Abstract

Obesity is well established as a cause of postmenopausal breast cancer incidence and mortality. In contrast, adiposity in early life reduces breast cancer incidence. However, whether short-term weight change influences breast cancer risk is not well known. We followed a cohort of 77,232 women from 1980 to 2006 (1,445,578 person-years), with routinely updated risk factor information, documenting 4196 incident cases of invasive breast cancer. ER and PR status were obtained from pathology reports and medical records yielding a total of 2033 ER+/PR+ tumors, 595 ER−/PR− tumors, 512 ER+/PR− tumors. The log incidence breast cancer model was used to assess the association of short-term weight gain (over past 4 years) while controlling for average BMI before and after menopause. Short-term weight change was significantly associated with breast cancer risk (RR 1.20; 95 % CI 1.09–1.33) for a 4-year weight gain of ≥15 lbs versus no change (≤5 lbs) (P_trend < 0.001). The association was stronger for premenopausal women (RR 1.38; 95 % CI 1.13–1.69) (P_trend = 0.004) than for postmenopausal women (RR 1.10; 95 % CI 0.97–1.25) (P_trend = 0.063). Short-term weight gain during premenopause had a stronger association for ER+/PR− (RR per 25 lb weight gain = 2.19; 95 % CI 1.33–3.61, P = 0.002) and ER−/PR− breast cancer (RR per 25 lb weight gain = 1.61; 95 % CI 1.09–2.38, P = 0.016) than for ER+/PR+ breast cancer (RR per 25 lb weight gain = 1.13; 95 % CI 0.89–1.43, P = 0.32). There are deleterious effects of short-term weight gain, particularly during pre-menopause, even after controlling for average BMI before and after menopause. The association was stronger for ER+/PR− and ER−/PR− than for ER+/PR+ breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Obesity is established as a cause of postmenopausal breast cancer incidence and mortality [1, 2]. Furthermore, adiposity in early life—through the premenopausal years—reduces breast cancer incidence [3, 4]. This was observed for adiposity at ages 5 and 10 [4]. The Carolina breast cancer study [5] shows this association in White but not Black women for premenopausal breast cancer. The French E3 N cohort [6] shows an inverse trend for larger body shape at age 8 that is not significant for premenopausal breast cancer though they had far fewer cases than in their postmenopausal women where the trend was significant Among premenopausal women body shape 4+ had HR 0.88 (0.79, 0.98) compared to the leanest women at age 8. Among postmenopausal women, the trend was significantly inverse for ER+ and significantly positive for ER−PR−. Slattery et al. [7] analyzing the New Mexico region case control study, using BMI at age 15, reported a strongly inverse association for girls with heavier figures but the trend was not significant. BMI at age 15 > 22.5 had an RR 0.68 (0.44, 1.04) for non-Hispanic white women, and 0.65 (0.39, 1.08) for Hispanic premenopausal breast cancer. Berstad et al. [8] used body shapes at menarche in their case control study. They report a significant inverse trend for postmenopausal but non-significant inverse trend for premenopausal breast cancer (based on 2089 cases with reported body figure at menarche). Weiderpass [9] has prospective data from Norway and Sweden with 733 invasive premenopausal breast cancers. Body shape at age 7 was used. They control for both BMI at 18 and adult BMI and reported inverse associations for heavier girls at age 7, though not a significant trend. These inverse associations persists across categories of BMI at cohort entry.

Studies using measures of adiposity at age 18 also report inverse relations with premenopausal breast cancer [10] and for some but not all molecular subtypes of breast cancer [11]. Prospective studies of weight gain from early adult years (ages 18–25) to mid-life, show positive associations with risk of postmenopausal breast cancer [12–20], and support the conclusion that long term adult weight gain increases risk of postmenopausal breast cancer [21]. However, Tamimi et al. [11] show significant heterogeneity of effects of weight gain since age 18 by histologic type. European data further suggested that weight gain in middle adulthood, over an average of 4.3 years, is related to subsequent risk of breast cancer over 7.5 years of follow-up. The association is stronger among women under age 50, though only 283 cases were premenopausal and diagnosed before age 50 [22]. Other studies of weight gain among women in their 40s have related weight gain to risk of postmenopausal breast cancer [12, 23], or have combined pre- and postmenopausal cases [24].

Although Nurses’ Health Study data show weight loss after menopause is related to reduced incidence of breast cancer [12], the temporal relation between childhood and adolescent weight, weight gain, and risk of breast cancer both before and after menopause is not well defined. The validated Rosner-Colditz breast cancer incidence model evaluates risk factors across the life course integrating exposures updated every 2 years, [25, 26]. This model, therefore, offers a unique opportunity to assess the relations of recent changes in weight, in relation to total pre- and postmenopausal invasive breast cancer, and subtype defined by receptor status while controlling for average BMI before and after menopause.

Methods

Methods of procedure and description of model

The Nurses’ Health Study was established in 1976 when 121, 701 female US registered nurses ages 30–55 responded to a mail questionnaire inquiring about risk factors for breast cancer including reproductive factors, hormone use, anthropometric variables, benign breast disease (BBD), and family history of breast cancer. The risk factors have been updated by questionnaires every 2 years up to the present time [27]. Alcohol consumption both currently and at age 18 was ascertained in 1980, updated in 1984, and every 4 years from 1986 to 2006. Weight at age 18 was ascertained in 1980. Hence, follow-up for this analysis began in 1980.

Identification of breast cancer cases

On each questionnaire, women were asked whether breast cancer had been diagnosed, and if so, the date of diagnosis. All women (or the next of kin, if deceased) were contacted for permission to review their medical records so as to confirm the diagnosis. Pathology reports were also reviewed to obtain information on estrogen (ER), and progesterone (PR) receptor status. Cases of invasive breast cancer from 1980–2006 were included in the primary analysis.

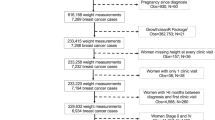

Cases for which we had a pathology report were included in these analyses. We excluded women with type of menopause other than natural or bilateral oophorectomy, prevalent cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer) in 1980, or missing data for weight at age 18, age at first birth, parity, age at menarche, age at menopause or hormone use. Thus, overall, 77,232 women were followed over 1,445,578 person-years from 1980 to 2006 during which 4196 incident invasive cases of breast cancer occurred. ER and PR status were obtained from pathology reports and medical records. A total of 2033 ER+/PR+, 595 ER−/PR−, and 512 ER+/PR− tumors were identified among women with complete breast cancer risk factor information. (See Online Resource 1 for breakdown by receptor type and menopausal status). 964 breast cancer cases with missing ER and/or PR status were censored at the time of diagnosis.

For the primary analysis (Tables 2, 3), all incident breast cancers were included including the 964 breast cancer cases with missing ER/PR subtype. For the tumor subtype analysis (Table 4) (e.g., for ER+/PR+ breast cancer), cases for other subtypes (e.g., ER+/PR− or ER−/PR− cases) or cases missing ER/PR subtypes were treated as censored events (i.e., competing risks). There were 92 women who developed ER−/PR+ breast cancer. These women were also considered as missing ER/PR status and censored at the time of diagnosis because in a subset of 71 women initially classified as ER−/PR+, only 4 (6 %) were confirmed as ER−/PR+ by TMA classification.

Statistical analysis

Description of the log-incidence model of breast cancer

We assume that the incidence of breast cancer at time t (I t ) is proportional to the number of cell divisions (C t ) accumulated up to age t (i.e., I t = KC t ). C t is obtained from

Thus, λ i = C i+1/C i = the rate of increase in C t from age i to age i + 1. Log (λ i ) is assumed to be a linear function of risk factors that are relevant at age i. The set of relevant risk factors and their magnitude and/or direction may vary by stage of reproductive life. Since the complete set of relevant risk factors at time t is unknown, we generalize Eq. 1 by substituting h 0(t) for k which allows for the existence of other risk factors which accumulate over time. The overall Cox regression model is given by

where h o(t) = baseline hazard.

Details of the model have been described elsewhere [25, 26, 28]. Two variables in the model that were controlled for in the present analyses were average BMI pre-menopause and average BMI post-menopause with the latter computed separately for person-time when a women was or was not on HRT. All variables in the model were updated every 2 years. The risk factors in Eq. 2 were updated every 2 years and analyzed as time-dependent covariates using the Cox proportional hazards model with an Anderson-Gill data structure.

To the model, we added terms for weight change over 4 years and then separately by menopausal status where women were premenopausal at both measures of weight, or postmenopausal at both measures of weight. 4-year weight change was updated at each questionnaire cycle (every 2 years) and used to predict breast cancer incidence over the next 2 years. Some women who were pre-menopausal over the 4-year weight change period may have become post-menopausal over the subsequent 2 years, but were included in the menopause-status-specific analyses.

Measures, weight, height, time of measure and validity or reproducibility

Self-reported weight in this cohort was shown to be strongly related to measured weight (r = 0.97) [29], with mean difference of (self-reported weight minus measured weight 6–12 months later = 1.5 kg) [30]. Validity of recalled weight at age 18 was assessed in younger nurses and compared against nursing school admission physical exam records showing a mean difference between self-report and recorded weights of 1.4 kg. The correlation between recalled and recorded weights was 0.87, and was independent of current age [31].

The correlations among weights are summarized in Online Resource 2. Weight at age 18 has a low correlation with long-term weight change among premenopausal (r = −0.11) and post-menopausal (r = −0.03) women. Short-term weight change was moderately correlated with long-term weight change for both pre-menopausal (r = 0.39) and postmenopausal (r = 0.52) women.

Menopausal status and post-menopausal hormone use

As reported previously [32], menopause is assessed on each follow-up questionnaire (http://www.channing.harvard.edu/nhs/questionnaires/index.shtml). A woman is asked, ‘‘Have your periods ceased permanently?’’ If yes, ‘‘Have you had either of your ovaries removed?’’ If yes, ‘‘How many remain (none; one)?’’ In the present analysis, person-time is only included for either pre-menopausal women or post-menopausal women with natural menopause or bilateral oophorectomy. Women with other types of menopause are censored at the time of menopause.

We defined the type of hormone therapy used on the basis of the response to follow-up questionnaires each 2 years. Women indicated that whether they used conjugated estrogens or progestin and, if so, the dose of estrogen and progestin used. They also indicated that whether they used hormones continuously or if they stopped estrogen for 7 days per month or used progestin for only 10–14 days per month or continuously.

Missing data issues

Weights for subjects that were missing at a specific questionnaire were carried forward from one previous questionnaire but were set to missing after this.

Model sequence

First, models were run for breast cancer on 4-year weight change overall (model 1, Table 2) after controlling for standard breast cancer risk factors. Second, we ran additional models with cross-product terms of 4-year weight change × menopausal status (models 2 and 3, Table 2) in addition to the main effect of menopausal status. Third, we subdivided post-menopausal women by postmenopausal hormone use status (PMH) at age t and t − 4 and introduced interaction terms of 4-year weight change by PMH (models 4 and 5, Table 2). Fourth, we explored whether the effect of weight change varied according to initial BMI at time t − 4 (<25/≥25) both overall and by menopausal status (Table 3). Fifth, we looked at whether effects of weight change varied by tumor subtype (ER+/PR+, ER+/PR−, ER−/PR−) (Table 4). In Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4, we controlled for long-term weight profiles using average BMI pre- and post-menopause in Eq. 2.

Results

Risk factors by weight change status (Table 1)

At the midpoint of follow-up (1994) the established risk factors for breast cancer varied modestly across categories of weight change (see Table 1). However, women with greater 4–year weight gain were on average younger, and more likely to be premenopausal (18 vs. 12 % among women with no weight change over 4 years).

Weight change over 4 years and incidence of breast cancer (Table 2)

We first fit weight change over 4 years to the full model adjusting for risk factors across the life course. Weight change is presented in categories of weight change and relative risks are compared to women with ≤5 lb change. Overall, the relative risk of breast cancer was 1.20 (95 % CI 1.09, 1.33) for women with ≥15 lb weight gain compared to women with no change. The overall mean 4-year weight change was 2.56 lb. The difference between the 10th and 90th percentiles for weight change was 25 pounds. The relative risk ofbreast cancer for this magnitude of weight gain in 4 years was 1.13 (95 % CI 1.06, 1.21).

We next assessed risk among women who were premenopausal and postmenopausal respectively at both time points (see Table 2, models 2 and 3). Among premenopausal women, mean weight gain = 4.59 lbs with 736 incident cases of breast cancer. The RR per 25 lbs weight gain was 1.26 (1.08, 1.48). Women who gained ≥15 lb in 4-years had a RR of 1.38 (1.13, 1.69) compared to women with no change. Among postmenopausal women, mean weight gain = 1.41 pounds. The RR per 25 lbs weight gain was 1.08 (1.00, 1.16); and the RR for a gain of ≥15 lb versus no change was 1.10 (0.97, 1.25). See Fig. 1. Associations with 4-year weight gain among postmenopausal women were similar for current and never postmenopausal hormone users (Table 2, models 4 and 5).

Weight gain and breast cancer risk stratified by baseline BMI (Table 3)

We next evaluated the association for weight gain by strata of baseline BMI (<25/≥25 kg/m2). Leaner women gained more weight than overweight and obese women. The overall association for weight gain was stronger among lean women (RR = 1.26 for 25 lb weight change) than among overweight and obese (RR = 1.09) phet = 0.04 (see Table 3). Among postmenopausal women, the association did not differ by baseline BMI. However, among premenopausal women the association for weight change over 4-years and breast cancer risk was significantly stronger among those who were normal weight at baseline (RR 1.65 vs. 1.02 for 25 lb weight change phet < 0.001) (see Fig. 2), and similarly for weight gain of ≥15 lb versus no change.

Weight change and tumor characteristics (Table 4)

We next assessed weight gain over 4 years and breast cancer defined by hormone receptor status (Table 4). This analysis included 3140 cases for whom receptor status was available. For the 2033 incident cases of ER+/PR+ breast cancer, weight gain showed an overall positive association (RR 1.10; 1.00, 1.20) for a 25 lb weight change. For women gaining ≥15 lb compared to those with no change the RR was 1.16 (1.00, 1.34). For ER+/PR− breast cancer, the overall association for a 25 lb change was stronger (1.36; 1.13, 1.64), p het = 0.04. The association was not different for the ER−/PR− cases (RR 1.09; 0.91, 1.31) compared to the ER+/PR+ association. Examining these associations among pre- and postmenopausal women separately, we observed that short-term weight gain during premenopause had a stronger association for ER+/PR− (RR per 25 lb weight gain = 2.19; 95 % CI 1.33–3.61, P = 0.002) and ER−/PR− breast cancer (RR per 25 lb weight gain = 1.61; 95 % CI 1.09–2.38, P = 0.016) than for ER+/PR+ breast cancer (RR per 25 lb weight gain = 1.13; 95 % CI 0.89–1.43, P = 0.32). Weight gain ≥15 lb showed a similar pattern. Among postmenopausal women, the strongest associations were observed for the ER+ PR− cases (RR 1.25; 1.01, 1.54) per 25 lb weight gain.

BMI

We repeated the analyses using BMI as the measure of change and results remained unchanged. Likewise, when using other analytic structures including Poisson regression, results were comparable.

Discussion

In these detailed prospective data with repeated measures of weight across the life course, weight gain over 4-years was positively associated with overall breast cancer risk, and was most strongly associated with premenopausal breast cancer. Short-term weight gain in premenopausal years also carries risk for ER+/PR− and ER−/PR− disease.

These data support a report from Mexico where trajectories of weight gain showed increased risk of premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer; increasing adiposity from age 8 was positively related to increased risk [33]. That study, however, did not have repeated measures and could not separate out short-term and long-term weight change. Other prospective studies have focused on long term or mid-life weight gain and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer [12–15, 24].

The current data confirm findings that reported from the EPIC-PANACEA study, which showed a positive relation between weight gain over an average of 4.3 years and risk for breast cancer during 7.5 years of follow-up [22]. EPIC had a weight gain in the top quintile of 1.33 kg/year, on average, representing a gain of approximately 11.7 pounds over 4 years, comparable to our category of 10–14.9 pounds. The association was stronger among women diagnosed under age 50. We have substantially more cases of premenopausal breast cancer and replicate that association. That study showed no heterogeneity according to receptor status among cases diagnosed after age 50. The EPIC results stratified by hormone therapy showed no modification of the association after age 50. Our results for short-term weight gain are consistent with this result. However, EPIC did not find a significant interaction between weight change and initial BMI (≤25 vs. >25) for either cases diagnosed at ≤50 or >50, contrary to our finding of a significant interaction for pre-menopausal women. However, the number of cases in EPIC diagnosed at ≤50 years with initial BMI >25 was small.

Other studies of premenopausal women have not focused on such short-term changes in weight. Zeigler et al. reported weight change over 10 years was directly related to increased risk of breast cancer for women in their 40s and 50s [34]. For women in their 40s and hence probably premenopausal, a 10-year weight gain of 26 or more pounds had a relative risk of 1.35 (0.65, 2.82) compared to no weight change. A recent case–control study of body size and breast cancer risk in pre and postmenopausal Black women assessed recalled change in BMI from 18 to 35 and reported inverse relations with premenopausal breast cancer [5].

Repeated assessments of weight area strength of this study. Drawing on these, we were able to model changes in weight across the life course and construct life course models that controlled for weight at different ages. Thus we separated out recent weight gain from adiposity at age 18 and adult weight gain. Furthermore, the effect of weight gain has been observed to vary by BMI and use of postmenopausal hormone therapy in previous studies [13], issues we could address with clarity in this analysis. We also show the adverse effect of short-term weight gain is stronger for premenopausal than postmenopausal breast cancer, and for ER+ PR− and ER−PR− breast cancer.

Of note, the previous report from the Nurses’ Health Study cohort of adiposity and weight gain in relation to postmenopausal breast cancer (as modified by use of hormones), showed that weight gain from age 18 analyzed through 2002 was more strongly related to risk among never users of postmenopausal hormones [12]. This is consistent with other studies, but we note that short-term weight gain in postmenopausal women is independent of prior long-term premenopausal weight gain (Online Resource 2).

Previous studies have related fasting glucose to risk of premenopausal breast cancer. The prospective ORDET study of women, showed a relative risk of 2.76 (1.18–6.46) for the top versus bottom quintile of fasting glucose and premenopausal breast cancer [35]. A meta-analysis of 10 cohort studies among non-diabetics reported significant increases in risk in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women for elevated glucose levels (>7.0 mml/L) [36]. Although the association of BMI with IGF-1 levels is non-linear, IGF-1 increases with adiposity among normal and overweight women, and is related to increased risk of premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer [37]. In postmenopausal women, BMI increases circulating estrogen levels, that in turn are associated with increased breast cancer risk; in contrast, in premenopausal women, BMI is generally inversely related to estrogens and estrogens are less clearly related to risk. These metabolic pathways provide plausible mechanisms for weight gain to increase breast cancer risk.

Weight in this cohort is self-reported but validation studies show it is highly correlated with independently measured weight [3, 38] and the mean difference of self-report and measured weight is minimal. Weight at age 18 is reproducibly reported with little bias [31]. Consistent with previous reports from our cohort, weight gain is greater in premenopausal women [39].

Conclusion

Short-term weight gain, particularly during premenopausal years and among normal weight women, adds to risk of breast cancer.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2002) Weight control and physical activity, vol 6. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ (2003) Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 348(17):1625–1638

Willett WC, Browne ML, Bain C, Lipnick RJ, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Colditz GA, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE (1985) Relative weight and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol 122:731–740

Baer HJ, Tworoger SS, Hankinson SE, Willett WC (2010) Body fatness at young ages and risk of breast cancer throughout life. Am J Epidemiol 171(11):1183–1194

Robinson WR, Tse CK, Olshan AF, Troester MA (2014) Body size across the life course and risk of premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer in Black women, the Carolina Breast Cancer Study, 1993–2001. Cancer Causes Control 25(9):1101–1117

Fagherazzi G, Guillas G, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Mesrine S (2013) Body shape throughout life and the risk for breast cancer at adulthood in the French E3 N cohort. Eur J Cancer Prev 22(1):29–37

Slattery ML, Sweeney C, Edwards S, Herrick J, Baumgartner K, Wolff R, Murtaugh M, Baumgartner R, Giuliano A, Byers T (2007) Body size, weight change, fat distribution and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 102(1):85–101

Berstad P, Coates RJ, Bernstein L, Folger SG, Malone KE, Marchbanks PA, Weiss LK, Liff JM, McDonald JA, Strom BL et al (2010) A case-control study of body mass index and breast cancer risk in white and African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19(6):1532–1544

Weiderpass E, Braaten T, Magnusson C, Kumle M, Vainio H, Lund E, Adami HO (2004) A prospective study of body size in different periods of life and risk of premenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13(7):1121–1127

Amadou A, Ferrari P, Muwonge R, Moskal A, Biessy C, Romieu I, Hainaut P (2013) Overweight, obesity and risk of premenopausal breast cancer according to ethnicity: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Obes Rev 14:665–678

Tamimi RM, Colditz GA, Hazra A, Baer HJ, Hankinson SE, Rosner B, Marotti J, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Collins LC (2012) Traditional breast cancer risk factors in relation to molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131(1):159–167

Eliassen AH, Colditz G, Rosner B, Willett W, Hankinson SE (2006) Adult weight change and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. JAMA 296:193–201

Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Willett WC (1997) Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. J Am Med Assoc (JAMA) 278(17):1407–1411

Morimoto LM, White E, Chen Z, Chlebowski RT, Hays J, Kuller L, Lopez AM, Manson J, Margolis KL, Muti PC et al (2002) Obesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative (United States). Cancer Causes Control 13(8):741–751

Feigelson HS, Jonas CR, Teras LR, Thun MJ, Calle EE (2004) Weight gain, body mass index, hormone replacement therapy, and postmenopausal breast cancer in a large prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13(2):220–224

Harvie M, Howell A, Vierkant RA, Kumar N, Cerhan JR, Kelemen LE, Folsom AR, Sellers TA (2005) Association of gain and loss of weight before and after menopause with risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in the Iowa women’s health study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14(3):656–661

Suzuki S, Kojima M, Tokudome S, Mori M, Sakauchi F, Wakai K, Fujino Y, Lin Y, Kikuchi S, Tamakoshi K et al (2013) Obesity/weight gain and breast cancer risk: findings from the Japan collaborative cohort study for the evaluation of cancer risk. J Epidemiol 23(2):139–145

Suzuki R, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Sawada N, Yamaji T, Shimazu T, Tsugane S (2011) Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study G: body weight at age 20 years, subsequent weight change and breast cancer risk defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status—the Japan public health center-based prospective study. Int J Cancer 129(5):1214–1224

Alsaker MD, Janszky I, Opdahl S, Vatten LJ, Romundstad PR (2013) Weight change in adulthood and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the HUNT study of Norway. Br J Cancer 109(5):1310–1317

Krishnan K, Bassett JK, MacInnis RJ, English DR, Hopper JL, McLean C, Giles GG, Baglietto L (2013) Associations between weight in early adulthood, change in weight, and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22(8):1409–1416

World Cancer Research Fund: Continuous Update Project (2010) Keeping the science current. Breast Cancer 2010 Report. In: Continous update project. American Institute for Cancer Research, Washington DC

Emaus MJ, van Gils CH, Bakker MF, Bisschop CN, Monninkhof EM, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Travier N, Berentzen TL, Overvad K, Tjonneland A et al (2014) Weight change in middle adulthood and breast cancer risk in the EPIC-PANACEA study. Int J Cancer 135:2887–2899

Radimer KL, Ballard-Barbash R, Miller JS, Fay MP, Schatzkin A, Troiano R, Kreger BE, Splansky GL (2004) Weight change and the risk of late-onset breast cancer in the original Framingham cohort. Nutr Cancer 49(1):7–13

Vrieling A, Buck K, Kaaks R, Chang-Claude J (2010) Adult weight gain in relation to breast cancer risk by estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 123(3):641–649

Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, Sullivan-Halley J, Lacey JV Jr, Bernstein L (2013) Validation of Rosner-Colditz breast cancer incidence model using an independent data set, the California Teachers Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 142(1):187–202

Rosner B, Colditz GA (1996) Nurses’ health study: log-incidence mathematical model of breast cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 88(6):359–364

Colditz GA, Hankinson SE (2005) The Nurses’ Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer 5(5):388–396

Rosner B, Glynn RJ, Tamimi RM, Chen WY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Hankinson SE (2013) Breast cancer risk prediction with heterogeneous risk profiles according to breast cancer tumor markers. Am J Epidemiol 178(2):296–308

Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC (1990) Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology 1(6):466–473

Willett W, Stampfer MJ, Bain C, Lipnick R, Speizer FE, Rosner B, Cramer D, Hennekens CH (1983) Cigarette smoking, relative weight, and menopause. Am J Epidemiol 117:651–658

Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (1995) The validity of recalled height and past weight among younger women. Int J Obesity 19:570–572

Rosner B, Colditz GA (2011) Age at menopause: imputing age at menopause for women with a hysterectomy with application to risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Ann Epidemiol 21(6):450–460

Amadou A, Torres Mejia G, Fagherazzi G, Ortega C, Angeles-Llerenas A, Chajes V, Biessy C, Sighoko D, Hainaut P, Romieu I (2014) Anthropometry, silhouette trajectory, and risk of breast cancer in Mexican women. Am J Prev Med 46(3 Suppl 1):S52–S64

Ziegler RG, Hoover RN, Nomura AMY, West DW, Wu AH, Pike MC, Lake AJ, Horn-Ross PL, Kolonel LN, Siiteri PK et al (1996) Relative weight, weight change, height, and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst 88:650–660

Muti P, Quattrin T, Grant BJ, Krogh V, Micheli A, Schunemann HJ, Ram M, Freudenheim JL, Sieri S, Trevisan M et al (2002) Fasting glucose is a risk factor for breast cancer: a prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11(11):1361–1368

Boyle P, Koechlin A, Pizot C, Boniol M, Robertson C, Mullie P, Bolli G, Rosenstock J, Autier P (2013) Blood glucose concentrations and breast cancer risk in women without diabetes: a meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr 52(5):1533–1540

Endogenous Hormones Breast Cancer Collaborative Group, Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, Roddam AW (2010) Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), IGF binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), and breast cancer risk: pooled individual data analysis of 17 prospective studies. Lancet Oncol 11(6):530–542

Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC (1990) Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology 1:466–473

Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, London SJ, Segal MR, Speizer FE (1990) Patterns of weight change and their relation to diet in a cohort of healthy women. Am J Clin Nutr 51(6):1100–1105

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institutes at the National Institutes of Health (U54 CA155626, U54 CA155435, U54 CA155496, and PO1 CA 087969). This study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Human Studies Committee. The funders have not participated in the conduct of this study. The authors would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts to declare with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosner, B., Eliassen, A.H., Toriola, A.T. et al. Short-term weight gain and breast cancer risk by hormone receptor classification among pre- and postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 150, 643–653 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3344-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3344-0