Abstract

The fatty-acid-binding protein-2 (FABP2) gene has been proposed as a candidate gene for diabetes because the encoded protein is involved in fatty acid absorption and therefore may affect insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. The rare haplotype (B) of its promoter was shown to be associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes. The aim of this study was to investigate whether a polymorphism in the FABP2 promoter does affect the metabolic response to either an medium-chain triacylglycerol (MCT) or an long-chain triacylglycerol (LCT) diet, which were suggested to differ in transport mechanisms, in affinity to FABP2, in activating transcription factors binding to the FABP2 promoter and in their effects on insulin sensitivity. We studied 82 healthy male subjects varying in the FABP2 promoter (42 homozygous for common haplotype (A), 40 homozygous for the rare haplotype (B)) in an interventional study with either an MCT or LCT diet over 2 weeks to examine gene–nutrient interaction. The saturation grade of MCT was adjusted to that of the LCT fat. We determined glucose, insulin, triacylglycerols (TGs), chylomicron triacylglycerols and cholesterol before and after a standardised mixed meal before and after the intervention. HDL cholesterol increased in all groups, which was most pronounced in subjects homozygous for the common promoter haplotype A who received MCT diet (P = 0.001), but not significant in homozygous rare haplotype B subjects who received MCT fat. Subjects homozygous for FABP2 haplotype A showed a significant decrease in fasting and postprandial glucose (P = 0.01, 0.04, respectively) and a decrease in insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, P = 0.04) during LCT diet. After correction for multiple testing, those effects did not remain significant. Fasting and postprandial triacylglycerols, LDL cholesterol, chylomicron TGs and cholesterol were not affected by genotype or diet. MCT diet increased HDL cholesterol dependent on the FABP2 promoter haplotype. The effects of the promoter haplotype B could be mediated by PPARγ, which is upregulated by medium-chain fatty acids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intestinal fatty-acid-binding protein-2 (FABP2) regulates the intracellular concentration of free fatty acids (FA) in intestinal cells. It contains a single ligand binding site that has high affinity for saturated and unsaturated fatty acids (Baier et al. 1995). FABP2 transports FA from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum where the FA are esterified with glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) to form triacylglycerols (TGs). The TGs are incorporated into chylomicrons that are transported via lymph into the circulation. The FABP2 gene has been proposed as a candidate gene for type 2 diabetes because the encoded protein is involved in fatty acid absorption and therefore may affect insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism (Randle et al. 1963; Baier et al. 1995).

Numerous studies have assessed the association of FABP2 gene variants with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (Baier et al. 1995; Bach et al. 1996; Hegele et al. 1997; Agren et al. 1998; Marin et al. 2005). The association of a threonine coding FABP2 variant with insulin resistance appears to be confined to individuals who are consuming a high-fat diet (Ball 1993; Binnert et al. 1998). Another study found that Thr54 homozygous had a greater decrease in cholesterol and apoB during a diet high in soluble fibre than Ala54 homozygous subjects (Nosaka et al. 2003; Tholstrup et al. 2004).

Several studies found positive effects of MCT fat on body weight and weight control (Asakura et al. 2000); medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) are preferentially oxidised rather than deposited in adipose tissue triacylglycerols (Tholstrup et al. 2004). They increase thermogenesis and seem to increase satiety via increasing plasma levels of hydroxybutyrate (Hill et al. 1989; Van Wymelbeke et al. 2001). Conflicting results have been reported about the effects of chronic administration of MCT on plasma glucose, insulin, triacylglycerols and cholesterol levels (Eckel et al. 1992; Asakura et al. 2000); (Tholstrup et al. 2004; Marten et al. 2006; Han et al. 2007; Oikari et al. 2008). The discrepancies could be due to different study design or different genetic background of the study subjects (Marten et al. 2006). Moreover, differences, such as the type of fatty acid or fibre consumed with the background diet, might interact with functional differences due to genetic variation and may have resulted in phenotypic differences. However, another general limitation of former studies is the difference in saturation grade between the test diets. The content of saturated fat was much higher in MCT rather than LCT (mostly polyunsaturated) fats used in those intervention studies (Eckel et al. 1992; Asakura et al. 2000; Van Wymelbeke et al. 2001). This difference could have masked the positive effect of MCT. Additionally, the administered fats did not take into account the different caloric density of MCT and LCT fat.

There are six known polymorphisms in the promoter of the FABP2 gene, which are in perfect linkage disequilibrium (LD) and reside in two haplotypes (Geschonke et al. 2002; Damcott et al. 2003; Formanack and Baier 2004). We and others could show that the rare haplotype B in the FABP2 promoter is associated with insulin resistance (Helwig et al. 2007), type 2 diabetes (Formanack and Baier 2004; Li et al. 2006) and hypercholesterolemia (Damcott et al. 2003). Reporter gene assays indicated a higher responsiveness to PPARγ/RXR of FABP2 promoter B versus promoter A.

FABP preferentially binds long-chain fatty acids (Lowe et al. 1987; Richieri et al. 1994) but also medium-chain fatty acids (Huang et al. 2002), and its PPARγ induced promoter activity is dependent on genetic variation (Helwig et al. 2007). PPARγ is upregulated by medium-chain fatty acids (Yonezawa et al. 2004) and long-chain fatty acids itself and is therefore a target for gene–diet interaction studies. We hypothesised that subjects with a variation in FABP2 promoter haplotype might have different responses to medium- and long-chain fatty acid diets.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited with regard to their FABP2 promoter haplotype carrier-ship from a prospective intervention cohort, and the details of the recruitment were described recently (Rubin et al. 2010; Helwig et al. 2007). The study was approved by the Ethics committee of the University Clinic of Kiel. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. We selected 82 male, healthy unrelated subjects with regard to their FABP2 haplotype carrier-ship from the overall cohort consisting of 755 men. Inclusion criterion was male subjects with homozygosity for either of the FABP2 promoter haplotypes A or B. Exclusion criteria were as follows: known type 2 diabetes, diseases with impairment of nutrient digestion or metabolism, an intake of lipid-lowering drugs or hormones, visceral surgery in the past 3 months, hypo- or hyperthyroidism, chronic renal disease, hepatitis, cholestasis, alcoholism or cancer. Baseline characteristics of the subjects are given in Table 1. An OGTT was performed in all subjects in order to diagnose type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose metabolism.

None of the subjects was diabetic according to WHO guidelines (Alberti and Zimmet 1998). Forty-two subjects were homozygous for the common haplotype A and 40 subjects homozygous for the rare haplotype B. Out of the selected 82 subjects, 32 subjects were carriers of the rare exon genotype 12Thr. Forty-seven subjects were homozygous for exon genotype Ala12.

Diet

The subjects from the two genetic groups were randomised to receive either MCT- or LCT-based test fats, resulting in four test groups (haplotype A/LCT fat (n = 21), haplotype A/MCT fat (n = 21), haplotype B/LCT fat (n = 20), haplotype B/MCT fat (n = 20)) (Fig. 1). The saturation grade of the MCT fat was adjusted to that of the LCT fat by mixing MCT oil with high-oliec sunflower oil, resulting in a content of MCFA of 40%. The composition of the test fats are shown in Table 2. The LCT group received 40 g of fat, the MCT group 44 g fat, to secure isocaloric amounts of fat. Subjects were advised to exchange their habitual daily fat with the test fat and to maintain their habitual food pattern. Compliance was considered sufficient if the serum cholesterol fatty acid content for medium-chain fatty acids (C8–C12) after MCT diet or long-chain fatty acids (C16–C22) after LCT diet increased by at least 5%. Participants were instructed not to change their eating habits and physical activity routine, and not to use any dietary supplements of vitamins, minerals or special oil preparations. A 24-h food recall was performed on day 0 and day 14 as described in detail by (Johnson et al. 1996). Briefly, this recall consisted of a short list of all foods and drinks consumed, a detailed description and a review with the interviewer probing for information on time/occasion, forgotten foods and food details. Recalled portion sizes and household implements such as bowls were used to provide accurate estimates of consumption during a 24-h recall (Chambers et al. 2000).

Laboratory measurements

Blood was collected in the fasting state, 0.5 h postprandially (pp) and hourly until 9 h after ingestion of a standardised lipid load (oMTT) (Helwig et al. 2007; Rubin et al. 2008). The oMTT with a liquid volume of 500 ml contained the following ingredients: 30 g of protein (11.9 kcal%), 75 g of carbohydrate (29.6 kcal%; 93% sucrose, 7% lactose), 58 g of fat (51.6 kcal%; 65% saturated, 35% unsaturated fatty acids), 10 g of alcohol (6.9 kcal%), 600 mg cholesterol and 30,000 IU retinylpalmitate. The total energy content was 1,017 kcal (4,255 kJ). The fatty acid pattern (% w/w) of fat was as follows: caprone, 2%; capryl, 1.2%; caprine, 2.7%; laurine, 3%; myristine, 10.9%; palmitine, 28.4%; stearine, 13.1%; palmitoleine 2.4%; oleic, 27.1%; linolic, 2.4%; linolenic, 1.6%; acid and other fatty acids, 5.2%. Accordingly, the medium-chain fatty acids content was 8.9%. Serum and plasma was separated from whole blood by centrifugation (6°C, 10 min, 3000×g). Plasma and serum were stored at –20°C until analysis. Glucose and insulin were measured before and 30 min and every hour after meal ingestion; triacylglycerols and free fatty acids (NEFA) were assessed hourly during 9 h postprandially. Serum and chylomicron triacylglycerols, plasma glucose, fasting total cholesterol and chylomicron cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and liver enzymes were determined by standard enzymatic methods using Konelab 20i auto analyzer (Kone, Finland). Plasma insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay (Adaltis, Germany). All samples were measured in duplicate.

Chylomicrons (Sf > 400) were isolated according to Mills and Weech (1989), clearing factor k was 407. Briefly, plasma (4 ml) was layered beneath 4 ml sodium chloride (density 1.006 g/ml), placed in a TFT 70.13 rotor (Kontron) and centrifuged at 46.095×g (25.000 rpm) and kept at 15°C for 47 min. Chylomicrons in the top 2 ml were collected (Mills and Weech 1989).

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from 10 ml of frozen blood samples using the Gigakit DNA extraction kit (Invitec, Berlin, Germany). The following TaqMan® probes and primers were used: for the promoter site (rs2282688):

-

PCR forward primer: GGCAATGCTAAACACAATGCAAAA;

-

PCR reverse primer: TCACAACAGCAATTATCTTGTAAAGTAAGACT;

-

Taqman probe allele 1: AATCTTATTAACTTTAACTTTTC;

-

Taqman probe allele 2: TCTTATTAACTTTAGCTTTTC;

for the exon site (rs1799883):

-

PCR forward primer: AAGGAAGCTTGCAGCTCATGAC;

-

PCR reverse primer: CACCAAGTTCAAAAACAACTTCAATG,

-

Taqman probe allele 1: ATCAAGCACTTTTC;

-

Taqman probe allele 2: TCAAGCGCTTTTC.

All primers and probes were constructed by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). TaqMan® analysis was performed as described elsewhere (Hampe et al. 1999). In brief, genomic DNA was arrayed and dried on 96-well plates. TaqMan® PCR was performed using Genesis pipetting robots (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland), ABI 9700 PCR machines (Applied Biosystems) and ABI 7700 and ABI 7900 fluorimeters (Applied Biosystems).

Both polymorphisms, FABP2 A54T and promoter A/B, showed intermediate levels of linkage disequilibrium (D′ = 0.85, r 2 = 0.31). The genotypic concordance between both SNPs equalled 0.60.

Power analysis

Power analysis is provided for the variable with the maximum standard deviation (iNEFA). With a type I error of 0.05 and 80% power, the minimum of subjects per group was n = 17.

Statistical analyses

SPSS (SPSS for Windows, version 14.0.0, LEAD Technologies Inc.) was used for statistical analysis. Values in the text are expressed as mean ± SEM, and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. The 0–5 h and 0–9 h area under the curve (AUC), respectively, was calculated by the trapezoidal method.

Insulin sensitivity was estimated using the HOMA model: HOMA-R (insulin resistance): insulin (mU/l) × glucose (mmol/l)/22.5. In case of postprandial NEFA, the increase in NEFA (5–9 h) reflecting release from postprandially affluent triacylglycerols was calculated. Deviations from a normal distribution of parameters were tested by Kolmogoroff–Smirnoff test. Comparison of baseline parameters in the four intervention groups was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparisons of parameters on day 0 and day 14 in the groups were performed using a t test for normally distributed parameters and a Wilcoxon test for non-normally distributed parameters. Bonferroni–Holm correction was applied to correct for multiple testing.

Results

Anthropometric data

At baseline, the subjects of the four study groups did not differ in age, BMI, waist circumference or systolic blood pressure. The diastolic blood pressure was significantly different in the four groups (Table 1). As expected, BMI and waist were not significantly altered within 2 weeks intervention period. All subjects completed the study and reported having consumed the test fats. According to the 24-h recall, fat intake did not differ before and during the study within the groups (data not shown).

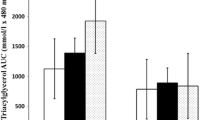

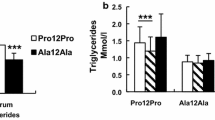

Cholesterol, triacylglycerol and free fatty acids

Table 3 shows the mean fasting concentrations of plasma cholesterol, triacylglycerols, glucose, insulin, HOMA and NEFA before and after the dietary intervention in the groups. At baseline, the four groups A/LCT (haplotype A/LCT diet), B/LCT (haplotype B/LCT diet), A/MCT (haplotype A/MCT diet) and B/MCT (haplotype B/MCT diet) did not significantly differ in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triacylglycerols and NEFA. In all subjects, HDL cholesterol increased after 2 weeks on the intervention diet, which was significant for all groups except the B/MCT group. After correction for multiple testing, only the A/MCT group showed a significant increase in HDL cholesterol (P = 0.001). Total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, fasting and postprandial triacylglycerols and NEFA did not change significantly during the intervention in either group (Table 3).

Glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR

Fasting and postprandial glucose decreased in FABP2 haplotype A carriers during intervention. This effect was significant only in subjects receiving the LCT diet (P = 0.01, P = 0.04, respectively). Accordingly insulin resistance, expressed as HOMA-IR, decreased significantly in this group, but not in the other groups (P = 0.04). The haplotype A subjects had a higher decrease in postprandial glucose concentrations after LCT diet (Table 3). However, accounting for multiple testing resulted in loss of significance for differences in glucose and HOMA-IR.

Discussion

Our study focused on the functional impact of FABP2 promoter polymorphisms on the response to a diet, to analyse whether oral intake of MCT or LCT fat altered the effects on glucose and lipid metabolism caused by the reported functional differences attributable to these SNPs.

There are six known polymorphisms in the promoter of the FABP2 gene, which are in perfect linkage disequilibrium (LD) and reside in two haplotypes (Geschonke et al. 2002; Damcott et al. 2003; Formanack and Baier 2004). Recent studies showed that the FABP2 promoter haplotype has some impact on postprandial lipemia, depending on the Thr54Ala exon polymorphism allele (Helwig et al. 2007). It was shown that variation in the FABP2 promoter affects gene expression, which could have implications for prior association studies (Formanack and Baier 2004).

We postulated that a MCT diet might have a positive impact on metabolic parameters and that this effect could be modulated by the FABP2 genotype. We expected a lower impact of genotype on the response to an MCT than to an LCT diet because FABP2 binds preferentially long-chain fatty acids (Richieri et al. 1994, 2000). This is supported by higher postprandial lipemia after olive or sunflower oil rather than butter (Higashi et al. 1997; Mekki et al. 2002). A diet–gene interaction for the FABP2 Thr54Ala polymorphism was shown for intervention with olive oil and butter, resulting in increased chylomicron cholesterol in T54 carriers only after olive oil (Dworatzek et al. 2004). This effect might have been induced by differences in the chain length or different in the saturation grade of the test fats, because both were changed between groups in this study.

In the presented study, fasting and postprandial glucose, insulin, HOMA and triacylglycerols did not change in either haplotype group during intervention (Table 3). In both haplotype groups, postprandial HDL increased during the intervention but only homozygous haplotype A carriers showed a significant increase after MCT diet, which was not seen after LCT diet. Up until now, an influence of FABP2 promoter variability on the postprandial triglyceride metabolism has only been described in combination with the FABP2 exon 2 polymorphism (A54T) (Helwig et al. 2007). The combination of the homozygosity of FABP2 promoter BB and the homozygosity of exon polymorphism (T54T) was associated with increased postprandial triacylglycerol levels. Therefore, we additionally evaluated the data of the subgroup with the genotypes FABP2 AA +A54A and FABP2 BB + T54T. In the total sample as well as in these subsets, we did not find differences in the effect of MCT/LCT diet on the metabolic parameters except HDL cholesterol.

There are different possible explanations for our findings. Compared to other MCT intervention studies, we administered a higher daily amount of MCT (44 g) compared to the LCT diet (40 g). This was to compensate for the lower energy density of MCT fat and was not accounted for in former studies (Eckel et al. 1992; Asakura et al. 2000; Van Wymelbeke et al. 2001). The significant positive effect of MCT fat on HDL cholesterol only in haplotype A subjects can be explained by a higher basal FABP2 promoter activity of these subjects (Helwig et al. 2007), which is probably associated with a higher binding capacity and oxidation of fatty acids.

In former reporter gene assays, the common FABP2 A haplotype showed a higher basal promoter activity but a lower responsiveness to PPARγ/RXR of FABP2 compared to the rare B haplotype (Helwig et al. 2007). Therefore, the amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the diet could contribute to an upregulation of FABP2 expression in haplotype B subjects and diminish the difference in haplotypes A and B subjects. Furthermore, we cannot exclude emerging positive effects of MCT after a longer dietary period.

In conclusion, with the exception of HDL cholesterol, the insulin and lipid metabolism of FABP2 promoter haplotype A and B subjects did not respond differently to administration of MCT diet even though the saturation grade was equal to that of the LCT diet.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- FA:

-

Free fatty acids

- FABP2:

-

Fatty-acid-binding protein-2

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- LCT:

-

Long-chain triacylglycerols

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- n.s.:

-

Not significant

- IGT:

-

Impaired glucose tolerance

- MCT:

-

Medium-chain triacylglycerols

- MCFA:

-

Medium-chain fatty acid

- MICK:

-

Metabolic Intervention Cohort Kiel

- OMTT:

-

Oral metabolic tolerance test

- OGTT:

-

Oral glucose tolerance test

- TG:

-

Triacylglycerols

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

References

Agren JJ, Valve R, Vidgren H, Laakso M, Uusitupa M (1998) Postprandial lipemic response is modified by the polymorphism at codon 54 of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18:1606–1610

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ (1998) Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 15:539–553

Asakura L, Lottenberg AM, Neves MQ, Nunes VS, Rocha JC, Passarelli M, Nakandakare ER, Quintao EC (2000) Dietary medium-chain triacylglycerol prevents the postprandial rise of plasma triacylglycerols but induces hypercholesterolemia in primary hypertriglyceridemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 71:701–705

Bach AC, Ingenbleek Y, Frey A (1996) The usefulness of dietary medium-chain triglycerides in body weight control: fact or fancy? J Lipid Res 37:708–726

Baier LJ, Sacchettini JC, Knowler WC, Eads J, Paolisso G, Tataranni PA, Mochizuki H, Bennett PH, Bogardus C, Prochazka M (1995) An amino acid substitution in the human intestinal fatty acid binding protein is associated with increased fatty acid binding, increased fat oxidation, and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 95:1281–1287

Ball MJ (1993) Parenteral nutrition in the critically ill: use of a medium chain triglyceride emulsion. Intensive Care Med 19:89–95

Binnert C, Pachiaudi C, Beylot M, Hans D, Vandermander J, Chantre P, Riou JP, Laville M (1998) Influence of human obesity on the metabolic fate of dietary long- and medium-chain triacylglycerols. Am J Clin Nutr 67:595–601

Chambers E, Godwin SL, Vecchio FA (2000) Cognitive strategies for reporting portion sizes using dietary recall procedures. J Am Diet Assoc 100:891–897

Damcott CM, Feingold E, Moffett SP, Barmada MM, Marshall JA, Hamman RF, Ferrell RE (2003) Variation in the FABP2 promoter alters transcriptional activity and is associated with body composition and plasma lipid levels. Hum Genet 112:610–616

Dworatzek PD, Hegele RA, Wolever TM (2004) Postprandial lipemia in subjects with the threonine 54 variant of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene is dependent on the type of fat ingested. Am J Clin Nutr 79:1110–1117

Eckel RH, Hanson AS, Chen AY, Berman JN, Yost TJ, Brass EP (1992) Dietary substitution of medium-chain triglycerides improves insulin-mediated glucose metabolism in NIDDM subjects. Diabetes 41:641–647

Formanack ML, Baier LJ (2004) Variation in the FABP2 promoter affects gene expression: implications for prior association studies. Diabetologia 47:349–351

Geschonke K, Klempt M, Lynch N, Schreiber S, Fenselau S, Schrezenmeir J (2002) Detection of a promoter polymorphism in the gene of intestinal fatty acid binding protein (I-FABP). Ann NY Acad Sci 967:548–553

Hampe J, Shaw SH, Saiz R, Leysens N, Lantermann A, Mascheretti S, Lynch NJ, MacPherson AJ, Bridger S, van Deventer S, Stokkers P, Morin P, Mirza MM, Forbes A, Lennard-Jones JE, Mathew CG, Curran ME, Schreiber S (1999) Linkage of inflammatory bowel disease to human chromosome 6p. Am J Hum Genet 65:1647–1655

Han JR, Deng B, Sun J, Chen CG, Corkey BE, Kirkland JL, Ma J, Guo W (2007) Effects of dietary medium-chain triglyceride on weight loss and insulin sensitivity in a group of moderately overweight free-living type 2 diabetic Chinese subjects. Metabolism 56:985–991

Hegele RA, Wolever TM, Story JA, Connelly PW, Jenkins DJ (1997) Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein variation associated with variation in the response of plasma lipoproteins to dietary fibre. Eur J Clin Invest 27:857–862

Helwig U, Rubin D, Klapper M, Li Y, Nothnagel M, Folsch UR, Doring F, Schreiber S, Schrezenmeir J (2007) The association of fatty acid-binding protein 2 A54T polymorphism with postprandial lipemia depends on promoter variability. Metabolism 56:723–731

Higashi K, Ishikawa T, Shige H, Tomiyasu K, Yoshida H, Ito T, Nakajima K, Yonemura A, Sawada S, Nakamura H (1997) Olive oil increases the magnitude of postprandial chylomicron remnants compared to milk fat and safflower oil. J Am Coll Nutr 16:429–434

Hill JO, Peters JC, Yang D, Sharp T, Kaler M, Abumrad NN, Greene HL (1989) Thermogenesis in humans during overfeeding with medium-chain triglycerides. Metabolism 38:641–648

Huang H, Starodub O, McIntosh A, Kier AB, Schroeder F (2002) Liver fatty acid-binding protein targets fatty acids to the nucleus. Real time confocal and multiphoton fluorescence imaging in living cells. J Biol Chem 277:29139–29151

Johnson RK, Driscoll P, Goran MI (1996) Comparison of multiple-pass 24-hour recall estimates of energy intake with total energy expenditure determined by the doubly labeled water method in young children. J Am Diet Assoc 96:1140–1144

Li Y, Fisher E, Klapper M, Boeing H, Pfeiffer A, Hampe J, Schreiber S, Burwinkel B, Schrezenmeir J, Doring F (2006) Association between functional FABP2 promoter haplotype and type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 38:300–307

Lowe JB, Sacchettini JC, Laposata M, McQuillan JJ, Gordon JI (1987) Expression of rat intestinal fatty acid-binding protein in Escherichia coli. Purification and comparison of ligand binding characteristics with that of Escherichia coli-derived rat liver fatty acid-binding protein. J Biol Chem 262:5931–5937

Marin C, Perez-Jimenez F, Gomez P, Delgado J, Paniagua JA, Lozano A, Cortes B, Jimenez-Gomez Y, Gomez MJ, Lopez-Miranda J (2005) The Ala54Thr polymorphism of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene is associated with a change in insulin sensitivity after a change in the type of dietary fat. Am J Clin Nutr 82:196–200

Marten B, Pfeuffer M, Schrezenmeir J (2006) Medium-chain triglycerides. Int Diary J 16:1374–1382

Mekki N, Charbonnier M, Borel P, Leonardi J, Juhel C, Portugal H, Lairon D (2002) Butter differs from olive oil and sunflower oil in its effects on postprandial lipemia and triacylglycerol-rich lipoproteins after single mixed meals in healthy young men. J Nutr 132:3642–3649

Mills GLLP, Weech PK (1989) A guidebook to lipoprotein technique. In: Burdon RH, van Knippenberg PH (eds) Laboratory techniques in biochemistry and molecular biology, vol 14. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Nosaka N, Maki H, Suzuki Y, Haruna H, Ohara A, Kasai M, Tsuji H, Aoyama T, Okazaki M, Igarashi O, Kondo K (2003) Effects of margarine containing medium-chain triacylglycerols on body fat reduction in humans. J Atheroscler Thromb 10:290–298

Oikari S, Ahtialansaari T, Huotari A, Kiehne K, Fölsch UR, Wolffram S, Jänne J, Alhonen L, Herzig KH (2008) Effect of medium- and long-chain fatty acid diets on PPAR and SREBP-1 expression and glucose homeostasis in ACBP-overexpressing transgenic rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf)194:57–65

Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA (1963) The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1:785–789

Richieri GV, Ogata RT, Kleinfeld AM (1994) Equilibrium constants for the binding of fatty acids with fatty acid-binding proteins from adipocyte, intestine, heart, and liver measured with the fluorescent probe ADIFAB. J Biol Chem 269:23918–23930

Richieri GV, Ogata RT, Zimmerman AW, Veerkamp JH, Kleinfeld AM (2000) Fatty acid binding proteins from different tissues show distinct patterns of fatty acid interactions. Biochemistry 39:7197–7204

Rubin D, Helwig U, Nothnagel M, Lemke N, Schreiber S, Folsch UR, Doring F, Schrezenmeir J (2008) Postprandial plasma adiponectin decreases after glucose and high fat meal and is independently associated with postprandial triacylglycerols but not with – 11388 promoter polymorphism. Br J Nutr 99:76–82

Rubin D, Helwig U, Nothnagel M, Folsch UR, Schreiber S, Schrezenmeir J (2010) Association of postprandial and fasting triglycerides with traits of the metabolic syndrome in the Metabolic Intervention Cohort Kiel. Eur J Endocrinol 162:719–727

Tholstrup T, Ehnholm C, Jauhiainen M, Petersen M, Hoy CE, Lund P, Sandstrom B (2004) Effects of medium-chain fatty acids and oleic acid on blood lipids, lipoproteins, glucose, insulin, and lipid transfer protein activities. Am J Clin Nutr 79:564–569

Van Wymelbeke V, Louis-Sylvestre J, Fantino M (2001) Substrate oxidation and control of food intake in men after a fat-substitute meal compared with meals supplemented with an isoenergetic load of carbohydrate, long-chain triacylglycerols, or medium-chain triacylglycerols. Am J Clin Nutr 74:620–630

Yonezawa T, Yonekura S, Sanosaka M, Hagino A, Katoh K, Obara Y (2004) Octanoate stimulates cytosolic triacylglycerol accumulation and CD36 mRNA expression but inhibits acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase activity in primary cultured bovine mammary epithelial cells. J Dairy Res 71:398–404

Acknowledgments

None of the authors had any financial or personal conflicts of interest. This work was financially supported by the BMBF Project “Fat and metabolism—gene variation, gene regulation and gene function” MN (0312823A/B). DR, UH, JS, MP and SD were responsible for the study design; DR, UH and DM were responsible for data collection; DR, SF, MN and AR were responsible for data analysis; and DR, MN, UF, FD, SS and JS were responsible for writing the manuscript. We thank A. Thoss, M. Hartelt, M. Gerull and S. Kaschner for excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rubin, D., Helwig, U., Pfeuffer, M. et al. The effect of FABP2 promoter haplotype on response to a diet with medium-chain triacylglycerols. Genes Nutr 7, 437–445 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-012-0280-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-012-0280-z