Abstract

Studies to confirm the effect of acknowledged prognostic markers in older breast cancer patients are scarce. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of HER-2 overexpression and PIK3CA mutations in older breast cancer patients. Female breast cancer patients aged 65 years or older, diagnosed between 1997 and 2004 in a geographical region in The Netherlands, with an invasive, non-metastatic tumour and tumour material available, were included in the study. The primary endpoint was relapse-free period and secondary endpoint was relative survival. Determinants were immunochemical HER-2 scores (0/1+, 2+ or 3+) and PIK3CA as a binary measure. Overall, 1698 patients were included, and 103 had a HER-2 score of 3+. HER-2 overexpression was associated with a higher recurrence risk (5 years recurrence risk 34 % vs. 12 %, adjusted p = 0.005), and a worse relative survival (10 years relative survival 48 % vs. 84 % for HER-2 negative; p = 0.004). PIK3CA mutations had no significant prognostic effect. We showed, in older breast cancer patients, that HER-2 overexpression was significantly associated with a worse outcome, but PIK3CA mutations had no prognostic effect. These results imply that older patients with HER-2 overexpressing breast cancer might benefit from additional targeted anti-HER-2 therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last decades an increased aged population in Western countries paralleled a marked increase in the incidence of age-related tumours, such as breast cancer [1]. In the United States of America, more than 40 % of the women diagnosed with breast cancer were 65 years of age or older in 2013 [2]. Due to the continuously increasing life expectancy, it is assumed that this number will further increase in the coming years.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) overexpression occurs in approximately 15–20 % of invasive breast carcinomas [3, 4]. Amplification of the HER-2 gene is associated with a more aggressive tumour phenotype [5], and if left untreated, is associated with worse clinical outcomes [6–9]. Detection of the amplification of this oncogene is widely performed and often routinely used in clinical settings [10], mainly for allocation of anti-HER-2 therapy, consisting of trastuzumab or pertuzumab in the (neo)adjuvant setting [11–16] and in the metastatic setting of lapatinib and trastuzumab emtansine [17, 18]. These anti-HER-2 therapies, in addition to cytotoxic chemotherapy, can result in a substantial reduction of recurrences, both in node-negative and node-positive breast cancer patients [19–21].

A well-known accomplice of HER-2 overexpression is the PIK3CA mutation, leading to aberrant activation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway, co-occurring in approximately 40 % of HER-2-amplified tumours where it supports tumour growth [22, 23]. The aberrant activation of the PI3K pathway correlates with reduced response to HER-2-directed therapies and accelerates HER-2-mediated breast epithelial transformation and metastatic progression [5, 24, 25]. In the younger population PI3K inhibitors are considered promising novel therapeutic modalities for the treatment of breast cancer.

An important shortcoming in current clinical breast cancer research is that the majority of studies are performed in a relatively young or fit elderly breast cancer population. This hampers the extrapolation of results of prognostic as well as therapeutic studies for older patients [26, 27].

The high incidence of cancer in the growing elderly population encourages to investigate the effect of potential prognostic and/or predictive markers in this population specifically. Some studies suggest that HER-2-positive breast cancer occurs less frequently in older patients [28, 29], but other studies fail to confirm this [30]. The clinical value of HER-2 overexpression and its treatment in the older population, well-known for competing clinical events, is not known. Because the accrual of older patients in clinical trials for anti-HER-2 therapy was poor, and an increased incidence of cardiac adverse events of trastuzumab was reported, its use is less widespread in older women than younger women [31]. However, evidence for the omission of anti-HER-2 therapy is lacking.

In summary, there are no conclusive data on the prognostic effect of HER-2 overexpression and PIK3CA mutations in the elderly breast cancer patient. Therefore, in order to restore the clinical interest of this neglected, but potentially very valuable treatment target for the elderly breast cancer patients, this study aims to elucidate the prognostic value of HER-2 overexpression, PIK3CA mutations and the interplay between these two markers in a population-based cohort of older breast cancer patients, that was not exposed to any anti-HER-2 therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients and tumours

For this study, patients with invasive, non-metastatic breast cancer from the FOCUS cohort (Female breast cancer in the elderly, Optimizing Clinical guidelines USing clinic-pathological and molecular data) who received surgery and had formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) intra-operative tumour samples available with successful measurements of the HER-2 status and/or PIK3CA mutations were included. The FOCUS cohort has been described extensively in previous publications [32]. Briefly, the cohort consists of all women aged ≥65 years at time of diagnosis, with invasive and in situ breast cancer, diagnosed between 1997 and 2004 in the South Western region of The Netherlands. Follow-up on survival status was available until the 1st of January 2013. All tumour samples were handled in a coded fashion, according to national ethical guidelines (“Code for Proper Secondary Use of Human Tissue”, Dutch Federation of Medical Scientific Societies).

Immunohistochemistry for HER-2

The immunohistochemical staining against HER-2 was performed on tissue sections of 4 μm from intra-operatively derived FFPE tumour material of the FOCUS cohort processed into a Tissue Micro Array (TMA) according to the previously described protocol [33]. Sections were incubated at room temperature with Polyclonal Rabbit Anti-Human c-erbB-2 Oncoprotein (DAKO, Denmark (A0485); 1:100, diluted in 1 % PBSA) for 20 min, followed by Envision anti-rabbit (DAKO, Denmark, Cytomation K4003) for 20 min. DAB was used for visualisation of positively stained breast tumour tissue on the TMA and counterstained with haematoxylin. All slides were stained simultaneously to avoid inter-assay variation. Strong c-erbB-2 Oncoprotein-positive brain tumour tissue served as positive and a negative control, the latter was obtained by omitting the primary antibody.

Evaluation of immunostaining

Microscopic quantification of the c-erbB-2 Oncoprotein was performed by two independent observers (C.E and A.M.). C-erbB-2 Oncoprotein was scored as follows: 0 for no staining at all or incomplete or faint/barely perceptible membrane staining in <10 % of the invasive tumour cells; 1+ for a faint/barely perceptible partial membrane staining in >10 % of the tumour cells; 2+ for weak to moderate complete membrane staining in >10 % of the tumour cells; 3+ for strong to complete membrane staining in >30 % of the tumour cells (Fig. 1). For all patients, the highest score out of the three punches of the same tumour was used for statistical analysis. If one or more punches were missing, the highest score of the remaining punch(es) was included for analyses.

PIK3CA mutation analysis

DNA was extracted from 2.0 mm diameter FFPE breast cancer tissue cores of 896 patients, using a fully automated system (Tissue Preparation System with VERSANT Tissue Preparation Reagents, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY, USA) as described previously [34]. Hydrolysis probe assays were performed for the major known mutations (hotspots) in exon 9, c.1624G > A; p.E542 K, c.1633G > A; p.E545 K and in exon 20 the c.3140A > G; p.H1047R as described before [35]. Hydrolysis probe assays were analysed using qPCR analysis software (CFX manager version 3/0, Bio-Rad). Mutation detection was performed by two observers (C.E. and R.E.) using DNA variant analysis software (Mutation Surveyor version 4.0.9, Softgenetics, State College, PA, USA). All primers and probes used for the assays are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical packages SPSS (version 20.0 for Windows, IBM SPSS statistics) and Stata SE 12.0.

The primary endpoint was Relapse-Free Period (RFP), defined as the time from date of diagnosis until any recurrence (any registered loco-regional recurrence, distant recurrence or contralateral breast cancer). The Cumulative Incidence Competing Risks method was used for calculating the cumulative incidence of recurrence, taking into account the competing risk of death [36]. Fine and Gray competing risks regression analyses were used for univariable and multivariable analysis for RFP, taking into account the competing risk of death without recurrence [37]. Multivariable analyses were adjusted for age, TNM stage, grade, oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) and type of breast surgery, axillary surgery, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy and chemotherapy (no anti-HER-2-therapy). Because the total follow-up time was longer than the follow-up time for RFP, the secondary endpoint was relative survival, calculated as the ratio between the observed survival in the cohort and the expected survival as calculated from the age-, sex- and year-matched background population [38]. Patients with missing data on the determinant of interest due to material handling were excluded from the statistical analyses regarding that determinant. First, it was checked if the patients with missing data had no significant survival difference from the patients without missing values, to confirm that there is no association with general prognosis.

Immunohistochemical HER-2 scores 0 and 1+ were considered HER-2 negative and HER-2 scores 2+ and 3 +were analysed as separate categories. In clinical practice, tumours with an immunohistochemical HER-2 score of 2+ are considered borderline positive, therefore, it is recommended to validate the immunohistochemical HER-2 2+ results using in situ hybridisation [39–41]. Unfortunately, it was not feasible to perform this additional test in our population. PIK3CA mutations were analysed as dichotomous variable (negative or positive) in all patients, and stratified for HER-2 status.

Results

Patient and tumour characteristics

A total of 1932 tumour blocks were available for immunohistochemical staining. After material handling and staining, 1698 patients were available for HER-2 analyses, and 912 patients for PIK3CA analyses. For the combined HER-2/PIK3CA analyses, 896 postmenopausal breast cancer patients were included in the analyses. The weighted kappa for the HER-2 immunohistochemistry was 0.78 (SE 0.03), indicative of good inter-observer agreement. There was no significant difference in overall survival between all patients from the original cohort (with or without tumour blocks available) and the patients with available data on respectively HER-2 or PIK3CA (Log Rank p = 0.537 and p = 0.298).

Patient, tumour and treatment characteristics are shown in Table 1 by HER-2 score. Overall, mean age at diagnosis was 76 years (standard deviation 7.2 years). The majority of patients presented with early stage breast cancer (stage I 34.5 %, stage II 51.5 %, stage III 11.5 %) of ductal morphology (75.3 %). In the majority of the patients a mastectomy (63.0 %) was performed. Merely six percent of patients were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (not including anti-HER-2-therapy). In this cohort, 78 % of the breast cancers were classified as HER-2 negative (N = 1326). Two hundred sixty-nine patients had a HER-2 score of 2+ (16 %), and 103 patients had a HER-2 score of 3+ (6 %). HER-2 overexpression was significantly associated with higher tumour grade (p < 0.001), ductal tumour morphology (p = 0.001), negative hormone receptor status (p < 0.001) and a higher Ki-67 proliferation rate (p < 0.001). In addition, HER-2 overexpression was associated with undergoing mastectomy rather than breast-conserving surgery (p = 0.007), less endocrine therapy (p = 0.008) and more chemotherapy (without anti-HER2 therapy) (p = 0.003).

Among all patients from whom PIK3CA status was available, 30 % had a PIK3CA mutation. In our data, PIK3CA mutations were not associated with HER-2 overexpression (p = 0.7).

Relapse-free period

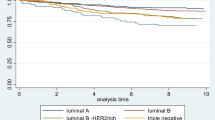

For RFP, median follow-up was 5.3 years (range 0–13.5 years). HER-2-negative patients had a cumulative recurrence risk of 12 % at 5 years, as compared to 12 % for patients with a HER-2 score of 2+ and 34 % for patients with a HER-2 score of 3+. In adjusted analysis, patients with a score of 2+ had an equal recurrence-free period at 5 years as compared to HER-2-negative patients (adjusted Sub-distribution Hazard Ratio (SHR) 0.95, 95 % Confidence Interval (CI) 0.67–1.35; p = 0.8), patients with a score of 3+ had significantly worse relapse-free period (adjusted SHR 1.81, 95 % CI 1.19–2.74; p = 0.005) (Table 2). Cumulative incidence curves are depicted in Fig. 2. Among patients without PIK3CA mutations, the cumulative incidence of recurrences at 5 years was 17 %, as compared to 16 % of patients with a PIK3CA mutation. There was no statistically significant difference in RFP between patients with and without a PIK3CA mutation (p = 0.2), also after stratifying for HER-2 status (Supplementary file 2).

Relative survival

Median follow-up was 8.9 years (range 0–17.0 years) for vital follow-up status. The results of the relative survival analyses are shown in Table 3. Patients with a HER-2 score of 2+, again showed an equal outcome as compared to the HER-2-negative patients (88 vs. 84 % at 10 years; multivariable Relative Excess Risk (RER) 0.78, 95 % CI 0.45–1.35; p = 0.4). Patients with a HER-2 score of 3+ had a significantly worse relative survival at 10 years (48 %; RER 2.07, 95 % CI 1.26–3.39; p = 0.004). Patients without PIK3CA mutations had a 10-year relative survival of 82 %, as compared to 81 % of patients with a PIK3CA mutation. There was no statistically significant difference in relative survival between patients with and without a PIK3CA mutation, also after stratifying for HER-2 status.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that HER-2 overexpression is of significant prognostic value in the older breast cancer population, even when taking the competing risk of mortality into account. Patients with HER-2 3+ tumours showed a significantly higher risk of recurrence, as compared to patients with a HER-2-negative tumour. Interestingly, patients with HER-2 2+ tumours had a similar recurrence risk as patients with HER-2 scores of 0 and 1+, who are considered to have HER-2-negative tumours. In this specific breast cancer population, PIK3CA mutations had no prognostic value.

With the results of this study, we identified a subgroup of older breast cancer patients with a significantly worse clinical outcome. Therefore, our results raise the hypothesis that women aged 65 and older with HER2 3+ tumours might benefit from additional therapy, which includes anti-HER-2 therapy. In contrast to the study performed by Syed et al., in which they claim a more indolent tumour character in the older breast cancer patient, we show that HER2+ positive tumours in the elderly are significantly associated with higher proliferative Ki67 presence in the tumour [42]. Our results could justify more aggressive anti-cancer treatment in the older breast cancer patients harbouring tumours with disadvantageous characteristics, as they, similar to their presence in the younger breast cancer patients, are associated with worse survival rates.

It is essential to realise that in the FOCUS cohort, it is very unlikely that patients received anti-HER-2 therapy, as the FDA approved trastuzumab for the treatment of breast cancer in 2006, and patients included in the FOCUS cohort were diagnosed and treated for their breast cancer between 1997 and 2004 [43]. Moreover, the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy was very low among the patients in our cohort, but is similar to previous observational studies in older breast cancer patients [44, 45].

An important question that still needs to be addressed is whether older breast cancer patients will benefit from anti-HER-2 therapy. Anti-HER-2 therapy is notorious for serious, mainly cardiac related, adverse events. However, recent studies have shown that cardiac adverse events from anti-HER-2 therapy are less severe and present with a lower incidence than initially assumed [21, 46, 47]. One of these studies was a side study of the HERA trial, in which the primary aim was to compare 1 versus 2 years of trastuzumab treatment. In this study, patients with a median follow-up of 8 years had a relatively low incidence of cardiac events (cumulative incidence of confirmed LVEF decrease was 7 % in the 2-year arm, 4 % in the 1-year arm and 1 % in the observation arm). Moreover, the majority (87 %) of HER-2 therapy-induced cardiac events appeared to be reversible after stopping trastuzumab treatment [47]. Chavez-MacGregor et al. showed that trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity did increase according to age. However, also in this older breast cancer population most of the cases were reversible, stressing the need for adequate monitoring [48]. It should also be noted that most (>80 %) of the older patients who initiate trastuzumab complete this therapy [49].

In current medical practice, anti-HER-2 therapy is frequently omitted from treatment options in older breast cancer patients. This is probably due to the current standards that advise the combination with chemotherapy, but also due to the fear of cardiac toxicity. One of the major characteristics of the older cancer population is the clinical heterogeneity among patients of the same chronological age. Therefore, merely taking into account chronological age may result in unfair survival chances due to under-treatment of fit elderly. Given the results of our current study, it could be suggested that the fit elderly breast cancer patient, especially when the Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) is acceptable (more than 50 %), should be treated with the same adjuvant regimen as the younger HER-2-positive breast cancer patients consisting of a taxane-based chemotherapy supplemented with 1 year of trastuzumab [41]. Moreover, older patients with less desirable clinical conditions, or when there is a strong preference to omit chemotherapy, dual HER-2 blockage (trastuzumab combined with pertuzumab) could be considered. In the neoadjuvant setting, such chemotherapy-free regimens have shown to be associated with very few side effects, but unfortunately also with a lower tumour response [46]. Currently, underrepresentation of elderly cancer patients in clinical trials hampers the implementation of widely agreed clinical practice recommendations, such as for HER-2 overexpressing breast cancer, which might result in under-treatment (suboptimal clinical outcome) or over-treatment (risk of significant toxicities) in the older breast cancer population. Currently, a randomised clinical trial is recruiting older (70+) patients with metastatic breast cancer disease, in which a chemotherapy-free regimen of trastuzumab and pertuzumab is compared with this combination and the addition of chemotherapy (EORTC-75111-10114) [50]. We believe that clinical trials focusing on such specific therapies can change clinical practice for this specific breast cancer population in the coming years, as finally more insight is provided about an often neglected but increasingly important subgroup of the breast cancer population. It is for this reason that the results of this trial are eagerly awaited.

In our study, no clinically prognostic value was retrieved from PIK3CA mutation analyses in the elderly, HER-2-positive or HER-2-negative breast cancer patients. Currently, it is believed that PIK3CA mutations in the co-occurrence of HER-2-positive breast disease result in poor prognosis [51]. In contrast, other studies have shown good prognosis with mutated PIK3CA in hormone receptor–positive tumours. The potential explanation of this finding is that continued activation of PI3K may have an inhibitory effect on HER-2 signalling [51]. Based on the results from our study, PIK3CA mutations might not have any prognostic value in the elderly breast cancer patient.

The major strength of our study is that we used the largest consecutive series of older breast cancer patients from a population-based cohort, from which tumour material was available. Therefore, our study is not affected by selection bias. Our study is unique because most previous prognostic studies on HER-2 expression are performed in a younger breast cancer population or as part of a clinical trial. It has been shown that older patients who are registered in a clinical trial have a significantly better overall health than patients of the same age in the general population [52]. Therefore, these studies cannot be simply extrapolated to the older breast cancer patients. This observation is in agreement with the American Cancer Society, which states that older patients (≥65 years) represent 45 % of all breast cancer cases and are a particularly vulnerable, and underrepresented patient group [53, 54]. Furthermore, recent articles by Chavez-MacGregor et al., and Vaz-Luis et al. [49, 53] point out that a relatively small portion of older breast cancer patients receive adjuvant chemotherapy (with/without trastuzumab therapy), which is attributed to under-treatment, a well-described phenomenon among the elderly in the USA, and also in Europe. Herewith urging the need for better identification of older patients who could benefit from anti-HER2 therapy through real-world information instead of selective clinical trials.

Our present study demonstrates that HER-2 overexpression is a strong and independent predictor of worse prognosis, tested in a representative population of older breast cancer patients and even after taking into account competing risk of mortality due to other reasons. Therefore, from an under-treatment point of view, the results of this study should convince oncologists that anti-HER2 therapy should be at least considered for every HER-2-positive patient, regardless of age.

A limitation of the study is that there was no tumour material available for all patients in the cohort, mostly due to logistical reasons. We minimised the chance that this selection affected our study aims, by ruling out the association of having missing values on the determinants of interest (HER-2 amplification and PIK3CA mutation) with overall mortality. Second, in contrast to clinical practice, no confirmatory in situ hybridisation was performed for the HER-2 2+ patients. However, based on the immunohistochemical data, the HER-2 2+ patients did not show a different clinical outcome compared to HER-2-negative patients. Based on these data, one could question the additional value of the costly in situ hybridisation in this specific subgroup of the older breast cancer population, as this group does not have a worse prognosis than the HER-2-negative patients.

In conclusion, this population-based study among elderly breast cancer patients showed a strong prognostic effect of HER-2 overexpression, defined as an immunohistochemical score of 3+, on higher recurrence risk as well as worse relative survival. Herewith, we defined a subgroup of older breast cancer patients who are at high risk for worse clinical outcome, with a strong likelihood of under-treatment. Future research should point out whether it is possible to establish an effective anti-HER-2 regimen with minimal toxicity for the elderly breast cancer population.

References

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 63:11–30

DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A (2014) Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 64:52–62

Ross JS, Fletcher JA (1998) The HER-2/neu oncogene in breast cancer: prognostic factor, predictive factor, and target for therapy. Stem Cells 16:413–428

Ross JS, Fletcher JA (1999) HER-2/neu (c-erb-B2) gene and protein in breast cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 112:S53–S67

Bartlett JM, Ellis IO, Dowsett M, Mallon EA, Cameron DA, Johnston S, Hall E, A’Hern R, Peckitt C, Bliss JM, Johnson L, Barrett-Lee P, Ellis P (2007) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status correlates with lymph node involvement in patients with estrogen receptor (ER) negative, but with grade in those with ER-positive early-stage breast cancer suitable for cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 25:4423–4430

Paik S, Hazan R, Fisher ER, Sass RE, Fisher B, Redmond C, Schlessinger J, Lippman ME, King CR (1990) Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project: prognostic significance of erbB-2 protein overexpression in primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 8:103–112

Tandon AK, Clark GM, Chamness GC, Ullrich A, McGuire WL (1989) HER-2/neu oncogene protein and prognosis in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 7:1120–1128

Wright C, Angus B, Nicholson S, Sainsbury JR, Cairns J, Gullick WJ, Kelly P, Harris AL, Horne CH (1989) Expression of c-erbB-2 oncoprotein: a prognostic indicator in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 49:2087–2090

Dawood S, Broglio K, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH (2010) Prognosis of women with metastatic breast cancer by HER2 status and trastuzumab treatment: an institutional-based review. J Clin Oncol 28:92–98

Hoff ER, Tubbs RR, Myles JL, Procop GW (2002) HER2/neu amplification in breast cancer: stratification by tumor type and grade. Am J Clin Pathol 117:916–921

Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, de Azambuja E, Procter M, Suter TM, Jackisch C, Cameron D, Weber HA, Heinzmann D, Dal LL, McFadden E, Dowsett M, Untch M, Gianni L, Bell R, Kohne CH, Vindevoghel A, Andersson M, Brunt AM, Otero-Reyes D, Song S, Smith I, Leyland-Jones B, Baselga J (2013) 2 years versus 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer (HERA): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 382:1021–1028

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, Baselga J, Norton L (2001) Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 344:783–792

Gianni L, Dafni U, Gelber RD, Azambuja E, Muehlbauer S, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Smith I, Baselga J, Jackisch C, Cameron D, Mano M, Pedrini JL, Veronesi A, Mendiola C, Pluzanska A, Semiglazov V, Vrdoljak E, Eckart MJ, Shen Z, Skiadopoulos G, Procter M, Pritchard KI, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Bell R (2011) Treatment with trastuzumab for 1 year after adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a 4-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 12:236–244

Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, Gralow JR, Kaufman PA, Visscher DW, Chen B, Ingle JN, Dakhil SR, Zujewski J, Moreno-Aspitia A, Pisansky TM, Jenkins RB (2011) Sequential versus concurrent trastuzumab in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:4491–4497

Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P, Alanko T, Kataja V, Asola R, Utriainen T, Kokko R, Hemminki A, Tarkkanen M, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Jyrkkio S, Flander M, Helle L, Ingalsuo S, Johansson K, Jaaskelainen AS, Pajunen M, Rauhala M, Kaleva-Kerola J, Salminen T, Leinonen M, Elomaa I, Isola J (2006) Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 354:809–820

Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, Roman L, Tseng LM, Liu MC, Lluch A, Staroslawska E, Haba-Rodriguez J, Im SA, Pedrini JL, Poirier B, Morandi P, Semiglazov V, Srimuninnimit V, Bianchi G, Szado T, Ratnayake J, Ross G, Valagussa P (2012) Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 13:25–32

Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Crown J, Chan A, Kaufman B, Skarlos D, Campone M, Davidson N, Berger M, Oliva C, Rubin SD, Stein S, Cameron D (2006) Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 355:2733–2743

Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, Krop IE, Welslau M, Baselga J, Pegram M, Oh DY, Dieras V, Guardino E, Fang L, Lu MW, Olsen S, Blackwell K (2012) Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 367:1783–1791

Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P, Alanko T, Kataja V, Asola R, Utriainen T, Kokko R, Hemminki A, Tarkkanen M, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Jyrkkio S, Flander M, Helle L, Ingalsuo S, Johansson K, Jaaskelainen AS, Pajunen M, Rauhala M, Kaleva-Kerola J, Salminen T, Leinonen M, Elomaa I, Isola J (2006) Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 354:809–820

Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer CE Jr, Davidson NE, Tan-Chiu E, Martino S, Paik S, Kaufman PA, Swain SM, Pisansky TM, Fehrenbacher L, Kutteh LA, Vogel VG, Visscher DW, Yothers G, Jenkins RB, Brown AM, Dakhil SR, Mamounas EP, Lingle WL, Klein PM, Ingle JN, Wolmark N (2005) Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353:1673–1684

Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Huovinen R, Jukkola-Vuorinen A, Tanner M, Kokko R, Ahlgren J, Auvinen P, Saarni O, Helle L, Villman K, Nyandoto P, Nilsson G, Leinonen M, Kataja V, Bono P, Lindman H (2014) Outcome of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with or without adjuvant trastuzumab in the Finland Capecitabine Trial (FinXX). Acta Oncol 53:186–194

Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490:61–70

Chakrabarty A, Rexer BN, Wang SE, Cook RS, Engelman JA, Arteaga CL (2010) H1047R phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mutant enhances HER2-mediated transformation by heregulin production and activation of HER3. Oncogene 29:5193–5203

Hanker AB, Pfefferle AD, Balko JM, Kuba MG, Young CD, Sanchez V, Sutton CR, Cheng H, Perou CM, Zhao JJ, Cook RS, Arteaga CL (2013) Mutant PIK3CA accelerates HER2-driven transgenic mammary tumors and induces resistance to combinations of anti-HER2 therapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:14372–14377

Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, Schneeweiss A, Paepke S, Lehmann A, Rezai M, Zahm DM, Sinn P, Khandan F, Eidtmann H, Dohnal K, Heinrichs C, Huober J, Pfitzner B, Fasching PA, Andre F, Lindner JL, Sotiriou C, Dykgers A, Guo S, Gade S, Nekljudova V, Loi S, Untch M, Denkert C (2014) PIK3CA mutations are associated with lower rates of pathologic complete response to anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) therapy in primary HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:312–3220

Crivellari D, Aapro M, Leonard R, von Minckwitz G, Brain E, Goldhirsch A, Veronesi A, Muss H (2007) Breast cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol 25:1882–1890

Yancik R (1997) Cancer burden in the aged: an epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer 80:1273–1283

Daidone MG, Coradini D, Martelli G, Veneroni S (2003) Primary breast cancer in elderly women: biological profile and relation with clinical outcome. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 45:313–325

Molino A, Giovannini M, Auriemma A, Fiorio E, Mercanti A, Mandara M, Caldara A, Micciolo R, Pavarana M, Cetto GL (2006) Pathological, biological and clinical characteristics, and surgical management, of elderly women with breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 59:226–233

Poltinnikov IM, Rudoler SB, Tymofyeyev Y, Kennedy J, Anne PR, Curran WJ Jr (2006) Impact of Her-2 Neu overexpression on outcome of elderly women treated with wide local excision and breast irradiation for early stage breast cancer: an exploratory analysis. Am J Clin Oncol 29:71–79

Albanell J, Ciruelos EM, Lluch A, Munoz M, Rodriguez CA (2014) Trastuzumab in small tumours and in elderly women. Cancer Treat Rev 40:41–47

de Glas NA, Kiderlen M, Bastiaannet E, de Craen AJ, van de Water W, van de Velde CJ, Liefers GJ (2013) Postoperative complications and survival of elderly breast cancer patients: a FOCUS study analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 138:561–569

de Kruijf EM, Sajet A, van Nes JG, Natanov R, Putter H, Smit VT, Liefers GJ, van den Elsen PJ, van de Velde CJ, Kuppen PJ (2010) HLA-E and HLA-G expression in classical HLA class I-negative tumors is of prognostic value for clinical outcome of early breast cancer patients. J Immunol 185:7452–7459

Van Eijk R, Stevens L, Morreau H, van Wezel T (2013) Assessment of a fully automated high-throughput DNA extraction method from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue for KRAS, and BRAF somatic mutation analysis. Exp Mol Pathol 94:121–125

Van Eijk R, Licht J, Schrumpf M, Talebian YM, Ruano D, Forte GI, Nederlof PM, Veselic M, Rabe KF, Annema JT, Smit V, Morreau H, van Wezel T (2011) Rapid KRAS, EGFR, BRAF and PIK3CA mutation analysis of fine needle aspirates from non-small-cell lung cancer using allele-specific qPCR. PLoS One 6:e17791

Verduijn M, Grootendorst DC, Dekker FW, Jager KJ, le Cessie S (2011) The analysis of competing events like cause-specific mortality—beware of the Kaplan-Meier method. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26:56–61

Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB (2007) Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med 26:2389–2430

Hakulinen T, Seppa K, Lambert PC (2011) Choosing the relative survival method for cancer survival estimation. Eur J Cancer 47:2202–2210

Akhdar A, Bronsard M, Lemieux R, Geha S (2011) HER-2 oncogene amplification assessment in invasive breast cancer by dual-color in situ hybridization (dc-CISH): a comparative study with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). Ann Pathol 31:472–479

Penault-Llorca F, Bilous M, Dowsett M, Hanna W, Osamura RY, Ruschoff J, van de Vijver M (2009) Emerging technologies for assessing HER2 amplification. Am J Clin Pathol 132:539–548

Dutch clinical guidelines for breast cancer (2012) Ref Type: Internet Communication

Syed BM, Green AR, Ellis IO, Cheung KL (2014) Human epidermal growth receptor-2 overexpressing early operable primary breast cancers in older (>/=70 years) women: biology and clinical outcome in comparison with younger (<70 years) patients. Ann Oncol 25:837–842

FDA approval of Trastuzumab (2014) Ref Type: Internet Communication

Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS (2006) Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:2750–2756

Louwman WJ, Vulto JC, Verhoeven RH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Coebergh JW, Voogd AC (2007) Clinical epidemiology of breast cancer in the elderly. Eur J Cancer 43:2242–2252

Nagayama A, Hayashida T, Jinno H, Takahashi M, Seki T, Matsumoto A, Murata T, Ashrafian H, Athanasiou T, Okabayashi K, Kitagawa Y (2014) Comparative effectiveness of neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer: a network meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju203

de Azambuja E, Procter MJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Agbor-Tarh D, Metzger-Filho O, Steinseifer J, Untch M, Smith IE, Gianni L, Baselga J, Jackisch C, Cameron DA, Bell R, Leyland-Jones B, Dowsett M, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Suter TM (2014) Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events at 8 years of median follow-up in the Herceptin Adjuvant trial (BIG 1-01). J Clin Oncol 32:2159–2165

Chavez-MacGregor M, Zhang N, Buchholz TA, Zhang Y, Niu J, Elting L, Smith BD, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH (2013) Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity among older patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31:4222–4228

Vaz-Luis I, Keating NL, Lin NU, Lii H, Winer EP, Freedman RA (2014) Duration and toxicity of adjuvant trastuzumab in older patients with early-stage breast cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 32:927–934

Clinicaltrials.gov, trial record NCT01597414, ASTER 2 study (2013) Ref Type: Internet Communication

Baselga J, Cortes J, Im SA, Clark E, Ross G, Kiermaier A, Swain SM (2014) Biomarker analyses in CLEOPATRA: a Phase III, placebo-controlled study of pertuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive, first-line metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:3753–3761

van de Water W, Kiderlen M, Bastiaannet E, Siesling S, Westendorp RG, van de Velde CJ, Nortier JW, Seynaeve C, de Craen AJ, Liefers GJ (2014) External validity of a trial comprised of elderly patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju051

Chavez-MacGregor M, Niu J, Zhang N, Elting LS, Smith BD, Banchs J, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH (2015) Cardiac monitoring during adjuvant trastuzumab-based chemotherapy among older patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 33:2176–2183

Takada M, Ishiguro H, Nagai S, Ohtani S, Kawabata H, Yanagita Y, Hozumi Y, Shimizu C, Takao S, Sato N, Kosaka Y, Sagara Y, Iwata H, Ohno S, Kuroi K, Masuda N, Yamashiro H, Sugimoto M, Kondo M, Naito Y, Sasano H, Inamoto T, Morita S, Toi M (2014) Survival of HER2-positive primary breast cancer patients treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus trastuzumab: a multicenter retrospective observational study (JBCRG-C03 study). Breast Cancer Res Treat 145:143–153

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Comprehensive Cancer Centre Netherlands (Leiden region), all participating hospitals and M. Murk-Jansen for data collection. This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Foundation (KWF 2007-3968), the sponsor had no role in the content of the study. None of the authors who contributed to this article have any financial or personal relationships with people or organisations that could inappropriately influence the data published.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Charla C. Engels and Mandy Kiderlen have contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Engels, C.C., Kiderlen, M., Bastiaannet, E. et al. The clinical value of HER-2 overexpression and PIK3CA mutations in the older breast cancer population: a FOCUS study analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 156, 361–370 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3734-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3734-y