Abstract

This article explores patterns and determinants of immigrant segregation for 10 immigrant groups in established, new, and minor destination areas. Using a group-specific typology of metropolitan destinations, this study finds that without controls for immigrant-group and metropolitan-level characteristics, immigrants in new destinations are more segregated and immigrants in minor destinations considerably more segregated than their counterparts in established destinations. Neither controls for immigrant-group acculturation or socioeconomic status nor those for demographic, housing, and economic features of metropolitan areas can fully account for the heightened levels of segregation observed in new and minor destinations. Overall, the results offer support for arguments that a diverse set of immigrant groups face challenges to residential incorporation in the new areas of settlement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2010, 13.6 % of Americans were foreign-born, and another 11.2 % had at least one parent who was born abroad.

The “group threat” literature almost exclusively focuses on the stock of ethnic/racial groups (e.g., Hood and Morris 1997; McDermott 2011; Oliver and Wong 2003; Quillian 1996; Rocha and Espino 2009; Taylor 1998) rather than recent changes in their populations posited here to influence perceptions and migration behavior (but see Hopkins 2010, 2011).

This analysis is not possible with recent American Community Survey data. Although dissimilarity scores for each of these groups can be estimated, most of the group-specific characteristics used in the analysis are unavailable. Table S2 in Online Resource 1 shows dissimilarity scores, by destination type, for the 10 groups from in 2005–2009, generally showing the same patterns as seen in 2000, although the levels are in some cases modestly different. I estimated models that regress 2000–2009 change in dissimilarity on 2000 group-level and metropolitan-level variables. These models yielded substantively similar results, showing that net of group and metropolitan characteristics, immigrant dissimilarity from native whites increased significantly more rapidly in new (b = 1.25, SE = .49) and minor (b = 2.35, SE = .50) destinations than in established areas.

In addition to including a relatively small (albeit growing) share of U.S. immigrants, smaller metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas have too few tracts to capture residential spatial patterns. Lichter et al. (2010) bypassed this issue by using block data, a level of geographic detail not possible here because of suppression of place-of-birth data at that more-refined level. Research has shown, however, that although levels of segregation tend to be higher at lower geographic levels, metropolitan estimates based on tracts, block groups, and blocks are highly correlated (Iceland and Steinmetz 2003).

These groups are not necessarily representative of all American immigrants, but they are a broad cross-section of the foreign-born population, constituting 56 % of all immigrants in 2000 and making up 77 % of all foreign-born growth between 1990 and 2000.

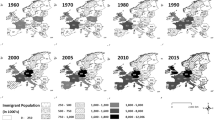

Data for 1980 to 2000 come from county-level summary files of decennial censuses. Because the 1970 summary tables do not include information on eight of the groups (all but Chinese and Mexican immigrants), the 1970 Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) was used to generate group populations in each of the top 100 metropolitan areas. This procedure presumably produces estimates more prone to sampling error; however, for Chinese and Mexican immigrants, the correlation between this PUMS–based approach and the summary-table approach is very high (r = .98), and both methods produce the same set of destination types.

In supplemental analysis, I tested several alternative destination-type operationalizations that either increased or decreased the stringency of being an established or new destination, including group-size restrictions and relaxing/increasing the extent to which population shares or growth exceed metropolitan averages. Although the size of the destination-type effects varies slightly depending on the approach used, the general interpretation is consistent and the magnitude of the coefficients shown here approximates the midpoint of all considered specifications.

Census 2000 does not tabulate income or housing tenure by country of birth. To circumvent this issue, I draw on metropolitan-level ethnic-group data (from Summary File 4). These data are imperfect because the subpopulations represent those identifying with specific ethnic groups on race, Hispanic origin, or (for Jamaicans and Haitians) ancestry questions, and thus include both the U.S.-born and foreign-born. What is essential is that these variables capture the variability in demographic, economic, and acculturation characteristics across immigrant groups and metropolitan areas. Correlation analyses suggest that they do: at the national level, the ethnic-origin data used here is strongly related to estimates specific only to immigrant-group members (white income parity, r = .99; homeowners, r = .98). Nevertheless, the percentage of each ethnic group that is foreign-born is included as an additional control.

Supplemental models explored the use of a destination typology based on the total immigrant population (i.e., “place-based”) rather than the group-based one employed here. When included alone or alongside the group-based typology, there were no significant differences between place-based established and non-established destinations, and this variable’s inclusion does not alter the statistical or substantive interpretation of the group-based destination-type coefficients. The interactions between the group-placed and place-based dummy variables do, however, indicate a somewhat heightened impact of being a new group in a non-established place, but these models also exhibit major signs of collinearity and instability, and are thus not shown. Complete results are available on request.

In additional analyses, I considered occupational concentration in four other sectors of labor markets: health, sales, construction, and government. The coefficients on each of these in the full model were small and nonsignificant.

Although these measures can take values anywhere between 0 and 100, their truncated range makes a linear model technically inappropriate. However, residual plots reveals no major violations of regression assumptions due to truncation, and skewness/kurtosis statistics suggest that the D values approximate a normal distribution (s = 0.31, k = 2.78).

Fixed-effects models that account for metropolitan characteristics that do not vary across groups produce results that are substantively similar to those presented here. The coefficients for new destinations (b = 2.44; SE = 0.93) and minor destinations (b = 4.77; SE = 0.95) under the fixed-effects approach are nearly identical to those shown in Table 3.

The substantive interpretation of the unweighted and weighted models is similar. In the full regression model with weights, the new destination coefficient is smaller than that in the unweighted models but remains positive and significant (b = 1.57; SE = 0.78); the coefficient for minor destinations is larger in the weighted results (b = 5.87; SE = 0.97) than the unweighted ones.

One possible explanation for the higher levels of segregation in minor destinations is increased sampling error associated with the calculation of D for small groups. However, even when metropolitan areas with fewer than 5,000 group members are excluded, segregation in minor destinations remains higher than in established and new destinations.

Modifying recent arrivals to include immigrants who entered the country between 1990 and 1994 does not change the interpretation of the results (arrived 1990–2000, Model 2: b = 0.14, SE = 0.05; Model 3: b = 0.09, SE = 0.04).

Substituting a measure of a group’s family does not alter the interpretation of the results (family income, in $1,000s, Model 2: b = 0.04, SE = 0.06; Model 3: b = 0.02, SE = 0.04).

The suppression of the new destinations coefficient between Models 2 and 3 is due mostly to the positive effect of metropolitan population size on segregation. The zero-order correlation between the two variables is r = –.21.

When entered separately, both coefficients are significantly negative (percentage immigrant b = –0.21; SE = .04; top 5 gateway b = –1.69; SE = 1.29). Importantly, their inclusion does not alter the results of the group-specific destination-types in any meaningful way. With both excluded from the analysis, segregation in new (b = 2.53; SE = 1.05) and minor (b = 5.21; SE = 1.01) destinations remains significantly higher than in established areas.

Setting Mexicans as the referent in these models indicates that their adjusted level of segregation from native whites is significantly lower than all groups except Koreans (b = 3.12; SE = 2.82) and Chinese (b = 4.67; SE = 2.64).

Results generated partially from a forward-stepwise approach lead to similar conclusions.

Differences in the effect of income parity are statistically significant (at p < .05) between Mexican immigrants and all others but Vietnamese immigrants, and between Vietnamese and both Korean and Indian immigrants.

Differences in the effects of destination type (both new and minor destinations) are significant only between Chinese immigrants and all other groups.

In supplemental analyses, I explored models that pool Jamaicans and Haitians and estimate the reduced set of variables in Table 4 on dissimilarity from native whites. The results show that these groups are no more nor less segregated from native whites in new destinations (b = .82, SE = 3.12) yet more segregated in minor areas, although not significantly (b = 1.78, SE = 2.63), than in established areas. However, the small N of 53, even when these groups are pooled, may contribute to model instability; thus, I do not present these estimates.

Supplemental models for Koreans reveal the importance of metropolitan black and retirement populations, both of which significantly increase segregation.

References

Alba, R., Denton, N., Hernandez, D., Drisha, I., McKenzie, B., & Napierala, J. (2010). Nowhere near the same: The neighborhoods of Latino children. In N. Landale, S. McHale, & A. Booth (Eds.), Growing up Hispanic: Health and development of children of immigrants (pp. 3–48). Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Bartel, A. P. (1989). Where do U.S. immigrants live? Journal of Labor Economics, 7, 371–391.

Capps, R., Rosenblum, M. R., Rodriguez, C., & Chisti, M. (2011). Delegation and divergence: A study of 287(g) state and local immigration enforcement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Charles, C. Z. (2000). Neighborhood racial-composition preferences: Evidence from a multi-ethnic metropolis. Social Problems, 47, 379–407.

Charles, C. Z. (2003). The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 167–207.

Charles, C. Z. (2006). Won’t you be my neighbor? Race, class, and residence in Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cortina, R., & Gendreau, M. (Eds.). (2003). Immigrants and schooling: Mexicans in New York. New York: Center for Migration Studies.

Crowder, K., Hall, M., & Tolnay, S. (2011). Neighborhood immigration and native out-mobility. American Sociological Review, 76, 25–47.

Cutler, D., Glaeser, E. L., & Vigdor, J. (2008). Is the melting pot still hot? Explaining resurgence of immigrant segregation. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 478–497.

Ellen, I. G. (2000). Sharing America’s neighborhoods: The prospects for stable, racial integration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ellis, M., & Goodwin-White, J. (2006). 1.5 generation internal migration in the U.S.: Dispersion from states of immigration? International Migration Review, 40, 899–926.

Esbenshade, J. (2007). Division and dislocation: Regulating immigration through local housing ordinances (Immigration Policy Center Special Report). Washington, DC: American Immigration Law Foundation.

Espiritu, Y. L. (1993). Asian American panethnicity: Bridging institutions and identities. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Fang, D., & Brown, D. (1999). Geographic mobility of the foreign-born Chinese in large metropolises, 1985–1990. International Migration Review, 33, 137–155.

Farley, R., & Frey, W. H. (1994). Changes in the segregation of whites from blacks during the 1980s: Small steps toward a more integrated society. American Sociological Review, 59, 23–45.

Farley, R., Fielding, E. L., & Krysan, M. (1997). The residential preferences of blacks and whites: A four-metropolis analysis. Housing Policy Debate, 8, 763–800.

Fennelly, K. (2008). Prejudice toward immigrants in the Midwest. In D. Massey (Ed.), New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration (pp. 115–178). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Fischer, M. J., & Tienda, M. (2006). Redrawing spatial color lines: Hispanic metropolitan dispersal, segregation, and economic opportunity. In M. Tienda & F. Mitchell (Eds.), Hispanic and the future of America (pp. 100–138). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Frey, W. H., & Liaw, K.-L. (2005). Migration within the United States: Role of race-ethnicity. Brookings-Wharton Papers of Urban Affairs, 2005, 207–262.

Gurak, D. T., & Kritz, M. M. (2000). The interstate migration of U.S. immigrants: Individual and contextual determinants. Social Forces, 78, 1017–1033.

Hall, M., Crowder, K. D., & Tolnay, S. (2010, April). Immigration and native residential mobility in established, new, and nongateway metropolitan destinations. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Dallas, TX.

Hardwick, S. W., & Meacham, J. E. (2008). “Placing” the refugee diaspora in Portland, Oregon: Suburban expansion and densification in a re-emerging gateway. In A. Singer, S. Hardwick, & C. Brettell (Eds.), Twenty-first century gateways: Immigrant incorporation in suburban America (pp. 225–256). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Hood, M. V., & Morris, I. L. (1997). ¿Amigo o enemigo? Context, attitudes, and Anglo public opinion toward immigration. Social Science Quarterly, 78, 309–323.

Hopkins, D. J. (2010). Politicized places: Explaining where and when immigrants provoke local opposition. American Political Science Review, 104, 40–60.

Hopkins, D. J. (2011). National debates, local responses: The origins of local concern about immigration in the U.K. and the U.S. British Journal of Political Science, 41, 499–524.

Iceland, J. (2009). Where we live now: Immigration and race in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Iceland, J., & Nelson, K. A. (2008). Hispanic segregation in metropolitan America: Exploring the multiple forms of spatial assimilation. American Sociological Review, 73, 741–765.

Iceland, J., & Scopilliti, M. (2008). Immigrant residential segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas, 1990–2000. Demography, 45, 79–94.

Iceland, J., & Steinmetz, E. (2003). The effects of using census block groups instead of census tracts when examining residential housing patterns (Working paper). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Itzigsohn, J. (2004). The formation of Latino and Latina panethnic identities. In N. Foner & G. M. Fredrickson (Eds.), Not just black and white: Historical and contemporary perspectives on immigration, race, and ethnicity in the United States (pp. 197–216). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Jargowsky, P. (1997). Poverty and place: Ghettos, barrios, and the American city. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Jones-Correa, M. (1998). Between two nations: The political predicament of Latinos in New York City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Kandel, W., & Cromartie, J. (2004). New patterns of Hispanic settlement in rural America. (Rural Development Research Report 99). Washington, DC: Economic Research Service, USDA.

Kibria, N. (1998). The contest meanings of “Asian American”: Racial dilemmas in the contemporary US. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 21, 939–958.

Kim, A. H., & White, M. J. (2010). Panethnicity, ethnic diversity, and residential segregation. The American Journal of Sociology, 115, 1558–1596.

Kim, K. C., & Kim, S. (2001). The ethnic roles of Korean immigrant churches in the United States. In H.-Y. Kwan, K. C. Kim, & R. S. Warner (Eds.), Korean Americans and their religions: Pilgrims and missionaries from a different shore (pp. 71–94). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Kritz, M. M., & Nogle, J. M. (1994). Nativity concentration and internal migration among the foreign-born. Demography, 31, 509–524.

Krysan, M. (2002). Whites who say they’d flee: Who are they, and why would they leave? Demography, 39, 675–696.

Kuk, K., & Lichter, D. T. (2011, April). New Asian destinations: A comparative study of traditional gateways and emerging immigrant destinations. Paper presented at the Population Association of America, Washington, DC.

Leach, M. A., & Bean, F. D. (2008). The structure and dynamics of Mexican migration to new destinations in the United States. In D. S. Massey (Ed.), New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration (pp. 51–74). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Levitt, P. (2007). Dominican Republic. In M. C. Waters & R. Ueda (Eds.), The new Americans: A guide to immigration since 1965 (pp. 399–411). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ley, D. (2007). Countervailing immigration and domestic migration in gateway cities: Australian and Canadian variations on an American theme. Economic Geography, 83, 231–254.

Li, W. (Ed.). (2006). From urban enclave to ethnic suburb: New Asian communities in Pacific Rim countries. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Li, W. (2009). Ethnoburb: The new ethnic community in urban America. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Lichter, D. T., & Johnson, K. (2006). Emerging rural settlement patterns and the geographic redistribution of America’s new immigrants. Rural Sociology, 70, 109–131.

Lichter, D. T., & Johnson, K. (2009). Immigrant gateways and Hispanic migration to new destinations. International Migration Review, 43, 496–518.

Lichter, D. T., Parisi, D., Taquino, M. C., & Grice, S. M. (2010). Residential segregation in new Hispanic destinations: Cities, suburbs, and rural communities compared. Social Science Research, 39, 215–230.

Logan, J. R., Stults, B., & Farley, R. (2004). Segregation of minorities in the metropolis: Two decades of change. Demography, 41, 1–22.

Massey, D. S. (1985). Ethnic residential segregation: A theoretical synthesis and empirical review. Sociology and Social Research, 69, 315–350.

Massey, D. S. (Ed.). (2008). New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1989). Hypersegregation in U.S. metropolitan areas: Black and Hispanic segregation along five dimensions. Demography, 26, 373–393.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Masuoka, N. (2006). Together they become one: Examining the predictors of panethnic group consciousness among Asian Americans and Latinos. Social Science Quarterly, 87, 993–1011.

McConnell, E. D. (2008). The U.S. destinations of contemporary Mexican immigrants. International Migration Review, 42, 767–802.

McDermott, M. (2011). Racial attitudes in city, neighborhoods, and situational contexts. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 634, 153–173.

Min, P. G. (1992). The structure and social functions of Korean immigrant churches in the United States. International Migration Review, 26, 1370–1394.

Nogle, J. M. (1997). Internal migration patterns for the U.S. foreign born. International Journal of Population Geography, 3, 1–13.

Okamoto, D. G. (2003). Toward a theory of panethnicity: Explaining Asian American collective action. American Sociological Review, 68, 811–842.

Oliver, J. E., & Wong, J. (2003). Intergroup prejudice in multiethnic settings. American Journal of Political Science, 47, 567–582.

Pais, J., South, S. J., & Crowder, K. (2009). White flight revisited: A multiethnic perspective on neighborhood out-migration. Population Research and Policy Review, 8, 321–346.

Park, J., & Iceland, J. (2011). Residential segregation in metropolitan established immigrant gateways and new destinations, 1990–2000. Social Science Research, 40, 811–821.

Price, M., Cheung, I., Friedman, S., & Singer, A. (2005). The world settles in: Washington, DC, as an immigrant gateway. Urban Geography, 26, 61–83.

Quillian, L. (1996). Group threat and regional change in attitudes toward African-Americans. The American Journal of Sociology, 102, 816–861.

Ramakrishnan, K. S., & Lewis, P. (2005). Immigrants and local governance: The view from city hall. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.

Reis, M. (2004). Theorizing diaspora: Perspectives on “classical” and “contemporary” diaspora. International Migration, 42, 41–60.

Rocha, R. R., & Espino, R. (2009). Racial threat, residential segregation, and the policy attitudes of Anglos. Political Research Quarterly, 62, 415–426.

Rosenbaum, E., & Friedman, S. (2007). The housing divide: How generations of immigrants fare in New York’s housing market. New York: New York University Press.

Ross, S., & Yinger, J. (2002). The color of credit: Mortgage discrimination, research methodology, and fair-lending enforcement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Singer, A. (2005). The rise of new immigrant gateways: Historical flows, recent settlement trends. In A. Berube, B. Katz, & R. E. Lang (Eds.), Redefining urban and suburban America: Evidence from Census 2000 (Vol. II, pp. 41–86). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Singer, A. (2009). The new geography of United States immigration. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Skop, E. (2012). The immigration and settlement of Asian Indians in Phoenix, Arizona 1965–2011: Ethnic pride vs. racial discrimination. New York: Edwin Mellen.

Smith, R. C. (1996). Mexicans in New York City: Membership and incorporation of new immigrant group. In G. Haslip-Viera & S. L. Baver (Eds.), Latinos in New York: Communities in transition (pp. 57–103). South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Smith, R. C. (2001). Mexicans: Social, educational, economic, and political problems and prospects in New York. In N. Foner (Ed.), New immigrants in New York (pp. 275–300). New York: Columbia University Press.

Suro, R., & Singer, A. (2003). Changing patterns of Latino growth in metropolitan America. In B. Katz & R. E. Lang (Eds.), Redefining urban and suburban America (Vol. 1, pp. 181–210). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Taylor, M. (1998). How white attitudes vary with the racial composition of local populations: Numbers count. American Sociological Review, 63, 512–535.

Teaford, J. C. (2007). The American suburb: The basics. New York: Routledge.

Timberlake, J. M., & Iceland, J. (2007). Change in racial and ethnic residential inequality in American cities, 1970–2000. City and Community, 6, 335–365.

Waters, M. C., & Ueda, R. (Eds.). (2007). The new Americans: A guide to immigration since 1965. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wen, M., Lauderdale, D. S., & Kandula, N. R. (2009). Ethnic neighborhoods in multiethnic America, 1990–2000: Resurgent ethnicity in the ethnoburbs? Social Forces, 88, 425–460.

White, M. J. (1987). American neighborhoods and residential differentiation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

White, M. J., & Glick, J. (2009). Achieving anew: How new immigrants do in American schools, jobs, and neighborhoods. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Wright, R., & Ellis, M. (2000). Race, region, and territorial politics of immigrants in the U.S. International Journal of Population Geography, 6, 197–211.

Yanow, D. (2003). Constructing race and ethnicity in America: Category-making in public policy and administration. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Zelinsky, W., & Lee, B. A. (1998). Heterolocalism: An alternative model of the sociospatial behavior of immigrant ethnic communities. International Journal of Population Geography, 4, 281–298.

Zhou, M. (1992). Chinatown: The socioeconomic potential of an urban enclave. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Zúñiga, V., & Hernández-León, R. (Eds.). (2005). New destinations: Mexican immigration in the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Acknowledgments

This article acknowledges support from the Penn State University Alumni Association and the Population Research Institute at Penn State, which receives core funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant R24-HD041025). I am thankful to Editor Tolnay and three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments, as well as to Gordon De Jong, Glenn Firebaugh, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Deb Graefe, John Iceland, Barry Lee, and Audrey Singer for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 1015 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, M. Residential Integration on the New Frontier: Immigrant Segregation in Established and New Destinations. Demography 50, 1873–1896 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0177-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0177-x