Abstract

Background

The study of sedentary behavior is a relatively new area in population health research, and little is known about patterns of sitting time on week-days and weekend-days.

Purpose

To compare self-reported week-day and weekend-day sitting time with reported weekly time spent in other activities.

Method

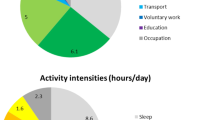

Data were from 8,717 women born between 1973 and 1978 (‘younger’), and 10,490 women born between 1946 and 1951 (‘mid-age’) who completed surveys for the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health in 2003 and 2001, respectively. They were asked about time spent sitting on week-days and weekend-days. The women were also asked to report time spent in employment, active leisure, passive leisure, home duties, and studying. Mean week-day and weekend-day sitting times were compared with time-use using analysis of variance.

Results

Younger women sat more than mid-aged women, and sitting time was higher on week-days than on weekend-days in both cohorts. There were marked positive associations between week-day and weekend-day sitting times and time spent in passive leisure in both cohorts, and with time spent studying on week-days for the younger women. Week-day sitting time was markedly higher in women who reported >35 h in employment, compared with those who worked <35 h. In contrast, there were inverse associations between sitting time and time spent in home duties. Associations between sitting and active leisure were less consistent.

Conclusion

Although week-day sitting time was higher than weekend-day sitting time, the patterns of the relationships between week-day and weekend-day sitting and time-use were largely similar, except for time spent in employment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Blanck HM, McCullough ML, Patel AV, Gillespie C, Calle EE, Cokkinides VE, et al. Sedentary behavior, recreational physical activity, and 7-year weight gain among postmenopausal U.S. women. Obesity. 2007;15(6):1578–88.

Brown WJ, Williams L, Ford JH, Ball K, Dobson AJ. Identifying the energy gap: magnitude and determinants of 5-year weight gain in midage women. Obes Res. 2005;13(8):1431–41.

Giles-Corti B, Macintyre S, Clarkson JP, Pikora T, Donovan RJ. Environmental and lifestyle factors associated with overweight and obesity in Perth, Australia. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18(1):93–102.

Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1785–91.

Jakes RW, Day NE, Khaw KT, Luben R, Oakes S, Welch A, et al. Television viewing and low participation in vigorous recreation are independently associated with obesity and markers of cardiovascular disease risk: EPIC–Norfolk population-based study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(9):1089–96.

Salmon J, Bauman A, Crawford D, Timperio A, Owen N. The association between television viewing and overweight among Australian adults participating in varying levels of leisure-time physical activity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(5):600–6.

Kronenberg F, Pereira MA, Schmitz MK, Arnett DK, Evenson KR, Crapo RO, et al. Influence of leisure time physical activity and television watching on atherosclerosis risk factors in the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2000;153(2):433–43.

Bertrais S, Beyeme-Ondoua JP, Czernichow S, Galan P, Hercberg S, Oppert JM. Sedentary behaviors, physical activity, and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged French subjects. Obes Res. 2005;13(5):936–44.

Ford ES, Kohl III HW, Mokdad AH, Ajani UA. Sedentary behavior, physical activity, and the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Obes Res. 2005;13(3):608–14.

Healy GN, Wijndaele K, Dunstan DW, Shaw JE, Salmon J, Zimmet PZ, et al. Objectively measured sedentary time, physical activity, and metabolic risk: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Diab Care. 2008;31(2):369–71.

Ekelund U, Brage S, Besson H, Sharp S, Wareham NJ. Time spent being sedentary and weight gain in healthy adults: reverse or bidirectional causality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(3):612–7.

IPAQ Core Group. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Available at: URL: http://www.ipaq.ki.se. Accessed 27/01/2009.

Pate RR, O'Neill JR, Lobelo F. The evolving definition of "sedentary". Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2008;36(4):173–8.

Rosenberg DE, Bull FC, Marshall AL, Sallis JF, Bauman AE. Assessment of sedentary behavior with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5 Suppl 1:S30–44.

Lee C, Dobson AJ, Brown WJ, Bryson L, Byles J, Warner-Smith P, et al. Cohort profile: the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(5):987–91.

Brown WJ, Bryson L, Byles JE, Dobson AJ, Lee C, Mishra G, et al. Women's Health Australia: recruitment for a national longitudinal cohort study. Women Health. 1998;28(1):23–40.

Brown WJ, Bauman AE. Comparison of estimates of population levels of physical activity using two measures. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(5):520–5.

Brown WJ, Burton NW, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Reliability and validity of a modified self-administered version of the Active Australia physical activity survey in a sample of mid-age women. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(6):535–41.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski N, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, USA; 1993.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Standard Classification of Occupations (ASCO). 1997, Canberra, Australia.

van Uffelen JG, Watson MJ, Dobson AJ, Brown WJ. Sitting time is associated with weight, but not with weight gain in mid-aged Australian women. Obesity 2010 January 28 [Epub ahead of print].

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95.

Schneider S, Becker S. Prevalence of physical activity among the working population and correlation with work-related factors: results from the first German National Health Survey. J Occup Health. 2005;47(5):414–23.

Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(2 Suppl):S1–14.

Clark BK, Sugiyama T, Healy GN, Salmon J, Dunstan DW, Owen N. Validity and reliability of measures of television viewing time and other non-occupational sedentary behaviour of adults: a review. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):7–16.

Tudor-Locke CE, Myers AM. Challenges and opportunities for measuring physical activity in sedentary adults. Sports Med. 2001;31(2):91–100.

Acknowledgments

The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH), which was conceived and developed by groups of interdisciplinary researchers at the Universities of Newcastle and Queensland, is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The funding source had no involvement in the research presented in this manuscript.

Jull was supported by an (Australian) National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) program grant (#301200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Uffelen, J.G.Z., Watson, M.J., Dobson, A.J. et al. Comparison of Self-Reported Week-Day and Weekend-Day Sitting Time and Weekly Time-Use: Results from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Int.J. Behav. Med. 18, 221–228 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-010-9105-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-010-9105-x