Abstract

Few studies have been performed on the importance of nutrient availability for plant productivity at <200 mm annual precipitation and available meta-analyses have produced contradicting results. Here, we present data from a 3-year experiment on the effects of NPK-fertilisation under ambient precipitation in dry Central Asian steppes. The study site had an annual mean precipitation of ca. 160 mm and represented an intensively grazed montane desert steppe. One year of NPK-fertilisation at levels equivalent to 10 and 20 gN/m2 (100 and 200 kg/ha) increased above-ground mean standing crop in a moist year to 1130 and 1490 kg dry mass/ha, respectively, compared to the 615 kg/ha from the control. The absolute increase was smaller in subsequent drier years, but the crop again more than doubled under fertilisation. The effects were most pronounced for the main fodder plants Agropyron cristatum and Allium polyrrhizum, which benefited from fertilisation more than other less palatable species. Both species also showed increased levels of foliar N. Fertilisation enhanced flowering activity on the community level, and soil analyses revealed that nutrients accumulate in the soil. Effects are therefore expected to be long lasting. Our results imply that nutrient shortage may co-limit plant growth at well below 200 mm annual precipitation. Considering that predominantly nomadic land use is known to result in nutrient withdrawal, our data raise concerns of a largely unnoticed potential pathway to pasture degradation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Availability of soil nitrogen and phosphorus is among the most important and widespread constraints for plant productivity (Elser et al. 2007; LeBauer and Treseder 2008). Evidence is less clear for drylands, which cover >30% of the terrestrial land surface (White et al. 2000). The relative importance of water versus nutrient limitation may change along the precipitation gradient (Breman and De Wit 1983), and a recent meta-analysis by Xia and Wan (2008) inferred that ecosystem productivity shows less pronounced responses to nitrogen addition under dry conditions. This is in contrast to other reviews that describe strong responses even in dry regions (Hooper and Johnson 1999; LeBauer and Treseder 2008). Recent studies from a number of drylands also suggest that nitrogen and phosphorus (less commonly assessed) may co-limit plant growth at well below 300 mm mean annual precipitation (Harpole et al. 2007; James et al. 2005). However, general inferences suffer from the lack of studies conducted under very low precipitation levels (<200 mm).

Data for Central Asia, with >4 Mio km2 of dry rangelands, are particularly scarce. As a consequence, nutrient limitations can hardly be considered in regional climate change models (Christensen et al. 2004; Zheng et al. 2006). Nutrient limitation may increase as a consequence of local land use, which is still based on nomadic pastoralism, especially in Mongolia. Transect studies along grazing gradients have provided evidence for livestock-mediated translocation of nitrogen and phosphorus towards wells or herders’ camps (Fernandez-Gimenez and Allen-Diaz 2001; Holst et al. 2007; Knopf et al. 2005; Stumpp et al. 2005). The withdrawal of nutrients from the surrounding steppes is aggravated by the practice of dung collection, which is still the main source of domestic fuel for Mongolian herders. This leads to concerns about deteriorating rangeland health and declining productivity. Along with effects on productivity, plant community composition may also be sensitive to shifts in nutrient availability. Observational studies found that the abundance and biomass productivity of palatable plants differ with nitrogen and phosphorus contents of the soils (Breymeyer and Klimek 1983; Weiner et al. 1982; Wesche et al. 2007; Wesche et al. accepted).

Among the few available experiments on nutrient limitation in dry Central Asia is a study by Slemnev et al. (2004), who applied nitrogen fertiliser in dry Stipa gobica steppes and found an increase in productivity. In this case, plots received additional irrigation. Fertilisation effects were tested in northern Chinese grasslands which receive >300 mm rain (e.g. Liu et al. 2007a; Pan et al. 2005), and Xiao et al. (2007) inferred nutrient limitation from a litter addition experiment. In an ongoing study, Kinugasa et al. (2008) applied low levels of nitrogen in Central Mongolia, but no significant effects were observed. We thus performed a replicated fertilisation experiment under ambient precipitation levels of <200 mm on the desert steppes of southern Mongolia. This study represents a rather general approach, because hardly any reference data were available on the main limiting elements or on appropriate levels of fertilisation. We used compound fertiliser with NPK and micronutrients. Nitrogen and phosphorus were thus jointly applied, as they were indeed found to be co-limiting in most of the globe’s biomes (Elser et al. 2007). Available Central Asian data indicate high N/P ratios in plant tissues, which may be indicative of phosphorus limitation (Güsewell 2004; He et al. 2008). Soil potassium levels in contrast are generally high at the study site and unlikely to constrain plant growth (Wesche et al. 2007). Annual variability of precipitation is high in southern Mongolia, and this strongly affects biomass productivity (Munkhtsetseg et al. 2007). Plant reproduction in southern Mongolia is also dependant on water availability (Ronnenberg et al. 2008). Hence, experiments on plant performance and biomass productivity under ambient conditions should cover several years to assess whether results are representative.

Specifically, we asked the following questions: (1) Are soil nutrient contents positively affected by NPK-fertilisation? (2) Does fertilisation affect plant community composition? Which species show the strongest response? (3) Does above-ground plant growth and flowering activity benefit from fertilisation? Can effects be observed over years with different precipitation levels? (4) Is plant nutrient content also influenced by nutrient availability?

Methods

Study area

The study was performed in the Gobi Gurvan Saykhan National Park in southern Mongolia, which is almost completely subjected to traditional land use by nomadic pastoralists despite its protection status (Bedunah and Schmidt 2004). Precipitation falls almost exclusively in summer, and mountains that cover around 30% of the park’s surface receive more precipitation than the lowlands, resulting in a vertical zonation of vegetation belts (Wesche et al. 2005). The interannual variation is pronounced (coefficient of variation >30%, Retzer 2004), and this is also indicated by short-term measurements at our study site (Table 1).

The study site is located on the upper pediments of the Dund Saykhan (43°36.949′N, 103°46.450′E, 2300 m a.s.l.). Its montane desert steppes are mainly constituted by Agropyron cristatum, Allium polyrrhizum, Artemisia frigida, Stipa krylovii and S. gobica. The site represents a semi-arid environment, and soil water movement is largely directed upwards, so cations tend to accumulate in the topsoil, which is shown by relatively high pH-values and high levels of calcium (Table 2).

Fieldwork

A transect study from the study region revealed that topsoils around permanently used water sources (wells) showed considerably higher concentrations of soil nitrogen and phosphorus than normal steppe grasslands 750–1500 m away (Stumpp et al. 2005). Mean total topsoil (upper 10 cm) N concentrations around the wells were 3.7 g/kg ± 0.4 s.e. at the 50 m piosphere and only 2.6 g/kg ± 0.5 s.e. at 750 m distance, while figures for mean lactate-exchangeable P were 0.081 g/kg ± 0.008 s.e. and 0.042 ± 0.007 g/kg, respectively. At a given mean soil bulk density of 1.4 g/cm3 (Ronnenberg unpubl.), these figures translate to average levels of ca. 160 g/m2 of Ntotal, and an equivalent of ca. 5.3 g/m2 of exchangeable P in the topsoil that had been translocated by livestock. We opted for relatively high levels of fertilisation at 10 g/m² and 20 g/m² of N (3.3 and 6.6 g/m² of P) per year, which is comparable with levels applied in a number of studies in dry regions (Gutierrez et al. 1988; Liu et al. 2007b; Pan et al. 2005; Paschke et al. 2000). The NP ratio of the fertiliser was thus narrower than the presumed NP ratio of the translocated nutrients, but because we had no data on plant exchangeable N along the transects, data are not directly comparable.

We used NPK fertiliser (FLORY 2, PLANTA Germany) with the following composition: 8.5% Nitrate-N; 6.5% Ammonia-N; 5% Phosphate-P; 25% Potassium (K2O); 2% Magnesium (MgO); and some micro elements (B, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Zn). We added fertiliser in two applications in July and August in each year of the study. Fertiliser was dissolved in water equivalent to 2 × 3 l/m². The same amount of water was added to the control, and subplots were separated widely enough to prevent roots taking nutrients from an adjacent treatment (>3 m). The experiment was conducted over several years (2003–2006) to capture the huge climatic variability in the system (Table 1) and to assess whether nutrients accumulate in the soil. The growing season in 2004 was relatively moist, the summer of 2005 was initially dry, but rains in July and August were comparable to those of 2004. 2006 was again initially very dry, but heavy rains commenced in late July.

The experiment was conducted away from wells and laid out in blocks to account for heterogeneity in the soil matrix. We randomly selected nine blocks and allocated three subplots per block in August 2003. Over each subplot, we placed a cage of fine meshed wire to protect biomass from consumption by livestock or small mammals (herbivory by insects was unimportant in the years of study). Cages were 0.5 m² in size, which had proven to be sufficient in previous studies (Wesche et al. 2007). In each cage, 0.2 m² was sampled in July and August 2004 (n = 9 blocks with 3 subplots each), subplots were fertilised afterwards. In 2004, we also established two further subplots per block, which were then fertilised for the first time (10 and 20 gN/m²) and later treated in the same way as those from 2003. Thus, in 2005 and 2006, the experiment involved five treatments (n = 9 × 5). We recorded a list of all plant species plus cover estimates and the respective number of inflorescences. Biomass as the standard variable used in most desertification assessments (Veron et al. 2006) was clipped 2 mm above ground, air-dried and later dried at 105°C in the lab. We distinguished between the main groups of Allium spp., Agropyron cristatum, Stipa spp., Artemisia frigida and the rest. Topsoil samples (depth 3–7 cm, mixed from three samples) were collected in August 2004 and August 2005, and the samples were likewise air-dried in the field. Conditions in the topsoil are most relevant for plant growth as roots of the dominant hemicryptophytes in the area are concentrated in the upper 10 cm of the soil (Borisova and Popova 1985; Kutschera et al. 1997).

Chemical analysis

Soil analysis concentrated on the manipulated nutrients, but other key variables were additionally measured. Organic carbon and nitrogen were analysed with a CN-Analyser (Vario EL, ELEMENTAR, Germany); total carbon figures were corrected for carbonate-borne C measured with a Scheibler instrument using HCl (10%). Available phosphate was extracted with Ca-Lactate at pH 3.6, stained with Ammonium-Molybdate and measured with a photometer (NANODROP, USA). Total soil cations were analysed after hot digestion with conc. HNO3; exchangeable cations were extracted by slow percolation with BaCl2 solution (0.1 mol/l). Ca and Mg were determined with Atomic Absorption Spectrometry and K with flame spectrometry (Flame AAS Vario EL, Analytik Jena, Germany). Soil pH and conductivity (20 g dry fine soil, 50 ml H2O) were measured with a standard probe (SenTix 21, WTW, Germany). All data refer to dry (105°C) fine soil (<2 mm). Plant tissues were only analysed for samples from 2004 (July and August harvests). Plant C and N were analysed with the same CN-Analyser, P and K were determined as described before, after hot digestion with HNO3.

Data analysis

Repeated samples can be analysed with Repeated Measures ANOVA, but in our case experimental designs differed among years. Moreover, temporal trends such as successions were not the main focus of our study, so we calculated ANOVAs separately for each year; significance values were then Bonferroni corrected across years for a given dependent variable (see Underwood 1997). Measurements from the same plot within a given year were, however, assessed with Repeated Measures ANOVAs (i.e. species’ biomass, plant nutrient contents). Homogeneity of variances was tested with a Levene test, and post hoc comparisons were performed with Tukey’s test (Sokal and Rohlf 1995). Percentages were arcsin-square root transformed before testing; the values for potassium and biomass were log-transformed to achieve normality and homogeneity of variances; numbers of inflorescences were rank-transformed within a year.

Analysis of multivariate data on plant community composition (list of species with separate cover estimates) started with simple DCA ordinations that indicated relatively homogeneous data (length of gradient always <2 multivariate standard deviations, McCune et al. 2002). Fertilisation effects were tested with non-parametric Permutation-MANOVAs for a given year (Anderson 2001), which were based on Euclidean distances. These were followed by pair-wise comparisons of treatments within years; significances were tested with 14,999 permutations. Finally, treatments within 1 year were pooled according to results of pair-wise comparisons, and the resulting groupings were assessed with Indicator Species Analysis (Dufréne and Legendre 1997). This identified species which were significantly more abundant in any given treatment, and those were subjected to further analyses. Univariate statistics were calculated with SPSS 12.0 (SPSSInc. 2003); multivariate tests with PC-ORD 5.0 (McCune and Mefford 2006).

Results

Soil nutrient contents

Fertilisation in 2003 changed soil nutrient contents in 2004 (Table 2a). Available P and K increased significantly, and total content of soil K also increased with fertilisation. The total content of soil-N increased from a mean of 1.7 g/kg in the control to some 1.9 g/kg following the addition of 20 gN/m², although the effect was not significant. Similar trends were observed in the total organic C content and in CN-ratios.

Subsequent analyses in 2005 showed that nutrients accumulated in the soil (Table 2b). Soil exchangeable P was higher on plots that were fertilised over 2 years, and the increase was strongest on plots that received the equivalent of 20 gN/m² in both years. Post hoc tests indicated that plots first fertilised in 2003 formed a significantly different subgroup, while those fertilised in 2004 for the first time were intermediate. A similarly stronger effect of fertilisation over 2 years was observed for exchangeable K, but here plots fertilised once in 2004 with 20 gN/m² were also significantly different from the controls. Again, total N contents were not significant among treatments, although contents tended to increase with repeated fertilisation (up to a mean of 2.5 g/kg for 2 × 20 gN/m²) and were higher overall compared to 2004. This increase was also observed on the controls.

Plant community composition

Mean species richness on unfertilised plots was 10.0 ± 0.5 (=1 s.e.) per 0.20 m² in 2004, 8.1 ± 0.5/0.2 m² in 2005 and 9.8 ± 0.6/0.2 m in 2006. Differences among years reflected the higher numbers of annuals (mainly Chenopodiaceae), which germinated successfully after heavy rains in early 2004 and late 2006. Fertilisation treatments showed no effect on species richness, but plant community composition was altered (Table 3). PerMANOVAs demonstrated significant treatment effects for all years, and post hoc tests almost unequivocally distinguished controls from fertilised plots. Fertilisation effects tended to increase over time and were most pronounced in 2006. The effects were altogether not huge as indicated by initial DCA ordinations (data not shown), but Indicator Species Analysis revealed constantly positive responses of the two most abundant species Allium polyrrhizum and Agropyron cristatum. These were treated separately in the following analyses.

Biomass production and flowering activity

Biomass development in 2003/2004 showed a pronounced increase with fertilisation levels (Fig. 1). Fertilisation at 10 gN/m² almost doubled the total above-ground growth up until August 2004, from a mean of 615 ± 50 (s.e.) kg dry biomass/ha to 1130 ± 70 kg/ha, and fertilisation at 20 gN/m² raised the mean value to 1490 ± 140 kg/ha. Plots had not been harvested prior to July 2004, but growth in the 4 weeks of July to August 2004 was equally affected by fertilisation (see Electronic supplementary material). Mean growth was 190 ± 20 kg/ha on the controls, while fertilised plots had values of 340 ± 20 and 420 ± 40 kg/ha, respectively. Fertilisation effects were significant (Table 4), but although increases seemed more pronounced in Allium spp. and Agropyron cristatum (Fig. 1), differences among species groups and species*fertilisation interactions were not significant after Bonferroni correction (Table 4).

Effect of fertilisation on standing crop of the three main species groups Agropyron cristatum, Allium polyrrhizum and Al. prostratum, and rest. Harvests for July and August were summed up for a given year (columns indicate means + 1 s.e. of the mean total biomass; small letters indicate subgroups for fertilisation effects according to Tukey’s post hoc test). See Electronic supplementary material for raw data of the different harvests

Biomass productivity for 2005 was lower due to the generally lower amounts of precipitation, but effects of fertilisation were nonetheless pronounced (Fig. 1). The plots fertilised for the first time in 2004 were not harvested that year, so they carried over amounts of biomass (including necromass from 2004). After harvesting in July 2005, possible confounding effects of necromass were eliminated and growth for August 2005 still showed the expected pattern (Electronic supplementary material). Biomass on plots fertilised for two years at 20 gN/m² had a mean total annual growth of 805 ± 80 kg/ha, those fertilised at 2 × 10 gN/m² had 595 ± 60 kg/ha compared to 350 ± 25 kg/ha for the controls. Post hoc comparisons indicated that the highest fertilisation treatment (2 years at 20 gN/m²) differed from the control, the intermediate treatments were also different from the control but there was some overlap with the high fertilisation treatment (Fig. 1).

In 2006, we skipped the harvest in July due to pronounced dryness in early summer (Table 1)—resulting in next to zero growth—and harvested plots only once at the beginning of August. Fertilisation effects were again strong (Table 4) and growth increased more than threefold from 235 ± 20 kg/ha on the control to 740 ± 75 kg/ha on plots fertilised three times at 20 gN/m². Fertilisation treatments differed significantly from the control, but not among each other (Fig. 1). As before, species’ responses seemed to differ, and in 2006 differences among species groups were indeed significant. Effects were most pronounced in Agropyron cristatum, which increased in growth from 35 ± 10 kg/ha to 150–170 kg/ha on the intermediate treatments, and 285 ± 70 kg/ha under the most intense fertilisation.

Flowering activity also responded to fertilisation. In July 2004, the total number of inflorescences more than doubled under high levels of fertilisation (Fig. 2), and was intermediate in the intermediate treatment. In both July 2005 and August 2006, inflorescence numbers were much lower on all treatments, including the control, and there was pronounced scatter within treatments. Fertilisation effects were significant in the moist year of 2004 (Bonferroni corrected P < 0.01); there were also trends in 2005 and 2006, great scatter, however, resulted in non-significant tests (Bonferroni corrected P < 0.2 in 2005, P < 0.15 in 2006).

Total number of inflorescences in response to fertilisation treatments. Results of block-factor ANOVAs on rank-transformed data (pooled for all species) were significant after Bonferroni correction in 2004 (F 2,16 = 10.123, P corr < 0.01, small letters indicate results of Tukey’s post hoc test) but not in 2005 (F 4,32 = 2.254, P corr < 0.2) and 2006 (F 4,32 = 2.756, P corr < 0.15). Error bars give 1 s.e. of the total number of inflorescences

Plant nutrient contents

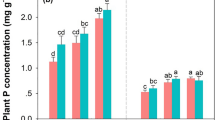

Plant nutrient contents were only analysed for the two most abundant species groups and only in the year 2004 (both harvests, Fig. 3). Plant nutrient contents for the second harvest were generally higher, as a consequence of more fertiliser being applied after the harvest in July and perhaps due to lower water availability. Fertiliser addition in 2003 unequivocally increased the nitrogen content in both Agropyron cristatum and Allium spp. (mainly Al. polyrrhizum, Fig. 3), although levels were overall higher in Al. polyrrhizum. The fertilisation effect was not directly related to the absolute amount of fertilisation (within the range tested here), as post hoc tests discriminated mostly the unfertilised controls from fertilisation treatments (Fig. 3). CN ratios in August decreased in Al. polyrrhizum from a mean of 9.3 ± 0.1 (s.e.) on the controls to 7.8 ± 0.2 and 7.3 ± 0.1 at 10 and 20 gN/m². The corresponding figures in Ag. cristatum were 14.3 ± 0.6, 10.3 ± 0.2 and 9.7 ± 0.3. Fertilisation also resulted in increased levels of P and K in tissues (Table 5). In Ag. cristatum, the content of P showed an almost linear increase with fertilisation, and a similar trend was observed for K. Phosphorus increase in Al. polyrrhizum was less pronounced (significant species*fertilisation interaction), and the species also responded less strongly to K addition (significant species*fertilisation interaction). Post hoc tests showed differences between both treatments and the control for P, while for K treatments also differed among each other (Fig. 3).

Effect of fertilisation on plant nutrient contents in 2004, given for the main fodder grass Agropyron cristatum and the second common species group Allium polyrrhizum and Al. prostratum (columns indicate means + 1 s.e., small letters indicate subgroups according to Tukey’s post hoc test following the Repeated Measures ANOVA)

Discussion

Soil nutrient contents

Levels of exchangeable soil K were significantly increased by fertilisation, but they are already high even on the controls, and comparable to adjacent regions (Fernandez-Gimenez and Allen-Diaz 2001; Xie and Wittig 2004). In contrast, levels of soil total N and available P are relatively low, and both can be limiting in desert environments (Drenovsky and Richards 2004; James et al. 2005; Krueger-Mangold et al. 2004; Whitford 2002). The low levels of nitrogen may be related to the generally low abundance of nitrogen-fixing plants in Central Asia (Lavrenko and Karamysheva 1993), but they are also influenced by land use. Livestock consume biomass and translocate nutrients via their deposits, with gradients in N usually being less steep than in phosphorus (Fernandez-Gimenez and Allen-Diaz 2001; Knopf et al. 2005; Stumpp et al. 2005). Grazing may also trigger erosion, and nutrient stocks in heavily grazed Central Asian drylands are often very low (Cheng et al. 2004; Su et al. 2005; Xie and Wittig 2004).

We could not find significant fertilisation effects on the total soil N content. With a mean content of 1.7 g/kg in 2004 and a mean bulk density of 1.4 g/cm³ (Ronnenberg unpubl.), total soil N-content in the topsoil (upper 10 cm) was around 240 g/m² for the controls. Thus, assuming no losses, an addition of 20 g should result in an estimated overall increase from 1.7 g/kg to ca. 1.9 g/kg. This represents a small effect difficult to detect statistically, but one which corresponds well with our observations (Table 2), indicating that a large fraction of the added N was still present in the soil. The additional nitrogen absorbed by plants is of limited importance here, because it accounts for <20% of added nutrient (see discussion below). The low soil C/N ratios (7–9) indicate that the largest part of the nitrogen is not bound to humus fractions or other organic matter. Uptake is nonetheless apparently not complete, be it because of limited rootlet density, lack of water or any other factor co-limiting plant growth.

At the prevailing pH levels of around 7–8 (Table 2), P is increasingly fixed in poorly soluble phosphates and should be quickly immobilised. This adds to the adsorption to organic compounds (Marschner 1995), although in our case fertilisation improved P availability. If the evidence on nutrient translocation is considered, there is still good reason to suspect phosphorus limitation in southern Mongolian steppes. In any case, soil nutrient analysis confirmed that N and P accumulated in the soil and fertilisation had a pronounced and presumably lasting effect on soil nutrient contents and availability.

Effects on total above-ground biomass

We found clear evidence that above-ground plant production, and thereby fodder availability, benefited from fertilisation. Standing crop had almost doubled with every 10 gN/m² fertiliser equivalent in the moist spring/early summer 2004, and trends were similar for summer growth in subsequent years. There was some evidence of a saturation effect at a total of 2 years of 20 gN/m² fertilisation; beyond which treatments showed only modest and non-significant additional increases (Fig. 1).

The absolute size of the effect seems to be related to climate because growth on fertilised sites up to July was much higher in 2004 than in the drier years of 2005 and 2006. Still the fertilisation effect was apparent in all years regardless of their precipitation in line with the meta-analysis by Hooper and Johnson (1999). Our results also support reports on nutrient co-limitation in North American saline shrublands growing at 140 mm mean annual precipitation (James et al. 2005), and fertilisation experiments in Californian grasslands that indicate co-limitation of N and water at ambient precipitation of 226 mm (Harpole et al. 2007). New evidence is also becoming available from Mongolia, where sites were fertilised at relatively low rates of up to 1.5 gN/m² (Kinugasa et al. 2008). That study found a trend to increasing productivity, but results were not significant due to large scatter. This may be related to the comparatively low amounts of N added, and to the fact that P may also be a limiting factor (see below).

Our data should be representative for larger dryland regions. At the study site, August precipitation was between 20 and 45 mm in all three years (Table 1). These are not unusually high figures for the region, as even drier desert steppes in the area receive a mean total of 28 mm in August as evidenced by Bayandalay station (National Meteorological Service), which lies in drier steppes 700 vertical metres lower than the study site. Increased productivity was observed within grazing exclosures in those dry desert steppes, and soils in these exclosures showed indeed higher levels of nutrients than in the surroundings (Slemnev et al. 2004; Wesche et al. accepted). Further indirect evidence is provided by studies on positive effects of improved soil conditions on vegetation after erosion controls were implemented in a northern Chinese dune region with 190 mm mean annual precipitation (Li et al. 2007).

North American short grass prairies are similar in physiognomy to the vegetation of our study sites but tend to receive more annual precipitation than the 100–200 mm found in southern Mongolia (Lauenroth and Milchunas 1992). Compared to North America, precipitation in the highly continental regions of Central Asia is strongly concentrated to the ca. 4 months of growing season. Even in dry Central Asia, plants can thus utilise a monthly mean of 20 and 50 mm in the growth period, which is not exceedingly low compared to most dry regions of the world (Whitford 2002) and explains why precipitation levels were sufficiently high to allow nutrient uptake and usage in our experiment.

Our data thus support the notion that nutrient co-limitation may be an issue even under dry conditions, which was put initially forward in the benchmark publication by Breman and de Wit (1983). This seems contradictory to a recent review compiled by Xia and Wan (2008) who describe a strong correlation of relative responses to nitrogen fertilisation and ambient precipitation, but a closer look at their data reveals that this relationship is largely driven by studies from very wet environments (>1250 mm), while differences in response ratios between dry sites and sites with 750–1000 mm are not as pronounced. Moreover, inferences by Xia and Wan (2008) on very dry environments are largely based on data from a site in the Swiss Alps, which was erroneously entered as having a mean annual precipitation of 94 mm.

Other effects on plants

Our results clearly show that nutrient limitation may constrain flower and, thus, seed production. Sexual recruitment is severely constrained in the harsh climate of the Gobi (e.g. Gunin et al. 2003; Lavrenko and Karamysheva 1993; Ronnenberg et al. 2008) and nutrient limitation may aggravate these problems. In the long run, this should also lead to changes in plant community composition. In our case, fertilisation altered plant community composition towards a higher cover of Ag. cristatum, but data are tentative with respect to scale and duration of the experiment.

Agropyron cristatum is the preferred fodder grass in southern Mongolia (Jigjidsuren and Johnson 2003) and it showed the strongest response. The relative contribution of Ag. cristatum to total standing crop in August 2004 increased from a mean of 31% on the control to 38% on the most intensively fertilised plots; the corresponding figures for 2005 were 26 and 33%; in 2006 Ag. cristatum contributed 15% on the controls and 35% at the highest fertilisation level. Although the Allium species are even more nutritious than the grasses (Jigjidsuren and Johnson 2003), secondary compounds lead to a reduced palatability, which makes the relative increase of Ag. cristatum biomass desirable from a land use point of view. Moreover, mean nitrogen content of Ag. cristatum in August was already 30 g/kg in the controls, which is high but comparable to values from other Central Asian grasses (Yuan et al. 2005a; Yuan et al. 2005b). Contents increased up to a mean of 44 g/kg under the most intense level of N-addition, which is again in line with meta-analysis (Xia and Wan 2008). As leaf nitrogen is closely related to leaf protein content (Marschner 1995), fodder quality should have benefited. This is in contrast to an ongoing study from Central Mongolia, where unpalatable species disproportionally benefited from experimental nutrient addition (Kinugasa et al. 2008), so more data are clearly needed.

Expressed in total aboveground stocks for August, tissue N in Allium spp. increased from a mean of 2.7 ± 0.4 kg/ha on the controls to 6.3 ± 1.3 and 8.5 ± 1.8 kg/ha at the equivalents of 100 and 200 kgN/ha and year fertilisation, the corresponding figures for Ag. cristatum were 2.0 ± 0.3, 6.2 ± 1.0 and 8.5 ± 2.1 kg/ha, respectively. Therefore, only a small fraction of fertiliser N was used by the main plant groups. The corresponding figures for leaf P for Allium spp. are 0.094 ± 0.021, 0.170 ± 0.035 and 0.264 ± 0.054 kg/ha and for Ag. cristatum 0.099 ± 0.015, 0.279 ± 0.046 and 0.421 ± 0.091 (compared to equivalents of 0, 33 and 66 kg P/ha year added).

Given that we opted for full fertilisation, we can make no direct inferences on the limiting factor. Some of the added micro elements may have been limiting, but with respect to the overall high cation contents N and P are more likely candidates. The NP ratios found in our plants (on average 20–35) are in the upper range of values reported for Central Asian plants (Han et al. 2005; He et al. 2008) and point to phosphorus rather than nitrogen limitation, but this indicator has to be taken with caution (Güsewell 2004). Ratios did not change or even slightly increase with fertilisation; an effect that has been observed before in desert environments simultaneously fertilised with N and P (Drenovsky and Richards 2004).

Phosphorus availability is known to influence flowering and fruit-setting in plants (Marschner 1995) and we indeed found enhanced flowering activity. Whether this is related directly to P uptake—as opposed to a function of the general better growth and performance of plants growing on fertilised soil—cannot be inferred without a differential fertilisation experiment. This would allow estimating the importance of the presumably co-limiting factors N and P. Water should be included, as comparisons of years with different precipitation imply that water availability co-limited plant growth.

Management implications

In the moist year of 2004, the mean biomass increase with an annual fertilisation of 200 kgN/ha (or 20 gN/m²) was 875 kg/ha, while the respective figures for the drier years of 2005 and 2006 were 455 and 505 kg/ha. Thus, in 2004, we obtained on average around 4.4 more units of above-ground biomass for every unit of N invested; in 2005, the factor was 2.3 and in 2006 2.6. Total production was certainly higher because at grazed sites around our camp >95% of biomass is below-ground (unpublished data). Still, nutrient use efficiencies are relatively low (Hooper and Johnson 1999; Yuan et al. 2006), and we thus certainly do not suggest a large-scale fertilisation of the dry Mongolian steppes.

However, our results demonstrate that nutrient availability constrains fodder production in rather dry rangelands at well <200 mm, and focussing solely on precipitation variability certainly is an oversimplification. Problems with nutrient availability may aggravate. The quoted evidence for nutrient translocation may be related to ongoing replacement of large livestock such as Camels by goats and sheep, which tend to distribute their faeces less evenly in space (Bakker et al. 2004). Annual nitrogen depositions in Central Asia are predicted to increase by 0.4 g/m² between 1990 and 2050 (Galloway et al. 2004). This may counterbalance some of the effects caused by animal husbandry, but the estimated scale of the presumably already accomplished nitrogen translocation shows that effects of aerial N deposition will be limited. Our data thus show a potential and certainly largely overlooked pathway for pasture degradation, which should prompt further research on the issue.

References

Anderson MJ (2001) A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol 26:32–48

Bakker ES, Olff H, Boekhoff M, Gleichman JM, Berendse F (2004) Impact of herbivores on nitrogen cycling: contrasting effects of small and large species. Oecologia 138:91–101

Bedunah D, Schmidt SM (2004) Pastoralism and protected area management in Mongolia’s Gobi Gurvansaikhan National Park. Dev Change 35:167–191

Borisova IV, Popova TA (1985) Biogeozönologische Untersuchungen der Steppenwüsten und Wüstensteppen der nördlichen Gobi. Fed Repert 96:409–423

Breman H, De Wit CT (1983) Rangeland productivity and exploitation in the Sahel. Science 221:1341–1346

Breymeyer A, Klimek K (eds) (1983) Mongolian dry steppe ecosystems—a case study from Gurvan Turuu area. Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geography, Wroclaw

Cheng X, An S, Liu S, Li G (2004) Microscale spatial heterogeneity and the loss of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in degraded grasslands in Ordos Plateau, northwestern China. Plant Soil 259:29–37

Christensen L, Coughenour MB, Ellis JE, Zuo ZC (2004) Vulnerability of the Asian typical steppe to grazing and climatic change. Clim Change 63:351–368

Drenovsky RE, Richards JH (2004) Critical N:P values: predicting deficiencies in desert shrublands. Plant Soil 259:59–69

Dufréne M, Legendre P (1997) Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol Monogr 67:345–366

Elser JJ, Bracken MES, Cleland EE, Gruner DSW, Harpole S, Hillebrand H, Ngai JT, Seabloom EW, Shurin JB, Smith JE (2007) Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol Lett 10:1135–1142

Fernandez-Gimenez ME, Allen-Diaz B (2001) Vegetation change along gradients from water sources in three grazed Mongolian ecosystems. Plant Ecol 157:101–118

Galloway JN, Dentener FJ, Capone DG, Boyer EW, Howarth RW, Seitzinger SP, Asner GP, Clevelands CC, Green PA, Holland EA, Karl DM FMA, Porter JH, Townsend AR, Vörösmarty C (2004) Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry 70:153–226

Gunin PD, Slemnev NN, Tsoog S (2003) Seed regeneration of dominant plants in ecosystems of the desert zone of Mongolia: dynamics of undergrowth populations. Bot Zur 88:1–17

Güsewell S (2004) N:P ratios in terrestrial plants: variation and functional significance. New Phytol 164:243–266

Gutierrez JR, Da Silva OA, Pagani MI, Weems D, Whitford WG (1988) Effects of different patterns of supplemental water and nitrogen fertilization on productivity and composition of Chihuahuan desert annual plants. Am Midl Nat 119:336–343

Han W, Fang J, Guo D, Zhang Y (2005) Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry across 753 terrestrial plant species in China. New Phytol 168:377–385

Harpole WS, Potts DL, Suding KN (2007) Ecosystem responses to water and nitrogen amendment in a California grassland. Global Change Biol 13:2341–2348

He J-S, Wang L, Flynn DFB, Wang X, Ma W, Fang J (2008) Leaf nitrogen:phosphorus stoichiometry across Chinese grassland biomes. Oecologia 155:301–310

Holst J, Liu C, Yao Z, Brüggemann N, Zheng X, Han X, Butterbach-Bahl K (2007) Importance of point sources on regional nitrous oxide fluxes in semi-arid steppe of Inner Mongolia, China. Plant Soil 296:209–226

Hooper DU, Johnson L (1999) Nitrogen limitation in dryland ecosystems: responses to geographical and temporal variation in precipitation. Biogeochemistry 46:247–293

James JJ, Tiller RL, Richards JH (2005) Multiple resources limit plant growth and function in a saline-alkaline desert community. J Ecol 93:113–126

Jigjidsuren S, Johnson DA (2003) Forage plants in Mongolia. Admon Publishing, Ulaanbaatar

Kinugasa T, Shinoda M, Tsunekawa A (2008) Increasing nitrogen distribution and grassland productivity in Mongolia. In: Organizing Committee of IGC/IRC Congress (ed) Multifunctional grasslands in a changing world. Guangdongs People’s Publishing House, Guangzhou, p 614

Knopf C, Werhahn G, Tsogtbataar J (2005) Vegetation in relation to the distance to grazing hotspots—results of four transects in Khovd-Aimag (western Mongolia). In: Dorjsuren C, Dorofeyuk NI, Gunin PD, Drobyshev YI, Bazha SN, Vasilieva LF (eds) Ecosystems of Mongolia and frontier areas of adjacent countries: natural resources, biodiversity and ecological prospects. Proceedings of the international conference. Publishing House “Bembi San”, Ulaanbaatar, pp 216–218

Krueger-Mangold J, Sheley R, Engel R, Jacobsen J, Svejcar T, Zabinsiki C (2004) Identification of the limiting resource within a semi-arid plant association. J Arid Environ 58:309–320

Kutschera L, Sobotik M, Lichtenegger E (1997) Bewurzelung von Pflanzen in verschiedenen Lebensräumen. 5. Band der Wurzelatlas-Reihe. Stapfia 49, Linz

Lauenroth WK, Milchunas DG (1992) Short-grass steppe. In: Coupland RT (ed) Natural grasslands. Ecosystems of the world 8A. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 183–226

Lavrenko EM, Karamysheva ZV (1993) Steppes of the former Soviet Union and Mongolia. In: Coupland RT (ed) Natural grasslands. Ecosystems of the world 8B. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 3–59

LeBauer DS, Treseder KK (2008) Nitrogen limitation of net primary productivity in terrestrial ecosystems is globally distributed. Ecology 89:371–379

Li XR, Kong DS, Tan HJ, Wang XP (2007) Changes in soil and vegetation following stabilisation of dunes in the southeastern fringe of the Tengger Desert, China. Plant Soil 300:221–231

Liu P, Sun OJ, Huang J, Li L, Han X (2007a) Nonadditive effects of litter mixtures on decomposition and correlation with initial litter N and P concentrations in grassland plant species of northern China. Biol Fert Soils 44:211–216

Liu W, Xu W, Han Y, Wang C, Wan S (2007b) Responses of microbial biomass and respiration of soil to topography, burning, and nitrogen fertilization in a temperate steppe. Biol Fert Soils 44:259–268

Marschner H (1995) Mineral nutrition of higher plants. Academic Press, San Diego

McCune B, Mefford MJ (2006) PC-ORD 5.0 multivariate analysis of ecological data. MjM Software, Gleneden Beach, Oregon

McCune B, Grace JB, Urban DL (2002) Analysis of ecological communities. MjM Software Design, Gleneden Beach, Oregon

Munkhtsetseg E, Kimura R, Wang J, Shinoda M (2007) Pasture yield response to precipitation and high temperature in Mongolia. J Arid Environ 70:94–110

Pan Q-M, Bai Y-F, Han X-G, Yang J-C (2005) Effects of nitrogen additions on a Leymus chinensis population in a typical steppe of China. Acta Phytoecol Sin 29:311–317

Paschke MW, McLendon T, Redente EF (2000) Nitrogen availability and old-field succession in a shortgrass steppe. Ecosystems 3:144–158

Retzer V (2004) Carrying capacity and forage competition between livestock and a small mammal, the Mongolian Pika (Ochotona pallasi) in a non-equilibrium ecosystem, South-Gobi, Mongolia. Görich & Weiershäuser Verlag, Marburg

Ronnenberg K, Wesche K, Hensen I (2008) Germination ecology of Central Asian Stipa spp: differences among species, seed provenances, and the importance of field studies. Plant Ecol 196:269–280

Slemnev NN, Sanjid D, Khongor T, Tsooj S (2004) The features of desertified steppes development in Mongolia at the gradient of ecotopes’ moistoning. Arid Ecosyst 10:172–182

Sokal RM, Rohlf FJ (1995) Biometry. W. H. Freeman & Co, New York

SPSSInc (2003) SPSS for Windows 12.0G. SPSS Inc., Chicago

Stumpp M, Wesche K, Retzer V, Miehe G (2005) Impact of grazing livestock and distance from water points on soil fertility in southern Mongolia. Mt Res Dev 25:244–251

Su Y-Z, Li Y-L, Zhao W-Z, Cui J-Y (2005) Influences of continuous grazing and livestock exclusion on soil properties in a degraded sandy grassland, Inner Mongolia, northern China. Catena 59:267–278

Underwood AJ (1997) Experiments in ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Veron SR, Paruelo JM, Osterheld M (2006) Assessing desertification. J Arid Environ 66:751–763

Weiner J, Gorecki A, Perzanowski K (1982) The effect of rodents on the rate of matter and energy cycling in ecosystems of arid steppe of central eastern Mongolia. Pol Ecol Stud 8:69–82

Wesche K, Miehe S, Miehe G (2005) Plant communities of the Gobi Gurvan Sayhan National Park (South Gobi Aimag, Mongolia). Candollea 60:149–205

Wesche K, Nadrowski K, Retzer V (2007) Habitat engineering under dry conditions: the impact of pikas (Ochotona pallasi) on southern Mongolian mountain steppes. J Veg Sci 18:665–674

Wesche K, Ronnenberg K, Retzer V (accepted) Effects of herbivore exclusion in southern Mongolian desert steppes. Acta Oecol

White RP, Murray S, Rohweder M (2000) Pilot analysis of global ecosystems Grassland ecosystems. World Resource Institute, Washington

Whitford WG (2002) Ecology of desert systems. Academic Press, London

Xia J, Wan S (2008) Global response patterns of terrestrial plant species to nitrogen addition. New Phytol 179:428–439

Xiao C, Janssens IA, Liu P, Zhou Z, Sun OJ (2007) Irrigation and enhanced soil carbon input effects on below-ground carbon cycling in semiarid temperate grasslands. New Phytol 174:835–846

Xie Y, Wittig R (2004) The impact of grazing intensity on soil characteristics of Stipa grandis and Stipa bungeana steppe in northern China (autonomous region of Ningxia). Acta Oecol 25:197–204

Yuan Z-Y, Li L-H, Han X-G, Huang J-H, Jiang G-M, Wan S-Q (2005a) Soil characteristics and nitrogen resorption in Stipa krylovii native to northern China. Plant Soil 273:257–268

Yuan Z-Y, Li L-H, Han X-G, Huang J-H, Jiang GM, Wan SQ, Zhang W-H, Chen QS (2005b) Nitrogen resorption from senescing leaves in 28 plant species in a semi-arid region of northern China. J Arid Environ 63:191–202

Yuan Z-Y, Li L-H, Han X-G, Chen X-P, Wang Z-W, Chen Q-S, Bai W-M (2006) Nitrogen response efficiency increased monotonically with decreasing soil resource availability: a case study from a semiarid grassland in northern China. Oecologia 148:564–572

Zheng YR, Xie ZX, Robert C, Jiang LH, Shimizu H (2006) Did climate drive ecosystem change and induce desertification in Otindag sandy land, China over the past 40 years? J Arid Environ 64:523–541

Acknowledgements

The local administration in southern Mongolia kindly gave permission to carry out the research. Financial assistance was provided by the German Science Foundation (DFG), the German Federal Ministry of Cooperation (BMZ), the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ), the German Academic Exchange Service and the Schimper-Foundation. We are grateful to R. Samjaa, R. Undrakh, H. von Wehrden and other colleagues in the Gobi Gurvan Saykhan Research Project for their assistance during data collection and analysis, F. Haß, C. Bläß and R. Treiber helped with laboratory work, D. McCluskey kindly proofread our English. The manuscript benefited much from comments by two anonymous referees. This is contribution No. 295 in the series ‘Results of the German-Mongolian Biological expeditions since 1962’.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wesche, K., Ronnenberg, K. Effects of NPK fertilisation in arid southern Mongolian desert steppes. Plant Ecol 207, 93–105 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-009-9656-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-009-9656-6