Abstract

Introduction

Influenza is a common and potentially serious disease in children. This retrospective cohort study examined the incidence of complications and associated risk factors in this population, and the effects of antiviral treatment.

Methods

Data for children aged ≤17 years with a clinical diagnosis of influenza (ICD-9-CM codes 487.xx or 488.xx) during the 2006–2010 influenza seasons (including the 2009–2010 pandemic season) were obtained from US insurance claims databases. Unconditional logistic regression was used to evaluate the effect of antiviral treatment on the incidence of complications and healthcare resource utilization during the 30 days post the index influenza diagnosis. A sub-analysis in children aged <1 year was performed.

Results

Antiviral treatment was used in 315,128 (39.53%) of 797,284 cases. The risk of complications was higher in children with pre-existing conditions, e.g., asthma (odds ratio [OR] = 1.86) or cystic fibrosis (OR = 1.67) than otherwise healthy children. Antiviral treatment reduced the 30-day risk of complications, hospitalization, emergency department visits, and ≥2 outpatient visits versus no treatment (ORs = 0.76, 0.69, 0.76, and 0.81, respectively); 30-day risks were further reduced by early treatment (within 2 days of diagnosis). The sub-analysis included 19,666 children aged <1 year; 7.38% received antiviral treatment during the pre-pandemic seasons and 33.00% during the pandemic season. Findings were similar to the main analyses; however, healthcare resource utilization was only significantly reduced by early treatment.

Conclusions

Antiviral treatment is associated with reduced risk of complications and healthcare resource utilization in children of all ages with influenza, especially when initiated early.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although influenza viruses cause infections in all age groups, there is a considerable disease burden in children [1]. This burden is concentrated in younger children, and in particular children aged <2 years, in whom complications associated with influenza occur most frequently [2]. Each year approximately 20,000 children aged <5 years are hospitalized due to complications of influenza [2], and many studies have shown that rates of hospitalization and death are higher in younger versus older children, both in seasonal and pandemic influenza [3–7]. The risk of serious complications and hospitalization in influenza-infected children is higher in those with co-existing chronic conditions, such as asthma and disorders of the nervous system, than in otherwise healthy children [2, 8–10].

This paper reports a retrospective claims-based cohort analysis in children aged <18 years with a clinical diagnosis of influenza. Its aims were to describe the incidence of clinical complications and associated risk factors in this population, and the effect of antiviral treatment on the risk of complications and measures of healthcare utilization such as hospitalization. We followed the common age categories for reporting pediatric influenza incidence according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): 0–4; 5–12, and 13–17 years. Furthermore, results of a subgroup analysis in children aged <1 year are also presented, since few studies have focused on this especially vulnerable population, who have higher rates of influenza-related hospitalizations than older children [3, 11]; inclusion of this subgroup with children >1 year of age obscures both this enhanced risk and the unknown effect of antiviral therapy. In general, antiviral treatment is not approved for use in this age group, with the exception of the USA, where oseltamivir was approved in December 2012 for all children aged ≥2 weeks. However, during the H1N1pdm2009 pandemic, emergency use authorizations that were issued by the US CDC, European Medicines Agency, and Health Canada permitted the use of oseltamivir in children aged <1 year. We, therefore, compared complication data from the pandemic period with those from the three previous seasons in this age group.

Methods

Data Source

This was a retrospective cohort study based on insurance claims data for US patients taken from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, Medicare Supplemental Database and MarketScan Co-ordination of Benefits Database (Thomson Reuters, Cambridge, MA). Together, these databases covered 124,096,527 lives. The patients whose records are in these databases are mostly private payers and individuals covered by Medicare.

Enrollment/eligibility records for each patient contain demographic information, including age, gender, and census region, while the medical claims files capture information on inpatient and outpatient care and the use of facilities and services, including the date and place of service, provider type, and payment information. Each medical claim is associated with up to 15 ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification) diagnosis codes and up to 15 ICD-9-CM procedure codes. Pharmacy claims files capture the National Drug Code, dispensing date, quantity of drug and number of days supplied, and payments made.

Data Selection and Screening

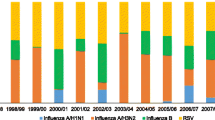

For this analysis, the index date was defined as the date of first influenza diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes with prefix 487 or 488) to be billed in an influenza season. Data included in the analysis were from patients aged <18 years for whom the index date occurred between October 1 and March 31 in any of the three Northern Hemisphere influenza seasons 2006–2007, 2007–2008, and 2008–2009, and during the 12 months of the H1N1pdm09 influenza pandemic (April 1, 2009 to March 31, 2010) according to the CDC [12]. These records were further screened to exclude duplicate records, patients who did not meet insurance eligibility requirements (i.e., <3 months of continuous health insurance coverage before the index date, or <30 days of health insurance coverage after the index date), and those with an index date falling on the same day as an influenza vaccination.

We quantified patients who were diagnosed with a chronic pulmonary disease (asthma, bronchitis, cystic fibrosis, and other chronic respiratory diseases), heart disease (cardiac disease and heart failure), diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, renal disease, or immunocompromised disease state before the index date. For all included patients, records were searched during the 30 days after the index date to identify any complications, identify antibiotic use, and assess healthcare resource utilization. The complications examined were selected from the ICD-9 codes used in the study by Loughlin’s group (Table 1) [13]. Briefly, acute respiratory infection (ARI) includes acute sinusitis, nasopharyngitis, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, laryngitis and tracheitis, upper respiratory infection, acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis, and acute pneumonia.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed for three age groups (0–4, 5–12, and 13–17 years) according to the CDC commonly used age categories. To examine the emergency use of antivirals during the H1N1pdm2009 pandemic, a subgroup analysis was performed in children aged <1 year.

The incidence rate of each complication was calculated as the number of patients affected divided by the total time for which patient data were recorded in the database (in patient-months) during each influenza season. Unconditional logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate whether antiviral treatment (i.e., oseltamivir and zanamivir) had any effect on the risk of developing complications during the 30 days post the index influenza diagnosis. For these analyses, the dependent variable was the complication (present or not present) and the independent variable was antiviral treatment (yes or no). The covariates were: age, gender, region (North-East, North central, South, West or unknown), health plan (Exclusive Provider Organization, Preferred Provider Organizations, Health Maintenance Organization, Point of Service, Consumer Driven Health Plan or High Deductible Health Plan), influenza season (2006–2007, 2007–2008, 2008–2009 or 2009–2010 [pandemic]), influenza vaccination, pre-existing conditions (chronic respiratory disease [asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis], heart disease [congestive heart failure and ischemic heart disease], diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or immunocompromised disease state recorded prior to the first influenza diagnosis), and other treatment (antibiotics, antipyretics, nasal decongestants, ear drops, cough medication or throat preparation).

Additional logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the effect of antiviral treatment on three measures of 30-day healthcare utilization, i.e., the number of patients admitted to hospital or the emergency department at least once, and the number of patients who made ≥2 outpatient visits. The dependent variable was the healthcare utilization measure, the independent variable was antiviral treatment and the covariates were gender (male, female), age group (0–4, 5–12, and 13–17 years, except in the sub-analysis of children aged <1 year), region, and health insurance coverage. For all regression analyses, adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to compare risks. For time to start antiviral treatment, the interval between influenza diagnosis and prescription fill was used (measured in whole days), as the date of illness onset was not available in the claims record.

SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform the data analyses. The significance level was set at a two-tailed alpha value of 0.05.

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Total Cohort

Demographic Data, Pre-Existing Conditions, and Treatment Patterns

The main cohort consisted of 797,284 cases of clinically diagnosed influenza (Fig. 1). The largest age group was children aged 5–12 years, which contained more children than the other two groups combined (0–4 years and 13–17 years; Table 2). The majority of children were otherwise healthy, with no co-morbidities. The most common pre-existing condition was asthma, the prevalence of which was similar across the three age groups (11–14%), with other chronic pulmonary diseases affecting 4–6% of children (Table 1).

Influenza was treated with antivirals in 315,128 (39.53%) cases, with oseltamivir accounting for 94.66% of all treatments (Table 2). The proportion of children treated was similar across age groups. Antiviral treatment was started within 2 days of influenza diagnosis in 93.51% of all cases. The mean time from diagnosis to prescription fill was <0.25 days in all three age groups and the mean duration of treatment ranged from 5.55 to 5.99 days.

Complication Rates and Risk Factors

The most commonly reported 30-day complication across all age groups was ARI (13.33%); this complication was nearly twice as prevalent in children aged 0–4 years as in adolescents. Acute otitis media (AOM) was reported in almost 10% of children aged 0–4 years but less commonly in children >4 years old. Asthma was the only other complication occurring in >1% of cases, being slightly less common in adolescents than younger children (Table 3).

Compared with children aged 0–4 years, older children had a significantly lower risk of a complication, with ORs of 0.55 (95% CI: 0.54–0.56) and 0.42 (95% CI: 0.41–0.43) in the 5–12 years and 13–17 years age groups, respectively (P < 0.0001 in both cases) (Table 4). For all of the pre-existing conditions analyzed, the risk of a complication was significantly higher in children with pre-existing conditions than those without. The increase in relative risk was particularly marked for respiratory disease, with ORs of 1.86 for asthma and 1.67 for cystic fibrosis. Complication risk was also significantly higher in vaccinated than unvaccinated children and in antibiotic users compared with non-users (P < 0.0001 in both cases).

Effect of Antiviral Treatment on Complications

Antiviral treatment significantly reduced the risk of an influenza complication across the total cohort, compared with no antiviral treatment (OR = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.75–0.77). The reduction in risk was also significant for some specific complications, e.g., ARI (OR = 0.78; 95% CI: 0.77–0.79) and AOM (OR = 0.63; 95% CI: 0.61–0.65; Table 5). The risk of complications was much lower in children whose prescriptions for antiviral treatments were filled within 2 days of diagnosis than in those whose prescriptions were filled later (OR = 0.21; 95% CI: 0.19–0.29; Table 6).

Effect of Antiviral Treatment on Use of Healthcare Resources

For the total cohort, children who received antiviral treatment had significantly lower risks of hospitalization (OR = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.66–0.73), emergency department visits (OR = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.75–0.77), and making ≥2 outpatient clinic visits (OR = 0.81; 95% CI: 0.80–0.82), compared with those who received no antiviral treatment (Table 6). Early initiation of antiviral treatment (within 2 days of diagnosis versus later) was associated with even larger reductions in risk of these three outcomes (Table 6).

Subgroup Analysis, Children Aged <1 Year Old

Demographic Data, Pre-Existing Conditions, and Treatment

A total of 19,666 children aged <1 year were eligible for analysis, divided almost equally between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. Asthma (prevalence: 3.57–4.56%) and other chronic pulmonary diseases excluding cystic fibrosis (prevalence: 2.75–3.71%) were the most common pre-existing conditions in both time periods (Table 7).

The proportion of infants treated with antivirals was more than four times higher in the pandemic period than the pre-pandemic period (33.00% vs. 7.38%); oseltamivir accounted for 88.7% of all antivirals prescribed pre-pandemic, and 99.7% during the pandemic. The proportion of all antivirals started within 2 days of influenza diagnosis increased from 86.8% of cases (pre-pandemic) to 98.2% in the pandemic, resulting in a lower mean time from diagnosis to prescription fill in the latter period (Table 7).

Complication Rates and Risk Factors

The majority of complications in this age group were either ARI or AOM. The latter appeared slightly less common during the pandemic (16.08%) than before it (21.48%), but the prevalence of ARI was similar in the two periods. With the exception of asthma, other complications occurred in less than 0.4% of children (Table 8).

In children aged <1 year, the complication rate was slightly but significantly lower during the pandemic than the three seasons before it (OR = 0.91; 95% CI: 0.85–0.97; P = 0.004), and girls were also significantly less likely to have a complication than boys (OR = 0.88; 95% CI: 0.83–0.94; P < 0.0001; Table 9). As in the analysis of the total cohort, the complication rate was significantly higher in infants who received vaccination and those who received antibiotics, and significantly lower in those who received antivirals (OR = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.74–0.87; P < 0.0001) for infants in both periods combined. Three of the eight pre-existing conditions analyzed showed a significant association with complication rate: ORs for asthma, other chronic pulmonary diseases, and cystic fibrosis were 1.83 (95% CI: 1.57–2.14), 1.21 (95% CI: 1.02–1.44), and 4.69 (95% CI: 1.26–17.53), respectively, compared with otherwise healthy infants (Table 9).

Effect of Antiviral Treatment on Complications

Antiviral treatment significantly reduced the risk of complication both before the pandemic (OR = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.51–0.72) and during it (OR = 0.88; 95% CI: 0.80–0.97). In the analysis of specific complications, however, a significant reduction in risk in both periods was seen for AOM only (ORs of 0.58 [95% CI: 0.47–0.71] and 0.67 [95% CI: 0.59–0.76], respectively). For ARI, the most common complication, risk reduction was significant only in the pre-pandemic period (OR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.60–0.85; Table 10).

Effect of Antiviral Treatment on Use of Healthcare Resources

The risk of hospitalization or emergency department visits was not significantly lower in children aged <1 year who received antiviral treatment than those who did not, either before or during the pandemic. The risk of ≥2 outpatient visits was significantly lower in infants who received antiviral treatment compared with those who did not, but only during the pre-pandemic period (Table 11). By contrast, in both pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, the risk of hospitalization and ≥2 outpatient visits was significantly lower in infants for whom prescriptions were filled within 2 days of diagnosis versus later (Table 11). The corresponding risk reduction for emergency department visits was also significant, but only during the pre-pandemic period (OR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.16–0.80; Table 11).

Discussion

Our retrospective analysis of claims data in children in the US showed that the incidence of all influenza-related complications was at least twice as high in those aged 0–4 years than in older children (32 events per 100 person-months vs. 17 in children aged 5–12 years and 13 in those aged 13–17 years). This age-related difference was also evident when comparing rates of the two most common complications in children aged <1 year with those in the total cohort. ARI occurred in approximately 30% of children aged <1 year during the pandemic and pre-pandemic periods, more than double the rate (13.33%) in the whole cohort, and the same contrast was seen with AOM, whose prevalence was markedly higher in the <1-year-old population (21.48% in the pre-pandemic period) than in all children (3.93%).

All the pre-existing conditions analyzed in our regression models significantly increased the 30-day risk of influenza complications in the total cohort compared with children with no pre-existing conditions. The largest increases were for asthma and cystic fibrosis, with ORs of 1.86 (95% CI: 1.83–1.89) and 1.67 (95% CI: 1.36–2.05), respectively. Regression analysis also found significant associations between the rate of complications and whether or not children had received influenza vaccination and antibiotics. These observations may reflect a well-described selection bias, since higher-risk children, who have a greater complication risk [5], are defined in treatment guidelines as priority cases for vaccination, and would be expected to have higher rates of infectious disease complications and greater antibiotic utilization. It is also possible that the adjustments made to the regression analysis for pre-existing conditions may not have fully corrected for a risk bias in the vaccinated cohort.

In the total cohort, approximately 40% of children received antiviral therapy, typically with oseltamivir. Antiviral treatment was associated with significant reductions in the risk of complications and of hospitalizations (ORs of 0.76 [95% CI: 0.75–0.77] and 0.69 [95% CI: 0.66–0.73] compared with no antiviral treatment). These findings broadly agree with those of an earlier retrospective claims study of similar design based on data from 6 influenza seasons (2000–2001 to 2005–2006) [14]; despite the much smaller cohort size (~5,350 children aged 1–17 years), that study found that the risk of respiratory illnesses (other than pneumonia), otitis media and its complications, and all-cause hospitalizations was lower in the oseltamivir-treated cohort than untreated children. An earlier prospective study in children aged 1–12 years by Whitley et al. [15], which used a randomized controlled design, also found significantly lower rates of physician-diagnosed complications, notably AOM, in oseltamivir-treated patients than in placebo recipients. AOM incidence was also significantly lower in oseltamivir-treated children aged 1–3 years in a Swedish placebo-controlled study, although only in a subgroup in which treatment was started within 12 h of illness onset [16].

In our sub-analysis in children aged <1 year, the risk of developing complications was significantly reduced by antiviral treatment both before and during the pandemic; however, the OR was lower (suggesting greater risk reduction) in the pre-pandemic period (0.61 [95% CI: 0.51–0.72] vs. 0.88 [95% CI: 0.80–0.97]). A possible explanation is that more children with milder disease were treated with antivirals during the pandemic and that this may have diluted the complication risk. This is supported by the finding that children aged <1 year were much more likely to be given antiviral treatment during the pandemic period year than in the previous three influenza seasons, and the proportion who started treatment within the 2-day window was also larger during the pandemic. This reflected treatment guidelines issued by US CDC in May 2009 that recommended children aged <5 years as one of the priority groups that should be tested and given antiviral treatment if H1N1pdm09 infection was suspected [17]. Due to our requirement for ≥3 months continuous health insurance coverage before the index data, infants <3 months were not included in the analyses.

One of the strengths of our study is the sample size: with 315,000 children treated with antivirals, this is the largest study in children with clinically diagnosed influenza aged <18 years with adequate numbers to assess the event rates of complications based on retrospective, claims-based analysis. As the time of illness onset in each patient was not known, we measured the time to initiation of antiviral therapy from the date of diagnosis; thus, the threshold value of 2 days used to define early versus late treatment in our analysis was almost certainly an underestimate of the time from illness onset. Despite this, the differences in the rate of complications and healthcare use between earlier and later treatment starters were marked and statistically significant. The size of this difference may reflect the nature of the claims data available and in particular the time to treatment, as mentioned above.

A claims database analysis has its own limitations. This was a retrospective, non-randomized study using clinical diagnosis of influenza and reported associated complications without verification by laboratory methods. The sensitivity and specificity of ICD-9 codes for influenza diagnosis are not established for a confirmed influenza illness. We may also have incorrectly estimated the risk of secondary complications based on a clinical diagnosis alone and the potential that treated cases were likely to be reported. The risk of complications seen in those with pre-existing diseases may have been overestimated because such patients may be more likely to see a physician and be diagnosed with influenza. A claims database analysis may also underestimate the overall incidence of complications because not all patients with influenza seek a physician’s care.

Conclusion

Our data indicate a substantial beneficial association of antiviral treatment with the risk of influenza complications and healthcare utilization, in line with previously published studies, and emphasize the importance of early initiation of treatment for achieving additional benefit.

References

Ruf BR, Knuf M. The burden of seasonal and pandemic influenza in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:265–76.

CDC. Children, the flu, and the flu vaccine. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/children.htm. Accessed 29 Oct 2013.

Ampofo K, Gesteland PH, Bender J, et al. Epidemiology, complications, and cost of hospitalization in children with laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2409–17.

Bhat N, Wright JG, Broder KR, et al. Influenza-associated deaths among children in the United States, 2003–2004. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2559–67.

Mullooly JP, Barker WH. Impact of type A influenza on children: a retrospective study. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:1008–16.

Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Griffin MR, et al. The burden of influenza in young children, 2004–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;131:207–16.

Sachedina N, Donaldson LJ. Paediatric mortality related to pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: an observational population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:1846–52.

Coffin SE, Zaoutis TE, Rosenquist AB, et al. Incidence, complications, and risk factors for prolonged stay in children hospitalized with community-acquired influenza. Pediatrics. 2007;119:740–8.

Neuzil KM, Wright PF, Mitchel EF Jr, Griffin MR. The burden of influenza illness in children with asthma and other chronic medical conditions. J Pediatr. 2000;137:856–64.

Weigl JA, Puppe W, Schmitt HJ. The incidence of influenza-associated hospitalizations in children in Germany. Epidemiol Infect. 2002;129:525–33.

Chiu SS, Lau YL, Chan KH, Wong WH, Peiris JS. Influenza-related hospitalizations among children in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2097–103.

CDC. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic: summary highlights, April 2009–2010. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/cdcresponse.htm. Accessed 29 Oct 2013.

Loughlin J, Poulios N, Napalkov P, Wegmuller Y, Monto AS. A study of influenza and influenza-related complications among children in a large US health insurance plan database. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:273–83.

Piedra PA, Schulman KL, Blumentals WA. Effects of oseltamivir on influenza-related complications in children with chronic medical conditions. Pediatrics. 2009;124:170–8.

Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, Reisinger KS, et al. Oral oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:127–33.

Heinonen S, Silvennoinen H, Lehtinen P, et al. Early oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children 1–3 years of age: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:887–94.

CDC. Updated interim recommendations for the use of antiviral medications in the treatment and prevention of influenza for the 2009–2010 season. http://www.cdc.gov/H1N1flu/recommendations.htm. Accessed 29 Oct 2013.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study and the article processing charges were provided by Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, in the form of a non-restrictive research grant to Tulane University. Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript, furnished by Roger Nutter and Lucy Carrier of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications, was provided by Genentech and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Mark Loveless is a former employee of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. Philip Spagnuolo is a former employee of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. Yaping Xu is a current employee of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. Er Chen is a current employee of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. Jian Han is a current employee of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. Lizheng Shi is an employee of Tulane University. Mengxi Zhang is an employee of Tulane University. Shuqian Liu is an employee of Tulane University. Jinan Liu is an employee of Tulane University. Tulane University received funding from Genentech for the current study.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, L., Loveless, M., Spagnuolo, P. et al. Antiviral Treatment of Influenza in Children: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Adv Ther 31, 735–750 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-014-0136-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-014-0136-6