Abstract

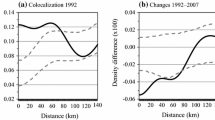

In this paper, we use distance-based methods, specifically a slight variation of Ripley’s K function and a bivariate generalisation of this function, to explore the detailed location pattern of the Spanish manufacturing industry, the scope of localisation and the tendency towards colocalisation between horizontally and vertically linked industries. To do so, we use micro-geographic data, considering a narrowly defined industry classification. Our results show heterogeneous location patterns, but with a significant tendency towards localisation. The sectoral scope is very sensitive to the degree of homogeneity of the activities in each sector. The more homogeneous the activities in a specific sector are, the more similarities we find in the spatial location patterns among its industries. Finally, although the patterns of colocalisation detected are sensitive to the counterfactuals used, between 20 and 48% of the pairs of industries with strong input–output linkages considered in this study show a significant tendency to colocalisation, and among them 74% are vertically linked industries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Duranton and Overman (2005), p. 1078.

See Ripley (1981).

SABI.

NACE 93—Rev. 1.

In some cases, this problem forced us to leave out some entire sectors, as is the case of Tobacco products (16), Coke, refined petroleum products (23), Office machinery and computers (30), and Recycling (37).

See “Appendix 2”.

Although K(r) can be estimated for any r, due to bias originated by border effects, it is common practice to consider only r < 25% of the length of the smallest side of the study area. See Dixon (2002).

In the empirical analysis, we use a polygonal shape as the area of study, A, in order to adjust the delimitation of this area as closely as possible. See “Appendix 3”.

These border-effect corrections should be incorporated to avoid artificial decreases in K(r) when r increases, because the increase in the area of the circle under consideration is not followed by the increase in firms (outside the study area there are no firms).

In each case, we generate 1000 simulations, rejecting the non-significant values by using a 95% confidence interval.

Given the properties of Ripley's K function, our measure of localisation is comparable across industries and unbiased with respect to scale and aggregation. Additionally, the construction of our confidence intervals gives an indication of the significance of the results, and control for industrial concentration and for the overall agglomeration of manufacturing. Thus, our approach satisfies the five essential requirements that Duranton and Overman (2005) stated that any test which measures concentration should fulfil.

This possibility is what Duranton and Overman (2005) have called ‘joint-localization’ and specifically say that ‘measuring co-localization and distinguishing from joint-localization is much more complex than analysing localization’.

When industries i and j belong to the same sector, we sampled the representative points of industry i at sites occupied by the remaining establishments in sector I, excluding sites occupied by establishments of industry j.

As in the previous case, we run 1000 simulations using Monte Carlo, rejecting the non-significant values by using a 95% confidence interval.

We also run 1000 simulations and use a 95% confidence interval to reject the non-significant values.

Duranton and Overman (2008), p. 239.

Information about the results for other industries is available upon request from the authors.

Specifically, the industries that show the most concentrated location patterns are (1730) Finishing of textiles, (1930) Manufacture of footwear, (2954) Manufacture of machinery for textile, apparel and leather production, (2211) Publishing of books, (2213) Publishing of journals and periodicals, (2442) Manufacture of pharmaceutical preparations, and (2630) Manufacture of ceramic tiles and flags.

Production and preserving of meat (1511), Production of meat and poultrymeat products (1513), Manufacture of machinery for food and beverage processing (2953); Saw milling and planing of wood, impregnation of wood (2010), Manufacture of builders’ carpentry and joinery (2030), Manufacture of agricultural and forestry machinery (2932).

See, for example, the two first industries in Table 1.

Manufacture of office and shop furniture (3612), Manufacture of kitchen furniture (3613), Manufacture of mattresses (3615), Manufacture of jewellery and related articles (3622), Manufacture of games and toys (3650).

The M TM estimated functions of all industries are available upon request from the authors.

This function becomes an appropriate instrument to detect clusters and their interaction, as long as the distance between these clusters is less than 2r, that is, one-half the shortest dimension of the study area (in our case around 400 km).

The Spanish Input–Output Tables are published by the National Institute of Statistics (INE), (http://www.ine.es/).

Given the large amount of information generated by this analysis, all the results are available upon request from the authors. Here, we will only present some examples and offer a detailed description of the overall behaviour of our analysis.

Of the 168 pairs of industries considered, approximately 50% are horizontally linked industries, and the other 50% are vertically linked industries.

The analysis is restricted to nineteen sectors due to the small number of establishments in the other four (16, 23, 30 and 37).

For example, Marcon and Puech (2003) did not analyse the whole of France, but instead an industrial area of 40 × 40 km around Paris and a larger rectangular area of France, measuring 550 × 630 km, and they explicitly said that it was impossible to use the whole of France because of border-effect corrections.

This software is downloadable from the following website: http://www.r-project.org/.

References

Albert JM, Casanova MR, Orts V (2012) Spatial location patterns of Spanish manufacturing firms. Pap Reg Sci 91(1):107–136

Alonso-Villar O, Chamorro-Rivas JM, González-Cerdeira X (2004) Agglomeration economies in manufacturing industries: the case of Spain. Appl Econ 36:2103–2116

Amiti M (1997) Specialisation patterns in Europe. Discussion paper 363, Centre for Economic Performance, London

Arbia G, Espa G, Quah D (2008) A class of spatial econometric methods in the empirical analysis of clusters of firms in the space. Empir Econ 34:81–103

Barlet M, Briant A, Crusson L (2013) Location patterns of service industries in France: a distance-based approach. Reg Sci Urban Econ 43(2):338–351

Behrens K, Bougna T (2015) An anatomy of the geographical concentration of Canadian manufacturing industries. Reg Sci Urban Econ 51:47–69

Brülhart M (2001) Evolving geographical concentration of European manufacturing industries. Weltwirtschaftliches Arch 137(2):215–243

Callejón M (1997) Concentración geográfica de la industria y economías de aglomeración. Econ Ind 317:61–68

De Dominicis L, Arbia G, De Groot HL (2007) The spatial distribution of economic activities in Italy. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper No. 07-094/3

Devereux MP, Griffith R, Simpson H (2004) The geographic distribution of production activity in the UK. Reg Sci Urban Econ 34:533–564

Dixon PM (2002) Ripley’s K function. Encycl Environ 3:1796–1803

Duranton G, Overman HG (2005) Testing for localization using micro-geographic data. Rev Econ Stud 72:1077–1106

Duranton G, Overman HG (2008) Exploring the detailed location patterns of UK manufacturing industries using microgeographic data. J Reg Sci 48(1):213–243

Ellison G, Glaeser E (1997) Geographic concentration in US manufacturing industries: a dartboard approach. J Polit Econ 105(5):889–927

Ellison G, Glaeser E, Kerr W (2010) What causes industry agglomeration? Evidence from coagglomeration patterns. Am Econ Rev 100:1195–1213

Fujita M, Krugman P, Venables AJ (1999) The spatial economy: cities, regions and international trade. MIT Press, Cambridge

Guimarães P, Figueiredo O, Woodward D (2011) Accounting for neighboring effects in measures of spatial concentration. J Reg Sci 51(4):678–693

Hoover EM (1948) The location of economic activity. McGraw Hill, New York

Koh HJ, Riedel N (2014) Assessing the localization pattern of German manufacturing and service industries: a distance-based approach. Reg Stud 48(5):823–843

Krugman P (1991a) Geography and trade. MIT Press, Cambridge

Krugman P (1991b) Increasing returns and economic geography. J Polit Econ 99(3):413–499

Marcon E, Puech F (2003) Evaluating the geographic concentration of industries using distance-based methods. J Econ Geogr 3(4):409–428

Marcon E, Puech F (2010) Measures of the geographic concentration of industries: improving distance-based methods. J Econ Geogr 10(5):745–762

Marshall A (1890) Principles of economics. MacMillan, London

Maurel F, Sédillot B (1999) A measure of the geographic concentration in French manufacturing industries. Reg Sci Urban Econ 29(5):575–604

Nakajima K, Saito YU, Uesugi I (2012) Measuring economic localization: evidence from Japanese firm-level data. J Jpn Int Econ 26(2):201–220

Ottaviano G, Puga D (1998) Agglomeration in the global economy: a survey of the ‘new economic geography’. World Econ 21:707–731

Puga D (1999) The rise and fall of regional inequalities. Eur Econ Rev 43(2):303–334

Puga D (2002) European regional policies in light of recent location theories. J Econ Geogr 2:373–406

Quah D, Simpson H (2003) Spatial cluster empirics. London School of Economics Working Paper Series

Ripley BD (1976) The second-order analysis of stationary point processes. J Appl Probab 13:255–266

Ripley BD (1977) Modelling spatial patterns. J R Stat Soc B (Methodol) 39:172–192

Ripley BD (1979) Test of ‘randomness’ for spatial patterns. J R Stat Soc B (Methodol) 41:368–374

Ripley BD (1981) Spatial statistics. Wiley, New York

Rosenthal SS, Strange WC (2001) The determinants of agglomeration. J Urban Econ 50(2):191–229

Venables AJ (1995) Economic integration and the location of firms. Am Econ Rev 85(2):296–300

Von Thünen J (1826) Der Isolierte Staad in Beziehung auf Landwirtschaft un NationalÄokonomie. Hamburg: Perthes. English translation: The isolated state. Oxford, Pergammon Press (1966)

Weber A (1909) Ueber den Standort der Industrien. Täubingen: J.C.B. Mohr. English translation: The Theory of the Location of Industries. Chicago University Press (1929)

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (ECO2014-58975-P) and Generalitat Valenciana (PROMETEOII/2014/054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 2.

Appendix 2

Spanish manufacturing activities are classified into 23 sectors according to ‘NACE 93—Rev. 1’:Footnote 33

-

(15) Food products and beverages

-

(16) Tobacco products

-

(17) Textiles

-

(18) Wearing apparel and dressing

-

(19) Tanning and dressing of leather

-

(20) Wood and products of wood

-

(21) Pulp, paper and paper products

-

(22) Publishing, printing and recorded media

-

(23) Coke, refined petroleum products

-

(24) Chemical and chemical products

-

(25) Rubber and plastic products

-

(26) Other non-metallic mineral products

-

(27) Basic metals

-

(28) Fabricated metal products

-

(29) Other machinery and equipment

-

(30) Office machinery and computers

-

(31) Electrical machinery

-

(32) Radio, televisions and other appliances

-

(33) Instruments

-

(34) Motor vehicles and trailers

-

(35) Other transport equipment

-

(36) Furniture and other products

-

(37) Recycling

Appendix 3

Currently, with existing computer equipment it is feasible to consider any arbitrary window A, albeit as complicated as a map of Spain. In our case, the statistical software application employed allows suitable border corrections to be applied to any irregular polygonal shape, thereby simplifying the treatment of border effects.

In Fig. 9, we can observe the polygonal shape that accurately delimits our territory and envelops the area of study. This allows us to avoid the nuisance of empty spaces where no establishments are found, which are represented by the space marked with oblique lines in the figure. This polygonal boundary was built by joining thirty-five points on the perimeter of the Spanish territory.

In previous works, a rectangular area was usually used due to the increasing complexity encountered when simulating random points inside the area and when correcting the border effects on convex shapes. These drawbacks thus limited the empirical analysis to rectangular areas.Footnote 34 In our case, the statistical software employed, ‘R’,Footnote 35 allows us to apply suitable border corrections to any irregular polygonal shape, thereby avoiding the shortcomings associated to the use of a rectangular area as the area of study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Casanova, M.R., Orts, V. & Albert, J.M. Sectoral scope and colocalisation of Spanish manufacturing industries. J Geogr Syst 19, 65–92 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-016-0242-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-016-0242-x

Keywords

- Spatial location

- Distance-based method

- Ripley’s K function

- Sectoral scope

- Colocalisation

- Vertical and horizontal linkages