and Chen [8] also use the basic model of Shugan and Xie [2] but differ in the way they define consumer heterogeneity. In contrast to Shugan and Xie [2], they assume that consumers differ in their state-specific WTP but not in their state-specific probability. In this setting, advance selling does not strictly dominate spot selling in terms of profitability because which strategy is more profitable now depends on the degree of heterogeneity. Advance selling is more likely to be more profitable than spot selling for a high or a low degree of heterogeneity but not for a medium degree of heterogeneity. Additionally, Bhargava and Chen [8] show that differences in arrival time of consumers on the market, which were also considered in Xie and Shugan [12], do not influence this result.

Fay and Xie [9] introduce an additional service into the basic model of Shugan and Xie [2] and analyze a multiservice market. Consumers buy at most one service, and the WTP for each service is uniformly distributed over a consumer-specific interval. Hence, multiple consumption states exist in the spot period, and consumers are heterogeneous in their preferences for the services and consequently in their WTP for each service. Fay and Xie [9] show that advance selling is more profitable than spot selling, if consumers vary highly in their WTP of the preferred service and the differences between the WTPs of the two services are small.

To summarize, the previous findings show that advance selling is more profitable than spot selling in most analyzed scenarios. Yet, none of these previous findings consider the effect of time preferences on the optimal prices and the profitability of advance selling. Research on consumer behavior, however, indicates that the differences between consumers’ and firms’ discount rates are potentially very large. Zauberman et al. [15] show that consumers’ subjective estimates of duration do not accurately map onto objective time when making inter-temporal decisions. Their study outlines discount rates of consumers in the range of 160–313 % for a 3-month delay, 83–100 % for a 1-year-long delay, and 36–46 % for a 3-year-long delay. Similarly, the summary by Frederick, Loewenstein, and O’Donoghue [14] of more than 40 studies outlines high discount rates of consumers that are frequently in the range from 30 to 150 %. These values are substantially higher than the industry average of firms’ WACC, which is hardly above 11 %. Most importantly, these values are even higher for short time ranges like days or weeks so that time preferences are likely to matter even if advance selling occurs just a couple of days before the time of consumption [14].

3 Model Setup

Our model setup follows the one of Shugan and Xie [2]. We assume two periods: period 1 is the advance period, and period 2 is the spot period. Purchases can occur in both periods, but consumption and costs for the firm only occur in the spot period. In this two-period model, a firm has three possible strategies [2]: the firm can offer (and price) the service only in the advance period (advance strategy),Footnote 1 only in the spot period (spot strategy), or differently in both periods (mixed strategy) (Fig. 1).

In line with Shugan and Xie [2], we assume that (1) a monopolistic and risk-neutral firm announces its strategy (when to offer) and all of its prices and (2) the consumers are risk-neutral, buy at most one unit, and maximize their consumer surplus (i.e., the difference between their WTP and the price). Consequently, consumers buy in the period for which their (non-negative) consumer surplus is highest. The optimal prices (and thus profitability) of different strategies depend on the state-specific WTP, the probability of the states, the variable costs per unit, and the discount rates of the consumers and the firm. Since buying in advance leads to consumer uncertainty about the valuation at the time of consumption, consumers form expectations in the advance period about their future valuations based on the expected utility theory [17].

When time preferences are taken into account, the point in time when payments and costs occur becomes important. We assume that payments occur at the time of the purchase commitment. Thus, payments from the advance buyers occur in the advance period (t = 0), whereas payments from the spot buyers and the variable costs of the firm that is associated with the delivery of the service occur in the spot period (t = 1). The firm discounts future revenue (revenue from the sales in the spot period) and variable costs to the time of the advance period at a discount rate i f with the discount factor d f = 1/(1 + i f). In contrast, consumers discount future payments and benefits at the discount rate i c and thus the discount factor d c = 1/(1 + i c). Hence, the firm prefers an earlier payment, whereas consumers prefer a later payment. As consumption always occurs in the spot period, buying in advance leads to an earlier payment, so that consumers discount their WTP.

We present in (1) the profit function of the firm at the time of the advance period so that (possible) revenues of the spot period and the variable costs are discounted. The WTP of a consumer in the same (advance) period is shown in (2).

where

- p AS[SP] :

-

Price in advance [spot] period

- Q AS[SP] :

-

Number of buyers in advance [spot] period

- c :

-

Variable costs

- d f :

-

Discount factor of the firm

- WTPAS, k :

-

WTP of the kth consumer in the advance period

- d c :

-

Discount factor of consumers

- q j, k :

-

Probability of occurrence for the jth state for the kth consumer

- WTPSP, j, k :

-

WTP in the jth state for the kth consumer in the spot period

- J :

-

Index set of states

- K :

-

Index set of consumers

4 Profitability of Advance Selling—Homogeneous Consumers

4.1 Optimal Prices and Profits in Different Seller Strategies

Similar to Shugan and Xie [2], we assume that a monopolistic firm faces a group of N homogeneous consumers who all have just two possible states in the spot period: a favorable (“high”) state in which consumers have a WTP of WTPSP, H and an unfavorable (“low”) state in which consumers have a lower WTP of WTPSP, L (i.e., WTPSP, H > WTPSP, L). The favorable state occurs with probability q H, and the unfavorable state consequently occurs with probability q L = 1 − q H. Consumers are homogeneous in that they have an identical WTP (i.e., WTP j, k = WTP j ) and probability of occurrence in a state (i.e., q j, k = q j ), which lead to an identical WTP for all consumers in the advance period. In contrast, in the spot period, some consumers (q H · N) are in the favorable and some ((1 − q H) ∙ N) are in the unfavorable state so that their WTPs differ in the spot period. In this setting, a firm can choose from the following strategies:

-

The firm can sell to all consumers in the spot period by charging a price that equals the WTP in the unfavorable state.

-

The firm can charge a price in the spot period, which equals the WTP in the favorable state, and thereby only sells to the consumers who are in the favorable state.

-

The firm can sell in the advance period by charging a price that equals the (homogeneous) WTP of all consumers in the advance period (see (2)).

The offering of different prices in each period cannot improve profits because consumers are homogeneous. Table 1 summarizes the strategies and their corresponding optimal prices and profits.

The solutions in Table 1 correspond to the results of Shugan and Xie [2], if d f = d c = 1. As Table 1 shows, the consideration of time preferences only changes the optimal price of the advance selling strategy, which decreases if consumers discount. Hence, the profit of the advance selling strategy decreases if consumers discount. Although the consideration of time preferences does not change the optimal (posted) prices of the spot strategies, it changes the present values of these prices for the firm and so the present values of the profits of the spot strategies, which decline if the firm discounts.

To illustrate the effect of time preferences on optimal prices and profits, we use the numerical example provided by Shugan and Xie [2]. In the example, a firm has a group of 100 homogeneous consumers and has variable costs of zero. For every consumer, both states in the spot period occur with a probability of 0.5, and the WTP in the favorable state is $5, and in the unfavorable state, it is $2. A realistic range of the discount rates of consumers, i c, is given by Frederick, Loewenstein, and O’Donoghue [14], summarizing the estimated discount rates from more than 40 studies. They show that the huge majority of discount rates lie within a range from 11 to 400 % (which corresponds to discount factors, d c, between 0.9 and 0.2). We use this range of discount rates of consumers and discount rates for the firm of 11 % (d f = 0.9) and 43 % (d f = 0.7) in Table 2 to outline the influence that the differences in discount rates have on the optimal strategy. Table 2 shows the optimal (announced) prices and the corresponding profits for the different strategies and discount rates. The first row (i f = 0 %; i c = 0 %) represents the results of Shugan and Xie [2] (no discounting). The fourth (bold) row (i f = 11 %; i c = 56 %) shows the profit of the advance selling, which is in this example equal to the most profitable spot strategy (spot selling to the high price). The last row (i f = 43 %; i c = 11 %) illustrates the consequences for the strategies if the firm discount.s more strongly than the consumers.

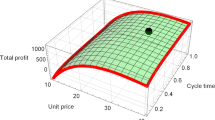

In the case of no time preferences, the firm can improve its profit with advance selling by 40 % (=($350 − $250)/$250). When time preferences are considered, the advance strategy still is best if the discount rates do not differ. If the firm discounts more strongly than the consumers, advance selling improves the profit even more. In contrast, spot selling can become favorable if consumers discount more strongly than the firm and the difference in the discount rates is large enough (see Fig. 2). For a given discount rate of 11 % for the firm (d f = 0.9), spot selling at the high price becomes optimal if the discount rate of consumers becomes higher than 56 % (d c < 0.64). If the probability for the favorable state, q H, rises from 0.5 to 0.8, then the discount rate of consumers required for a change in the optimal strategy decreases from 56 to 22 % (d c < 0.82).

Figure 2 illustrates the results for the comparison between advance selling strategy and spot selling (at a high price) graphically. In relation to spot selling to the high price, advance selling benefits from a larger number of buyers, but suffers from a price that is lower than the spot price. As long as the optimal price of advance selling, respectively its margin, is not too low, advance selling yields a higher profit than spot selling. Consumers’ time preferences have no effect on the optimal spot price, but they affect the optimal advance selling price. The higher the discount rate of consumers, the lower is the optimal price of advance selling (and vice versa). Consequently, if the optimal price of advance selling, respectively the corresponding margin, is too low, the additional buyers in advance selling can no longer compensate the loss in margin, and spot selling becomes more profitable. Thus, we conclude that the consideration of time preferences can easily change the optimal pricing strategy.

4.2 Profit Comparison and Optimality Conditions

We compare in Table 3 the profits of the different strategies (see Table 1) to better outline the influence of time preferences on the optimal strategy and describe the results for all strategies below.

4.2.1 Comparison of the two Spot Strategies (High Spot Price vs. low Spot Price)

As Table 3 shows, differences in the discount rate of consumers and the firm do not influence the profitability of the two spot strategies. The reason is that the payments in both strategies occur at the same point in time. Consequently, the results of Shugan and Xie [2] remain valid for this comparison: no strategy dominates, and the profitability of the strategies depends on the values of the state-specific WTP, the state-specific probability, and the variable costs. The spot strategy with the high spot price thereby benefits from a rising difference in the state-specific WTPs, a rising difference in the state-specific probabilities, and rising variable costs.

4.2.2 Comparison of Advance Strategy with Low Spot Price Strategy

Consistent with Shugan and Xie [2], the advance strategy dominates spot selling at a low spot price when consumers do not discount (i.e., d c = 1) because the WTP in the favorable state is (by definition) higher than in the unfavorable state. However, if consumers discount (i.e., d c < 1), this result no longer holds. Spot selling at a low price realizes a higher profit than advance selling under the following condition (see also Table 3):

According to (3), selling in the spot period at a low spot price instead of selling in the advance period can only be more profitable if consumers discount more strongly than the firm (i.e., d c < d f) because the numerator is smaller than the denominator as WTPSP, H > WTPSP, L. Consequently, the preferable strategy depends on the difference between the discount rates. The required difference in the discount rates for a favorable spot strategy thereby becomes smaller for a decreasing difference of the state-specific WTPs and a decreasing probability of occurrence of the favorable state.

4.2.3 Comparison of Advance Strategy with High Spot Price Strategy

The last row of Table 3 summarizes the results of the profit comparisons of the advance strategy vs. the spot strategy with a high spot price. In the case of no discounting, the results correspond to those of Shugan and Xie [2]. The advance strategy dominates the spot strategy with a high spot price if the variable costs are lower than the WTP in the unfavorable state, which is likely in a wide range of situations as many services have high fixed costs and low variable costs (e.g., [3, 4]). Again, stronger discounting of the firm than consumers is beneficial for the advance strategy, and the advance strategy can even realize the highest profit if the variable costs are above the WTP in the unfavorable state. Yet, spot selling can become more profitable than advance selling if consumers discount strongly. Table 3 shows that spot selling at a high price is more profitable than advance selling if the following condition holds:

As mentioned above, it is very likely that the variable costs are below the WTP in the unfavorable state. But like (4) shows, the spot strategy can lead to higher profits if consumers discount more strongly than the firm. Hence, the difference of the discount rates determines whether spot selling at a high price is more profitable than advance selling. The required difference in the discount rates is smaller if the difference between the state-specific WTPs, the probability for the favorable state, and the variable costs increase.

4.2.4 Optimality Condition of Spot Selling

The conditions under which the two (low and high) spot price strategies become more profitable than advance selling are shown in (3) and (4). As only one of these conditions has to be fulfilled to make spot selling more profitable than advance selling, we can combine (3) and (4) to show under which condition spot selling realizes a higher profit than advance selling:

Equation 5 shows spot selling is getting more attractive the lower the consumer’s discount factor d c = 1/(1 + i c) is compared to the firm’s discount factor d f = 1/(1 + i f). Stated differently, if consumers discount more strongly than firms, i.e., i c > i f, then advance selling is getting less profitable because the price that the firm charges in the advance period will be lower.

5 Profitability of Advance Selling—Heterogeneous Consumers

5.1 Optimal Prices and Profits in Different Seller Strategies

Similar to Shugan and Xie [2], we assume for the case of heterogeneous consumers that a firm faces two groups (A and B) of consumers with an equal size, N, and only two possible states in the spot period. The two groups have an identical WTP for a state (i.e., WTP j, h = WTP j ) but differ in the state-specific probability. As in the homogeneous case, consumers have a WTP of WTPSP, H in the favorable state and a lower WTP of WTPSP, L in the unfavorable state. The favorable state occurs with probability q H, A for group A and with probability q H, B for group B, whereas we assume that for consumers of group A, the probability is higher (i.e., q H, A > q H, B). The unfavorable state occurs with probability q L, A = 1 − q H, A for group A and with probability q L, B = 1 − q H, B for group B. Similar to the homogeneous case, in the spot period, some consumers are in the favorable state ((q H, A + q H, B) · N) and some in the unfavorable state ((2 − q H, A − q H, B) · N). Since the consumer groups differ in their state-specific probabilities, they also differ in their WTP in the advance period. Given these assumptions, the WTP in the advance period is higher for group A than for group B (i.e., WTPAS, A > WTPAS, B).

In this setting, a firm can choose from the three strategies already considered in the homogeneous case (high and low spot price strategies, advance strategy) and a mixed strategy. In the advance strategy, the firm sells to all consumers by charging a price that equals the WTP of group B. In contrast, when using the mixed strategy, the firm charges a higher price in the advance period which equals the WTP of group A. Consequently, only the consumers of group A buy in the advance period. In addition, the firm also sells in the spot period to those consumers of group B who will be in the favorable state. Table 4 summarizes the prices and profits of these four strategies. The solutions in Table 4 correspond to the results of Shugan and Xie [2] if d f = d c = 1.

As in the homogeneous case, time preferences only influence the optimal advance price, which decreases if consumers discount. Consequently, the profits of the advance strategy and the mixed strategy both decrease if the discount rate of consumers increases. Furthermore, the present value of the spot period sales decreases if the firm discounts. Hence, the present values of the profits of the spot strategies as well as present value of the mixed strategy decrease if the firm discounts.

Shugan and Xie [2] also provide a numerical example for heterogeneous consumers, which we use to illustrate the effect of time preferences on the optimal prices and profits. In their numerical example, Shugan and Xie [2] assume two groups with an equal size of one, who differ only in the state-specific probabilities. Consumers have a WTP of $50 in the favorable and $10 in the unfavorable state. For consumers in group A, the favorable state occurs with a probability of 0.4 and the unfavorable state with a probability of 0.6. In contrast, consumers in group B have a state-specific probability of 0.1 for the favorable state and 0.9 for the unfavorable state. For varying discount factors, Table 5 presents the optimal prices and profits for the different strategies. The first row (i f = 0 %; i c = 0 %) represents the results of Shugan and Xie [2], and the fourth (bold) row (i f = 11 %; i c = 45 %) shows the result for which the profits of the mixed strategy and the (high price) spot strategy are the same.

Compared to the best spot strategy, the mixed strategy improves the profit by 24 % (($31 − $25)/$25) and the advance strategy by 12 % (($28 − $25)/$25) if time preferences do not exist. However, the high spot price strategy is optimal if the discount rate of consumers is higher than 45 % (d c < 0.69), a value that is still within the range of results summarized by Frederick, Loewenstein, and O’Donoghue [14]. In contrast, if the firm has a higher discount rate than consumers (i f > i c, thus d f < d c), the spot strategy becomes even less attractive.

5.2 Profit Comparison and Optimality Conditions

In Table 6, we compare the profits of the four strategies, which results in six comparisons. They outline the conditions under which a strategy realizes a higher profit than the one to which it is being compared.

Two comparisons provide no additional information, because the results are not influenced by consumer heterogeneity. In the advance strategy and the low spot price strategy, a firm sells to all consumers and thereby ignores consumer heterogeneity. Hence, the condition is similar to the one in the homogeneous case (see Eq. (3) and second row of Table 6).

Comparing the profits of the mixed strategy to those of the spot strategy with a high price (fifth row of Table 6) shows that consumers of group B have no impact on the difference in profit because it is always treated equally. Thus, this comparison (see Table 6) yields the same results as the comparison of the advance strategy to the high spot price strategy in the homogeneous case (see Eq. (4)).

Furthermore, we already know from the homogenous case that time preferences do not influence the profitability and the comparison of the two spot strategies. We only describe the results for the remaining three comparisons in more detail:

5.2.1 Comparison of the Advance Strategy with the High Spot Price Strategy

Even without considering time preferences, the spot strategy with a high spot price can yield higher profits than the advance strategy, if the variable costs exceed the WTP in the unfavorable state (see Eq. (4)). Incorporating time preferences is beneficial for the spot strategy with a high price if consumers discount more strongly than the firm (i.e., d c < d f) because the profit of the advance strategy will then show a sharper decrease than the profit of the spot strategy with the high price. Spot selling at a high price is more profitable than the advance strategy if the following condition holds (see Table 6):

According to (6), the discount rate of consumers required to make spot selling at a high price more profitable than the advance strategy will increase (d c decreases) if the WTP for the unfavorable state increases, the difference of the group-specific probability decreases, the variable costs decrease, or the discount rate of the firm increases (meaning that the discount factor d f decreases). Note that for this comparison, spot selling at a high price can yield higher profits even when consumers have a lower discount rate than the firm.

5.2.2 Comparison of Mixed Strategy and Low Spot Price Strategy

The comparison of the mixed strategy to the spot strategy with a low spot price (see the fourth row of Table 6) shows that the spot strategy can also become more profitable if time preferences do not exist. The consideration of time preferences is beneficial for the advance strategy if the firm has a higher discount rate than the consumers (and vice versa). If the following condition holds, spot selling at a low price is more profitable than the mixed strategy (see also Table 6):

According to (7), the discount rate of consumers required to make spot selling more profitable than the mixed strategy will increase (d c decreases), if the difference of the state-specific WTPs increases, the group-specific probability for the favorable state increases, the variable costs increase, or the discount rate of the firm increases (d f decreases). As in the previous comparison, the spot strategy can be more profitable even if the firm has a higher discount rate than consumers. Furthermore, spot selling at a low price cannot realize higher profits than the mixed strategy if the numerator becomes negative because in this case only the sales of the mixed strategy in the spot period yield to a higher profit than the spot strategy with a low price.

5.2.3 Comparison of Mixed Strategy and Advance Strategy

Shugan and Xie [2] have already shown that in the absence of time preferences, neither the mixed strategy nor the advance strategy dominates. This result still holds if time preferences exist. Since it is likely that consumers will have a higher discount rate than the firm, the mixed strategy benefits from the consideration of time preferences because not all sales of the mixed strategy occur in the advance period. We present in (8) the condition under which the advance strategy is more profitable than the mixed strategy (see Table 6).

According to (8), the mixed strategy benefits from a decreasing difference in the state-specific WTPs, an increasing difference in the group-specific probabilities for the favorable state, rising variable costs, and an increasing discount rate of consumers (i.e., a decrease in d c). Note that the denominator can become negative. If this is the case, the advance strategy cannot yield to higher profits than the mixed strategy because then the profit from sales in the advance period of the mixed strategy is greater than the profit from the advance strategy.

5.2.4 Optimality Condition of Spot Selling

Spot selling becomes optimal, if one of the possible spot strategies realizes more profit than the advance strategy and mixed strategy. We present in (9) the condition under which spot selling is more profitable than advance selling. An increase in the discount rate of the firm, i f, leads to a decrease of the discount rate, d f, which lowers the value of the right-hand side of (9). In contrast, an increase in the discount rate of the consumers, i c, leads to a decrease of the discount rate, d c, which lowers the value of the left-hand side of (9). Thus, spot selling is getting more profitable than advance selling the more strongly the consumers discount compared to the firm.

6 Summary and Conclusions

Previous research on advance selling recommends firms to charge different prices for early and late buyers, but they ignore time preferences and consequently differences between the discount rate of consumers and firms. Empirical results show that such time preferences exist and that differences in discount rates of consumers and firms can be very high [see 14, 15]. The aims of our paper were to expand previous models on advance selling by time preferences of consumers and firms and to analyze the impact of differences in time preferences on optimal prices and profitability of advance selling. The results are summarized in Table 7 that compares our findings with the conclusions of previous work that did not include time preferences.

The comparison of the columns in Table 7 shows that time preferences very strongly influence the optimality of the different pricing strategies. The results for homogeneous consumers change in two of the three considered cases, and the results for heterogeneous consumers change for two of the six considered cases if consumers discount more strongly than the firm. Additionally, higher discount rates of consumers than firms make advance selling less profitable than spot selling. This result is intuitively appealing because the high discount rate of consumers implies that their early payments need to be compensated by a lower price. A firm which ignores time preferences then overestimates the profit of advance selling and may choose the wrong pricing strategy.

Therefore, our results are contrary to the previous findings that state that uncertainty about the future consumption state alone is frequently sufficient to ensure the superiority of advance selling. We outline that this finding is unlikely to hold if consumers discount more strongly than firms. As there is ample evidence that consumers discount more strongly than firms, our findings also provide one explanation for the observation that prices (e.g., for tickets of sporting or entertainment events, pay-per-view TV events, cloud computing, and vouchers for taxis or meals) barely vary between early and late buyers [6, 7].

Additionally, our results outline that higher discounting of firms than that of consumers makes advance selling more attractive. Although such a setting is usually not observed empirically, it might occur if a firm has financial problems and a high preference for receiving money quickly. In such a case, advance selling can be even more profitable if the variable costs are high, which is in contrast to the results of previous research. Based on the assumptions, the costs occur at the point of service delivery (the spot period). Hence, firms also discount the variable costs and use its present value in their calculations, which makes advance selling more attractive.

Finally, our results show that all previous findings about optimal pricing strategies hold if discount rates of the firm and consumers are equal. Still, firms should consider time preferences. If they exist, then they always affect the optimal advance price. Hence, a major implication of our work is also that firms (and studies) should consider time preferences if payment and consumption might occur at different points in time.

Our research also contains limitations, which suggest opportunities for additional research. First, we develop an analytical model that provides evidence as to why advance selling can easily be less profitable than spot selling. More empirical support would certainly be helpful, but it is also difficult to obtain because few examples of advance selling exist, making empirical data scarce.

Second, the major results of the paper build upon the assumption that consumers exhibit higher discount rates than firms. Although there is quite some evidence that this assumption holds, we cannot provide empirical support in this paper, and we cannot outline the specific reasons why consumers have such high discount rates.

Third, we focus on a monopolistic setting, which is the setting that is most profitable for the firm. We show for this fairly favorable setting for the firm that advance selling is less profitable than spot selling if consumers discount much more strongly than the firm. The analysis of Shugan and Xie [11] for a competitive setting without time preferences indicates that the formal analysis of this setting is very complex but the basic results of the monopolistic setting still hold [6]. Future research should prove if our main conclusion, i.e., that stronger discounting by consumers than by the firm makes advance selling less attractive, also holds in a competitive setting.

Notes

This strategy is similar to a strategy in which the service is offered in both periods, but because the price is very high in the spot period, consumers would never buy in the spot period. The same argument holds for the spot strategy.

References

Shugan SM, Xie J (2004) Advance selling for services. Calif Manag Rev 46(3):37–54

Shugan SM, Xie J (2000) Advance pricing of services and other implications of separating purchase and consumption. J Serv Res 2(3):227–239

Guiltinan JP (1987) The price bundling of services: a normative framework. J Mark 51(2):74–85

Shapiro C, Varian HR (1998) Information rules: a strategic guide to the network economy. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Desiraju R, Shugan SM (1999) Strategic service pricing and yield management. J Mark 63(January):44–56

Xie J, Shugan SM (2009) Advance selling theory. In: Rao V (ed) Handbook of pricing research in marketing. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton, pp 451–476

Moe WW, Fader PS (2009) The role of price tiers in advance purchasing of event tickets. J Serv Res 12(1):73–86

Bhargava HK, Chen RR (2012) The benefit of information asymmetry: when to sell to informed customers? Decis Support Syst 53(2):345–356

Fay S, Xie J (2010) The economics of buyer uncertainty: advance selling vs probabilistic selling. Mark Sci 29(6):1040–1057

Geng X, Wu R, Whinston AB (2007) Profiting from partial allowance of ticket resale. J Mark 71(2):184–195

Shugan SM, Xie J (2005) Advance-selling as a competitive marketing toll. Int J Res Mark 22(3):351–373

Xie J, Shugan SM (2001) Electronic tickets, smart cards, and online prepayments: when and how to advance sell. Mark Sci 20(3):219–243

Sainam P, Balasubramanian S, Bayus B (2010) Consumer options: theory and an empirical application to sports market. J Mark Res 47(3):401–414

Frederick S, Loewenstein G, O'Donoghue T (2002) Time discounting and time preference: a critical review. J Econ Lit 40:351–401

Zauberman G, Kyu Kim B, Malkoc SA, Bettmann JR (2009) Discounting time and time discounting: subjective time perception and intertemporal preferences. J Mark Res 46(4):543–556

Cook PJ, Graham DA (1977) The demand for insurance and protection: the case of irreplaceable commodities. Q J Econ 91(1):143–156

Fishburn PC (1974) On the foundations of decision making under uncertainty. In: Balch M, McFadden D, Wu S-Y (eds) Essays on economic behavior under uncertainty. North-Holland Pub, Amsterdam, pp 25–44

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schaaf, R., Skiera, B. Effect of Time Preferences on Optimal Prices and Profitability of Advance Selling. Cust. Need. and Solut. 1, 131–142 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40547-014-0009-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40547-014-0009-9