Abstract

Purpose

Food waste treatment methods have been typically analysed using current energy generation conditions. To correctly evaluate treatment methods, they must be compared under existing and potential decarbonisation scenarios. This paper holistically quantifies the environmental impacts of three food waste downstream management options—incineration, composting, and anaerobic digestion (AD).

Methods

The assessment was carried out using a novel hybrid input–output-based life cycle assessment method (LCA), for 2014, and in a future decarbonised economy. The method introduces expanded system boundaries which reduced the level of incompleteness, a previous limitation of process-based LCA.

Results

Using the 2014 UK energy mix, composting achieved the best score for seven of 14 environmental impacts, while AD scored second best for ten. Incineration had the highest environmental burdens in six impacts. Uncertainties in the LCA data made it difficult determine best treatment option. There was significant environmental impact from capital goods, meaning current treatment facilities should be used for their full lifespan. Hybrid IO LCA’s included additional processes and reduced truncation error increasing overall captured environmental impacts of composting, AD, and incineration by 26, 10 and 26%, respectively. Sensitivity and Monte Carlo analysis evaluate the methods robustness and illustrate the uncertainty of current LCA methods. Major implication: hybrid IO-LCA approaches must become the new norm for LCA.

Conclusion

This study provided a deeper insight of the overall environmental performance of downstream food waste treatment options including ecological burdens associated with capital goods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In November 2016, 194 countries signed the world’s first comprehensive climate agreement in Paris. This agreement has been adopted overwhelmingly to tackle climate change by introducing binding emissions targets (United Nations 2015; European Commission 2016). Food waste has been identified as a major contributor to climate change with 8% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) which is attributed to improper food waste management (FAO 2013).

In spite of various efforts to reduce food waste arisings per capita, quantities of food waste continue to increase due to population growth. In spite of the UK success in introducing intervention programmes that have reduced food waste arisings per capita by 24%, the overall household food waste arisings in the UK have flat lined at around 7 million tonnes per year, with further large-scale reductions not yet possible (Parry 2014; Quested and Andrew 2017). As food waste is unlikely to be significantly reduced in the short term, greater efforts must be made to reduce its environmental impacts. This could be achieved by first quantifying environmental burdens associated with food waste treatment, identifying processes with the highest environmental impacts (i.e., hotspot analysis) and finally introducing measures to mitigate these impacts.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic approach that is widely used to evaluate the environmental impacts of food waste treatment options (Morris et al. 2013; Laurent et al. 2014a, b). A standardised method prescribed by the International Organisation for Standardization (BSI 2006), LCA, adopts a process-based modelling approach where a system is modelled using an inventory of processes representing inputs, outputs and potential environmental burdens of the system. The literature is abundant with studies that have used LCA to assess different food waste treatment options. However, a comparison of the results is difficult due to difference in methodological approaches, functional units, system boundaries, and variation in waste composition and geographical coverage (Khoo et al. 2010; Fruergaard and Astrup 2011; Boldrin et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2011; Grosso et al. 2012; Evangelisti et al. 2014; Laurent et al. 2014a; Eriksson et al. 2015; Buratti et al. 2015; Ahamed et al. 2016; Jeswani and Azapagic 2016; Bernstad Saraiva Schott et al. 2016).

In addition, reviewed studies suffer from inconsistency and significant variations in results (Cleary 2009; Bernstad and la Cour 2012). The inconsistency observed in food waste management LCA studies can be attributed to several LCA methodological and data-related limitations (Heijungs and Guinée 2007; Cleary 2009; Curran 2012). One of the main drawbacks of conventional process-based LCA is the difficulty of drawing a comprehensive systematic boundary around the studied system which ensures the full inclusion of all components of the system, including both direct and indirect processes. Therefore, the cutoff criteria in system boundaries could potentially lead to system incompleteness, alternatively referred to as truncation error (Suh et al. 2006). The degree of incompleteness varies with the type of system, but it can reach up to 50% in some cases (Lenzen 2001; Suh et al. 2006). Moreover, the results of studies by Lenzen (2001), and Miller and Blair (2009) suggest that even extensive process-based inventories for complex systems fail to include all direct and indirect environmental impacts.

Another factor that is often overlooked and which leads to large variations and substantial underestimations in results is the exclusion of environmental impacts associated with capital goods, a term commonly used to refer to goods, services and energy inputs required at the construction stage of a food waste treatment facility such as composting and anaerobic digestion plants and associated infrastructure. According to a review study, 88% of waste management-LCA studies exclude capital goods. Even more concerning is that 26% of these studies claim that capital goods have insignificant environmental impacts (Laurent et al. 2014a, b).The few studies which did investigate the environmental impacts of capital goods concluded that they could constitute 20% of the total environmental life cycle impacts and contribute substantially to various environmental impact categories such as abiotic resource depletion, climate change, and toxicity (Finnveden et al. 2005; Frischknecht et al. 2007; Brogaard and Christensen 2016).

To counter limitations of LCA, this study adopts a state-of-the-art approach to providing a gate-to-grave assessment of the processing of 1 tonne of household food waste (the functional unit of the study) in the UK using three well-established downstream management options: incineration; composting; and anaerobic digestion (AD). A hybrid input–output-based life cycle assessment, developed by Salemdeeb et al. (2017), was adopted in order to expand system boundaries to include capital goods and reduce truncation error. This paper then uses Monte Carlo analysis to investigate the impact of using different energy mixes (including 100% renewable energy sources) on the overall impacts.

Materials and methods

This section provides description into a novel hybrid LCA method (Sect. 2.1), lists the waste treatment assumptions and system boundaries (Sect. 2.2), outlines the life cycle inventory data sources and compilation methodology of the LCA (Sect. 2.3 and 2.4) and finally describes the methods and materials used for the sensitivity analysis, namely Monte Carlo analysis and energy use scenario analysis (Sect. 2.5 and 2.6).

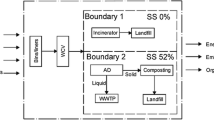

The hybrid IO-LCA model

The hybrid model was developed in accordance with ISO 14040 (BSI 2006). It consists of four stages: (1) defining the goal and scope of the analysis, (2) conducting an inventory analysis, (3) aggregating inventory results into pre-defined environmental and health impact categories, and (4) interpreting the analysis results. Figure 1 illustrates the main components of the hybrid model and depicts how the IO element was integrated into the basic ISO 14040 LCA schematic process. Additional information on the hybrid IO-LCA model is provided in the online accompanying appendix.

As the hybrid LCA model combines models, two types of data are required: physical data (used to model major processes such as energy input); and monetary data (used to address the gap in inventory data and model processes—usually minor—that could have not been modelled using physical data due to the scarcity of data). These are introduced in Sect. 2.3, with further discussion provided in the online accompanying appendix (Appendix 1).

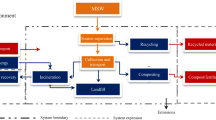

Waste treatment scenarios

The analysis adopts an expanded system boundary including the construction, operation, maintenance, and decommissioning stages. The time horizon boundaries are defined by the lifespan of the waste management facility: 15 years for composting and 20 years for incineration and AD. The disposal of food waste packaging is excluded due to its insignificant impact (Lebersorger and Schneider 2011; Bernstad Saraiva Schott and Andersson 2015). Diagrams depicting system boundaries of the study options are provided in the online appendices (Figures A.2–A.4). Food waste composition (and moisture content) was defined as the average of the three previous UK compositional analyses (Banks et al. 2011, WRAP 2010, and Zhang et al. 2013) (Table A.7).

Composting

Composting is a long-established technology in the UK which is used comprehensively to treat both food and garden waste, providing a valuable fertiliser as a final output. A standard in-vessel composting process consists of three main stages. Before the food waste is processed, it enters the reception building in order to be shredded. Then, the shredded waste is transferred to stage 1 tunnels where it is aerated for 2–3 weeks. The process should achieve at least 60 °C for 48 continuous hours in order to comply with Animal By-Products Regulations. Sanitised compost is then transferred to stage 2 tunnels where the same programme is repeated. Finally, it is transferred to the maturation pad where the final product is screened and prepared for amenity or agricultural use (Hall et al. 2014). The compost utilisation efficiencies used are: 20% for N, 100% for P, and 100% for K (Andersen et al. 2010) and the compost is considered to be applied on loam soil.

Incineration

A combined heat and electricity (moving grate) incinerator was considered in this study. Gross electricity and heat efficiency considered are 13 and 26%, respectively. Although not a common practice in the UK, combined heat and power technology was considered due to its potential to contribute to the UK’s 2020 renewable energy target (ECCC 2016). This assumption is also consistent with recent studies that have investigated the environmental impacts of incinerators in a UK context (Nixon et al. 2013; Jeswani and Azapagic 2016). Additional information on the moving grid incinerator is provided in the appendix.

Anaerobic digestion

Food waste is assumed to be shredded, sieved and then sent to a digestion tank. The output of this biological process is two valuable products: biogas which may be used for either heat or power generation; and digestate that may be utilised as a soil fertiliser (Hall et al. 2014). The anaerobic digestion process involves the breakdown of biodegradable material by micro-organism bacteria in an anaerobic and enclosed environment. As with composting, the anaerobic digestion process must comply with BSI PAS 100 and compost should meet “Quality Control for Compost” requirements (Environment Agency 2010). The digestate substitutes nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium fertilisers with an efficiency of 34.5, 46 and 60%, respectively. Benefits from the contribution made by sulphur, magnesium, and other organic compounds in compost are excluded due to the lack of data (Wallace 2011).

Life cycle inventory data

Monetary data

A thorough literature review, coupled with surveys and personal communications with operators of food waste facilities, was conducted to collect data on expenditure associated with technologies considered. Three leading UK waste management operators were included; these have not been referenced further due to commercial sensitivity. These compiled data were validated and cross-checked with each set to ensure it is representative of those scenarios considered. The data were converted into a basic price in order to match the input output analytical table format. Conversion coefficients used were obtained from Salemdeeb et al. (2016).

The final expenditure of the scenarios, reported in basic price and formatted according to the UK IO format, is available in the online appendix (Table A.2). The breakdown expenditure shows that the majority of the budget is allocated to construction activities; construction expenditure for compost, AD and incineration constitute up to 30, 40 and 60% of the total expenditure, respectively.

Physical data

Physical data, listed in Table 1, were either compiled or calculated based on the information from project documents, literature, or the WRATE database. Upstream and downstream material flows and emissions were collected using existing databases, primarily the Swiss ecoinvent database v2.2 (Econinvent 2014). Capital goods consumed at the construction stage of investigated technologies are also included. Tables that list approximate quantities of capital goods consumed in the construction stage and a list of ecoinvent processes used can be found in the online accompanying appendix.

Life cycle impact assessment

Emissions are aggregated into 14 environmental and health impact categories. Aggregated results were normalised in order to allow for a comparative analysis of the relative importance of each impact category (Table A.6 in the online accompanying appendix). The global warming potential and particulate matter emissions from recycling 1 tonne of food waste are, for example, scaled relative to the per capita greenhouse gas and particulate matter emissions in the year 2010 (and are reported in units of milli-Person equivalents, mPE). Normalisation factors were derived from the PROSUITE project which was developed specifically for the ILCD method (Blok et al. 2013).

Sensitivity analysis

The study follows a four-step sensitivity analysis approach based on Clavreul et al. (2012). For each food waste disposal technology, stages with the highest environmental burdens were identified using a hotspot analysis. The sensitivity of parameters within key stages was investigated by a perturbation analysis. The sensitivity ratio is calculated using Eq. 1 for all parameters, by varying each parameter by ± 10%. Parameters with the highest sensitivity ratio were selected.

Probability distribution coefficients were then assigned to parameters with SR > 2 based on the literature and the results of the “Pedigree quality matrix”, an Ecoinvent-recommended method used to check the reliability and robustness of the model created by Weidema and Wesnæs (1996). Table 2 lists sensitivity analysis parameters for all scenarios.

A Monte Carlo analysis was then performed to generate confidence intervals. For each metric, the significance of differences between technologies was also tested using the Monte Carlo method. The model randomly sampled estimates of the mean for each technology and calculated the difference between each, repeating this resampling 1000 times. The analysis tests the possibility of difference between technologies to overlap with zero at a 99% confidence level.

Energy use scenarios

Four electricity-input scenarios were modelled to investigate changes that result due to future policy decisions and energy technology development (Fig. 2). The baseline scenario represented the 2014 UK electricity national grid (DECC 2014). The other three scenarios (scenarios two to four) are based on potential electricity mix pathways (Stamford and Azapagic 2014): scenarios two and three are based on the decarbonisation of electricity by 65% by 2050 (i.e. Ref (65-A) without nuclear energy, and Ref (65-B) with nucelar energy); and scenario four includes 100% of renewable energy with nuclear energy (40%) and offshore wind (23%) (Ref 100). The values used in each electricity mix pathway scenario are based on the average contribution of each energy source to each scenario from 2014 to 2070. As each scenario is the average energy generation mix for this scenario from 2014 to 2070, there is some coal and other non-renewable contribution to the (Ref 100).

Electricity-input scenarios considered in this study, adapted from Stamford and Azapagic (2014). The figure above shows the average contribution of each energy source to each scenario from 2014 to 2070

Results and discussion

The results of the analysis are summarised in Fig. 3. Overall, composting achieved the best score for 7 out of 14 environmental and health impacts, while AD had the highest environmental burden in 6 impacts and the mean ranking of the three scenarios (1 = best, 3 = worst) were compost: 1.7, AD: 2.1, and incineration: 2.3. A hotspot analysis that shows the contribution of different life cycle stages of each scenario is shown in Fig. 4.

The normalised environmental and health impacts of three food waste downstream technologies: incineration, composting and AD. Units (mPE) relate a process’ emissions in relation to per capita emissions in the EU in 2010. GWP global warming potential, ODP ozone depletion, HT-C emissions of carcinogens, HT-NC emissions of non-carcinogenic toxins, IR ionising radiation, POF photochemical oxidant formation, FEP freshwater eutrophication, MEP marine eutrophication, ET eco-toxicity, ADP-F depletion of fossil fuels, ADP-E depletion of non-fossil fuel abiotic resources, AP terrestrial acidification, TEP terrestrial eutrophication, PM particulate matter emissions. Error bars show one standard deviation

Hotspot analysis of the analysis results for incineration (a), composting (b), and AD (c).Abbreviations are as follows: GWP global warming potential, ODP ozone depletion, HT-C emissions of carcinogens, HT-NC emissions of non-carcinogenic toxins, IR ionising radiation, POF photochemical oxidant formation, FEP freshwater eutrophication, MEP marine eutrophication, ET eco-toxicity, ADP-F depletion of fossil fuels, ADP-E depletion of non-fossil fuel abiotic resources, AP terrestrial acidification, TEP terrestrial eutrophication, PM particulate matter emissions

For composting, the operation stage contributed the most to the majority of impacts, in particular depletion of fossil fuels (60%), terrestrial acidification (60%), terrestrial eutrophication (80%), and ozone depletion (90%). The environmental impacts of compost could be offset by its use as a substitute to synthetic fertiliser, the most significant being climate change (55%), freshwater eutrophication (95%), depletion of abiotic resources elements (48%). The treatment of food waste contributes to the majority of environmental burdens associated with AD. These impacts are attributed primarily to two processes, namely the use of auxiliary materials and wastewater treatment. Construction has a slight impact especially regarding eco-toxicity at 17% and carcinogenic human toxicity carcinogenic at 30%. Most burdens are offset by the use of recovered energy to substitute conventional energy sources (i.e. natural gas and coal).

Incineration has a similar environmental hotspot source to those of composting and AD: operation is the stage with the highest environmental burden while energy recovery (both heat and electricity) plays a key role in offsetting these burdens. The significant contribution from operation is the auxiliary materials used in order to control emissions, ammonia injection to control NOx emissions, lime for control of SO2 and HCL and activated carbon to capture heavy metals.

The supremacy of composting’s results in the majority of the investigated impacts is largely due to the nature of composting itself: it is a technologically simple process that requires considerably low energy and auxiliary material inputs compared to either AD or incineration. In addition, the analysis results show that the majority of the burden in AD and incineration is associated with the treatment of by-products, namely wastewater and methane purification for AD, and Air Pollution Control (APC) for incineration.

The exclusion of the impacts of food collection and transportation in this study also works in favour of composting and AD, as these options require a separate collection system of food waste and, therefore, additional energy input. When treated via incineration, food waste is co-collected and does not require an additional separate food waste collection system. Therefore, incineration consumes less energy input compared to composting and AD. Food collection and transportation are significant for the depletion of fossil fuels, elements, and the ozone layer (Jeswani and Azapagic 2016). A separate food collection system would increase the environmental burden across these categories (Burnley et al. 2011). The lack of food collection and transportation in this study is due to this study being a gate-to-grave assessment, meaning food waste collection and transportation were not included in the analysis. This was due to the fact that the goal of the assessment was to investigate the environmental impacts of food waste management technologies rather than that of the overall waste management system. Future studies could include this larger system boundary in their analysis.

Although the results of the analysis tend to show that composting is more environmentally friendly than other options, it performs worse than AD in two key environmental impacts: climate change and depletion of fossil fuels. This is attributed primarily to the fact that, unlike AD and incineration options, composting process does not include the generation of energy (in the form of electricity or heat) and, therefore, does not offset the huge quantities of emissions as AD and incineration do. The management of 1 tonne of food waste in a composting facility could emit 74 kg CO2-eq./FU while the AD and incineration options achieve significant benefits for the same functional unit; estimated average reductions in AD and incineration being − 2400 kg CO2-eq. and − 3000 kg CO2-eq., respectively. This unsurprising result is attributed to the fossil fuel energy substituted by the production of energy (in the form of electricity, heat, or both) in both AD and incineration options. If a decarbonised energy mix is substituted, the impacts of composting are reduced.

We have assumed the composition and water content of UK food waste via previous studies (Table A.7). As the UK decarbonises, the UK diet may change. This may affect the quality of UK food waste as a feedstock—specifically the water content. A variation in water content will have a large impact on the three treatment methods studied. In case of Incineration, there might not be any positive energy output if the moisture content of food waste goes beyond 50% since more energy is spent in drying which would directly affect the ADP-F (Fig. 3). Similarly the C, H, N, O, S ratio will also have their direct impacts on the environmental benefits and burdens studied here. Future studies could further modify UK food waste and energy generation to match dietary transition.

This study has also not included a comparative cost analysis of the different treatment methods to complement its environmental analysis. Future research could provide a comparative cost analysis of treatment methods under existing and potential decarbonisation scenarios. Furthermore, the study covers three well-established treatment technologies; other food waste treatment technologies are in their “infancy” in the UK waste market and therefore have been excluded. Future research could also broaden scope to compare other waste treatment methods under existing and potential decarbonisation scenarios.

Hybrid LCA vs truncation error

The results of the study demonstrate the ability of the hybrid LCA model to include additional processes and, therefore, reduce truncation error, compared to a conventional process-based LCA method. The adoption of the hybrid model increases estimates of associated GHG emissions with composting, AD and incineration by approximately 26, 10 and 11%, respectively. Thus, the analysis results quantitatively confirm the ability of the hybrid model to reduce truncation error by expanding boundaries of the modelled scenario (Finnveden et al. 2009; Jeswani et al. 2010).

Additional environmental burdens captured are mainly associated with managerial and indirect services such as services of head offices, consulting services, third-party technical services, and testing and maintenance services. These service-based activities are difficult to model using LCA (and, therefore, ignored in the literature), yet contribute substantially to the overall environmental impacts of modelled scenarios. The hybrid model uses the expenditure cost of these activities to estimate their environmental impacts. These expenditure costs are estimated to constitute up to 12% for AD, 10% for compost and 34% for incineration in the construction stage. Expenditure on these services increases for day-to-day operation activities; it accounts for 40% of total expenditure on AD, 67% for compost and 44% for incineration.

The environmental impacts of capital goods

Results show that capital goods constitute up to 20% of the overall environmental impacts in 10 categories for compost and 4 categories for both AD and INC. The study findings support those of previous studies highlighting the significant environmental impacts of capital goods (Finnveden et al. 2005; Brogaard and Christensen 2016). The overall environmental burdens associated with capital goods are presented in Figure A.5.

Capital goods used for the composting scenario contributed mostly to the potential impacts on carcinogenic human toxicity (70%), climate change (45%) and eco-toxicity (40%). These impacts were caused primarily due to the use of cement and steel: the energy input in the production stage of these products contribute the most to climate change while the disposal of steel and cement slag is responsible for the emission of heavy metals and, therefore, contributes to both human toxicity and eco-toxicity (Burchart-Korol 2013; Salas et al. 2016). Significant toxicity impacts are also reported in AD and incineration due to capital goods. The production of steel contributes to both human toxicity and eco-toxicity by 50 and 45% for AD and 13 and 10% for incineration, respectively. In addition, a substantial impact on depletion of abiotic resources (elements) is estimated for both AD and incineration scenarios. This could be explained by the huge quantities of capital goods (in particular steel) required in the construction stage of AD and incineration as these infrastructures are large-scale construction projects compared to composting (Brogaard and Christensen 2016). Significant results were also reported in freshwater eutrophication impacts, in particular in the incineration scenario. This highest impact across all 14 environmental and health categories is caused by excessive use of copper, stainless steel and cement. This finding agrees with those of Brogaard and Christensen (2016) that report a 90% freshwater eutrophication impact due to capital goods.

Comparison with previous literature

Figure 5 provides comparison of ten LCA studies (including this study), reporting greenhouse gas emissions per tonne of food waste processed. The previous studies reported a large variation in the GWP and some broad patterns emerge. Four out of six studies conclude that incineration with energy recovery has the greatest environmental benefits while only two studies conclude in favour of AD. This could be explained due to the high energy input required to operate an AD facility (compared to incineration) and the additional diesel consumption required to set up a separate food waste collection system (Burnley et al. 2011). In addition, variations in the biogas yield and the type of substituted energy adopted in reviewed studies contribute significantly to these discrepancies. For example, Eriksson et al. (2015) reports AD results which are 4 times larger than those reported in this study. This substantial difference could be attributed due to the assumption made by Eriksson and his colleagues that the entire theoretical yield of biogas was produced, while this study is based on actual AD plant figures (see Table 2) Eriksson et al.’s study also assumes that biogas replaces diesel as a fuel for city buses, while this study assumes biogas substitutes UK electricity production by natural gas (61.5%) and coal (38.5%).

Results of ten LCA studies (including this study: the energy mix from 2010 (Ref 2010), and 100% of renewable energy with nuclear energy (Ref 100)) reporting greenhouse gas emissions per tonne of food waste. Crosses are marked where a study has not included a technology in their analysis. Where a study reported several scenarios for the same option, the mean value for all scenarios is shown. The averaged Monte Carlo results of this study are shown with bars showing the maximum and minimum results found by Monte Carlo analysis

Robustness of results

The sensitivity of results was investigated by way of a Monte Carlo Analysis. Overall results, listed in Table 3 below and plotted as error bars in Fig. 3, reveal a high level of uncertainty that could lead to a change in the ranking of scenarios in 7 impact categories between AD and incineration, 4 impact categories between AD and composting, 6 impacts between incineration and composting, and 2 impact categories amongst all scenarios studied (i.e., freshwater eutrophication and ozone depletion). The high level of uncertainty makes it difficult to draw a generic conclusion. However, this study has helped to better understand environmental impact patterns. This analysis also highlights the importance of the quality of data used in order to conduct an environmental assessment of a specific technology.

Notwithstanding the large variability in some parameters as shown in Table 3, the indicator values for all metrics are statistically significant from one another (p < 0.01), except for the effect of composting and anaerobic digestion on marine eutrophication and non-carcinogenic toxicity.

Scenario analysis

Results indicate that the decarbonisation of the UK supply electricity mix leads to reduction in overall environmental burdens across impact categories (Fig. 6). Scenario 4 (Ref100) has reduced the overall impact of global warming potential (GWP) by 82%, while scenario 2 (Ref 65-A) leads to 50% reduction. With regard to Scenario 3 (Ref 65-B), the substitution of natural gas by nuclear energy as a source of low-GHG energy leads to an additional 16% reduction in GWP but does increase the environmental burden in four impact categories: non-carcinogenic human toxicity, ionising radiation (IR), depletion of elements (ADP-E) and particulate matter.

Normalised environmental burdens of different energy scenarios: 2010 UK electricity mix (Ref 2010), 65% of renewables without nuclear energy (Ref 65-A), and with nuclear energy (Ref 65-B), and 100% of renewable energy with nuclear energy (Ref 100). Abbreviations are listed under Fig. 3

Conclusion

This study introduced a novel hybrid IO-LCA model to evaluate the environmental impacts of downstream waste management infrastructure as they operate currently, or as they could operate under future decarbonised energy use scenarios. Results provided a deeper insight into the overall environmental performance of downstream food waste treatment options. More importantly, the study shows how the decarbonisation of the UK national grid would make composting to look a more attractive treatment option than incineration and AD. The results of this study demonstrate the superiority of hybrid IO LCA as it includes additional processes and reduces truncation error increasing overall captured environmental impacts of composting (26%), AD (10%), and incineration (11%). In addition, the study confirms the significant importance of including capital goods in the list of overall environmental impacts and expanding the system boundaries of the system using hybrid LCA analysis.

References

Ahamed A, Yin K, Ng BJH et al (2016) Life cycle assessment of the present and proposed food waste management technologies from environmental and economic impact perspectives. J Clean Prod 131:607–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.127

Andersen JK, Boldrin A, Christensen TH, Scheutz C (2010) Greenhouse gas emissions from home composting of organic household waste. Waste Manag 30:2475–2482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.07.004

Banks CJ, Zhang Y, Walker M (2011) Optimising processes for the stable operation of food waste digestion: technical report Defra WR1208. Department for Communities and Local Government

Bernstad A, la Cour Jansen J (2012) Review of comparative LCAs of food waste management systems—Current status and potential improvements. Waste Manag 32:2439–2455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2012.07.023

Bernstad Saraiva Schott A, Andersson T (2015) Food waste minimization from a life-cycle perspective. J Environ Manage 147:219–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.048

Bernstad Saraiva Schott A, Wenzel H, la Cour Jansen J (2016) Identification of decisive factors for greenhouse gas emissions in comparative lifecycle assessments of food waste management—An analytical review. J Clean Prod 119:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.079

Blok K, Huijbregts M, Roes L, et al (2013) Development and application of a standardized methodology for the PROspective SUsta İ nability assessment of TEchnologies (PROSU İTE) Report prepared within the EC 7th Framework Project, no: 227078. European Commission, Brussels

Boldrin A, Neidel TL, Damgaard A et al (2011) Modelling of environmental impacts from biological treatment of organic municipal waste in EASEWASTE. Waste Manag 31:619–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.10.025

Brogaard LK, Christensen TH (2016) Life cycle assessment of capital goods in waste management systems. Waste Manag 56:561–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.07.037

BSI (2006) BS EN ISO 14044: environmental management—Life cycle assessment—requirements and guidelines. British Standards Institution, London

Buratti C, Barbanera M, Testarmata F, Fantozzi F (2015) Life cycle assessment of organic waste management strategies: an Italian case study. J Clean Prod 89:125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.012

Burchart-Korol D (2013) Life cycle assessment of steel production in Poland: a case study. J Clean Prod 54:235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.04.031

Burnley S, Phillips R, Coleman T, Rampling T (2011) Energy implications of the thermal recovery of biodegradable municipal waste materials in the United Kingdom. Waste Manag 31:1949–1959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.04.015

Clavreul J, Guyonnet D, Christensen TH (2012) Quantifying uncertainty in LCA-modelling of waste management systems. Waste Manag 32:2482–2495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2012.07.008

Cleary J (2009) Life cycle assessments of municipal solid waste management systems: a comparative analysis of selected peer-reviewed literature. Environ Int 35:1256–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2009.07.009

Curran MA (2012) Life cycle assessment handbook: a guide for environmentally sustainable Products, 1st edn. Scrivener Publishing LLC, Massachusetts

DECC (2014) Digest of United Kingdom energy statistics (DUKES). In: Department of Energy Climate Change

ECCC (2016) 2020 renewable heat and transport targets. House of Commons, London

Econinvent (2014) Swiss Centre for life cycle inventories: Ecoinvent (V2.2). St-Gallen, Switzerland

Eriksson M, Strid I, Hansson P (2015) Carbon footprint of food waste management options in the waste hierarchy—a Swedish case study. J Clean Prod 93:115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.026

European Commission (2016) Paris agreement—European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/international/negotiations/paris/index_en.htm. Accessed 8 Mar 2016

Evangelisti S, Lettieri P, Borello D, Clift R (2014) Life cycle assessment of energy from waste via anaerobic digestion: a UK case study. Waste Manag 34:226–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2013.09.013

FAO (2013) Food Wastage Footprint. Italy, Rome

Finnveden G, Johansson J, Lind P, Moberg Å (2005) Life cycle assessment of energy from solid waste—part 1: general methodology and results. J Clean Prod 13:213–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.02.023

Finnveden G, Hauschild MZ, Ekvall T et al (2009) Recent developments in life cycle assessment. J Environ Manage 91:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.06.018

Frischknecht R, Althaus H, Bauer C et al (2007) The environmental relevance of capital goods in life cycle assessments of products and services. Int J LCA 2007:7–17

Fruergaard T, Astrup T (2011) Optimal utilization of waste-to-energy in an LCA perspective. Waste Manag 31:572–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.09.009

Grosso M, Nava C, Testori R et al (2012) The implementation of anaerobic digestion of food waste in a highly populated urban area: an LCA evaluation. Waste Manag Res 30:78–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242x12453611

Hall D, Turnbull R, Coleman T et al (2014) WRATE: user manual. Golder Associates Ltd, London

Heijungs R, Guinée JB (2007) Allocation and “what-if” scenarios in life cycle assessment of waste management systems. Waste Manag 27:997–1005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2007.02.013

Jeswani HK, Azapagic A (2016) Assessing the environmental sustainability of energy recovery from municipal solid waste in the UK. Waste Manag 50:346–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.02.010

Jeswani HK, Azapagic A, Schepelmann P, Ritthoff M (2010) Options for broadening and deepening the LCA approaches. J Clean Prod 18:120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.09.023

Khoo HH, Lim TZ, Tan RBH (2010) Food waste conversion options in Singapore: environmental impacts based on an LCA perspective. Sci Total Environ 408:1367–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.072

Kim M-H, Kim J-W (2010) Comparison through a LCA evaluation analysis of food waste disposal options from the perspective of global warming and resource recovery. Sci Total Environ 408(19):3998–4006

Kim M-HH, Song Y-EE, Song H-BB et al (2011) Evaluation of food waste disposal options by LCC analysis from the perspective of global warming: Jungnang case, South Korea. Waste Manag 31:2112–2120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.04.019

Laurent A, Christensen T, Bakas I (2014a) Review of LCA studies of solid waste management systems—part II: methodological guidance for a better practice. Waste Manag 34:589–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2013.12.004

Laurent A, Clavreul J, Bernstad A et al (2014b) Review of LCA studies of solid waste management systems—part I: lessons learned and perspectives. Waste Manag 34:573–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2013.10.045

Lebersorger S, Schneider F (2011) Discussion on the methodology for determining food waste in household waste composition studies. Waste Manag 31:1924–1933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.05.023

Lenzen M (2001) Errors in conventional and input–output—based life—cycle inventories. J Ind Ecol 4:127–148. https://doi.org/10.1162/10881980052541981

Miller RE, Blair PD (2009) Input-output analysis: foundations and extensions, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Morris J, Scott Matthews H, Morawski C (2013) Review and meta-analysis of 82 studies on end-of-life management methods for source separated organics. Waste Manag 33:545–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2012.08.004

Nixon JD, Wright DG, Dey PK et al (2013) A comparative assessment of waste incinerators in the UK. Waste Manag 33:2234–2244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2013.08.001

Parry A (2014) UK food waste—historical changes and how amounts might be influenced in the future. Banbury, UK

Quested T, Andrew P (2017) Household food waste in the UK, 2015. Banbury

Salas DA, Ramirez AD, Rodríguez CR et al (2016) Environmental impacts, life cycle assessment and potential improvement measures for cement production: a literature review. J Clean Prod 113:114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.078

Salemdeeb R, Al-tabbaa A, Reynolds C (2016) The UK waste input—output table: linking waste generation to the UK economy. Waste Manag Res 34:1089–1094. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242x16658545

Salemdeeb R, zu Ermgassen EKHJ, Kim MH et al (2017) Environmental and health impacts of using food waste as animal feed: a comparative analysis of food waste management options. J Clean Prod 140:871–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.049

Stamford L, Azapagic A (2014) Life cycle sustainability assessment of UK electricity scenarios to 2070. Energy Sustain Dev 23:194–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2014.09.008

Suh S, Lenzen M, Treloar GJ et al (2006) System boundary selection in life-cycle inventories using hybrid approaches. Environ Sci Technol 38:657–664

United Nations (2015) Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Paris

Wallace P (2011) Digestates: realising the fertiliser benefits for crops and grassland. Waste and Resources Action Programme, Banbury

Weidema BP, Wesnæs MS (1996) Data quality management for life cycle inventories—an example of using data quality indicators. J Clean Prod 4:167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-6526(96)00043-1

WRAP (2010) Chemical characterisation of foodwastes collected from welsh local. Waste and Resources Action Programme, Banbury

Zhang Y, Arnold R, Paavola T, Vaz F (2013) Compositional analysis of food waste entering the source segregation stream in four European regions and implications for valorisation via anaerobic digestion. In: Fourteenth international waste management and landfill symposium. CISA Publisher, Cagliari

Acknowledgements

The PhD research project of the RS is funded by the IDB Cambridge International Scholarship. CR is funded from the HEFCE Catalyst-funded N8 AgriFood Resilience Programme and matched funding from the N8 group of Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Salemdeeb, R., Bin Daina, M., Reynolds, C. et al. An environmental evaluation of food waste downstream management options: a hybrid LCA approach. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agricult 7, 217–229 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-018-0208-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-018-0208-8