Abstract

Background

When people think that their efforts will fail to achieve positive outcomes, they sometimes give up their efforts after control, which can have negative health consequences.

Purpose

Problematic orientations of this type, such as pessimism, helplessness, or fatalism, seem likely to be associated with a cognitive mindset marked by higher levels of accessibility for failure words or concepts. Thus, the purpose of the present research was to determine whether there are individual differences in the frequency with which people think about failure, which in turn are likely to impact health across large spans of time.

Methods

Following self-regulatory theories of health and the learned helplessness tradition, two archival studies (total n = 197) scored texts (books or speeches) for their use of failure words, a category within the Harvard IV dictionary of the General Inquirer.

Results

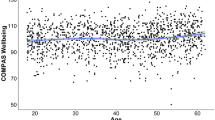

People who used failure words more frequently exhibited shorter subsequent life spans, and this relationship remained significant when controlling for birth year. Furthermore, study 2 implicated behavioral factors. For example, the failure/longevity relationship was numerically stronger among people whose causes of death appeared to be preventable rather than non-preventable.

Conclusions

These results significantly extend our knowledge of the personality/longevity relationship while highlighting the value of individual differences in word usage as predictors of health and mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Skinner EA. A guide to constructs of control. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996; 71: 549–570.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman; 1997.

Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

Maier SF, Seligman M.E. Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1976; 105: 3–46.

Evans GW, Stecker R. Motivational consequences of environmental stress. J Environ Psychol. 2004; 24: 143–165.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004; 31: 143–164.

Schwarzer R. Social-cognitive factors in changing health-related behaviors. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001; 10: 47–51.

Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Bridging the intention-behaviour gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychol Health. 2005; 20: 143–160.

Rasmussen HN, Wrosch C, Scheier MF, carver CS (2006). Self-regulation processes and health: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. J Pers. 2006; 74: 1721–1747.

Mokdad A, Marks J, Stroup D, Gerberding J. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004; 291:1238–1245.

Jacelon CS. Theoretical perspectives of perceived control in older adults: A selective review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2007; 59: 1–10.

Peterson C, Seligman ME. Explanatory style and illness. J Pers. 1987; 55: 237–265.

Smith TW. Personality as risk and resilience in physical health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2006; 15: 227–231.

Pervin LA. A critical analysis of current trait theory. Psychol Inq. 1994; 5: 103–113.

Peterson C, Stunkard, AJ. Personal control and health promotion. Soc Sci Med. 1989; 28: 819–828.

Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, Niederhoffer KG. Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003; 54: 547–577.

Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J Lang Soc Psychol. 2010; 29: 24–54.

Stirman SW, Pennebaker JW. Word use in the poetry of suicidal and nonsuicidal poets. Psychosom Med. 2001; 63: 517–522.

Pressman SD, Cohen S. Use of social words in autobiographies and longevity. Psychosom Med. 2007; 69: 262–269.

Carver CS, Scheier MF. Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014; 18: 293–299.

Peterson, C. Learned helplessness and health psychology. Health Psychol. 1982; 1: 153–168.

Shen L, Condit CM, Wright L. The psychometric property and validation of a fatalism scale. Psychol Health. 2009; 24: 597–613.

Armor DA, Taylor SE. The effects of mindset on behavior: Self-regulation in deliberative and implemental frames of mind. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2003; 29: 86–95.

Heckhausen H. Fear of failure as a self-reinforcing motive system. In: Sarason I, Spielberger C, ed. Stress and anxiety. Washington, DC: Hemisphere; 1975: 117–128.

McClelland DC. Human motivation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

Ogilvie DM, Stone PJ, Kelly EF. Computer aided content analysis. In: Smith RB, Manning PK, ed. A handbook of social science methods. Cambridge, MA: Balinger; 1982: 219–246.

Higgins ET. Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, ed. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press; 1996: 133–168.

Robinson MD, Vargas PT, Tamir M, & Solberg E. Using and being used by categories: The case of negative evaluations and daily well-being. Psychol Sci. 2004; 15: 521–526.

Bargh JA, Chartrand TL. The mind in the middle: A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, ed. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000: 253–285.

Williams DM. Outcome expectancy and self-efficacy: Theoretical implications and unresolved contradiction. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2010; 14: 417–425.

Schwarzer R. Self-regulatory processes in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors: The role of optimism, goals, and threats. J Health Psychol. 1999; 4: 115–127.

Smith TW, MacKenzie J. Personality and risk of physical illness. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006; 2: 435–467.

Lin EH, Peterson C. Pessimistic explanatory style and response to illness. Behav Res Ther. 1990; 28: 243–248.

Mehl MR. Quantitative text analysis. In: Eid M, Diener E, ed. Handbook of multimethod measurement in psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006: 141–156.

Stone PJ. Thematic text analysis: New agendas for analyzing text content. In: Roberts CW, ed. Text analysis for the social sciences: Methods for drawing statistical inferences from texts and transcripts. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997: 35–54.

Stone PJ, Dunphy DC, Smith MS, Ogilvie DM. The general inquirer: A computer approach to content analysis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1966.

Kelly EF, Stone PJ. Computer recognition of English word senses. Amsterdam, Netherlands: North Holland; 1975.

Zuell C, Weber RP, Mohler PP. Computer-assisted text analysis for the social sciences: The General Inquirer III. Mannheim, Germany: Center for Surveys, Methods, and Analysis (ZUMA); 1989.

Rosenberg SD, Schnurr PP, & Oxman TE. Content analysis: A comparison of manual and computerized systems. J Pers Assess. 1990; 54: 298–310.

Pennebaker JW, Chung CK, Ireland M, Gonzales AL Booth RJ. The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2007. Austin, TX: www.LIWC.net; 2007.

Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991.

Hayflick L. How and why we age. New York, NY: Ballantine Books; 1996.

Winter DG. Measuring the motives of political actors at a distance. In: Post JM, ed. The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders: With Profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton (pp. 153–177). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press; 2005: 153–177.

Livingstone RM. Models for understanding collective intelligence on Wikipedia. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2016; 34: 497–508.

Messner M, DiStaso MW. Wikipedia versus encyclopedia Britannica: A longitudinal analysis to identify the impact of social media on the standards of knowledge. Mass Commun Soc. 2013; 16: 465–486.

Schroeder R, Taylor L. Big data and Wikipedia research: Social science knowledge across disciplinary divides. Information, Communication & Society. 2015; 18:1039–1056.

Pennebaker JW. Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychol Sci. 1997; 8: 162–166.

Pennebaker JW, Graybeal A. Patterns of natural language use: Disclosure, personality, and social integration. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001; 10: 90–93.

Robinson MD, Wilkowski BM. Personality processes and processes as personality: A cognitive perspective. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, ed. APA handbook of personality and social psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015: 129–145.

Pennebaker JW. Listening to what people say—The value of narrative and computational linguistics in health psychology. Psychol health. 2007; 22: 631–635.

Cervone D. Bottom-up explanation in personality psychology: The case of cross-situational coherence. In: Cervone D, Shoda Y, ed. The coherence of personality: Social-cognitive bases of consistency, variability, and organization. New York: Guilford Press; 1999: 303–341.

Eysenck H. Dimensions of personality. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1998.

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010; 30: 879–889.

Kruglanski A, Shah J, Fishbach A, Friedman R, Chun W, Sleeth-Keppler D. A theory of goal systems. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 34. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press; 2002: 331–378.

Weber RP. Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990.

Fetterman AK, Boyd RL,Robinson MD. Power versus affiliation in political ideology: Robust linguistic evidence for distinct motivation-related signatures. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2015; 41: 1195–1206.

Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim, C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2009; 10: 434–445.

Bogg T, Roberts BW. The case for conscientiousness: Evidence and implications for a personality trait marker of health and longevity. Ann Behav Med. 2013; 45: 278–288.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Ian B. Penzel, Michelle R. Persich, Ryan L. Boyd, and Michael D. Robinson declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

About this article

Cite this article

Penzel, I.B., Persich, M.R., Boyd, R.L. et al. Linguistic Evidence for the Failure Mindset as a Predictor of Life Span Longevity. ann. behav. med. 51, 348–355 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9857-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9857-x