Abstract

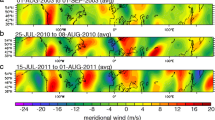

The urban heat island (UHI), together with summertime heat waves, foster’s biophysical hazards such as heat stress, air pollution, and associated public health problems. Mitigation strategies such as increased vegetative cover and higher albedo surface materials have been proposed. Atlanta, Georgia, is often affected by extreme heat, and has recently been investigated to better understand its heat island and related weather modifications. The objectives of this research were to (1) characterize temporal variations in the magnitude of UHI around Metro Atlanta area, (2) identify climatological attributes of the UHI under extremely high temperature conditions during Atlanta’s summer (June, July, and August) period, and (3) conduct theoretical numerical simulations to quantify the first-order effects of proposed mitigation strategies. Over the period 1984–2007, the climatological mean UHI magnitude for Atlanta-Athens and Athens-Monticello was 1.31 and 1.71°C, respectively. There were statistically significant minimum temperature trends of 0.70°C per decade at Athens and −1.79°C per decade at Monticello while Atlanta’s minimum temperature remained unchanged. The largest (smallest) UHI magnitudes were in spring (summer) and may be coupled to cloud-radiative cycles. Heat waves in Atlanta occurred during 50% of the years spanning 1984–2007 and were exclusively summertime phenomena. The mean number of heat wave events in Atlanta during a given heat wave year was 1.83. On average, Atlanta heat waves lasted 14.18 days, although there was quite a bit of variability (standard deviation of 9.89). The mean maximum temperature during Atlanta’s heat waves was 35.85°C. The Atlanta-Athens UHI was not statistically larger during a heat wave although the Atlanta-Monticello UHI was. Model simulations captured daytime and nocturnal UHIs under heat wave conditions. Sensitivity results suggested that a 100% increase in Atlanta’s surface vegetation or a tripling of its albedo effectively reduced UHI surface temperature. However, from a mitigation and technological standpoint, there is low feasibility of tripling albedo in the foreseeable future. Increased vegetation seems to be a more likely choice for mitigating surface temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Beniston M (2004) The 2003 heat wave in Europe: a shape of things to come? An analysis based on Swiss climatological data and model simulations. Geophys Res Lett 31:2022–2026. doi:10.1029/2003GL018857

Bornstein RD, Oke T (1980) Influence of pollution on urban climatology. Adv Environ Sci Eng 3:171–202

Bornstein R, Lin Q (2000) Urban heat islands and summertime convective thunderstorms in Atlanta: three case studies. Atmos Environ 34:507–516. doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00374-X

Bornstein R, Balmori RTF, Taha H, Byun D, Cheng B, Nielsen-Gammon J, Burian S, Stetson S, Estes M, Nowak D, Smith P (2006) Modeling the effects of land-use/land-cover modifications on the urban heat island phenomena in Houston, Texas. Final report to David Hitchcock Houston Advanced Research Center, 100 pp

Brazel A, Gober P, Lee SJ, Grossman-Clarke S, Zehnder J, Hedquist B, Comparri E (2007) Determinants of changes in the regional urban heat island in metropolitan Phoenix (Arizona, USA) between 1990 and 2004. Clim Res 33:171–182. doi:10.3354/cr033171

Changnon SA, Kunkel KE, Reinke BC (1996) Impacts and responses to the 1995 heat wave: a call to action. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77:1497–1506. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<1497:IARTTH>2.0.CO;2

Dixon PG, Mote TL (2003) Patterns and causes of Atlanta’s urban heat island—initiated precipitation. J Appl Meteorol 42:1273–1284. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(2003)042<1273:PACOAU>2.0.CO;2

Estes M Jr, Quattrochi D, Stasiak E (2003) The urban heat island phenomenon: how its effects can influence environmental decision making in your community. Public Manage 85(00333611):8

Ezber Y, Lutfi Sen O, Kindap T, Karaca M (2007) Climatic effects of urbanization in Istanbul: a statistical and modeling analysis. Int J Climatol 27:667. doi:10.1002/joc.1420

Grimmond CSB, Oke TR (1999) Heat storage in urban areas: local-scale observations and evaluation of a simple model. J Appl Meteorol 38:922–940. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1999)038<0922:HSIUAL>2.0.CO;2

Haffner J, Kidder SQ (1999) Urban heat island modeling in conjunction with satellite-derived surface/soil parameters. J Appl Meteorol 38:448–465. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1999)038<0448:UHIMIC>2.0.CO;2

Ignatov A, Minnis P, Loeb N, Wielicki B, Miller W, Sun-Mack S, Tanré D, Remer L, Laszlo I, Geier E (2005) Two MODIS aerosol products over ocean on the Terra and Aqua CERES SSF datasets. J Atmos Sci 62:1008–1031. doi:10.1175/JAS3383.1

Jin M, Dickinson RE, Zhang D (2005) The footprint of urban areas on global climate as characterized by MODIS. J Clim 18:1551–1565. doi:10.1175/JCLI3334.1

Jin M, Shepherd JM, Peters-Lidard C (2007) Development of a parameterization for simulating the urban temperature hazard using satellite observations in climate model. Nat Hazards 43:257–271. doi:10.1007/s11069-007-9117-2

Kalkstein LS (1993) Direct impacts in cities. Lancet 342(8884):1397–1399. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)92757-K

Kim YH, Baik JJ (2002) Maximum urban heat island intensity in Seoul. J Appl Meteorol 41:651–659. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(2002)041<0651:MUHIII>2.0.CO;2

Kunkel KE, Changnon SA, Reinke BC, Arritt RW (1996) The July 1995 heat wave in the Midwest: a climatic perspective and critical weather factors. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77:1507–1518. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<1507:TJHWIT>2.0.CO;2

Kusaka H, Kimura F, Hirakuchi H, Mizutori M (2000) The effects of land-use alteration on the sea breeze and daytime heat island in the Tokyo metropolitan area. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 78:405–420

Liptan T, Miller T, Roy A (2004) Portland Ecoroof Vision: quantitative study to support policy decisions. Greening rooftops for sustainable communities, Portland

Liu Y, Chen F, Warner T, Swerdlin S, Bowers J, Halvorson S (2004) Improvements to surface flux computations in a non-local-mixing PBL scheme, and refinements on urban processes in the Noah land-surface model with the NCAR/ATEC real-time FDDA and forecast system. 20th conference on weather analysis and forecasting/16th conference on numerical weather prediction, Seattle, Washington, 11–15 January, 2004

Lynn BH, Carlson TN, Rosenzweig C, Goldberg R, Druyan L et al (2009) A modification to the NOAH LSM to simulate heat mitigation strategies in the New York City metropolitan area. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 48:199–216. doi:10.1175/2008JAMC1774.1

Manley G (1958) On the frequency of snowfall in metropolitan England. Q J R Meteorol Soc 84:70–72. doi:10.1002/qj.49708435910

McKee TB, Doesken NJ, Davey CA, Pielke RA Sr (2000) Climate data continuity with ASOS, report for period April 1996 through June 2000. Climatology report 00-3, Department of Atmospheric Science, CSU, Fort Collins, CO, 82 pp

McPherson EG (1994) Energy-saving potential of trees in Chicago. Chicago’s urban forest ecosystem: results of the Chicago urban forest climate project, pp 95–114

Meehl GA, Tebaldi C (2004) More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science 305:994–997. doi:10.1126/science.1098704

Menne B (2003) The health impacts of 2003 summer heat-waves. Briefing note for the delegations of the fifty-third session of the WHO regional committee for Europe. WHO Europe, 12 pp

Mote TL, Lacke MC, Shepherd JM (2007) Radar signatures of the urban effect on precipitation distribution. A case study for Atlanta, Georgia. Geophys Res Lett 34:L20710. doi:10.1029/2007GL031903

NWS (1995) Natural disaster survey report: July 1995 heat wave. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service, Washington, DC

Ohashi Y, Kida H (2002) Local circulations developed in the vicinity of both coastal and inland urban areas: a numerical study with a mesoscale atmospheric model. J Appl Meteorol 41:30–45. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(2002)041<0030:LCDITV>2.0.CO;2

Oke TR (1981) Canyon geometry and the nocturnal urban heat island: comparison of scale model and field observations. J Climatol 1:237–254. doi:10.1002/joc.3370010304

Oke TR (1982) The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q J R Meteorol Soc 108:1–24

Palecki MA, Changnon SA, Kunkel KE (2001) The nature and impacts of the July 1999 heat wave in the midwestern United States: learning from the lessons of 1995. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 82:1353–1368. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(2001)082<1353:TNAIOT>2.3.CO;2

Quattrochi DA, Luvall JC, Estes MG Jr (1999) Project ATLANTA (Atlanta land use analysis: temperature and air quality): use of remote sensing and modeling to analyze how urban land use change affects meteorology and air quality through time. NASA/TP-2147483647

Quattrochi DA, Lapenta W, Crosson W, Estes M, Limaye A, Khan M (2006) The application of satellite-derived, high-resolution land use/land cover data to improve urban air quality model forecasts, NASA/TP-2006-214710

Robinson PJ (2001) On the definition of a heat wave. J Appl Meteorol 40:762–775. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(2001)040<0762:OTDOAH>2.0.CO;2

Rosenzweig C, Solecki WD, Parshall L, Chopping M, Pope G, Goldberg R (2005) Characterizing the urban heat island in current and future climates in New Jersey. Global Environ Change B. Environ Hazards 6:51–62. doi:10.1016/j.hazards.2004.12.001

Sailor DJ (1995) Simulated urban climate response to modifications in surface albedo and vegetative cover. J Appl Meteorol 34:1694–1704

Sailor DJ (2003) Streamlined mesoscale modeling of air temperature impacts of heat island mitigation strategies. Final report. Portland State University, 31 pp

Sailor DJ, Kalkstein LS, Wong E (2002) The potential of urban heat island mitigation to alleviate heat-related mortality: methodological overview and preliminary modeling results for Philadelphia. In: Proceedings of the 4th symposium on the urban environment. May 2002, Norfolk, VA, 4:68–69

Schrumpf AD (1996) Temperature data continuity with the automatic surface observing system. Thesis for the Degree of Master of Science, Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, 256 pp

Shem W, Shepherd JM (2008) On the impact of urbanization on summertime thunderstorms in Atlanta: two numerical model case studies. Atmos Res 92:172–189. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2008.09.013

Shepherd JM (2005) A review of current investigations of urban-induced rainfall and recommendations for the future. Earth Interact 9:1–27. doi:10.1175/EI156.1

Shepherd JM, Pierce H, Negri AJ (2002) Rainfall modification by major urban areas: observations from spaceborne rain radar on the TRMM satellite. J Appl Meteorol 41:689–701. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(2002)041<0689:RMBMUA>2.0.CO;2

Skamarock WC, Klemp JB, Dudhia J (2001) Prototypes for the WRF (Weather Research and Forecasting) model. Preprints. Ninth conference on mesoscale processes, 5 pp

Souch C, Grimmond S (2006) Applied climatology: urban climate. Prog Phys Geogr 30:270–279. doi:10.1191/0309133306pp484pr

Sterl A, Severijns C, Dijkstra H, Hazeleger W, Oldenborgh G, Broeke M, Burgers G, Hurk B, Leeuwen P, Velthoven P (2008) When can we expect extremely high surface temperatures? Geophys Res Lett. doi:10.1029/2008GL034071

Synnefa A, Dandou A, Santamouris M, Tombrou M, Soulakellis N (2008) On the use of cool materials as a heat island mitigation strategy. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 47:2846–2856. doi:10.1175/2008JAMC1830.1

Taha H (1996) Modeling impacts of increased urban vegetation on ozone air quality in the South Coast Air Basin. Atmos Environ 30:3423–3430. doi:10.1016/1352-2310(96)00035-0

Taha H (1997) Modeling the impacts of large-scale albedo changes on ozone air quality in the South Coast Air Basin. Atmos Environ 31:1667–1676. doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(96)00336-6

Taha H (1999) Modifying a mesoscale meteorological model to better incorporate urban heat storage: a bulk-parameterization approach. J Appl Meteorol 38:466–473. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1999)038<0466:MAMMMT>2.0.CO;2

Taha H, Douglas S, Haney J (1997) Mesoscale meteorological and air quality impacts of increased urban albedo and vegetation. Energy Build 25:169–177. doi:10.1016/S0378-7788(96)01006-7

Tewari M, Chen F, Wang W (2004) Implementation and verification of the unified NOAH land surface model in the WRF model. 20th conference on weather analysis and forecasting/16th conference on numerical weather prediction, 11–15

Unger J, S¨umeghy Z, Zoboki J (2001) Temperature cross-section features in an urban area. Atmos Res 58:117–127. doi:10.1016/S0169-8095(01)00087-4

Yang X, Lo CP (2003) Modeling urban growth and landscape change for Atlanta metropolitan region. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 17:463–488. doi:10.1080/1365881031000086965

Yoshino M (1975) Climate in a small area. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo 549 pp

Yow DM (2007) Urban heat islands: observations, impacts, and adaptation. Geogr Compass 1(6):1227–1251. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00063.x

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the NASA PMM program for funding that partially supported this research. The authors would like to thank Drs. Thomas L. Mote and Andrew Grundstein for useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Shepherd, J.M. Atlanta’s urban heat island under extreme heat conditions and potential mitigation strategies. Nat Hazards 52, 639–668 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9406-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9406-z