Abstract

While education communities have well defined commitments to protect their learners from oppressive instructional materials, discourses of science education are often left unexamined. This analysis/critique employs queer theory as a perspective to look at how one widely used textbook in Ontario schools conceptualizes notions of gender and sexuality. Results indicate the use of discourses that promote exclusively heteronormative constructions of sexuality along with sex/gender binaries. Challenging such oppressive misconceptions of sex/gender and sexuality is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A good example of this outside of the context of this paper can be found in Lovelock’s (2001) Homage to Gaia: The Life of an Independent Scientist. Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis was initially completely rejected by leading biologists because it could not be easily subsumed by evolution through natural selection.

It is interesting to read Birke’s (1994, p. 123) take on the seminal experiment where hormonal injections prompted male rats to prostrate themselves and female rats to mount; thereby providing the opportunity to infer that homosexuality is linked to hormones. Birke astutely notes that the bodies of the ‘deviant’ male rats that prostrate become labeled as homosexual while the bodies of the ‘normal’ male rats who ‘properly’ mount are not. Similarly female rats that are mounted by ‘deviant’ mounting females are also not labeled homosexual. Thus imposed onto nature are cultural traditions that seek to label organisms that fall outside of expected norms as abhorrent.

References

Apple, M. (1990). The text and cultural politics. Journal of Educational Thought, 24, 17–33.

Bagemihl, B. (1999). Biological exuberance: Animal homosexuality and natural diversity. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Birke, L. (1994). Feminism, animals and science: The naming of the shrew. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Birke, L. (2000). Feminism and the biological body. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Britzman, D. (1998). Lost subjects, contested objects: Toward a psychoanalytic inquiry of learning. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of sex. New York: Routledge.

Carter, L. (2007). Sociocultural influences on science education: Innovation for contemporary times. Science Education, 92, 165–181.

Cavanagh, S., & Sykes, H. (2006). Transexual bodies at the olympics: The international olympic committee’s policy on transsexual athletes at the 2004 Athens summer games. Body Society, 12, 75–102.

Connell, B. (2009). Gender. Syndey: Polity Press.

Connelly, M., He, F., & Phillion, J. (2008). The sage handbook of curriculum and instruction. London: Sage Publications.

Cowper’s Gland. (2008). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 4, 2009 from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/84039/bulbourethral-gland.

Duggan, L. (1995). The discipline problem: Queer theory meets lesbian and gay history. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 2, 179–191.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (1992). Myths of gender: Biological theories about women and men ((2 Rev Sub ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2000). Sexing the body. New York: Basic Books.

Felski, R. (1998). Introduction. In L. Bland & L. Doan (Eds.), Sexology in culture: Labelling bodies and desires (pp. 116–131). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Fifield, S. (2001, January). Identity, knowledge, and heteronormativity in science teacher education. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Education of Teachers in Science, Costa Mesa, CA.

Foucault, M. (1998). History of sexuality (Vol. 1). New York: Penguin.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Haraway, D. (1997). Modest-witness@second-millenium. FemaleMan-meets-oncomouse: Feminism and technoscience. New York: Routledge.

Harding, S. (1993). The science question in feminism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Harding, S. (1998). Is science multicultural? Postcolonialism, feminism & epistemologies: Postcolonialisms, feminisms, and epistemologies. Bloomington, ID: Indiana University Press.

Hird, M. (2004). Sex, gender and science. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Irigaray, L. (1993). An ethics of sexual difference. New York: Continuum.

Jagose, A. (1996). Queer theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press.

Kinsey, A., Pomeroy, W., & Martin, C. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Kuhn, T. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kumashiro, K. (2000). Toward a theory of anti-oprresive education. Review of Educational Research, 70, 25–53.

Letts, W. J. (1999). How to make “boys” and “girls” in the classroom: The heteronormative nature of elementary-school science. In W. J. Letts & J. Sears (Eds.), Queering elementary education: Advancing the dialogue about sexualities and schooling (pp. 97–110). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lovelock, J. (2001). Homage to Gaia: The life of an independent scientist (New ed.). New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

Mccaskell, T. (2005). Race to equity: Disrupting educational inequality. Toronto: Between The Lines.

McGraw Hill Ryerson. (2002). Biology 12. Toronto: McGraw Hill Ryerson.

Merton, K. (1947). Science, technology & society in seventeenth-century England. New York: Howard Fertig.

Minton, H. (1997). Queer theory: Historical roots and implications for psychology. Theory & Psychology, 7, 337–353.

Moallem, J. (2010). Can animals be gay? New York Times. Retrieved April 18 from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/04/magazine/04animalst.html?pagewanted=1&ref=magazine.

Namaste, V. (2000). Invisible lives: The erasure of transsexual and transgendered people. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Nehm, H., & Young, R. (2008). “Sex Hormones” in secondary school biology textbooks. Science & Education, 17, 1175–1190.

Nelson, C. (1999). Sexual identities in ESL: Queer theory and classroom inquiry. Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Quarterly, 33, 371–391.

Nieto, M. (2008). Anatomy is destiny, except sometimes. The Gay and Lesbian Review World Wide, 15(6), 21–23.

Oudshoorn, N. (1994). Beyond the natural body: An archaeology of sex hormones. New York: Routledge.

Penn, D. (1995). Queer: Theorizing politics and history. Radical History Review, 62, 24–42.

Prosser, J. (1998). Transsexuals and transsexologists. In L. Bland & L. Doan (Eds.), Sexology in culture: Labelling bodies and desires (pp. 116–131). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Salvio, P. (2009). Uncanny exposures: A study of the wartime photojournalism of Lee Miller. Curriculum Inquiry, 39, 521–536.

Sartre, J.-P. (1964). Saint Genet, actor and martyr. New York: New American Library.

Schiebinger, L. (1991). The mind has no sex? Women in the origins of modern science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sears, J. (1999). Teaching queerly: Some elementary propositions. In W. J. Letts & J. Sears (Eds.), Queering elementary education: Advancing the dialogue about sexualities and schooling (pp. 3–14). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Sears, A. (2003). Retooling the mind factory: Education in lean state. Aurora, ON: Garamond Press.

Seitler, D. (2004). Queer physiognomies: Or, how many ways can we do the history of sexuality? Criticism, 46, 71–102.

Sleeter, C., & Grant, C. (1999). Making choices for multicultural education: Five approaches to race, class, and gender (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Snyder, L., & Broadway, S. (2004). Queering high school biology textbooks. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41, 617–636.

Somerville, S. (1994). Queering the color line: Race and the invention of homosexuality in American culture (Series Q). London: Duke University Press.

Spanier, B. (1995). Im/partial science: Gender ideology in molecular biology (race, gender, and science). Bloomington, ID: Indiana University Press.

Sumara, D., & Davis, B. (1999). Interrupting heteronormativity: Toward a queer curriculum theory. Curriculum Inquiry, 29, 191–208.

Temple, J. (2005). “People who are different from you”: Heterosexism in Quebec high school textbooks. Canadian Journal of Education, 28, 271–294.

Toronto District School Board. (2000). Equity foundation statement and commitments to equity policy implementation. Retrieved November 5, 2009 from http://www.tdsb.on.ca/_site/ViewItem.asp?siteid=15&menuid=7098&pageid=6194.

Wade, N. (2008). Taking a cue from ants on evolution of humans. New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2009 from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/15/science/15wils.html.

Weeks, J. (1993). Introduction to guy Hocquengham’s: Homosexual desire (pp. 49–55). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Weinstein, M., & Broda, M. (2009). Resuscitating the critical in the biological grotesque: Blood, guts, biomachismo in science/education and human guinea pig discourse. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 4, 761–780.

Wilson, E. O. (1999). Consilience: The unity of knowledge. New York: Vintage.

Wong, D. (2001). Perspectives on learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38, 279–281.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

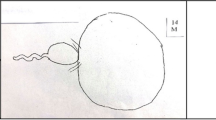

The only other picture in the entire text depicting an intimate relationship that could be assumed to be sexual is shown below. Intimacy was assumed because of the arm around the woman’s waste.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bazzul, J., Sykes, H. The secret identity of a biology textbook: straight and naturally sexed. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 6, 265–286 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-010-9297-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-010-9297-z