Abstract

Extant research in political science has demonstrated that citizens’ opinions on policies are influenced by their attachment to the party sponsoring them. At the same time, little evidence exists illuminating the psychological processes through which such party cues are filtered. From the psychological literature on source cues, we derive two possible hypotheses: (1) party cues activate heuristic processing aimed at minimizing the processing effort during opinion formation, and (2) party cues activate group motivational processes that compel citizens to support the position of their party. As part of the latter processes, the presence of party cues would make individuals engage in effortful motivated reasoning to produce arguments for the correctness of their party’s position. Following psychological research, we use response latency to measure processing effort and, in support of the motivated reasoning hypothesis, demonstrate that across student and nationally representative samples, the presence of party cues increases processing effort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To the extent that we are able to provide evidence for this role of agreement with a policy in modulating reasoning effort, this would be very hard to account for in a learning perspective. The unexpectedness of a piece of information (and, hence, the need to learn it) should be independent of whether one agrees or disagrees with that information. At least, if anything, it makes more sense to argue that an incongruent policy from a liked party is more unexpected (and, hence, requires more learning effort) if the individual disagrees with that policy. The motivated reasoning perspective, however, makes the directly opposite prediction: that agreeing with an incongruent policy from a liked party is more effortful.

See Table A1 in the online appendix for further information on sample representativeness.

To investigate whether the randomization procedure worked, we tested, using χ2, whether subjects in the two conditions differed on gender, age, geographical region, and vote choice. None of the tests revealed any significant differences (p-values ranged from .10 to .75).

Some researchers in American politics propose distinguishing between party identification and related measures (see, e.g., Green et al. 2002). However, not only do sympathy scores seem to be more valid indicators of party attachments in multiparty systems (Rosema 2006), the classic way of measuring party identification (developed as it is in a two-party system) creates other methodological problems. Because of the abundance of parties, it will always be a minority of subjects who explicitly label themselves as identifiers with any two parties. In this respect, sympathy scores are preferable because they allow us to gauge fine-grained differences in levels of attachment between all subjects rather than simply lumping most of our subjects into one big ‘non-identifier’ category. At the same time, using sympathy scores should not make much difference as these measures are highly collinear with measures of party identification. In the survey, we also obtained the classic measure of party identification. 187 subjects identified either with the SPP or DPP. The correlations between sympathy scores and identifying with DPP compared to SPP are −.92 (p < .000) in the case of sympathy for SPP and .95 (p < .000) in the case of sympathy for DPP.

This measurement not only follows extant research but is also the most parsimonious way to test our predictions. It could, however, be deemed inadequate for two reasons. First, it builds on the assumption that the effect of sympathy is similar across the two conditions (i.e., in the face of both SPP and the DPP). Second, at the outset, it does not allow us to directly test whether the predicted effects arise from sympathizing specifically with the sponsor or from sympathizing with just any party. Importantly, we deal thoroughly with both issues below (see footnotes 6 and 11). Here, we directly verify that the effects are indifferent across the two conditions and are related to sympathizing specifically with the sponsor.

Additional analyses demonstrate that this effect of party sympathy is, first, the same across the two parties used in the study (i.e., whether the policy was sponsored by SPP or by DPP) and, second, specifically linked to sympathy for the sponsor rather than sympathy for any party. Specifically, we created a measure of sympathy for the non-sponsor (e.g., sympathy for DDP when SPP sponsored the policy). We then added two three-way interaction terms to the model presented in Table 1 with all lower-order terms between, first, agreement, party sympathy, and party sponsor (to test whether the effect was the same across conditions) and, second, agreement, sympathy for non-sponsor, and party sponsor (to test whether the effects were specifically linked to sympathy for the sponsor). Consistent with our expectations, only one interaction term emerged as significant from this extended model: the interaction between party sympathy and agreement (F = 6.22; p = .01).

We also tested whether this interaction was robust to the inclusion of key demographic variables and included measures of gender, age, education, and geographical location. If anything, these controls increased the effect of the two-way interaction (after control: F = 14.91, p < .001; before control: F = 10.41, p = .001).

In addition, we use a number of control strategies to control for differences across the experimental conditions left by the pseudo-randomized design. In testing the Costly Support Hypothesis, we focus only on the two (pooled) conditions with statements from a party. Here, a strong control option is available, and this analysis is controlled for the individual proposition in the form of a series of dummy variables. In this way, all potential differences between propositions have been controlled for. We also test the effect of the mere presence of party cues (see footnote 13). Here, we compare the conditions with parties to the condition without parties. The stronger control option is not available because the set of dummy variables is completely collinear with the condition variable because of the pseudo-randomized design. Therefore, to achieve some level of control, we include the length of the individual statements (specifically, their number of characters) as a control variable.

Note that although differences between agreeing and disagreeing respondents are similar in Study 1 and 2, the actual level of the response latency cannot be compared directly. In Study 1, latency is measured in unknown environments (some respondents will be interrupted when completing the web survey), while Study 2 is executed in the lab. In Study 1, latencies included delays caused by internet traffic; in Study 2, they were recorded precisely by software. Finally, Study 2 had a time limit; Study 1 did not. This resulted in considerably longer response latencies in Study 1 (median = 14,930 ms) compared to Study 2 (median = 5,991 ms).

Previous studies have shown that the presence of incongruent information increases response latency (Redlawsk 2002; Huckfeldt et al. 2005); we find a similar effect in our data. In a non-interactive model, a main effect of party consistency on response latency is found, such that responses are prolonged when the statement is party-inconsistent (F 1,77 = 7.21, p = .009). As discussed in the section on our predictions, this simple effect cannot explain the complicated three-way interaction effect entailed by the motivated reasoning perspective.

Again, additional analyses demonstrate that this interactive effect of party sympathy is the same across the two parties used in the study (i.e., regardless whether the policy was sponsored by SPP or by DPP) and is specifically linked to sympathy for the sponsor rather than sympathy for any party. Following the logic specified in footnote 6, we expanded the model presented in Table 2. Specifically, we added two four-way interaction terms with all lower-order terms between, first, agreement, party sympathy, party consistency of the policy, and party sponsor (to test whether the effect was the same across conditions) and, second, agreement, sympathy for the non-sponsor, party consistency of the policy, and party sponsor (to test whether the effects were specifically linked to sympathy for the sponsor). Consistent with our expectations, the three-way interaction term between agreement, party sympathy, and party consistency of the policy was robust to the inclusion of these extra terms (F = 13.50; p = .0004). In addition, neither the three-way interaction term with sympathy for non-sponsor nor the two four-way interaction terms were significant at the .05-level.

Given the focus of the heuristic perspective on the moderating effects of political awareness, one could perhaps wonder whether the observed sensitivity to the ideological content of the proposals is due to the use of a politically aware student sample. This is, however, not the case. Hence, we obtained the exact same measure of political awareness in Study 2 as in Study 1, and a comparison reveals that the student sample in Study 2 is actually less aware than the average citizen. On a scale from 0 to 1, the mean awareness in our representative sample (Study 1) is .57, while the mean awareness in the student sample (Study 2) is .42. In addition, we have tested whether the predicted effects are moderated by the students’ political awareness, but this is not the case. Hence, the four-way interaction term with political awareness is insignificant (p = .62).

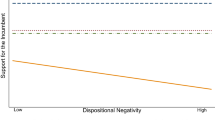

The statements in the no-party condition were labelled by a visual cue of size, colour, and complexity similar to the party cues (see Fig. 2). The comparison shows that the availability of party cues significantly prolongs the response time with 213 ms (F 1,77 = 20.39, p < .0001). Effort is, in other words, increased rather than decreased in the face of party cues.

In other cases, party cues provide very limited information. This is the case for issues not related to the more general positions of parties. For instance, Hobolt (2007) argues that party cues on issues related to European integration will provide limited information in most European countries.

References

Bassili, J. N. (1993). Response latency versus certainty as indexes of the strength of voting intentions in a Cati survey. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 57, 54–61.

Bassili, J. N. (1995). On the psychological reality of party identification: Evidence from the accessibility of voting intentions and of partisan feelings. Political Behavior, 17, 339–358.

Bullock, J. G. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review, 105, 496–515.

Burdein, I., Lodge, M., & Taber, C. (2006). Experiments on the automaticity of political beliefs and attitudes. Political Psychology, 7, 359–371.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. (1960). The American voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 808–822.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Belmont: Wardsworth Group/Thomson Learning.

Fazio, R. H. (1990). A practical guide to the use of response latency in social psychological research. In C. Hendrick & M. S. Clark (Eds.), Research methods in personality and social psychology (pp. 74–97). Sage, Thousand Oaks: Review of Personality and Social Psychology.

Goren, P. (2005). Party identification and core political values. American Journal of Political Science, 49, 881–896.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20, 393–403.

Greitemeyer, T., Fischer, P., Frey, D., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2009). Biased assimilation: The role of source position. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 22–39.

Habyarimana, J., Humphreys, M., Posner, D. N., & Weinstein, J. M. (2007). Why does ethnic diversity undermine public goods provision? American Political Science Review, 101, 709–725.

Hobolt, S. B. (2007). Taking cues on Europe? Voter competence and party endorsements in referendums on European integration. European Journal of Political Research, 46, 151–182.

Huckfeldt, R., Levine, J., Morgan, W., & Sprague, J. (1999). Accessibility and the political utility of partisan and ideological orientations. American Journal of Political Science, 43, 888–911.

Huckfeldt, R., Mondak, J. J., Craw, M., & Mendez, J. M. (2005). Making sense of candidates: Partisanship, ideology, and issues as guides to judgment. Cognitive Brain Research, 23, 11–23.

Huckfeldt, R., & Sprague, J. (2000). Political consequences of inconsistency: The accessibility and stability of abortion attitudes. Political Psychology, 21, 57–79 (Special issue: Response latency measurement in telephone surveys).

Jennings, K. M., & Niemi, R. G. (1974). The political character of adolescence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jennings, K. M., & Niemi, R. G. (1981). Generations and politics: A panel study of young adults and their parents. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kam, C. D. (2005). Who toes the party line? Cues, values, and individual differences. Political Behavior, 27, 163–182.

Koch, J. W. (2001). When parties and candidates collide: Citizen perception of house candidates’ positions on abortion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 65, 1–21.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivating reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 480–498.

Kurzban, R., Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2001). Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98, 15387–15392.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 951–971.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). How voters decide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Layman, G. C., & Carsey, T. M. (1998). Why do party activists convert? An analysis of individual-level change on the abortion issue. Political Research Quarterly, 51, 723–749.

Lebo, M. J., & Cassino, D. (2007). The aggregated consequences of motivated reasoning and the dynamics of partisan presidential approval. Political Psychology, 28, 719–746.

Malhotra, N., & Kuo, A. G. (2009). Emotions as moderators of information cue use. American Politics Research, 37, 301–326.

Malhotra, N., & Margalit, Y. (2010). Short-term communication effects or longstanding dispositions? The public’s response to the financial crisis of 2008. Journal of Politics, 72, 852–867.

Matz, D. C., & Wood, W. (2005). Cognitive dissonance in groups: The consequences of disagreement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 22–37.

McDermott, R. (2007). Cognitive neuroscience and politics: Next steps. In R. Neumann, G. Marcus, A. Crigler, & M. MacKuen (Eds.), The affect effect (pp. 375–397). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mondak, J. J. (1993). Source cues and policy approval: The cognitive dynamics of public support for the Reagan agenda. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 186–212.

Mulligan, K., Grant, T. J., Mockabee, S. T., & Monson, J. Q. (2003). Response latency methodology for survey research: Measurement and modelling strategies. Political Analysis, 11, 289–301.

Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. (1990). The adaptive decision maker: Effort and accuracy in choice. In R. M. Hogarth (Ed.), Insights in decision making (pp. 129–153). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Petersen, M. B. (2012). Social welfare as small-scale help: Evolutionary psychology and the deservingness heuristic. American Journal of Political Science, 56, 1–16.

Petersen, M. B., Slothuus, R., Stubager, R., & Togeby, L. (2010). Political parties and value consistency in public opinion formation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74, 530–550.

Petersen, M. B., Slothuus, R., Stubager, R., & Togeby, L. (2011). Deservingness versus values in public opinion on welfare: The automaticity of the deservingness heuristic. European Journal of Political Research, 50, 24–52.

Petersen, M. B., Sznycer, D., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2012). Who deserves help? Evolutionary psychology, social emotions and public opinion about welfare. Political Psychology, 33, 395–418.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary approaches. Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown.

Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 134–148.

Pietraszewski, D., Curry, O., Petersen, M. B., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. (2012). Politics erases race but not sex: Evidence that signals of political party support engage coalitional psychology. Working paper.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 472–496.

Redlawsk, D. P. (2002). Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision-making. Journal of Politics, 64, 1021–1044.

Rosema, M. (2006). Partisanship, candidate evaluations, and prospective voting. Electoral Studies, 25, 467–488.

Schaffner, B. F., & Streb, M. J. (2002). The partisan heuristic in low information elections. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66, 559–581.

Slothuus, R., & de Vreese, C. H. (2010). Political parties, motivated reasoning, and issue framing effects. The Journal of Politics, 72, 630–645.

Squire, P., & Smith, E. R. A. N. (1988). The effect of partisan information on voters in nonpartisan elections. The Journal of Politics, 50, 169–179.

Stanton, S. J., Beehner, J. C., Saini, E. K., Kuhn, C. M., & LaBar, K. S. (2009). Dominance, politics, and physiology: Voters’ testosterone changes on the night of the 2008 United States Presidential Election. PLoS ONE, 4, e7543. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007543.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 755–769.

van Harreveld, F., van der Pligt, J., de Vries, N. K., Wenneker, C., & Verhue, D. (2004). Ambivalence and information integration in attitudinal judgment. British Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 431–447.

Westen, D., Blagov, P. S., Harenski, K., Kilts, C., & Hamann, S. (2006). Neural bases of motivated reasoning: An FMRI study of emotional constraints on partisan political judgment in the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 1947–1958.

Yamagishi, T., & Mifune, N. (2008). Does shared group membership promote altruism? Fear, greed, and reputation. Rationality and Society, 20, 5–30.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lene Aarøe, Jamie Druckman and Rune Slothuus for helpful comments and advice in preparing this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petersen, M.B., Skov, M., Serritzlew, S. et al. Motivated Reasoning and Political Parties: Evidence for Increased Processing in the Face of Party Cues. Polit Behav 35, 831–854 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-012-9213-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-012-9213-1