Abstract

We investigate the political determinants of liberalization in OECD network industries, performing a panel estimation over 30 years, through the largest and most updated sample available. Our results contrast with the traditional wisdom according to which right-wing governments do promote market-oriented policies more intensively than left-wing ones. Our findings reveal a neglected role of the so-called neoliberalism in promoting left-wing market-oriented policy. As a result, we claim that ideological cleavages ceased to act as determinants of the liberalization wave observed in network industries. This result is confirmed when controlling for the existing regulatory conditions that executives find when elected. Furthermore, we find that the country’s exposure to other countries’ policy initiatives acts as a positive stimulus for liberalization policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See the “Appendix” for a detailed description of the liberalization index that we used.

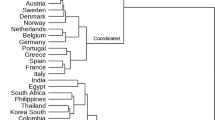

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States. Note, however, that in the estimation analysis, we drop from the sample the Czech Republic’s and Hungary’s observations referring to the years of communist dictatorship and those Slovakia’s observations that refer to the period before it was declared a sovereign state; Switzerland is removed from the final sample because of missing data on the main political characteristics of the government.

The OECD’s (2009) entry barriers indicator measures the legal market conditions, while it is not influenced by informal enforcement (see Conway and Nicoletti (2006)). This allows us to measure precisely the link between entry conditions and government’s actions, since the OECD’s liberalization scores explicitly refer to the individual years in which the policy interventions have been enacted.

Note that such transformation allows us to avoid further loss of degrees of freedom that could reduce the consistency of our estimates.

In both the fixed and random effects models, the latent dimension accounts for country and time effects, so that both time and spatial structures of the data are modeled. It is also worth noting that we consider a dependent variable (LiberalizationIntensity) which is obtained by first-differentiating variable measured in its absolute levels (Liberalization), the one-year-lagged first-differentiated variable then is included in the model as the autoregressive component; this strongly reduces possible temporal dependence problems.

Both the Potrafke’s Ideology index and the Armingeon et al.’s GovParty index provide a coding only for the following 23 countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States. The Armingeon et al.’s GovParty index does not provide a classification of the Italian government for the year 1995.

This refers to Arellano and Bond (1991) analysis showing that, in dynamic panel models, lag values of the dependent variable may be correlated with the unobserved country-specific effects. To overcome this problem, they propose a method-of-moments (GMM) estimator that is derived by first-differencing the panel model equation and by using moment conditions in which lags of the dependent variable and first-differences of the exogenous variables are instruments for the first-differenced equation.

References

Alesina A (1988) Macroeconomics and politics. In: Fisher S (ed) NBER macroeconomics annual. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 17–52

Alesina A, Giavazzi F (2007) Il Liberismo è di Sinistra. Il Saggiatore, Milano

Alesina A, Rosenthal H (1995) Partisan politics, divided government, and the economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Arin K, Ulubasoglu M (2009) Leviathan resists: the endogenous relationship between privatization and firm performance. Public Choice 140(1):185–204

Armingeon K, Engler S, Potolidis P, Gerber M, Leimgruber P (2010) Comparative political data set 1960–2008. Institute of Political Science, University of Berne

Armstrong M, Sappington D (2006) Regulation, competition and liberalization. J Econ Lit 32(2):353–380

Besley T (2007) Electoral strategy and economic policy. Unpublished manuscript

Besley T, Case A (2003) Political institutions and policy choices: evidence from the United States? J Econ Lit 41(1):7–73

Besley T, Persson T, Sturn DM (2010) Political competition, policy and growth: theory and evidence from the United States. Rev Econ Stud (forthcoming)

Biais B, Perotti E (2002) Machiavellian privatization. Am Econ Rev 92(1):240–258

Biørnskov C, Potrafke N (2009) Political ideology and economic freedom across Canadian provinces. Université Libre de Bruxelles

Blanchard O, Giavazzi F (2003) The macroeconomic effects of regulation and deregulation of goods and labor markets. Q J Econ 118(3):879–907

Boix C (1997) Political parties and the supply side of the economy: the provision of physical and human capital in advanced economies, 1960–90. Am J Polit Sci 41(3):814–845

Bortolotti B, Pinotti P (2008) Delayed privatization. Public Choice 136(3):331–351

Butler T, Savage M (1995) Social change and the middle class. UCL Press, London

Castaldo A, Nicita A (2007) Essential facility access in Europe: building a test for antitrust policy. Rev Law Econ 3(1). doi:10.2202/1555-5879.1078

Conway P, Nicoletti G (2006) Product market regulation in the non-manufacturing sectors of OECD countries: measurement and highlights. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 530

Cukierman A, Tommasi M (1998) When does it take a Nixon to go to China? Am Econ Rev 88(1):180–197

Dinc S, Gupta N (2007) The decision to privatize: the role of political competition and patronage. MIT, unpublished manuscript

Dobbin F, Simmons B, Garrett G (2007) The global diffusion of public policies: social construction, coercion, competition, or learning? Annu Rev Sociol 33:449–472

Duso T (2002) On politics of the regulatory reform: evidence from the OECD countries. WZB Discussion Paper No.FS-IV-02-07

Duso T, Seldeslachts J (2009) The political economy of mobile telecommunications liberalization: evidence from OECD countries. J Comp Econ 38(2):199–216

Dutt P, Mitra D (2005) Political ideology and endogenous trade policy: an empirical investigation. Rev Econ Stat 87(1):59–72

Esping-Andersen G (ed) (1993) Changing classes: stratification and mobility in post-industrial societies. Sage, London

Garrett G (1998) Global markets and national politics: collision course or virtuous cycle? Int Organ 52(4):787–824

Giuliano P, Scalise D (2009) The political economy of agricultural market reforms in developing countries. BE J Econ Anal 9(1). doi:10.2202/1935-1682.2023

Guriev S, Megginson W (2007) Privatization: what have we learned? In: Bourguignon F, Pleskovic B (eds) Beyond transition, proceedings of the 18th ABCDE. World Bank, Washington

Høj J, Galasso V, Nicoletti G, Dang T (2006) The political economy of structural reform: empirical evidence from OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 501, OECD, Economics Department

Hout M, Brooks C, Manza J (1995) The democratic class struggle in the United States. Am Sociol Rev 60:805–828

Krause S, Méndez F (2005) Policy makers’ preferences, party ideology, and the political business Cycle. South Econ J 71(4):752–767

Kriesi H (1989) New social movements and the new class in the Netherlands. Am J Sociol 94(5):1078–1116

Levy B, Spiller P (1996) A framework for resolving the regulatory problem. In: Levy B, Spiller P (eds) Regulations, institutions and commitment: comparative studies in regulation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 121–144

Li W, Xu LC (2002) The political economy of privatization and competition: cross-country evidence from the telecommunications sector. J Comp Econ 30(3):439–462

Manza J, Brooks C (1999) Social cleavages and political change: voter alignments and US party coalitions. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Meggison WL, Netter JM (2001) From state to market: a survey of empirical studies on privatization. J Econ Lit 39(2):321–389

Newbery DM (1997) Privatization and liberalization of network utilities. Eur Econ Rev 41(3–5):357–383

Newbery DM (2002) Problems of liberalising the electricity industry. Eur Econ Rev 46(4–5):919–927

OECD (2008) Indicators on employment protection. Available at http://www.oecd.org, Dec 2009

OECD (2009) ETCR indicators. Available at http://www.oecd.org, Feb 2010

Perotti E (1995) Credible privatization. Am Econ Rev 85(4):847–859

Persson T (2002) Do political institutions shape economic policy? Econometrica 70(3):883–905

Persson T, Tabellini G (2000) Political economics: explaining economic policy. MIT Press, Cambridge

Pitlik H (2007) A race to liberalization? Diffusion of economic policy reform among OECD economies. Public Choice 132:159–178

Potrafke N (2010) Does government ideology influence deregulation of product markets? Empirical evidence from OECD countries. Public Choice 143(1–2):135–155

Rodrik D (2003) Growth strategies. Technical Report Working Paper 10050, NBER, Cambridge

Ross F (2000) Beyond left and right: the new partisan politics of welfare. Gov Int J Policy Adm 13(2):155–183

Roy RK, Denzau AT, Willett TD (eds) (2006) Neoliberalism: national and regional experiments with global ideas. Routledge, New York

Schneider V, Häge FM (2008) Europeanization and the retreat of the state. J Eur Public Policy 15(1):1–19

Schneider V, Fink S, Tenbucken M (2005) Buying out the state: a comparative perspective on the privatization of infrastructures. Comp Polit Stud 38(6):704–727

Simmons B, Elkins Z (2004) The globalization of liberalization: policy diffusion in the international political economy. Am Polit Sci Rev 98(1):171–189

Steger MB, Roy RK (2010) Neoliberalism: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, New York

Vickers J, Yarrow G (1991) Economic perspectives on privatization. J Econ Persp 5(2):111–132

Wooldridge JM (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. The MIT Press, Cambridge

World Bank (2008) World development indicators. Washington

World Bank (2009) Database of political institutions. Available at http://econ.worldbank.org, Feb 2010

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank, for helpful comments and criticism, Carlo Cambini, Xavier Fernàndez i Marìn, Philippe Martin, Emanuela Michetti, Fabio Padovano, Pier Luigi Parcu, Niklas Potrafke, V. Visco Comandini, Stefan Voigt, and two anonymous referees. We would also thank participants to the 2010 ISNIE conference, in particular Christian Bjørnskov and Norman Schofield, and to the 2010 EALE conference. Usual disclaimers apply. We kindly acknowledge financial support by REFGOV—Institutional Frames for Markets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Liberalization index’s description

Appendix: Liberalization index’s description

We measure liberalization policy by subtracting the OECD’s (2009) entry barriers index from its maximum value (let us call this variable Liberalization) and then calculate the intensity of liberalization interventions (LiberalizationIntensity) by looking at the one-year differences of Liberalization. The OECD’s (2009) entry barriers index is calculated by OECD as the simple average of seven sectoral indicators that, in turn, measure the strictness of the legal conditions of entry in the seven non-manufacturing sectors. The OECD’s (2009) sectoral indicators focus on sector-specific aspects of entry regulation, as follows. Passenger air transport: the focus is on open skies agreements with the USA, regional agreements, and restriction on the number of domestic airlines allowed to operate on domestic routes. Telecom: the focus is on the legal conditions of entry into the trunk telephony market, the international market, and the mobile market. Electricity: the focus is on the conditions of third-party access to the electricity transmission grid and on the conditions of the competition in the market for electricity. Gas: the focus is on the conditions of third-party access to the gas transmission grid, on the share of the retail market open to consumer choice, and on the existence of any regulation that restricts the number of competitors allowed to operate in the market. Post: the focus is on the existence of any regulation that restricts the number of competitors allowed to operate in the national market of basic letter services, basic parcel services, and courier activities. Rail: the focus is on the legal conditions of entry into the passenger and the freight transport rail markets. Road: the focus is on the criteria considered in decisions on entry of new operators.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Belloc, F., Nicita, A. The political determinants of liberalization: do ideological cleavages still matter?. Int Rev Econ 58, 121–145 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-011-0124-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-011-0124-y