Abstract

β-Amyloid (Aβ) related pathology shows a range of lesions which differ both qualitatively and quantitatively. Pathologists, to date, mainly focused on the assessment of both of these aspects but attempts to correlate the findings with clinical phenotypes are not convincing. It has been recently proposed in the same way as ι and α synuclein related lesions, also Aβ related pathology may follow a temporal evolution, i.e. distinct phases, characterized by a step-wise involvement of different brain-regions. Twenty-six independent observers reached an 81% absolute agreement while assessing the phase of Aβ, i.e. phase 1 = deposition of Aβ exclusively in neocortex, phase 2 = additionally in allocortex, phase 3 = additionally in diencephalon, phase 4 = additionally in brainstem, and phase 5 = additionally in cerebellum. These high agreement rates were reached when at least six brain regions were evaluated. Likewise, a high agreement (93%) was reached while assessing the absence/presence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and the type of CAA (74%) while examining the six brain regions. Of note, most of observers failed to detect capillary CAA when it was only mild and focal and thus instead of type 1, type 2 CAA was diagnosed. In conclusion, a reliable assessment of Aβ phase and presence/absence of CAA was achieved by a total of 26 observers who examined a standardized set of blocks taken from only six anatomical regions, applying commercially available reagents and by assessing them as instructed. Thus, one may consider rating of Aβ-phases as a diagnostic tool while analyzing subjects with suspected Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Because most of these blocks are currently routinely sampled by the majority of laboratories, assessment of the Aβ phase in AD is feasible even in large scale retrospective studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1984, Glenner and Wong purified and characterized a novel amyloid protein and in the same year they reported that patients with both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Down’s syndrome display this unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein that has been called β-amyloid (Aβ) protein [11, 12]. Later it became evident that the native precursor of this Aβ protein was a membrane associated protein [27]. Subsequently, numerous studies have examined postmortem brains and evaluated the Aβ seen in the parenchyma or vessel walls. Most often postmortem brain material obtained from aged or demented subjects suffering from clinically presumed AD has been investigated by applying immunohistochemical (IHC) methodology.

It has generally been considered sufficient to verify the existence of Aβ-immunoreactive (IR) aggregates in the parenchyma in only one or at the most few brain regions. When evaluating the severity of Aβ deposition in relation to clinical symptoms or the influence of various risk factors on the propensity towards Aβ-IR aggregation investigators have assessed the type of Aβ aggregates, i.e. diffuse versus dense, the number of aggregates or the extent of deposits by means of morphometry [3, 4, 17, 19]. One common finding in aged subjects is the presence of Aβ deposition in vessel walls, i.e. cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) [25] and this is also generally assessed during a neuropathological examination, particularly in subjects with haemorrhages [31]. In 2002, CAA was divided into two types: type 1—CAA is observed in capillaries with or without CAA in arteries and veins and type 2—CAA is detected in arteries and veins [28]. Interestingly, it has been claimed recently that in particular capillary CAA (type 1), is of significance for cognitive impairment probably by causing alterations in the cerebral blood flow as seen in mouse models for CAA and AD [7, 14, 30].

The assessment of Aβ in the parenchyma and in the vessel walls has thus become a part of the routine procedure while handling brains obtained from aged and particularly demented subjects. In 2008, a large inter-laboratory study reported that the agreement was poor while assessing the type (diffuse vs. dense) or the number of IHC detectable Aβ aggregates and the type of CAA, but instead good results could be achieved by applying a dichotomized strategy, i.e. assessment of the presence or absence of Aβ-IR deposits or CAA [6]. The most disturbing factor was that the above results were not significantly altered even when the same antibody provided good IHC staining [6]. The conclusion was that a more reliable and reproducible method is needed for the assessment of the severity of Aβ deposition and the type of CAA in inter-laboratory setting.

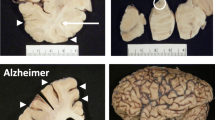

In 2002, Thal and colleagues reported that while analyzing 51 postmortem brains, a distinct pattern of involvement of brain regions with Aβ aggregates could be observed [29]. The regional involvement was divided into five phases, i.e. deposition of Aβ detected exclusively in neocortex was called phase 1, if additionally in allocortex it was phase 2, if also in diencephalon and striatum it was phase 3, if also in brainstem it was phase 4 and finally if also in cerebellum it was termed as phase 5. This stepwise involvement was considered to be typical for AD [29].

It was considered that in comparison to the assessment of the type or the density of Aβ-IR lesions, this kind of dichotomized analysis of Aβ-IR in various regions might yield reproducible results even in an inter-laboratory setting [6]. Furthermore, assessment of the regional distribution might be even more significant than previously appreciated. Recent studies have indicated that in subjects with the presenilin-1 mutation the Aβ deposition begins in striatum, i.e. it does not follow the above progression [16, 18]. In other studies, Aβ aggregates have been observed first in deep grey matter structures in dementia with Lewy bodies [2, 13, 24], Parkinson disease with dementia [15] and in subjects with stroke [1]. Thus, the assessment of the distribution of Aβ aggregates in a subject with AD related tauopathy might be more than relevant since any alteration from the expected pattern may reflect a genetic alteration or the existence of a significant concomitant disease process.

The objective of this study was to quantify inter-rater agreement of 26 neuropathologists who were asked to rate Aβ deposits in 34 cases by applying the strategy described by Thal and colleagues [29]. The agreement among observers while assessing CAA and in particular the type of CAA was also examined. A second objective was to identify any pitfalls that might have an impact on the agreement rates.

Materials and methods

The general working schedule is summarized in Fig. 1.

Sampling of material

Thirty-four cases were included and sampling of blocks was carried out by one neuropathologist (IA). Ten anatomical regions were included in this study: 1—cerebellar hemisphere, 2—midbrain with substantia nigra and central grey, 3—striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen) and insular cortex, 4—basal forebrain (with nucleus basalis of Meynert), amygdala and hypothalamus, 5—cingulated gyrus, 6—hippocampus at the level of lateral geniculate nucleus with CA regions, remnants of ento rhinal cortex and temporo-occipital cortex, 7—occipital cortex, visual cortex including calcarine fissure, 8—temporal cortex, superior and middle temporal gyrus, 9—parietal cortex, Brodmann area 39/40 and 10-frontal cortex, Brodmann area 9. In all of the examined cases Aβ-IR deposits were detected.

A total of five sets of 7 μm-thick sections were produced from all ten brain areas of the 34 cases. The description of these cases is provided in Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry

Five sets of the ten sampled sections were manually stained by applying IHC methodology. In brief, after rehydration, one set was pre-treated with 80% formic acid for 6 h and four sets for 1 h. All five sets were subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with a monoclonal primary antibody directed against Aβ. The first set with an antibody from Dako, clone 6F/3D, dilution 1:100 (Box 1) and four sets with an antibody from Signet, clone 4G8, dilution 1:2000 (Box 2-5). The reaction product was visualized using the Power vision detection system (ImmunoVision Technologies Co., MA, USA) with the use of Biosource Romulin AEC as the chromogen (Biocare medical, Walnut Creek, CA, USA).

The members of the reference group (IA, DRT, TA, ND, HK) jointly re-assessed all cases around a multi-headed microscope. The reference group assigned each case a phase of Aβ deposition and stated whether or not CAA and capillary CAA could be seen (Table 1) [28, 29]. Furthermore, the results obtained with the two different antibodies were compared.

Detailed assessment instructions were written by the reference group. The instructions included a description of the samples, pictures of the pathology that was present and expected to be assessed (Figs. 2, 3, 4), general instructions regarding assessment (Table 2) and tabulated guidelines (Table 3) on how to designate an Aβ phase. Furthermore, each participant was urged to read the original publications on which the assessment procedure was based [28, 29].

Various amyloid-β aggregates i.e. plaques, seen here in brown colour. Fleecy and diffuse (a–e), subpial band-like (f–h), perivascular lake-like (i) perivascular amyloid-β aggregates that are associated with amyloid angiopathy (j) and diffuse or dense plaques of various sizes and shapes (k–o). Magnification ×400, scale bar 10 μm

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Mild (a, b) and moderate (c) involvement of leptomeningeal arteries and veins. Primarily arterial and venous (d–h) and primarily capillary (i, j) CAA in the parenchyma (examples of capillary CAA marked with arrows). Note that parenchymal aggregates i.e. plaques are also seen (d–h). Magnification ×400, scale bar 10 μm

BNE participant efforts

Twenty-six participants assessed each case as instructed, thus each box of five produced sets was assessed by five to six examiners. The results were recorded on sheets (Table 4) which were sent to the coordinating centre. At the coordination centre, all data found in the assessment sheets was collected into one file (MP). These sheets included information on whether or not the participant had identified the required neuroanatomical regions, whether or not Aβ-IR, Aβ-IR plaques, CAA and capillary CAA had been observed and the designated Aβ phase and CAA type of the case. In addition, each participant stated whether or not the distribution of the pathology seemed to progress as expected, i.e. whether it was a typical or an atypical case.

Consensus meeting and joint assessment

A joint assessment of all IHC labelled sections was carried out around a multi-headed microscope. The diagnostic features of each stage were discussed. While studying the stained sections under the multi-headed microscope, the actual observations were compared with the filed results that had been collected from the original sheets. Inconsistencies in these observations were discussed and pitfalls were identified.

Analysis of the obtained data

At the coordinating centre, the data found in the assessment sheet was re-evaluated. With respect to CAA the results were calculated if only one or some of the sections had been included. Likewise, the influence of a reduction in the number of brain regions provided on the designation of the Aβ phase was analyzed. These calculations were carried out in order to determine the minimum number of neuroanatomical regions required to be assessed in order to achieve the desired result.

Photomicrograph

Digital images were taken using a Leica DM4000 B microscope equipped with a Leica DFC 320 digital camera.

Results

The results when 26 neuropathologists/observers assessed the IHC stained sections of the 34 cases by adhering to the given instructions are summarized in Tables 5 and 6.

The assigned phase while assessing the sections applying clone 6F3D did not differ from the results obtained with clone 4G8. There was only one case in phase 2 (case 4) and this case was unfortunately not optimal. According to the reference group, case four (Table 1) fulfilled phase 2 criteria in one stained set while applying clone 4G8 (absolute agreement 67%) whereas in the remaining 4 sets, the pathology was seen regionally to such an extent that only phase 1 criteria were fulfilled (absolute agreement 76%). Thus the only phase 2 case has been omitted from Table 5.

Aβ-IR pathology was seen by most raters in all cases. In one case which had been designated as phase 1 by the reference group, two assessors failed to detect any Aβ-IR pathology. The overall agreement while assigning the phase of Aβ deposition in 34 cases was 81% (when case 4 was excluded the value rose to 84%) while assessing all of the ten neuroanatomical regions (Table 5). Most of the cases were considered as being typical, i.e. at least one of the regions required for designation of that phase was affected.

Most of the evaluators participated in the consensus meeting where a joint assessment of the stained sections under a multi-headed microscope and the previous results obtained from the assessors were scrutinized. The group as a whole concluded that all cases were indeed in the phase designated by the reference group.

When assessing the individual results, it was noted that only some of the neuroanatomical regions were required in order to reach a reliable result (Table 6). In all three cases in phase 1, frontal, occipital or temporo-occipital cortices were assessed by most observers as being affected (absolute agreement 84%), in eight cases in phase 3, remnants of ento rhinal cortex (phase 2) and amygdaloid nucleus and nucleus basalis of Meynert (phase 3) were repeatedly affected (absolute agreement 80%).

The agreement while assessing CAA in all ten included sections was as high as 96% (Table 6). Likewise, the agreement was high while assessing leptomeningeal versus parenchymal involvement whereas slightly less harmony was obtained while classifying the type of CAA. There were 16 cases that displayed capillary CAA according to the reference group and this assessment result was verified at the joint assessment session around the multi-headed microscope. In six of the cases (cases 9, 11, 21, 27, 28 and 29), most of the 26 assessors had assigned the case as being of type 2, i.e. no capillary involvement was noted. In all of these cases only few affected capillaries were detected in one or two regions (hippocampus and or occipital cortex). The agreement rates did not change significantly when the number of blocks to be assessed was reduced, though the overall results were significantly different. The overall detection of CAA dropped from 28 to 22 cases, CAA in parenchyma from 24 to 16 cases and the number of cases with type 1 CAA, from 10 to 7 cases (Table 7). The results while assessing CAA in three brain regions, i.e. frontal and occipital cortices and hippocampus [8] or in the six regions selected above were almost the same as those obtained while assessing all ten original blocks.

Discussion

While rating the regional distribution of Aβ-IR, i.e. the phase of Aβ, an 81% agreement was reached when 26 neuropathologists assessed 34 cases all of which displayed Aβ-IR pathology. The agreement increased to 84%, when one case, that in most assessment sets displayed phase 1 and in one set phase 2, was excluded. By following the instructions that were based on the original publication by Thal and colleagues an agreement from 74 up to 90% could be achieved by assessing all ten included brain sections [29]. The lack of a phase 2 case even after a systematic search from a large original sample was unfortunate however; this might indicate that this phase is quite unusual or perhaps even virtually non-existent. Only a systematic assessment of forthcoming cases will resolve this issue.

Interestingly, similar agreement rates and assessment results were obtained when the number of blocks was reduced to six. It is noteworthy that these blocks are the same that are commonly sampled while working with brain specimens that have to be evaluated either due to the high age of the deceased or due to an age related neurodegenerative disorder. The hippocampal section and occipital cortex are assessed when dealing with AD-related tauopathy, basal forebrain section is evaluated when dealing with tauopathies and especially when one needs to deal with synucleinopathy, the midbrain section is examined when dealing with synucleinopathy, the section obtained from frontal cortex is assessed when dealing with TAR DNA binding protein (TDP-43) related pathology and finally cerebellum is evaluated when there is a suspicion of spinocerebellar ataxias [5, 9, 10, 20–23, 26]. Thus, these six brain sections are probably sampled in all laboratories during a routine neuropathological evaluation and consequently the proposed assessment of Aβ phase is quite feasible.

The high agreement here was also related to the fact that the assessors only had to evaluate the absence or presence of Aβ-IR pathology and thus the results were not influenced by the previously reported variability in the assessment of the extent of the pathology [6].

The agreement rates with respect to CAA were also high. Almost all, 96% of observers noted vascular involvement in the 28 cases in the same way as originally characterized by the reference group and confirmed in the joint assessment carried out around a multi-headed microscope. This result was not altered when only six blocks were selected.

The agreement was close to 80% in the classification of the type of CAA, i.e. 76% of assessors had seen capillary involvement in ten of the included cases. It is noteworthy that in six cases, most of the observers had failed to detect capillary CAA and only arterial and/or venous involvement was registered. In all of these cases, only a few capillaries in one or two regions were involved. This result emphasises that mild capillary involvement even after assessing numerous brain regions might easily be overlooked. The reliable assessment of capillary CAA is of particular importance in subjects with dementia lacking any other pathological alterations that can be considered as causative with respect to the clinical syndrome.

Here we noted that when only one cortical region was assessed, the agreement rates dropped marginally but more importantly the detection of CAA and particularly capillary CAA did change significantly, declining from 10 to 7 cases. Capillary CAA in one brain region has been assessed by Attems and Jellinger in 2004 [7] and by Jeynes and Provias in 2006 [14]. Both groups reported a significant correlation between capillary CAA and AD lesions. Based on our results, the strong association between AD lesions and capillary CAA should probably be re-evaluated including a larger number of regions. In 2008, Attems and colleagues reported a low prevalence of intracerebral haemorrhage in sporadic CAA when they assessed CAA in frontal and occipital cortices and also hippocampus [8]. While applying their strategy, including these three brain areas in the assessment, all 28 subjects with CAA were identified and in nine out of ten cases type 1 CAA was detected by most of the observers. Thus, by assessing these three blocks essentially equivalent results can be achieved as by assessing all ten blocks.

In epidemiological studies, one may need to assess huge sample sizes, e.g. thousands of cases. This is also the case when searching for risk genes. In both situations, material obtained from several laboratories will need to be combined. Furthermore, not only numerous samples need to be evaluated but they also have to be reliably and reproducibly characterized. Here we report that a high agreement can be achieved while assessing the regional distribution of Aβ-IR pathology and the absence/presence of CAA. With respect of capillary CAA, it should be borne in mind that a mild focal capillary CAA might be overlooked whereas in those cases where there is moderate involvement, the agreement regarding the detection of type 1 CAA is rather high. This reliable assessment of Aβ phase, presence/absence of CAA and type 1 CAA was reached by staining a standardized set of blocks taken from six neuroanatomical regions and by applying a commercially available reagent. The investigators were requested to follow written instructions. It is noteworthy that most of the blocks included here are currently routinely sampled by the majority of laboratories and thus even large scale retrospective studies could be organized. Therefore, determination of the phase of Aβ-deposition may represent a reliable and reproducible tool to describe and quantify AD related Aβ pathology in post-mortem brain specimens.

References

Aho L, Jolkkonen J, Alafuzoff I (2006) β-Amyloid aggregation in human brains with cerebrovascular lesions. Stroke 37:2940–2945

Aho L, Parkkinen L, Pirttilä T, Alafuzoff I (2008) Systematic appraisal using immunohistochemistry of brain pathology in aged and demented subjects. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25:423–432

Alafuzoff I, Helisalmi S, Mannermaa A, Riekkinen P Sr, Soininen H (1999) β-Amyloid load is not influenced by the severity of cardiovascular disease in aged and demented patients. Stroke 30:613–618

Alafuzoff I, Aho L, Helisalmi S, Mannermaa A, Soininen H (2009) β amyloid deposition in brains in subjects with diabetes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 35:60–68. doi:10.1111/j.1365-29990.2008.00948.x

Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Al-Sarraj S et al (2008) Staging of neurofibrillary Pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: a study of the BrainNet Europe consortium. Brain Pathol 18:484–496

Alafuzoff I, Pikkarainen M, Arzberger T et al (2008) Inter-laboratory comparison of neuropathological assessments of β-amyloid protein: a study of the BrainNet Europe consortium. Acta Neuropathol 115:533–546

Attems J, Jellinger K (2004) Only cerebral capillary amyloid angiopathy correlates with Alzheimer pathology—a pilot study. Acta Neuropathol 107:83–90

Attems J, Lauda F, Jellinger KA (2008) Unexpectedly low prevalence of intracerebral hemorrhages in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. An autopsy study. J Neurol 255:70–76

Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E (2003) Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24:197–211

Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K (2006) Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using routine sections and immunohistochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 112:389–404

Glenner GG, Wong CW (1984) Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 16:885–890

Glenner GG, Wong CW (1984) Alzheimer’s disease and Downs’ syndrome; sharing of a unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 16:1131–1135

Jellinger KA, Attems J (2006) Does striatal pathology distinguish Parkinson’s disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies? Acta Neuropathol 112:253–260

Jeynes B, Provias J (2006) The possible rope of capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s lesion development: a regional comparison. Acta Neuropathol 112:417–427

Kalaitzakis ME, Graeber MB, Gentleman SM, Pearce RK (2008) Striatal beta-amyloid deposition in Parkinson disease with dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 67:155–161

Klunk WE, Price JC, Mathis CA et al (2007) Amyloid deposition begins in striatum in presenilin-1 mutation carriers from two unrelated pedigrees. J Neurosci 27:6174–6184

Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A et al (2003) Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropath Exp Neurology 62:1087–1095

Koivunen J, Verkkoniemi A, Aalto S et al (2008) PET amyloid ligand [11C]PIB uptake shows predominantly striatal increase in variant Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 131:1845–1853

Kraszpulski M, Soininen H, Helisalmi S, Alafuzoff I (2001) The load and distribution of β-amyloid in brain tissue of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand 103:88–92

Leverenz JB, Hamilton R, Tsuang DW et al (2008) Empiric refinement of the pathologic assessment of Lewy-related pathology in the dementia patients. Brain Pathol 18:220–224

Mackenzie IR, Baborie A, Pickering-Brown S et al (2006) Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol 112:539–549

McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J et al (2005) Consortium on DLB Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 65:1863–1872

Müller CM, de Vos RAI, Maurage C-A, Thal DR, Tolnay M, Braak H (2005) Staging of Parkinson disease-related α-synuclein pathology: inter- and intra-rater reliability. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 64:623–628

Parkkinen L, Pirttilä T, Tervahauta M, Alafuzoff I (2005) Widespread and abundant α-synuclein pathology in a neurologically unimpaired subject. Neuropathology 25:304–314

Revesz T, Ghiso J, Lashley T et al (2003) Cerebral amyloid angiopathies: a pathologic, biochemical and genetic view. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 62:885–898

Sampathu DM, Neumann M, Kwong LK et al (2006) Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol 169:1343–1352

Selkoe DJ (1989) The deposition of amyloid protein in the aging mammalian brain: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Med 121:73–76

Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Yamaguchi H, del Tredici K, Braak H (2002) Two types of sporadic amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropath Exp Neurol 61:282–293

Thal RD, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H (2002) Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 58:1791–1800

Thal DR, Capetillo-Zarate E, Larionov S, Staufenbiel M, Zurbruegg S, Beckmann N (2008) Capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy is associated with vessel occlusion and cerebral blood flow disturbances. Neurobiol Aging. doi:10.1016/j.2008.01.017

Vonsattel JPG, Myers RH, Hedley-Whyte T, Ropper AH, Bird ED, Richardson EP (1991) Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy without and with hemorrhages: a comparative histological study. Ann Neurol 30:637–649

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Tarja Kauppinen, Mrs Merja Fali, Mr Heikki Luukkonen and Mr Hannu Tiainen for technical assistance. This study was supported by European Union grant FP6: BNEII No LSHM-CT-2004-503039. This article reflects only the authors’ views and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Kuopio University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Alafuzoff, I., Thal, D.R., Arzberger, T. et al. Assessment of β-amyloid deposits in human brain: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Acta Neuropathol 117, 309–320 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-009-0485-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-009-0485-4