Abstract

Experiments were conducted in laboratory bioreactors and in field plots to test effects of certain cultivated members of the grass family (Poaceae = Gramineae), including wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. Yolo), barley (Hordeum vulgare cv. UC337), oats (Avena sativa cv. Montezuma), triticale (X Triticosecale), and a sorghum-sudangrass hybrid (Sorghum bicolor x S. sudanense = “sudex”, cv. Green Grazer V) for soil disinfestation potential. Soilborne pest organisms tested for effects on survival and activity included the phytopathogens Sclerotium rolfsii, Pythium ultimum and Meloidogyne incognita, and a variety of weed taxa. Following soil amendment, bioreactors were incubated for 7 days at ambient (23°C) or elevated, but sublethal (38°C day/27°C night), soil heating regimens. Addition of each of the poaceous amendments to soil at 23°C resulted in inconsistently reduced tomato root galling (49–97%) by M. incognita, or reduced recovery of S. rolfsii and P. ultimum (0–100%) fungi in soil, after 7 days’ incubation (P ≤ 0.05). When the organisms were exposed to the poaceous soil amendments at the 38o/27o temperature regimen, nematode galling and recovery of active fungi were consistently and significantly reduced by 98–100%. These results demonstrated feasibility of soil disinfestation (“biofumigation”) by activity of poaceous amendments, further aided by combining plant residues with soil heating (e.g. solarization). Results from three field experiments with sudex cover crops, conducted throughout the growing season, demonstrated biocidal activity on a range of weedy plants, including Amaranthus retroflexus, Calandrinia ciliata, Cerastium arvense, Digitaria sanguinalis, Echinochloa crus-galli and Poa annua. Both shoots and roots of sudex provided allelopathic weed biomass reductions of 35–100%, and for at least 106 days after shredding. Deleterious activity of shredded residues incorporated in soil was less persistent. These properties in poaceous crops can be useful for soil disinfestation; however, harmful phytotoxicity to subsequent crops may also result. In order to take full advantage of these low-input measures for controlling soilborne diseases and pests, further understanding of their properties must be gained, and user guidelines developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increased rotational production of many agronomic grass and cereal grain (plant family Poaceae = Gramineae) crops seems destined to be part of the agricultural future. This may occur, not only to produce more food for ever-increasing numbers of people and livestock on the planet, but also to provide feedstocks for lignocellulosic biofuels made from plant residues, such as from straw remaining after harvest (Gomez et al. 2008; Jenkins et al. 2009). These crops may include the small grain staples widely grown for human consumption, e.g., wheat, rice, barley, etc., as well as those grown primarily for vegetative biomass and livestock feed, such as sugarcane, sudangrass and sorghum. Increased sequencing into grass family crops may occur even in agricultural regions, such as in the Mediterranean climatic zones, where intensive relay planting of high-value horticultural crops is commonly practiced. Due to rising costs, increased scarcity of water and other resources, and the vital importance of maintaining long-term, sustainable agricultural production systems, improving cropping efficiency through value-added, or “multi-tasking” uses for all portions of crops is becoming increasingly necessary (Stapleton and Bañuelos 2009). At the same time, care must be taken so as to not remove excessive amounts of plant biomass from the land, so that soil quality and fertility suffer. The development of pest management tactics based on use of non-harvested crop components can be an important facet of overall agricultural sustainability.

It is widely known, but often not considered, that many poaceous plants possess properties that are inhibitory to other life forms (Creamer et al. 1996; Doohan et al. 2000; Widmer and Abawi 2000). The bioactivity of poaceous plants may be based on allelopathy (Ben-Hammouda et al. 1995; Del Moral 1975) and/or toxicity of their decomposition products in soil (Davis et al. 1996; Dover et al. 2004; Guenzi et al. 1967; Patrick et al. 1963). Allelopathy depends, to a great extent, on organisms producing secondary metabolites — chemical compounds not necessarily needed for their basic metabolism, but which often confer ecological advantages by killing, weakening or repelling nearby competitors for nutrients, space or other niche resources (Weston 2005). For example, many of the synthesized antibiotics used in human and animal medicine were originally discovered as secondary metabolites of various microorganisms. Although potentially useful levels of pesticidal activity have been demonstrated from certain poaceous plants and from their decomposing residues, the broad range of these toxic properties also has resulted in undesirable instances of phytotoxicity to subsequent crops (Guenzi et al. 1967; Summers et al. 2009; Waddington 1978; Weston et al. 1989).

The potential of biomass crops, primarily those in the cabbage family (Brassicaceae), for use in soil biofumigation and soil/water bioremediation was recently discussed (Stapleton and Bañuelos 2009). In previous experimentation with residues of brassicaceous (Gamliel and Stapleton 1993; Stapleton and Duncan 1998) and alliaceous (Mallek et al. 2007) crop plants as soil amendments, biocidal activity was shown to increase with increasing soil temperature. We also reported that cover cropping with a sorghum–sudangrass hybrid [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench x Sorghum sudanense (P.) Stapf. = “sudex”] was detrimental to subsequent tomato, lettuce and broccoli transplants because of allelopathic phytotoxicity (Summers et al. 2009). Indeed, various Sorghum spp., such as sudex, grain sorghum, sudangrass and johnsongrass (S. halepense L.), have been shown to inhibit emergence or development of a broad range of annual and perennial crop species (Forney and Foy 1985; Geneve and Weston 1988; Iyer 1980). However, in addition to their sometimes negative impact on subsequently planted crops, the contributions of various poaceous species and cultivars on populations of weeds also must be considered (Burgos and Talbert 1996). For example, significant reductions in weed populations have been reported in wheat following sorghum (Cheema and Khaliq 2000), and root exudates of S. bicolor reduced growth of velvet leaf (Abutilon theophrasti), thorn apple (Datura stramonium), redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), yellow foxtail (Setaria viridis) and barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli) (Einhellig and Souza 1992). These findings point to possible pest management utility of crop rotations with agronomic grasses.

In this study, our objectives were to conduct experiments with containerized soil, at laboratory scale, to test the pest management effects of amendment with residues of small grain crops. The experiments, conducted at two temperature regimens, evaluated survival and activity of the nematode plant pathogen Meloidogyne incognita, and the fungal pathogens Sclerotium rolfsii and Pythium ultimum, following exposure to cultivated wheat, barley, oat and triticale residues in soil. Furthermore, we conducted field experiments to test effects of sudex cover crop plants, previously shown to be deleterious to vegetable crop transplants (Summers et al. 2009), for weed control.

Materials and methods

Laboratory bioreactor experiments—effects of small grain residues on nematode and fungal phytopathogens

As described in a preliminary report (Stapleton 2006), Hanford fine sandy loam soil (Typic Xerorthents – 46% sand, 45% silt, 9% clay; pH 7.4) naturally infested with M. incognita [ca 150 second-stage juveniles (J2) per liter of soil] and P. ultimum [ca 29 propagules (oospores) per gram of soil] was used. Laboratory-grown sclerotia of S. rolfsii were added to the soils in mesh bags (30 sclerotia per bag) prior to treatment. Soil for treatment was loaded into bioreactors, consisting of wide-mouthed, 2-liter-capacity glass jars, with openings covered by clear, 0.031 mm (1.25 mil), low-density polyethylene film, tightly secured with rubber bands. This technique allowed for limited gas exchange between bioreactors and ambient air, and simulated conditions in field soil during solarization or bed mulching. Four replicate bioreactors were then incubated in a modified Wisconsin-type water bath with diurnal temperature maximum and minimum of 38°C and 27°C, respectively, while four others were simultaneously maintained in a similar water bath set at a constant 23°C (± 1°C). The elevated temperature water bath was set to deliver 8 h heating per day, which gave samples in bioreactors ca 6 h at maximum temperature during each 24-h period. The small grain crop amendments used in these tests were air-dried and milled straw residues of mature wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. Yolo), barley (Hordeum vulgare cv. UC 337), oats (Avena sativa cv. Montezuma) and triticale (x Triticosecale) plants which were collected from recently harvested fields in the Fresno, California area. All amendments were uniformly incorporated into soil at a concentration of 1.9% (weight/weight – dry basis), the approximate quantity of stubble residues which would be incorporated into the plow layer of field soil at the end of a cropping cycle in commercial production. Effects of treatments on M. incognita were estimated after 7 days’ incubation using a bioassay procedure, in which treated soil was aired in open plastic bags for 24 h following incubation in bioreactors, then placed in two 10-cm-diam pots per replication. A single plant of a susceptible tomato cultivar (Lycopersicon esculentum cv. Cherry Belle) was transplanted into each pot and the pots were maintained in a glasshouse at 30°C maximum and 21°C minimum. After 6 weeks’ growth, root systems were excised, washed and an arbitrary gall rating was made by visual examination (0–4 scale, where 0 = no galls evident and 4 = 76–100% of roots galled) (Stapleton and Duncan 1998). Sensitivity of S. rolfsii to treatments was determined by retrieving and surface-disinfesting the 30 sclerotia from each container, then incubating them on potato dextrose agar plates to determine germinability. Effects on P. ultimum were determined by sampling soil from containers, then air-drying and spreading aliquots on a selective agar medium, as described previously (Gamliel and Stapleton 1993). Fungal colonies were identified and enumerated after incubation.

Field experiments—effects of sorghum/sudangrass (sudex) cover crops on weeds

Three field studies were conducted at the University of California, Kearney Research and Extension Center, ca 12.5 km southeast of Fresno, California (36˚36’ north; 119˚30’ west; elevation 102 m). The soil type was Hanford fine sandy loam (Typic Xerorthents), and experiments were done in conjunction with vegetable crop transplant experiments, according to methodology described previously (Summers et al. 2009). In Experiment 1 (1999), raised planting beds, 102 cm between centers, were formed and pre-planting fertilizer (15-15-15% of N-P-K) was incorporated to a depth of 15 cm. Six rows of sudex (cv. Green Grazer V) were planted on each bed on 6 August, at the rate of 13.6 kg ha−1. Two drip irrigation lines were placed on the surface of each planting bed and water was applied to field capacity. Following seedling stand establishment, liquid fertilizer (17-0-0% of N-P-K) was added through the drip system. The green sudex plants were shredded when they reached a height of ca 1.4 m on 24 September, using a tractor-drawn mower. Plots were sprayed 10 days later with a 2% (volume/volume) solution of glyphosate, using a CO2-powered backpack sprayer, to preclude plant regrowth. The shredded sudex plants formed a dense mulch layer over the surface of the planting beds. Four replications were prepared for each of the following treatments: (i) plants shredded and sprayed with glyphosate, then left on the soil surface; (ii) plants shredded, sprayed, then incorporated in soil with a rototiller; and (iii) fallow control (not planted, but sprayed). Each plot was 1 m long. All plots were regularly drip irrigated and fertilized (17-0-0% of N-P-K) every 2 weeks. Vegetable plants were transplanted into the beds as described by Summers et al. (2009). Following the vegetable crop harvests, all weeds from a 0.093 m2 area were harvested on 29 November, dried and weighed.

Methodology for Experiments 2 and 3 (2000) was similar to that of Experiment 1, but used 152-cm-wide planting beds. Sudex seed was planted on 1 May (Experiment 2 — spring planting) and 26 July (Experiment 3 — summer planting). The plants from Experiment 2 were shredded as before, on 27 June, when green plants were ca 1.8 m tall; and those from Experiment 3 were shredded on 5 September, when plants were ca 2 m tall. Plant stubble regrowth was sprayed 10 days later with 2% glyphosate herbicide, as described above. Plots in both Experiments 2 and 3 were arranged in randomized complete block design, with six replications each of the following treatments: (i) plants shredded, sprayed with glyphosate, and shoot residues left on the soil surface; (ii) shredded plants raked off and placed on a fallow (no glyphosate) bed that had not previously been seeded with sudex (referred to as “shoots only”; (iii) plants shredded, sprayed, then shredded stems manually removed from plots, leaving only the roots plus 3–5 cm of surface stubble (referred to as “roots only”); (iv) plants shredded, sprayed, then shoots and roots incorporated into soil (referred to as “incorporated”) with a tractor-mounted rototiller, 14 days after shredding; and (v) fallow control (no plants, residues, or glyphosate spray). Each plot was 4.5 m long by 1.5 m wide. Prior to planting, two drip tape lines were placed on the surface of each planting bed. Irrigation water and liquid fertilizer were applied weekly through the drip system as before.

Forty-three days after sudex shredding (8 August), the total weed biomass in Experiment 2 was determined, following tomato harvest, by removing the weeds from 1 m2 of soil surface, selected at random in each plot. Weeds were placed in paper bags, dried for 5 days at 70°C and then weighed. These procedures were repeated 50 days (15 August) and 57 days (22 August) after sudex shredding.

Similarly, the weed biomass from Experiment 3 was collected on 25 October and 20 December for the first planting, and on 21 December for the second planting, then dried and weighed as before.

Data analysis

For the laboratory bioreactor study, experiments were conducted in a factorial arrangement, with soil [amendment] and [temperature] as the main effects. At least two experiments were conducted for each amendment and soil temperature combination. Sclerotial germination (S. rolfsii) and nematode gall rating data were expressed in percent of the nonamended, nonheated control. All raw or arcsine-transformed data from laboratory experiments and field trials were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the plot designs used; and treatment means, where appropriate, were separated using Fisher’s Protected LSD test.

Results

Laboratory bioreactor experiments—nematode and fungal phytopathogens

Analysis of variance for the nonamended, 23°C temperature (control) treatment showed that the individual experiments were not significantly different for galling of tomato roots by M. incognita, or for germination of S. rolfsii sclerotia. Experiments were, however, significantly different for P. ultimum survival; therefore survival of P. ultimum after exposure to treatments was calculated relative to the corresponding nonamended control, at the lower heating regimen, for each experiment. Post-treatment population assays of each of the three test phytopathogens showed that the higher, 38o/27°C soil temperature regimen used during the experiments was sublethal to propagules not exposed to amendments, with no significant difference between higher and lower temperature regimens in nonamended soil (Tables 1, 2 and 3). For each of the test phytopathogens, however, the main effects of soil [amendment] and [temperature] were significant. The [amendment x temperature] interaction was significant for S. rolfsii (P ≤ 0.01) and P. ultimum (P ≤ 0.05), but not for root galling caused by M. incognita.

Addition of the wheat and barley residues to moist soil maintained at 23°C significantly reduced root galling of tomato due to M. incognita by 97% and 56%, respectively, when compared with the nonheated control after 7 days’ exposure. On the other hand, the oat and triticale residues did not significantly affect root galling. However, root galling markedly and consistently diminished following bioreactor incubation at the higher temperature regimen of 38o/27°C, and all four of the poaceous soil amendments significantly reduced gall ratings by 97–100% (Table 1). Although data were not collected, stunting was observed on some of the tomato transplants during the bioassays in amended soil.

The dried and milled wheat, barley and oat stem amendments, when added to soil maintained at 23°C, all caused significant germination reductions of S. rolfsii sclerotia by 31–100% after 7 days’ incubation. Due to logistical constraints, triticale residues were not included in the tests with S. rolfsii. As with most of the experimental assays comprising this study, the wheat stem amendment caused the most deleterious effect on sclerotial germination, when incubated at 23o C. At the higher—but sublethal—temperature regimen, sclerotial germination was completely inhibited following exposure to each amendment tested (Table 2).

Soil amendment with wheat, barley and oats, but not triticale, resulted in reduced recovery numbers of P. ultimum propagules, by 85–96%, after 7 days’ incubation at 23°C. When bioreactors containing amended soil were exposed to the higher, 38o/27°C soil temperature regimen, the wheat, barley and oat residues reduced P. ultimum recovery by 97–100%, and the triticale amendment now gave a lesser, but significant recovery reduction of 73% (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 3).

Field experiments—effects of sorghum/sudangrass (sudex) residues on weeds

In Experiment 1, plots containing sudex shoot and root residue surface mulch remained 100% weed-free throughout the 55-day post-shredding observational period in autumn. However, there was a significantly lower inhibition level of 35% (P ≤ 0.05), based on oven-dry weed biomass weights, in plots in which the sudex had been soil-incorporated, as compared with the control (Table 4). Weeds in both the soil-incorporated and control plots had formed a dense mat over the soil surface by the time samples were taken. Although the weeds were not separated to species following collection, we visually estimated that annual blue grass (Poa annua) comprised ca 90% of the biomass harvested. Most of the remaining weed biomass consisted of red maids (Calandrinia ciliata) and field chickweed (Cerastium arvense).

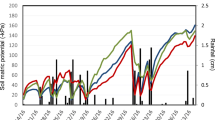

In Experiment 2, all sudex treatments initially demonstrated significant, weed-inhibiting properties, as compared with the control. At the first weed sampling, 43 days after sudex shredding, biomass of warm-season annual weeds was reduced by 68-85% (Fig. 1). By 57 days after sudex shredding, weed growth in the soil-incorporated plots was no different from that in the control plots. However, the other sudex treatments maintained levels of 74–94% weed inhibition (P < 0.05), as compared with the control. Although the weeds were not separated by species, barnyardgrass (E. crus-galli) visually appeared to predominate, followed by crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis) and redroot pigweed (A. retroflexus).

Oven-dry weed biomass (grams per square meter) from plots amended with various plant portions of a sorghum–sudangrass hybrid [Sorghum bicolor x S. sudanense (“sudex”) cv. Green Grazer V], at days post-shredding of the cover crop. Overlapping error bars indicate values that are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Fisher’s Protected LSD test

Results from Experiment 3 were similar to those from the previous two. In the first planting (26 September), in plots assessed 50 days after sudex shredding, weed biomass was reduced by 89–100% over weed density in the control plot regardless of sudex treatment (Table 5). At 106 days (15.1 weeks) after shredding, weed biomass in first-planting plots containing surface shoots (shoots plus roots, and shoots only) was only 1–5% of that found in the control plots, whereas weeds in the root (plus associated stubble) and soil-incorporated plots showed partial and complete regrowth, respectively. In the second planting, following broccoli and lettuce harvest, weed biomass assessed at 106 days after shredding was still at least 42% lower (P < 0.05) in all sudex amendment treatments than in the control plots (Table 5), and the shoots plus roots, and shoots only treatments maintained weed biomass reductions of >99%. Nearly the entire weed population in this experiment consisted of annual bluegrass (P. annua) plants.

Discussion

The laboratory bioreactor experiments conducted in this study showed that amendment of phytopathogen-infested field soil, with certain poaceous crop residues at a constant temperature of 23°C, provided mostly significant levels of deleterious activity against M. incognita, P. ultimum and S. rolfsii. Of the amendments tested at 23°C, ‘Yolo’ wheat provided the most consistent activity against M. incognita and S. rolfsii, and triticale the least. When incubated at the higher temperature regimen of 38o/27°C (day/night), all amendments demonstrated consistently increased deleterious activity that was statistically indistinguishable, except that triticale residues had the least biocidal activity against P. ultimum.

As with most bioactive chemicals, including synthetic pesticides (Stapleton 2000) and brassicaceous and alliaceous plant residues (Gamliel and Stapleton 1993; Mallek et al. 2007; Stapleton and Duncan 1998), deleterious activity of the tested poaceous amendments increased with increasing soil temperature. These very consistent results across the various plant taxa tested indicate that, as expected, the volatility and concentration of bioactive chemicals released during plant residue decomposition in soil increases with increasing temperature (Gamliel and Stapleton 1993; Stapleton and Bañuelos 2009). Also, given the statistically significant interactions of the [amendment] and [temperature] factorial effects tested with S. rolfsii and P. ultimum (but not with M. incognita), the targeted phytopathogens were shown to incur more harm from simultaneous application of the dissimilar stress sources, i.e., chemical and temperature, than from either stress source alone. These results confirmed the utility of combining plant residue soil amendments with soil heating techniques (e.g. solarization) for improved soil disinfestation.

It is commonly assumed that in vitro, bench-top experiments, such as those conducted in bioreactors in this study, often give more dramatic results than those obtained under similar conditions in a natural environment. Therefore, the field experiments conducted with the sorghum-sudangrass (sudex) cover crop plants and residues provided strong support for our laboratory study. Over the course of three experiments conducted at different times during the year, the sudex plant residues, particularly the shoot portions, clearly gave a dramatic and long-lasting reduction of both summer and winter annual weed species, regardless of seasonal climate. The deleterious effects were apparent on both broadleaved weeds and grasses, and were similar to those on vegetable transplants grown in the same plots (Summers et al. 2009).

The consistent and significant inhibition of targeted organisms by certain cultivated grasses demonstrated in these experiments is not surprising, given many previous reports of lethal or inhibitory effects against various plant pests (see e.g. Miller 1996; Snapp et al. 2007; Wardle et al. 1996). A portion of the below-ground, inhibitory activity of grass family members results from production of toxic, decomposition compounds (see e.g. Lynch 1977; Putnam and DeFrank 1983). However, the effects of allelochemicals in growing plants can be potent and long-lasting (Ben-Hammouda et al. 1995; Czarnota et al. 2001; Siegler 2006; Summers et al. 2009). It is generally accepted that allelopathy results from the release of specific chemicals that influence such factors as seed germination, radicle and hypocotyl elongation, and seedling growth and development (Einhellig and Souza 1992; Geneve and Weston 1988; Weston 2005). The effect of such chemicals gradually diminishes as they are leached below the root zone by irrigation or rainfall (Diab 2003), or microbially degraded following tissue disruption and/or burial in soil (Summers et al. 2009). This phenomenon of enhanced degradation was clearly demonstrated by the comparatively milder, and less persistent, deleterious activity of sudex residues when shredded and/or soil-incorporated in the present study.

The broad-spectrum, biocidal/biostatic activity demonstrated by these agronomically important, poaceous plants presents a challenge to those wishing to maximize their promising pest control potential, without having to worry about subsequent crop phytotoxicity. Clearly, there is a range of allelopathic or biotoxic activity in poaceous plants, and presumably across cultivars of specific taxa as well. Phytotoxicity to subsequent crops may not always occur, or be noticeable in the field if it does. In crop rotations with long fallow periods, or with satisfactory leaching, even rotations into highly bioactive varieties, such as sudex, may present no problems for subsequent crops. In the case of a planned fallow, it may be advantageous to begin the crop-free period with a bioactive, poaceous crop to discourage weed growth and/or reduce populations of soilborne nematodes or fungal propagules.

Future efforts to enhance agricultural sustainability will include development of strategies for crop multi-tasking, i.e., maximizing uses for both harvested and non-harvested portions (Jenkins et al. 2009; Stapleton and Bañuelos 2009). Biological and physical alternatives to synthetic chemical soil disinfestation can be important components of crop multi-tasking. However, alternatives that will be attractive to growers for implementation must provide predictable and relatively rapid reductions of pathogen/pest inocula, at reasonable cost, and without harming subsequent crops or soil quality. Development of guidelines for the pesticidal use of cultivated grasses, such as those tested here, as well as other members of the Poaceae, can contribute to these goals.

References

Ben-Hammouda, M., Kremer, R. J., & Minor, H. C. (1995). Phytotoxicity of extracts from sorghum plant components on wheat seedlings. Crop Science, 35, 1652–1656.

Burgos, N. R., & Talbert, R. E. (1996). Weed control and sweet corn (Zea mays var. rugosa) response in a no-till system with cover crops. Weed Science, 44, 355–361.

Cheema, Z. A., & Khaliq, A. (2000). Use of sorghum allelopathic properties to control weeds in irrigated wheat in a semi arid region of Punjab. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 79, 105–112.

Creamer, N. G., Bennett, M. A., Stinner, B. R., Cardina, J., & Regnier, E. E. (1996). Mechanisms of weed suppression in cover crop-based production systems. HortScience, 31, 410–413.

Czarnota, M. A., Paul, N., & Dayan, F. E. (2001). Mode of action, localization of production, chemical nature and activity of sorgoleone: a potent PSII inhibitor in Sorghum spp. root exudates. Weed Technology, 15, 813–825.

Davis, J. R., Huisman, O. C., Westermann, D. T., Hafez, S. L., Everson, D. O., Sorensen, L. H., et al. (1996). Effects of green manures on Verticillium wilt of potato. Phytopathology, 86, 444–453.

Del Moral, R. (1975). Allelopathy: a milestone monograph. Ecology, 56, 1231–1233.

Diab, N. (2003). Targeted mowing as a weed management method increasing allelopathy in rye (Secale cereale L.). Organic farming research foundation, Santa Cruz, CA, USA. http://ofrf.org/funded/reports/diab01s18.pdf.

Doohan, F. M., Mentebab, A., & Nicholson, P. (2000). Antifungal activity toward Fusarium culmorum in soluble wheat extracts. Phytopathology, 90, 666–671.

Dover, K., Wang, K.-H., & McSorley, R. (2004). Nematode management using sorghum and its relatives. University of Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN531

Einhellig, F. A., & Souza, I. F. (1992). Phytotoxicity of sorgoleone found in grain sorghum root exudates. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 18, 1–12.

Forney, D. R., & Foy, C. L. (1985). Phytotoxicity of products from rhizospheres of a sorghum sudangrass hybrid (Sorghum bicolor x Sorghum sudanense). Weed Science, 33, 597–604.

Gamliel, A., & Stapleton, J. J. (1993). Characterization of antifungal volatile compounds evolved from solarized soil amended with cabbage residues. Phytopathology, 38, 899–905.

Geneve, R. L., & Weston, L. A. (1988). Growth reduction of eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis L.) seedlings caused by interaction with a sorghum-sudangrass hybrid (Sudex). Journal of Environmental Horticulture, 6, 24–26.

Gomez, L. D., Steele-King, C. G., & McQueen-Mason, S. J. (2008). Sustainable liquid biofuels from biomass: the writings on the walls. New Phytologist, 178, 473–485.

Guenzi, W. D., McCalla, T. M., & Norstadt, F. A. (1967). Presence and persistence of phytotoxic substances in wheat, oat, corn, and sorghum residues. Agronomy Journal, 59, 163–165.

Iyer, J. G. (1980). Sorghum-sudan green manure; its effect on nursery stock. Plant and Soil, 54, 159–162.

Jenkins, B. M., Somerville, C., & Stapleton, J. J. (2009). Biofuels: growing toward sustainability. California Agriculture, 63, 155–158. Available online: http://californiaagriculture.ucanr.org/fileaccess.cfm?article=72726&p=NPCLJT&filetip=pdf.

Lynch, J. M. (1977). Phytotoxicity of acetic acid produced in the anaerobic decomposition of wheat straw. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 42, 81–87.

Mallek, S. B., Prather, T. S., & Stapleton, J. J. (2007). Interactions among Allium spp. soil amendments and concentrations, temperature, and exposure time on weed seed viability. Applied Soil Ecology, 37, 233–239.

Miller, D. A. (1996). Allelopathy in forage crop systems. Agronomy Journal, 88, 854–859.

Patrick, Z. A., Toussoun, T. A., & Snyder, W. C. (1963). Phytotoxic substances in arable soil associated with decomposition of plant residues. Phytopathology, 53, 152–161.

Putnam, A. R., & DeFrank, J. (1983). Use of phytotoxic plant residues for selective weed control. Crop Protection, 2, 173–181.

Siegler, D. S. (2006). Basic pathways for the origin of allelopathic compounds. In M. J. Reigosa, N. Pedrol & L. González (Eds.), Allelopathy: A physiological process with ecological implications (pp. 11–61). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Snapp, S. S., Date, K. U., Kirk, W., O’Neil, K., Kremen, A., & Bird, G. (2007). Root, shoot tissues of Brassica juncea and Cereale secale promote potato health. Plant and Soil, 294, 55–72.

Stapleton, J. J. (2000). Soil solarization in various agricultural production systems. Crop Protection, 19, 837–841.

Stapleton, J. J. (2006). Biocidal and allelopathic properties of gramineous crop residue amendments as influenced by soil temperature. In Proceedings, California conference on biological control V (Riverside, CA, USA), pp. 179–181. Available online: http://www.cnr.berkeley.edu/biocon/Complete%20Proceedings%20for%20CCBC%20V.pdf

Stapleton, J. J., & Bañuelos, G. S. (2009). Biomass crops can be used for biological disinfestation and remediation of soils and water. California Agriculture, 63, 41–46. Available online: http://californiaagriculture.ucanr.org/fileaccess.cfm?article=65637&p=CTQZGI&filetip=pdf.

Stapleton, J. J., & Duncan, R. A. (1998). Soil disinfestation with cruciferous amendments and sublethal heating: Effects on Meloidogyne incognita, Sclerotium rolfsii, and Pythium ultimum. Plant Pathology, 47, 737–742.

Summers, C. G., Mitchell, J. P., Prather, T. S., & Stapleton, J. J. (2009). Sudex cover crops can kill and stunt subsequent tomato, lettuce and broccoli transplants through allelopathy. California Agriculture, 63(1), 35–40.

Waddington, J. (1978). Growth of barley, bromegrass and alfalfa in the greenhouse in soil containing rapeseed and wheat residues. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 58, 241–248.

Wardle, D. A., Nicholson, K. S., & Rahman, A. (1996). Use of a comparative approach to identify allelopathic potential and relationship between allelopathy bioassays and “competition” experiments for ten grassland and plant species. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 22, 933–947.

Weston, L. A. (2005). History and current trends in the use of allelopathy for weed management. HortTechnology, 13, 529–534.

Weston, L. A., Harmon, R., & Mueller, S. (1989). Allelopathic potential of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid (Sudex). Journal of Chemical Ecology, 15, 1855–1865.

Widmer, T. L., & Abawi, G. S. (2000). Mechanism of suppression of Meloidogyne hapla and its damage by a green manure of sudan grass. Plant Disease, 84, 562–568.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Ashcroft, D. Dougherty, R. Duncan, R. Gill, S. Kaku, S. Mallek, A. Newton, T. Ruiz, R. Smith and S. Stapleton for technical assistance; Michael McKenry for kind provision of nematode analysis resources; and the late Carol Adams for statistical advice. The partial financial support of these studies by the State of California, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Pesticide Regulation; the California Tomato Commission; and the UC Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program, is greatly appreciated.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Stapleton, J.J., Summers, C.G., Mitchell, J.P. et al. Deleterious activity of cultivated grasses (Poaceae) and residues on soilborne fungal, nematode and weed pests. Phytoparasitica 38, 61–69 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-009-0070-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-009-0070-3