Abstract

This article summarizes the findings of a study of community-wide strategies for preventing homelessness among families and single adults with serious mental illness, conducted for the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. The study involved six communities, of which this article focuses on five. A major finding of this study was that it was difficult to identify sites with community-wide strategies, and even harder to find any that maintained data capable of documenting prevention success. However, the five communities selected for this study presented key elements of successful strategies including mechanisms for accurate targeting, a high level of jurisdictional commitment, significant mainstream agency involvement, and mechanisms for continuous system improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Closing the “front door” to homelessness by helping people avoid their first homeless episode is essential if the United States is to end homelessness. In theory, to end homelessness it is as important to prevent it as it is to help those who are already homeless to reenter housing (National Alliance to End Homelessness 2000).

Virtually every community in the United States offers a range of activities to prevent homelessness. The most widespread activities provide assistance to avert housing loss for households facing eviction. Other activities focus on moments when people are particularly vulnerable to homelessness, such as at discharge from institutional settings. Given that the causes and conditions of becoming homeless are often multifaceted, communities use a variety of strategies to prevent homelessness. This article summarizes a recent study funded by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) on community-wide strategies for preventing homelessness among families and individuals with serious mental illness.

Why homelessness prevention?

The intent of prevention is to stop something from happening. The worse the effects of what one is trying to prevent, the more important it is to develop effective prevention strategies, and the more one is willing to accept partial prevention if complete prevention is not possible.

Homelessness is an undesirable condition, both for the people it affects and for society in general. The effects of homelessness on children demonstrate why many communities offer interventions to help keep families with children in housing. Compared to poor housed children, homeless children have worse health (i.e., asthma, upper respiratory infections, minor skin ailments, gastrointestinal ailments, parasites, and chronic physical disorders); more developmental delays; more anxiety, depression, and behavior problems; poorer school attendance and performance; and other negative conditions (Buckner 2004; Shinn and Weitzman 1996). There are also indications that negative effects increase as the duration of homelessness continues, including more health problems (possibly from living in congregate shelters or in cars and other places not meant for habitation) and more mental health symptoms due to the loss of social support and poor school attendance (Buckner 2004).

Even housing instability negatively impacts children. Analyses of the National Health Interview Survey show strong associations between changing residences three or more times and increased behavioral, emotional, and school problems (Shinn and Weitzman 1996). Even if families receiving prevention assistance would not become literally homeless without assistance, reducing the number of times they move may be worth the investment of paying rent, mortgage, or utility arrearages.

Effects of homelessness on parents in homeless families are similar to those of their children, with the exception of school-related problems (Shinn and Weitzman 1996). The effects of homelessness on single adults are also grim. Homeless individuals report poorer health (37% versus 21% for poor housed adults), and are more likely to have life-threatening contagious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS (Weinreb et al. 2004).

The risk of homelessness is relatively high among poor households in the United States. About one in 10 poor adults and children experience homelessness every year (Burt et al. 2001; Culhane et al. 1994; Link et al. 1994, 1995). Homelessness exacerbates the negative effects of extreme poverty on families and individuals.

Despite the theoretical importance of prevention as the only intentional practice that will reduce the number of new cases of homelessness, public funders are often reluctant to invest in homelessness prevention strategies. In part, this reluctance stems from fear that funds could benefit people not likely to become homeless so that fewer public resources would go to people already homeless or be invested in effective prevention activities.

What makes a good prevention strategy?

To prevent something from happening, one needs to know what causes it or have the ability to predict in advance when, or to whom, it will happen. This knowledge improves the odds of designing effective interventions. Research has identified many antecedents of homelessness that can serve as predictors, but these do not predict homelessness with certainty. For example, in their groundbreaking study comparing poor housed and homeless families in New York City, NY, Shinn and her colleagues (1998) were able to classify a family as homeless or not homeless only 66% of the time. The prediction equation used 10 factors, including race and ethnicity, childhood poverty, being pregnant or having an infant, being married or living with a partner, current domestic violence, childhood disruption, and four housing factors—overcrowding, doubling up, not having a housing subsidy, and frequent moves. The single factor “facing eviction” predicted homelessness only 20% of the time.

Few communities desiring to prevent homelessness among families will be able to eliminate these risk factors, at least in the short run. But communities can use knowledge of these factors to increase the odds of delivering homelessness prevention services to families who would very likely become homeless without it. Communities can use the identified predictive factors mentioned above to screen families for high homelessness risk and then target resources toward the highest-risk families and individuals.

Factors differentiating ever from never homeless adults include the presence of mental health, substance abuse, and chronic physical health problems. Adverse childhood experiences including physical and sexual abuse and out-of-home placement also predicted the likelihood that an adult had experienced homelessness (Burt et al. 2001).

The challenge of creating effective prevention strategies

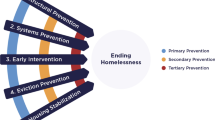

This study concentrated on the primary prevention of homelessness, on preventing new cases of homelessness and stopping people from ever becoming homeless. It also examined secondary and tertiary prevention activities, but only as part of a community’s comprehensive prevention strategy. Secondary prevention focuses on intervening early during a first spell of homelessness to help the person leave homelessness and not return. Tertiary prevention activities seek to end long-term homelessness, thus preventing continued homelessness.

It is relatively easy to offer prevention activities, but difficult to develop an effective community-wide prevention strategy. Such a strategy needs to offer effective prevention activities and do so efficiently. Effective activities must be capable of stopping someone from becoming homeless (primary prevention) or ending their homelessness quickly (secondary prevention). An efficient system must target well, delivering its effective activities to people who are very likely to become homeless without help.

Inefficiency is widely considered to be the common failing of local prevention strategies and activities; they simply target too broadly. Recipients of the intervention are not uniformly at very high risk of homelessness, so relatively few would actually become homeless without the intervention. A prevention strategy is not efficient and “wastes” resources if it uses them to assist people who would not have become homeless without the service. Briefly stated, poor targeting leads to an inefficient strategy, and inefficient strategies are rarely effective.

By what standard should one judge the effectiveness of a prevention activity? The answer to this question depends on the type of prevention one attempts. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the US Department of Health and Human Services maintain a website called “The Guide to Community Prevention Services” (www.thecommunityguide.org), on which it recommends activities whose effectiveness is considered proven for preventing health problems as diverse as suicide, youth violence, and smoking. Rates of change achieved by prevention activities in this guide range from very low for primary prevention activities to very high for tertiary interventions. Raising the price of cigarettes reduces smoking initiation by about 4%, and, when combined with extensive media campaigns, by about 8%. At the other extreme, therapeutic foster care for chronically delinquent violent youth produces a 70% reduction in violence compared to regular group home treatment. The lesson for homelessness prevention efforts is that sometimes even relatively small impacts may be judged effective when the issue is primary prevention, but that one should expect somewhat greater changes for interventions designed for secondary and tertiary prevention.

Method

The objectives of this study were to (a) identify communities that have implemented community-wide strategies to prevent homelessness and can document their effectiveness; (b) describe these strategies and their component activities for other communities and the field at large; and (c) review community data that measure achievements in preventing homelessness and provide evidence that the prevention activities were effective.

Common prevention activities

We examined 2004 Continuum of Care applications to identify the prevention activities that communities conduct. We identified one cluster of activities—counseling and advocacy to help households connect to resources and housing and budget and credit counseling—in almost every application. Most applications also included in-kind emergency assistance such as food and clothing and cash assistance with rent, mortgage, or utility payments to avert eviction.

A smaller proportion of communities also offered the following: legal and other assistance to retain housing; mental health, corrections, child welfare, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) service commitments; and strategies that involve more than one public agency working together to prevent homelessness.

Selecting communities to study

Armed with a general knowledge of prevention activities and target populations we sought communities to include in this study that represented a range of approaches and focal populations, and also met two criteria specified by HUD:

-

1.

Communities have a community-wide strategy of providing primary homelessness prevention activities in a structured and coordinated way.

-

2.

Communities have data to document that prevention efforts do or do not work.

To identify appropriate communities, we contacted national experts on homelessness to identify potential sites, and then canvassed the communities identified to see if they met the study criteria. This canvass identified six communities that met both HUD criteria reasonably well—this article considers the three communities focused on preventing family homelessness and the two focused on homelessness prevention for people with serious mental illness. (The sixth community was working to help street youth leave homelessness, and thus was not an example of primary prevention.) The lead agencies in the communities described here are: Hennepin County Human Services Department in Minnesota; Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services in Maryland; Mid America Assistance Coalition (MAAC) in the five counties comprising the larger Kansas City, Kansas and Missouri area; Department of Mental Health (DMH) serving the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; and, Office of Behavioral Health (OBH) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Site visits were conducted to all communities, during which we interviewed key stakeholders in the prevention strategies and learned about the history of their approach, their primary coordination mechanisms, their funding sources, and their future plans. We also explored the options for analyzing their data to document prevention effectiveness. If data existed but had not been analyzed in a manner appropriate to our purposes, we worked with local people to develop analysis plans, and in some cases also participated in the actual data analysis.

Results

The first three communities were included to examine their strategies for primary homelessness prevention for families. The last two were included to examine their strategies for primary and secondary prevention for single adults with serious mental illness.

The communities focused on primary homelessness prevention for families—Hennepin County, Montgomery County, and MAAC—served families with short-term problems. Although they often discovered family issues that could not be resolved with 1 month of cash assistance, for primary prevention they selected the families whose housing problems could be resolved with the resources that were available. These communities offered families cash assistance to prevent eviction and cover rent, mortgage, or utility arrears, along with other prevention activities such as in-kind assistance and budget counseling.

The other communities—Massachusetts and Philadelphia—focused their attention on people who would need long-term help. Of course, these communities found less severely disabled people during screenings, but they selected the ones who needed the most help. In keeping with the nature and needs of the population being served, these communities offered more intense, more expensive, and longer-term interventions than the family-focused communities. Permanent housing and supportive services were key activities, as were collaborations among two or more mainstream agencies to launch these approaches.

Some of the more intensive prevention activities serve multiple purposes. For example, the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (DMH) uses four interventions—mental health services, supportive services to maintain housing, rent subsidies, and permanent supportive housing—to accomplish both primary and secondary prevention and also to end chronic homelessness. Supportive and mental health services help keep never-homeless people with serious mental illness in housing and also help formerly-homeless people stay in their new homes. In addition, the same intervention can be effective with different populations. For example, Hennepin County has a well-developed rapid exit program to assist families with multiple housing barriers to leave shelter and sustain their new housing. Massachusetts DMH also has a rapid exit strategy to assist homeless people with serious mental illness to leave shelters and the streets.

Promising (or potentially effective) homelessness prevention strategies

This study identified five prevention activities used in the study communities that may be implemented at all levels of prevention: primary, secondary, and tertiary. These activities, many of which have documented research effectiveness, may be used alone or in combination as part of a coherent community-wide strategy.

-

1.

Housing subsidies. Shinn et al. (2001) documented the effectiveness of housing subsidies at keeping at least 80% of first-time homeless families housed for a minimum of 2 years (Stojanovic et al. 1999). Rog et al. (1995) demonstrated similar success (80–85% retention over at least 18 months) for homeless families in which a parent’s mental illness complicated housing stability. Evidence from simulations (Quigley et al. 2001) indicates that housing subsidies had the greatest effect of several potential interventions in reducing homelessness.

-

2.

Supportive services coupled with permanent housing. For adults with serious mental illness, with or without co-occurring substance-related disorders, alone or in families, permanent supportive housing provided along with community-based outreach and case management prevents initial homelessness, rehouses people quickly if they become homeless, and helps chronically homeless people leave the streets (Burt et al. 2004; Shern et al. 1997; Tsemberis and Eisenberg, 2000; Tsemberis et al. 2004). In combination with supportive services, effective discharge planning involving housing was offered in two study communities as part of secondary and tertiary prevention efforts. Evidence from Massachusetts indicates declining rates of homelessness among admissions to state psychiatric hospitals over the 10-year period during which housing with supportive services was expanding (See Fig. 1).

-

3.

Mediation in housing courts. Evidence collected in the present study on the effectiveness of mediation under the auspices of Housing Courts shows the ability to preserve tenancy, even after a landlord has filed for eviction. Sixty-nine percent of cases filed against families in the Hennepin County Housing Court were settled without eviction and the family retained housing. Mediation preserved housing for up to 85% of single adults with serious mental illness facing eviction in the Western Massachusetts Tenancy Preservation Project (See Table 1). Compared to the housing outcomes of similar people who were waitlisted but did not receive services, this project cut the proportion becoming homeless by at least one-third.

-

4.

Cash assistance for rent or mortgage arrears. This commonly used primary prevention activity for households still in housing but threatened with housing loss can be effective—the challenge is to make its administration well-targeted and efficient. In the study communities, 2–5% of families receiving assistance became homeless during the following year. In contrast, a study in New York City using a comparison group of families facing imminent eviction who did not receive an intervention to prevent homelessness determined that 20% of the families become homeless (Shinn et al. 2001; Stojanovic et al. 1999).

-

5.

Rapid exit from shelter. These innovative secondary prevention activities are directed toward families just entering shelter, to ensure that they quickly leave shelter and stay housed thereafter. With this strategy, Hennepin County halved the average length of shelter stay (from 60 days to 30 days) and achieved an 88% success rate in keeping formerly homeless families from returning to shelter during the following 12 months.

Changes in Massachusetts DMH community residential capacity and changes in proportion of homeless admissions and discharges, 1991–2003. Note: Numbers are in 1000s of people. Comparison is of changes in homeless admissions and discharges as a percentage of all admissions to DMH continuing care units excluding Metro Boston, 1991–2003

Key elements of prevention strategies

Any agency may use effective prevention activities, alone or in combination, and will probably prevent some homelessness. But prevention resources are unlikely to be used efficiently unless they are part of a larger structure of planning and organization that addresses the issue of targeting. To get the most from a community’s prevention dollar, findings from this study indicate that one needs a community-wide system with a carefully articulated targeting strategy and mechanisms to assure that funds for prevention reach the people at greatest risk of homelessness. The communities in this study each had some elements of such a system, and several had many. Based on the evidence from this study, Hennepin County and Massachusetts were more likely to prevent homelessness and document this achievement.

The elements found in the study communities that appear to contribute to homelessness prevention are related to community organization of one type or another. The elements include:

-

1.

Elements affecting ability to target well. These include agencies and systems sharing information, through a single data system or tracking clients across different systems as well as a single agency or system controlling the eligibility determination process, including agreed-upon criteria combined with housing barrier screening and triage.

-

2.

Elements related to community motivation. The community accepts an obligation to shelter one or more at-risk populations—the obligation may come as county council policy, as statutory requirement, as a governor’s commitment, or through other mechanisms. Given this obligation, the jurisdiction accepts that it must provide funds to fulfill it and is motivated to use them wisely.

-

3.

Elements related to maximizing resources. Collaboration among public and private agencies helps stretch resources and creates new resources when two or more organizations work together to identify a need and then develop a service that did not previously exist (e.g., mediation in Housing Courts). Nonhousing mainstream agencies accept responsibility for their clients’ housing stability.

-

4.

Elements affecting direction, sustainability, control, and the use of data to guide future development. Leadership is essential at two levels: agency heads and public figures must commit to developing and sustaining a community-wide prevention strategy. A community member must have the job to “mind the store,” manage the strategy, analyze performance, and promote collaboration. Several elements are involved in making this happen: (a) a clear goal of preventing homelessness and a strategy to reach the goal; (b) feedback mechanisms to measure progress, stimulate new thinking and innovation, and identify gaps and next steps; and (c) knowing the needs and ensuring contract agencies meet them.

We identified two overall strategies for organizing a community for prevention. The first, most commonly applied to families threatened with housing loss, screens for short-term problems that constitute crises for particular families, and applies short-term solutions. The second seeks people whose disabilities or other circumstances indicate chronic problems, and applies the long-term solutions of housing with supportive services. When these solutions are made available before homelessness occurs, they have a stabilizing and preventive effect similar to what happens when they are offered to chronically homeless people with disabilities (see Table 2 for a complete list of organizing elements by population type).

These strategies operate through several mechanisms that other communities could develop. These mechanisms include careful targeting toward populations at very high risk of homelessness, and organizing and controlling access to preventive services to maximize targeting. The best organized among the study communities reached their present situation deliberately and over time, in a process that involved, and continues to involve, leadership, analytic thinking, strategic planning, alliance building, and collaboration. Developing better data and using existing data more strategically can improve performance, identify and fill gaps, and further the development of a community’s approach to homelessness prevention.

Documenting prevention effectiveness

A community should establish routine systems to assess both the effectiveness and efficiency of its prevention efforts and use the resulting feedback to improve its targeting and balance among prevention activities. However, commitment to such performance monitoring is rare, as this study’s search for communities with performance data indicated.

Each of the study communities collected basic data and could describe who they served and what services they provided. Some communities had sophisticated linkages among service providers, while others had more centralized databases. Approaches that the communities used to document prevention effectiveness included the following.

-

1.

Matching against emergency shelter records. This performance monitoring approach requires a prevention database and a shelter database, each of which should cover all or most of the relevant services. Each database must have a field or fields that permits matching a household in one database with the same household in the other database. The database containing information identifying households that received help to avoid homelessness is matched to a database such as a homeless management information system showing which households used shelter. Knowing when a household received prevention assistance, the shelter database is queried to learn whether that household used shelter at any time during the following 12 months.

-

2.

Changes over time documented within a single database. Evidence over time that fewer people who received homelessness prevention services are becoming homeless increases the confidence that a system is moving toward greater prevention. This movement could reflect several changes that would indicate that prevention is occurring: decreasing numbers of households are requesting shelter, only households with the most complex problems are requesting shelter, or decreasing proportions of people are homeless at psychiatric facility intake and discharge. Hennepin County and Massachusetts DMH documented outcomes of this type.

-

3.

Special data collection. Even in the absence of formal databases or the ability to match across databases, specific prevention interventions can maintain records to document prevention effectiveness. The Tenancy Preservation Project in Massachusetts is one example. It maintained records on all people assisted and tracked housing outcomes. As it had a waitlist and some people never received services, it was also able to construct a small comparison group of people similar to those receiving services, and was able to show substantial differences in outcomes between the two.

Discussion: Implications for policy and practice

The implications of study findings are clear for communities that want to mount effective and efficient homelessness prevention strategies and for funders that want to support such efforts. First, offer only prevention activities for which research has indicated some effectiveness. Second, recognize that efficiency is as important as effectiveness and that services should be targeted to families and individuals most likely to become or remain homeless without help. Third, organize the community. Fourth, develop useful data systems and use the data to reflect and improve system performance.

The role of funding agencies

No single agency or program has the resources needed to prevent homelessness. Every study community recognized the need for collaboration among key players to bring more resources to the table. The primary differences among the communities were in the nature of the players and the resources they commanded. Where public agencies led or shaped prevention strategies, the resultant activities commanded many more resources and offered more comprehensive approaches.

Funders considering support for homelessness prevention, including governments, foundations, or service agencies using charitable donations, should pay attention to the effectiveness of prevention activities and the likelihood that community organization is adequate to assure careful targeting. They should also consider funding the organizational capacity itself, as having staff responsible for seeing that the system works well is an important element in developing a well-functioning system.

In addition, state and local governments and private funders may accept multiple goals for an activity, of which homelessness prevention would be only one. Paying rent, mortgage, and utility arrearages or offering in-kind assistance and budget counseling may serve more than one purpose, and funder goals may include providing crisis relief to extremely poor households whether or not they face a high homelessness risk. If this is the case in a community, performance monitoring should reflect the success of several outcomes that an intervention is expected to achieve, not only homelessness prevention.

Federal, state, and local government resources are widely used to support homelessness prevention. Federal resources include Emergency Shelter Grants, the Emergency Food and Shelter Program, Projects for Assistance in Transition from Homelessness (PATH), and several block grants. Significant state and local commitments were obvious in several study communities. The government agencies responsible for these funding streams might emphasize the role of prevention in community-wide strategic planning and integrated approaches for reducing homelessness for those at greatest risk. Funding agencies interested in homelessness prevention should assemble and disseminate information about prevention activities, the circumstances under which they are effective, and how they are integrated into a community-wide strategy. Federal and state agencies should make technical assistance widely available to communities to improve targeting and the measurement of outcomes.

Future research

This study has only scratched the surface of homelessness prevention, assembling data from a few communities that could begin to reflect the effectiveness of their prevention efforts. Other researchers (Lindblom 1996; Shinn et al. 2001) have concluded that there is not strong evidence that homelessness prevention efforts are effective, with the issue being targeting and inefficiency, not the underlying effectiveness of different activities. Developing powerful evidence on the effectiveness of prevention activities requires sophisticated and expensive research to assess what would have happened if particular families or disabled people were not assisted. Minimally, research needs to compare over time persons who receive prevention assistance with those who do not, where receipt of assistance is the only difference.

Conclusions

This study found examples of promising policies and practices that could be adapted to local circumstances and applied by other communities. The communities in this study each had some elements of a community-wide system, and several had many. The study communities with the most elements, Hennepin County and Massachusetts, were best at preventing homelessness and certainly best able to document their achievements in homelessness prevention.

For a community looking for the most effective and efficient approaches, the evidence suggests that secondary prevention and institutional discharge options offer the highest degree of appropriate targeting coupled with acceptable success rates. These approaches include rapid exit from shelter for both families and single adults with serious mental illness, and community support strategies involving housing and services for people with serious mental illness exiting psychiatric and correctional facilities. The same strategies also appear useful in preventing first-time homelessness among people with serious mental illness.

References

Buckner, J. C. (2004). Impact of homelessness on children. In D. Levinson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of homelessness, Vol. 1 (pp. 74–76). Thousand Oaks, CA: Berkshire Publishing Group.

Burt, M. R., Aron, L. Y., & Lee, E. (2001). Helping America’s homeless: Emergency shelter or affordable housing? Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Burt, M. R., Hedderson, J., Zweig, J., Ortiz, M. J., Aron-Turnham, L., & Johnson, S. M. (2004). Strategies for reducing chronic street homelessness. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Burt, M. R., Pearson, C., & Montgomery, A. E. (2005). Strategies for preventing homelessness. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Culhane, D., Dejowski, E. F., Ibanez, J., Needham, E., & Maccia, I. (1994). Public shelter admission rates in Philadelphia and New York City: The implications of turnover rates for sheltered population counts. Housing Policy Debate, 5(2), 107–140.

Lindblom, E. (1996). Preventing homelessness. In J. Baumohl (Ed.), Homelessness in America (pp. 187–200). Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Link, B. G., Susser, E., Stueve, A., Phelan, J., Moore, R. E., & Struening, E. (1994). Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 84(12), 1907–1912.

Link, B. G., Susser, E., Stueve, A., Phelan, J., Moore, R. E., & Struening, E. (1995). Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States: New evidence on an old debate. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65(3), 347–354.

National Alliance to End Homelessness (2000). A plan not a dream: How to end homelessness in ten years. Retrieved August 10, 2006, from http://www.endhomelessness.org/pub/tenyear/10yearplan.pdf.

Quigley, J. M., Raphael, S., & Smolensky, E. (2001). The links between income inequality, housing markets, and homelessness in California. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.

Rog, D. J., McCombs-Thornton, K. L., Gilbert-Mongelli, A. M., Brito, M. C., & Holupka, C. S. (1995). Implementation of the Homeless Families Program: Characteristics, strengths, and needs of participant families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65(4), 514–527.

Shern, D. L., Felton, C. J., Hough, R. L., Lehman, A. F., Goldfinger, S. M., & Valencia, E., et al. (1997). Housing outcomes for homeless adults with mental illness: Results from the second-round McKinney Program. Psychiatric Services, 48(2), 239–241.

Shinn, M., Baumohl, J., & Hopper, K. (2001). The prevention of homelessness revisited. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 1(1), 95–127.

Shinn, M., & Weitzman, B. (1996). Homeless families are different. In J. Baumohl (Ed.), Homelessness in America (pp. 109–122). Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Shinn, M., Weitzman, B. C., Stojanovic, D., Knickman, J. R., Jimenez, I., & Duchon, L., et al. (1998). Predictors of homelessness among families in New York City: From shelter request to housing stability. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 1651–1657.

Stojanovic, D., Weitzman, B. C., Shinn, M., Labay, L. E., & Williams, N. P. (1999). Tracing the path out of homelessness: The housing patterns of families after exiting shelters. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 199–208.

Tsemberis, S., & Eisenberg, R. F. (2000). Pathways to Housing: Supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services, 51(4), 487–493.

Tsemberis, S., Gulchar, L., & Nakae, M. (2004). Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 651–656.

Weinreb, L., Gelberg, L., Arangua, L., & Sullivan, M. (2004). Disorders and health problems: Overview. In D. Levinson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Homelessness, Vol. 1 (pp. 115–123). Thousand Oaks, CA: Berkshire Publishing Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is based on a recent report to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development by Burt et al. (2005), Strategies for Preventing Homelessness. The report summarizes the findings and implications of a study the authors conducted for HUD (contract number GS-10F-0297L to Walter R. Macdonald Associates, Inc.); the present paper is a modified version of the report’s executive summary. The full report may be found at www.urban.org and at www.huduser.org

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Burt, M.R., Pearson, C. & Montgomery, A.E. Community-Wide Strategies for Preventing Homelessness: Recent Evidence. J Primary Prevent 28, 213–228 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-007-0094-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-007-0094-8