Abstract

A recent experimental literature shows that truth-telling is not always motivated by pecuniary motives, and several alternative motivations have been proposed. However, their relative importance in any given context is still not totally clear. This paper investigates the relevance of pure lie aversion, that is, a dislike for lies independent of their consequences. We propose a very simple design where other motives considered in the literature predict zero truth-telling, whereas pure lie aversion predicts a non-zero rate. Thus we interpret the finding that more than a third of the subjects tell the truth as evidence for pure lie aversion. Our design also prevents confounds with another motivation (a desire to act as others expect us to act) not frequently considered but consistent with much existing evidence. We also observe that subjects who tell the truth are more likely to believe that others will tell the truth as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We stress that the crucial difference between pure lie aversion and guilt aversion is that the latter posits a relation between beliefs and the activation of the bad feelings, whereas pure lie aversion assumes that the bad feelings are activated simply by uttering a lie. The name given to such feelings, in contrast, is largely immaterial for the distinction. Pure lie aversion does not rule out that the bad feelings are what psychologists call guilt.

Peeters et al. (2007) run an experiment with a sender-receiver game played over 100 rounds with re-matching, and analyze the performance of a model of ‘consequentialistic preferences’ with characteristics similar to what we denominate here belief-dependent lie aversion, and another of ‘deontological preferences’ similar to pure lie aversion. Although some results tend to lend weight to the idea of belief-dependent lie aversion, a test of such model in the repeated sender-receiver game is hindered by the fact that it predicts multiple equilibria. In the conclusion, we discuss how some of our results could help to understand dynamic play in repeated games like theirs.

This distinguishes our study from ‘deception games’ (e.g. Gneezy 2005), in which the receiver does not know the payoff set. In those studies, this ignorance eliminates the concern that the sender’s decision is influenced by his knowledge that the receiver knows whether the action was harmful, leaving the harm intact. In our study, this concern does not arise because the receiver is not harmed by the sender’s choice. Furthermore, the receiver’s knowledge of the sender’s incentives plays an integral part in the experimental treatments, as these incentives induce the expectations we attempt to manipulate with our (High and Low) treatments, described below.

This is relevant because, as we show elsewhere (López-Pérez and Spiegelman 2012), there is a correlation between honest behavior and the subject’s discipline. Since the distribution of disciplines is similar in both treatments, we can be sure that any potential difference in behavior across treatments is not due to differences in the subjects’ studies. Note also that there were not significant differences across treatments in the average values for political position (p=0.683; Mann-Whitney test), gender (p=0.452), or religiosity (p=0.165).

One could think of an alternative design in which the senders send messages to the experimenter, and hence there is no need for the receivers. In this case, however, belief-dependent lie aversion predicts that the subjects’ second order beliefs about the experimenter’s expectations should affect their decision. Controlling for such beliefs could be difficult. In addition, the degree (and relevance) of lie aversion could depend on the status of the recipient.

In principle, the strategy method might induce different behavior than the specific-response method, where participants know the realization of the signal. Yet a control treatment to check for possible effects of the strategy method showed no significant effect (the data is available in a web appendix at http://www.uam.es/raul.lopez). We also note that Brandts and Charness (2011) review the experimental studies that use both methods and find no treatment differences in most of them.

First-order (second-order) beliefs were paid only if the subject was later selected as a receiver (sender). We did this in order to avoid payoff asymmetries. Our belief-elicitation protocol is simple and rather easy to describe in instructions, and is not marred by any hedging problem.

If the cost of telling the truth was higher, many lie-averse types could decide not to tell the truth. We would be unable, therefore, to provide an accurate estimation of the percentage of subjects who dislike lies—i.e., of the relevance of pure lie aversion.

See the web appendix for a more detailed example.

Consider the function h(μ)=μ−μ⋅p B +(μ−1)⋅f(μ)p B . Given our assumptions, this function is continuous and such that h(0)<0; h(1)>0. The intermediate value theorem therefore implies the existence of some μ ∗ such that h(μ ∗)=0. Note also that uniqueness of μ ∗ is ensured for instance if h′>0, which imposes some restrictions on the distribution of Δ (we clarify this point further in the web appendix). If the distribution is such that uniqueness does not hold, we assume that individuals coordinate their beliefs on the highest μ ∗, so that prediction BDLA below is still satisfied.

We pool the data from the two waves of subjects (November 2010 and September–October 2011), as they are statistically identical in terms of their strategy choices. A Chi-square analysis of the joint distribution fails to reject independence (d.f.=3; stat=2.637; p-value=0.451).

None of the theories so far considered in this paper can explain why some small fractions of the subjects chose the payoff minimizing strategy (B, B) or the mythomaniac one (B, G) in both treatments. We discuss this issue later.

Similar tests also reveal that the two waves of subjects are identical on first-order expectations (p=0.838) and second-order expectations (p=0.990).

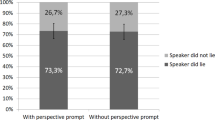

Note that the first percentage refers to the subjects choosing either (G, G) or (B, G), whereas the second one refers to the subjects playing either (G, B) or (B, B).

If this were true, our design could underestimate the relevance of pure lie aversion. In effect, some people could be lie-averse but lie in our experiment because they expect most others to lie as well.

There are two high-leverage outliers who report very low first- and very high second-order expectations. If these are removed, then the regression line is statistically indistinguishable from the 45-degree line.

Note: The instructions referred to the sender/receivers as type-A/type-B participants.

References

Battigalli, P., & Dufwenberg, M. (2007). Guilt in games. American Economic Review, 97(2), 170–176.

Battigalli, P., & Dufwenberg, M. (2009). Dynamic psychological games. Journal of Economic Theory, 144(1), 1–35.

Bicchieri, C. (2005). The grammar of society. London: Oxford University Press.

Bohnet, I., & Frey, B. (1999). Social distance and other regarding behavior in dictator games: comment. American Economic Review, 89, 335–339.

Brandts, J., & Charness, G. (2011). The strategy versus the direct-response method: a first survey of experimental comparisons. Experimental Economics, 14, 375–398.

Buchan, N. R., Johnson, E. J., & Croson, R. (2006). Let’s get personal: an international examination of the influence of communication, culture and social distance on other regarding preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60, 373–398.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2006). Promises and partnerships. Econometrica, 74(6), 1579–1601.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Monograph Supplement, 58(6), 1015–1026.

Dufwenberg, M., & Gneezy, U. (2000). Measuring beliefs in an experimental lost wallet game. Games and Economic Behavior, 30, 163–182.

Ellingsen, T., & Johannesson, M. (2004). Promises, threats, and fairness. Economic Journal, 114, 397–420.

Erat, S., & Gneezy, U. (2012). White lies. Management Science. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1110.1449.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Fischbacher, U., & Heusi, F. (2008). Lies in disguise: an experimental study on cheating. Mimeo.

Gneezy, U. (2005). Deception: the role of consequences. American Economic Review, 95(1), 384–394.

Hurkens, S., & Kartik, N. (2009). Would I lie to you? On social preferences and lying aversion. Experimental Economics, 12, 180–192.

Kartik, N. (2009). Strategic communication with lying costs. Review of Economic Studies, 76, 1359–1395.

López-Pérez, R. (2012). The power of words: a model of honesty and fairness. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33, 642–658.

López-Pérez, R., & Vorsatz, M. (2010). On approval and disapproval: theory and experiments. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31, 527–541.

López-Pérez, R., & Spiegelman, E. (2012). Do economists lie more? Mimeo.

Lundquist, T., Ellingsen, T., Gribbe, E., & Johannesson, M. (2009). The aversion to lying. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 70, 81–92.

Orbell, J., Dawes, R., & van de Kragt, A. (1990). The limits of multilateral promising. Ethics, 100, 616–627.

Peeters, R., Vorsatz, M., & Walzl, M. (2007). Truth, trust, and sanctions: on institutional selection in sender-receiver games. Mimeo.

Rosenthal, R. (2003). Covert communication in laboratories, classrooms, and the truly real world. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 151–154.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The false consensus effect: an egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 279–301.

Sánchez-Pagés, S., & Vorsatz, M. (2009). Enjoy the silence: an experiment on truth-telling. Experimental Economics, 12(2), 220–241.

Sommer, M., Rothmayr, C., Döhnel, K., Meinhardt, J., Schwerdtner, J., Sodian, B., & Hajak, G. (2010). How should I decide? The neural correlates of everyday moral reasoning. Neuropsychologia, 48, 2018–2026.

Sutter, M. (2009). Deception through telling the truth!? Experimental evidence from individuals and teams. Economic Journal, 119, 47–60.

Vanberg, C. (2008). Why do people keep their promises? An experimental test of two explanations. Econometrica, 76(6), 1467–1480.

Zak, P. J. (2011). Moral markets. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 77(2), 212–233.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are indebted to Matthieu Chemin, Joan Crespo, Bruno Deffains, Claude Fluet, Sean Horan, Hubert Kiss, Pierre Laserre, and Marc Vorsatz for helpful comments. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Education through the research project ECO2008-00510, and helpful research assistance by Sayoko Aketa and David Sánchez. Eli Spiegelman thanks Claude Fluet for guidance, encouragement and support.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

López-Pérez, R., Spiegelman, E. Why do people tell the truth? Experimental evidence for pure lie aversion. Exp Econ 16, 233–247 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9324-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9324-x