Abstract

Objective

To describe the variability in rheumatology visits and referrals to other medical specialties of patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA) and to explore factors that may influence such variability.

Methods

Nation-wide cross-sectional study performed in 2009–2010. Randomly selected records of patients with a diagnosis of SpA and at least one visit to a rheumatology unit within the previous 2 years were audited. The rates of rheumatology visits and of referrals to other medical specialties were estimated—total and between centres—in the study period. Multilevel regression was used to analyse factors associated with variability and to adjust for clinical and patient characteristics.

Results

1168 patients’ records (45 centres) were reviewed, mainly ankylosing spondylitis (55.2 %) and psoriatic arthritis (22.2 %). The patients had incurred in 5908 visits to rheumatology clinics (rate 254 per 100 patient-years), 4307 visits to other medical specialties (19.6 % were referrals from rheumatology), and 775 visits to specialised nurse clinics. An adjusted variability in frequenting rheumatology clinics of 15.7 % between centres was observed. This was partially explained by the number of faculties and trainees. The adjusted intercentre variability for referrals to other specialties was 12.3 %, and it was associated with urban settings, number of procedures, and existence of SpA dedicated clinics; the probability of a patient with SpA of being referred to other specialist may increase up to 25 % depending on the treating centre.

Conclusion

Frequenting rheumatology clinics and referrals to other specialists significantly varies between centres, after adjustment by patient characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous reports have noted variations in the clinical management of a large number of medical conditions [1, 2]. This variability most commonly relates to disease-associated or biologic characteristics; for instance, in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the disease activity and clinical expression may vary depending on the patient’s ethnicity [3–5]. However, biologic factors are not the sole responsible for this differential management; and social or demographic characteristics may have an influence as well. These variations related to non-biological factors may have an effect on the utilisation of healthcare resources. Geographical factors have been shown to alter the rate of hospitalisations [6] and the number of ambulatory care visits [7]. RA patients’ income was also shown to modify the chance of undergoing total joint replacement procedures in a country with public health coverage [8]. This disease-unrelated variability has been noted in non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders as well [9].

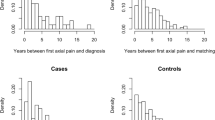

However, to date, scant attention has been paid on whether socio-economic factors may influence management and utilisation of healthcare resources in patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA). A sole study, by Healy et al. [10], found that patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) living in socially deprived areas presented with higher disease activity, poorer functional status and greater use of biological therapy. We recently noted that certain characteristics of the centre where the patient is being managed—i.e. the availability of musculoskeletal ultrasound at the rheumatology unit-, led to significant variations in hospital admission rates of patients with SpA [11]. The potential impact of centre characteristics in other healthcare resource utilisation has not been evaluated so far. Our hypothesis was that ambulatory care varied between centres, with less frequenting in those without a special interest in the pathology, regardless patients’ characteristics (Fig. 1).

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to explore the variability in the frequenting of patients with SpA to the rheumatology clinics, as well as to explore which centre features may lead to this variability, after adjustment by disease and patient characteristics. A secondary outcome was to explore the variability in referrals from rheumatology to other medical specialties.

Methods

Study design, centres, and patients

The emAR II (“Estudio de la variabilidad en el manejo de la artritis reumatoide en España”) was a nation-wide cross-sectional audit study aimed at assessing the variability in the management of patients with RA and SpA, in terms of follow-up measures, utilisation of healthcare resources, procedures, and treatments. The study design has been described elsewhere [12, 13]. The study was performed in Spain in 2009–2010. Health records of patients followed in rheumatology units were selected for review, by 2-stage stratified sampling. First, a list of the public centres was obtained from the National Catalogue of Hospitals [14]. In order to avoid very homogeneous but insufficiently representative samples, probability weights were assigned to each hospital based on size; 100 hospitals were selected. The centres were contacted through a standard letter, offering to participate in the study. In case of no answer or refusal without providing a reason, phone contact was attempted, in order to gather minimal information and to re-offer participation. The selected centres that agreed to participate forwarded an anonymised list of SpA patients with the last visit date; at the last step, 25 patients’ health records were selected by simple random sampling per centre.

Inclusion criteria for this analysis were (a) patients over 16 years old; (b) a diagnosis of SpA registered in the health records; and (c) having attended the clinic at least once in the previous 2 years. Patients were excluded if health records were missing. The clinical diagnosis registered in the patient health records was taken as the type of SpA for the purpose of this study, but the individual items of the main SpA classification criteria were also registered—except for the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) classification criteria [15], as the study was designed and performed before their publication. In the case of psoriatic arthritis, fulfilment of specific classification criteria was not registered.

Variables and data collection

All data refer to the previous 2 years (2007–2008) or to the diagnosis. A detailed list of the variables collected in the emAR II study can be found in an online Appendix (section I). Data regarding attendance to the following clinics were analysed: rheumatology, other medical specialties, specialised nurse, and other health professionals—physiotherapy, psychology, social work. In case of attendance to other medical specialties, it was registered whether the patient was referred by the rheumatologist or not.

Clinical variables included—full list supplied as supplementary material, section I—date of diagnosis, type of SpA, classification criteria fulfilment, mean disease activity and function scores, extra-articular involvement, median levels of inflammatory markers, and comorbidities. Non-clinical variables included (a) those related to the patient, namely age, gender, marital status, educational level, distance from home to the hospital, work activity, sick leave periods; (b) those related to the centre, such as population covered, number of beds, availability of electronic health records, electronic admissions, and electronic diagnostic procedures; (c) to the rheumatology unit, such as number of hospitalisations per year, rheumatology trainees, number of first visits per year, time from referral to first specialised visit, availability of telephone consultations, musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasound in the unit, SpA specialist clinics (as considered by local investigators), participation in SpA clinical trials; and (d) age, gender, experience and position of the primary contact physician—defined as that who signed at least half of the patient visits in rheumatology. Data from centres which were selected but refused to participate were also collected, in order to analyse generalisability of data from participating centres.

Data were collected in electronic case report forms (CRF) by trained investigators from each centre. To ensure anonymisation, patients and centres were given a seven-digit code known only by the local investigator.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the dependent and independent variables was done using central tendency measures (average or median) and dispersion measures (SD 25 and 75 percentiles) for continuous variables, and frequencies for qualitative variables. Frequenting rates were calculated for the two-year study period.

The association of each independent variable with the dependent variable (number of visits to rheumatology clinics) was assessed calculating raw β coefficients with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) and R 2 through simple linear regression. For the purpose of referrals to other medical specialists, the dependent variable was dichotomized (visits requested or not by the rheumatologist) and analysed calculating raw odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) through logistic regression.

To assess variability, three models of multilevel regression of random intercept with non-random slope were built; linear regression was used for number of visits and logistic regression for referrals. The advantage of multilevel analyses, in comparison with multivariate regression, is that it permits classifying variables in different hierarchies (levels), being able to differentiate which percentage of variability relates to variables from each level [16]. Two levels were considered for the analysis: level 1 or patient level, and level 2 or centre level. The multilevel regression was performed in three steps: Model 1 (empty model) included the dependent variable (visits or referrals) and the centre level. Model 2 included Model 1 plus adjustment for the patient’s variables with random effects. In Model 3, also random effects, the adjustment considered both the patients’ and centres’ variables (levels 1 + 2), and it was considered the multivariate global model. Models 2 and 3 included variables statistically significant in the bivariate analysis, and those deemed clinically relevant or potential confounders as explanatory factors. Variables were excluded from the models if showing significant correlation to each other, in order to avoid underpowered models. Analyses were reiterated manually including or excluding factor variables, until achieving the most significant model.

For each model, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), the proportion of variance explained (PVE), and the median odds ratio (MOR), or R 2 depending on the study variable, were calculated. Variability due to hospital factors was considered existing if ICC ≥10 % and p value <0.05 [17].

All analyses were performed with STATA 11.0 software (StataCorp. College Station, USA). Statistical significance was considered as p < 0.05.

Results

Data were available from 1168 patients from 45 centres (47 centres had accepted to participate, but two were excluded as one centre did not complete any CRF during the enrolment period and the other centre only included RA patients—see list of participant centres as supplementary material, section III, table S1). Non-participating centres were similar to participating ones [18].

Patients’ and centres’ characteristics

Data are shown in Table 1. Patients were 50 years old on average, were predominantly men (68 %), and had suffered a longstanding SpA (median duration 105.1 months). Socio-demographic data were missing in more than 20 % of the health records reviewed. A primary contact physician was identified in 94 % of SpA patients; this was predominantly a woman (64.1 %) with a consultant post (74.7 %). Regarding the enrolled centres (see supplementary material, section III, table S1), less than half comprised urban population, half commonly participated in SpA trials, and 31.1 % had SpA specialist clinics.

Frequenting and referrals to other medical specialists

The total number of visits to the rheumatology clinic was 5908 in the 2 years study period. The median number of visits was 4 per patient (interquartile range—IQR 3–6), with an attendance rate of 254 per 100 patient-years.

A total of 4307 visits to other medical specialists were registered (data from 1078 patients), median attendance of 2 per patient (IQR 0–5), with a rate of 200 per 100 patient-years. A 68.7 % of patients attended to other specialist clinic at least once in the study period. Per specialty, clinics attended in the study period were mainly ophthalmology (13.2 %), orthopaedics (9.4 %), gastroenterology (9.3 %), and dermatology (8.4 %) (full list of attended specialties is in the supplementary material). A total of 844 (19.6 %, data from 665 patients) visits were identified as referrals from rheumatology. These referrals predominated in larger centres with more population coverage, more urban residents and higher number of admissions (see supplementary material, section IV, table S2).

Nineteen (42.2 %) centres had specialised nurse clinics. The total number of visits to these clinics was 775 (data from 990 patients), with an attendance rate of 39 per 100 patient-years. The attendance to other health professionals was as follows: 7.4 % to physiotherapists, 0.9 % to psychologists, and 0.9 % to social workers; 3.7 % of patients attended SpA education programmes. More than half the patients did not attend any health professional besides the rheumatologist; 2.3 % of patients were evaluated by rehabilitation because of their SpA.

Variables associated with frequenting

The results of the association analysis of visits to rheumatology clinics are shown in the supplementary material, section V, table S3. Regarding patient characteristics, current age and age at start of SpA symptoms were significantly but negatively associated with visits, while gender or other demographic variables were not. Infections were the only comorbidity with a significant association with frequenting. Regarding SpA variables, the type of SpA or criteria set fulfilment was not associated with visits, except for ESSG criteria, that associated with more visits. A familiar background of SpA was significantly associated with attendance, as was noted for increased serum inflammatory markers levels and for the use of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi). BASDAI and BASFI scores were not included in the analysis, as over 70 % of values were missing.

Regarding variables related to the primary contact physician, female gender showed a significant association with increased visits, while age and experience were negatively associated. The number of admission beds (both in the centre and assigned to rheumatology), the number of admissions per year, the number of faculties on rheumatology staff, and the number of rheumatology trainees were hospital variables significantly associated with attendance to clinics. Other variables with significant, positive association were the existence of nurse clinics, SpA specialist clinics, early SpA clinics, and taking part in SpA trials.

Variables associated with referrals

The results of the association analysis of referrals to other medical specialists are shown in the supplementary material, section V, table S4. No patient demographic characteristic was significantly associated with referrals, neither was any comorbidity. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-related arthritis showed a negative association with referrals in comparison with AS. ESSG criteria fulfilment also showed a negative association. Treatment with either DMARDs or TNFi was significantly associated with being referred to other specialists. As aforementioned, BASDAI and BASFI scores were not analysed due to significant missing data.

No responsible physician feature showed a significant association with referrals. Regarding centre characteristics, a positive, significant association with referrals was found with the coverage of urban population, number of rheumatology staff, number of rheumatology admission beds, number of trainees, the existence of nurse clinics and SpA specialist clinics, and taking part in SpA trials. Conversely, the time to first visit in rheumatology showed a negative association with referrals to other specialties.

Variability in frequenting rheumatology clinics and referrals

Due to missing data, 994 patients from 45 centres could be included for the multilevel analysis of frequenting, and 430 patients from 34 centres for the analysis of referrals. The results of the multilevel analysis are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

The variability between centres in relation to rheumatology visits was 15.7 % (p < 0.001; Table 2). In Model 2, the included clinical and patient-related variables (Level 1) were age, gender, disease duration, use of DMARDs and use of TNFi, but only DMARDs (β 1.454; 95 % CI 1.113, 1.796) and TNFi (β 4.231; 95 % CI 3.746, 4.715) were significantly associated with frequenting. The centre-related variables included in Model 3 were the number of faculties on staff (β 0.309; 95 % CI 0.155, 0.463) and the number of trainees (β −1.441; 95 % CI −2.526, −0.356), with a significant, positive and negative association with frequenting rates, respectively. The PVE from Model 3 was 29.9 % (R 2 0.475, p < 0.001).

Regarding referrals, centre-related characteristics accounted for a variability of 12.3 % (p < 0.001; Table 3). Variables with higher percentage of variance explained in Model 2 were age, gender, disease duration, DMARDs use, TNFi use, and type of SpA (using AS as a reference). A significant association with referrals was noted both for TNFi (OR 1.984; 95 % CI 1.288, 3.056) and for DMARDs (OR 1.603; 95 % CI 1.175, 2.186). Compared to AS, PsA had less referrals (OR 0.532; 95 % CI 0.312, 0.907), as well as IBD-related SpA (OR 0.139; 95 % CI 0.037, 0.515), while other forms of SpA did not differ. To build Model 3, the level 2 variables percentage of urban population (OR 1.237; 95 % CI 1.309, 1.399), number of procedures (OR 1.011; 95 % CI 1.001, 1.020), and the existence of SpA specialist clinic (OR 1.762; 95 % CI 1.101, 2.821) were included and showed significant association with referrals. The PVE of Model 3 was 92.1 % (p = 0.037). MOR was 1.25, meaning that the chance of a patient with SpA being referred by the rheumatologist to other specialists may be 25 % higher depending on the treating hospital.

Discussion

To date, this is the first study that has analysed and demonstrated variations in frequenting and referrals of patients with SpA in relation to centre characteristics. A variability of 15.7 % in visits to rheumatology clinics of patients with SpA was noted. The number of faculties on the staff was significantly associated with more visits, while the number of trainees was associated with fewer visits. Regarding referrals to other clinics by rheumatology, the centre-related variability was 12.3 %; urban population, number of procedures, and the existence of SpA specialist clinics were the centre-related variables significantly associated with this variability.

Many AS patients are part of the actively working population and present frequent sick leave periods and absenteeism [19, 20]. This work absenteeism is mainly related to disease activity, but attending rheumatology or other clinics in relation to their management could be an additional reason that should not be neglected. In the present study, we have shown a significant variability in the number of visits in relation to centre-related factors. Identifying non-biological factors that lead to variations in the utilisation of healthcare resources appears essential in order to design strategies to reduce these differences. Telephone line consultation has been proposed as a tool to reduce in person attendances to clinics, especially out of hours [21]; however, the present study did not find an association between having a telephone line and the number of rheumatology visits. Other forms of telemedicine, such as e-mail communication with patients or electronic consultations between the general practitioner and the rheumatologist, were not evaluated, though they might also have an impact in ambulatory frequenting [22].

Interestingly, the existence of SpA specialist clinics increases referrals by the rheumatologists to other medical specialties. Out of the 45 centres included, only a third had SpA dedicated clinics. The existence of these clinics in a certain unit may indicate a special interest in this group of diseases, especially for research purposes. Physicians running dedicated SpA clinics have an increased awareness about the complete spectrum of the SpA disease, which includes the eye, skin, and gastrointestinal involvement [23], indeed the most attended specialties in the present study. Besides these referrals, the implication of rheumatologists in SpA specialist clinics might involve other areas of patients’ health, perhaps more often requesting other specialists’ opinion rather than leaving the patient in the care of general practitioners. Both could explain the noted association with the referrals. However, this finding should not derive in considering that dedicated clinics lead to increased expenses; neither cost nor cost-benefit outcomes were analysed in this study.

Use of DMARDs and TNFi was both associated with visits to the rheumatologists and referrals to other specialties. Several factors may explain this. Patients with SpA requiring DMARDs and, especially, TNFi usually suffer from a more severe form of disease, and this increases the use of outpatient care resources, in comparison with milder forms or after achieving remission [24]. BASDAI and BASFI scores may be taken as markers of SpA severity and would support this point. Ara et al. [25] found that both scores correlated with the total annual per patient cost in AS, especially in terms of outpatient care, physiotherapy, and medication. However, missing data limited this analysis in the present study. Also, these treatments require regular monitoring for potential toxicity, and this, if performed by the rheumatologist, may determine an increased frequenting to clinics [26].

The attendance of SpA patients to health professional clinics in our study can be considered low: only 42 % of recruited centres had a specialised nurse clinic, in only 7 % of cases a visit to physiotherapist was registered in the records, and attendance to other professionals was anecdotal. These findings contrast with the reported advantages of the intervention of health professionals in the management of rheumatic diseases [27, 28], particularly in the case of AS, where physical therapy still plays a pivotal role [29, 30]. This low utilisation of health professional resources may be country specific, as in Spain the access in the public health system to these professionals (besides nursing) is limited due low availability; however, the utilisation may be higher than shown, as many patients tend to attend private clinics, especially for physiotherapy, with no annotation in patients’ records.

In the present study, comorbidities showed a low impact in ambulatory care of patients with SpA, except for chronic infections, which associated with more visits. Regarding referrals, no significant association was found with comorbidities. To our knowledge, this issue had not been addressed before in SpA patients, but it clearly contrasts to previous reports on general population [31, 32]. The most prevalent conditions were selected; anxiety and depression were not covered, and these might have a role on frequenting and referring of patients with SpA, as happened in other chronic disorders [33]. It is also possible that patients with comorbidities are already been followed by other specialists so no referral from rheumatology is needed.

Type of SpA showed a different chance of being referred to other specialist, being lower for PsA and IBD-related arthritis compared to AS after multivariate analysis. Scant literature has assessed patterns of referrals of patients with SpA between medical specialists other than from primary care [34, 35]. It can be argued that those patients with PsA or IBD arthritis are already being treated by dermatologists or gastroenterologists, so no referral from rheumatologist is needed, but more search on this topic is needed. On the other hand, more complex diseases are expected to need more referrals, and this is suggested by the positive association found with the existence of SpA specialist clinics; also, other aspects of the disease (i.e. cardiovascular, mental) may be systematically assessed there, what may also increase the need for consulting other specialists.

One strength of the present study is to acquire data from a high number of patients’ records randomly selected from a representative sample of rheumatology units around the country. Centres were recruited using an equiprobabilistic method to avoid recruiting mostly tertiary centres with specialised SpA clinics, which might have led to a less representative sample and compromise generalisability.

The results of the study might be limited due to missing data, a common issue of studies auditing patients’ health records. This specially affects sociodemographic variable and BASDAI/BASFI scores. However, the final sample can be considered large, even for the multilevel analysis. Also, statistically significant results were obtained. The relevance of missing data seems therefore limited for the present study, especially for referrals, where the identified centre-related variables explained most of their variability (PVE 92.1 %). However, referrals assessment was a secondary endpoint of the present work and, as only 430 patients were included in multilevel analysis, the study might be unpowered to find differences here. For clinic frequenting, other hospital factors not included in the study could likely explain the remaining variability. In any case, the significant missing data should warrant further studies—especially prospective cohorts—to confirm the finding of the present study. Other concern might relate to the external validity of the results, as this audit was conducted in Spain. The Spanish healthcare system is public, taxpayer funded, and with universal coverage, and it does not differ notably between regions. This is, therefore, comparable to the healthcare systems of the majority of the European Union countries, so findings of the present study could apply at least to them; concerns may arise about the generalisability for insurance-based healthcare systems. In order to properly assess non-clinical features and to adjust also for clinical, we had to include a large number of study variables. So, concerns might arise about significant associations found just by overadjustment [36], but most of variables were not included in the multivariate analysis after shown no association in the bivariate one, and multilevel methodology allowed us to analyse two groups of variables at two stages, minimising the influence of multiplicity on the results.

In summary, the present study has demonstrated the existence of variations in rheumatology clinic frequenting, and in referrals to other specialties in SpA, related to centre factors. This variability may have a significant economic impact in health systems, though it should be confirmed by cost analysis studies. Identifying non-biological variables that lead to differences in healthcare resources utilisation appears essential to design strategies to minimise their effect.

References

Wennberg JE (1984) Dealing with medical practice variations: a proposal for action. Health Aff (Millwood) 3:6–32

Eddy DM (1984) Variations in physician practice: the role of uncertainty. Health Aff (Millwood) 3:74–89

Del Rincón I, Battafarano DF, Arroyo RA, Murphy FT, Fischbach M, Escalante A (2003) Ethnic variation in the clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: role of HLA-DRB1 alleles. Arthritis Rheum 49:200–208

Greenberg JD, Spruill TM, Shan Y, Reed G, Kremer JM, Potter J, Yazici Y, Ogedegbe G, Harrold LR (2013) Racial and ethnic disparities in disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 126:1089–1098

Yazici Y, Kautiainen H, Sokka T (2007) Differences in clinical status measures in different ethnic/racial groups with early rheumatoid arthritis: implications for interpretation of clinical trial data. J Rheumatol 34:311–315

Clarke AE, Esdaile JM, Hawkins D (1993) Inpatient rheumatic disease units: are they worth it? Arthritis Rheum 36:1337–1340

Katz S, Vignos PJ Jr, Moskowitz RW, Thompson HM, Svec KH (1968) Comprehensive outpatient care in rheumatoid arthritis. A controlled study. JAMA 206:1249–1254

Loza E, Abásolo L, Clemente D et al (2007) Variability in the use of orthopedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Spain. J Rheumatol 34:1485–1490

Vitale MG, Krant JJ, Gelijns AC et al (1999) Geographic variations in the rates of operative procedures involving the shoulder, including total shoulder replacement, humeral head replacement, and rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81:763–772

Healey EL, Haywood KL, Jordan KP, Garratt AM, Packham JC (2010) Disease severity in ankylosing spondylitis: variation by region and local area deprivation. J Rheumatol 37:633–638

Andrés M, Sivera F, Vela P, Pérez-Vicente S, emAR-II study group (2014) Centre-related features determine variability of hospital admissions of patients with spondyloarthritides in Spain. Ann Rheum Dis. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-eular.1693

Casals-Sánchez JL, De Yébenes G, Prous MJ, Descalzo Gallego MÁ, Barrio Olmos JM, Carmona Ortells L, Hernández García C, grupo de Estudio emAR II (2012) Characteristics of patients with spondyloarthritis followed in rheumatology units in Spain. emAR II study. Reumatol Clin 8:107–113

Jovani V, Loza E, de Yébenes MJG et al (2012) Variability in resource consumption in patients with spondyloarthritis in Spain. Preliminary descriptive data from the emAR II study. Reumatol Clin 8:114–119

National Catalogue of Hospitals. Ministerio de Sanidad, Asuntos Sociales e Igualdad. http://www.msssi.gob.es/ciudadanos/prestaciones/centrosServiciosSNS/hospitales. Accessed 4 June 2016

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R et al (2009) The development of Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society Classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 68:777–783

Diez-Roux AV (2000) Multilevel analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health 21:171–192

Merlo J, Chaix B, Yang M, Lynch J, Råstam L (2005) A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: linking the statistical concept of clustering to the idea of contextual phenomenon. J Epidemiol Community Health 59:443–449

The emAR-II Study report [spanish]. http://www.ser.es/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/EMAR_Informe.pdf. Accessed 4 June 2016

Boonen A, Chorus A, Miedema H, van der Heijde D, van der Tempel H, van der Linden SJ (2001) Employment, work disability, and work days lost in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross sectional study of Dutch patients. Ann Rheum Dis 60:353–358

Mau W, Listing J, Huscher D, Zeidler H, Zink A (2005) Employment across chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases and comparison with the general population. J Rheumatol 32:721–728

Bunn F, Byrne G, Kendall S (2004) Telephone consultation and triage: effects on health care use and patient satisfaction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD004180

Roberts LJ, Lamont EG, Lim I, Sabesan S, Barrett C (2012) Telerheumatology: an idea whose time has come. Intern Med J 42:1072–1078

Brophy S, Pavy S, Lewis P et al (2001) Inflammatory eye, skin, and bowel disease in spondyloarthritis: genetic, phenotypic, and environmental factors. J Rheumatol 28:2667–2673

Barnabe C, Thanh NX, Ohinmaa A et al (2013) Healthcare service utilization costs are reduced when rheumatoid arthritis patients achieve sustained remission. Ann Rheum Dis 72:1664–1668

Ara RM, Packham JC, Haywood KL (2008) The direct healthcare costs associated with ankylosing spondylitis patients attending a UK secondary care rheumatology unit. Rheumatol (Oxf) 47:68–71

Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X et al (2011) 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 70:896–904

Koksvik HS, Hagen KB, Rødevand E, Mowinckel P, Kvien TK, Zangi HA (2013) Patient satisfaction with nursing consultations in a rheumatology outpatient clinic: a 21-month controlled trial in patients with inflammatory arthritides. Ann Rheum Dis 72:836–843

Temmink D, Hutten JB, Francke AL, Abu-Saad HH, van der Zee J (2000) Quality and continuity of care in Dutch nurse clinics for people with rheumatic diseases. Int J Qual Health Care 12:89–95

Dagfinrud H, Kvien TK, Hagen KB (2008) Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD002822

van den Berg R, Baraliakos X, Braun J, van der Heijde D (2012) First update of the current evidence for the management of ankylosing spondylitis with non-pharmacological treatment and non-biologic drugs: a systematic literature review for the ASAS/EULAR management recommendations in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol (Oxf) 51:1388–1396

Carmona M, García-Olmos LM, García-Sagredo P et al (2013) Heart failure in primary care: co-morbidity and utilization of health care resources. Fam Pract 30:520–524

Hogan P, Dall T, Nikolov P, American Diabetes Association (2003) Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2002. Diabetes Care 26:917–932

Egede LE (2007) Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 29:409–416

Sieper J, Rudwaleit M (2005) Early referral recommendations for ankylosing spondylitis (including pre-radiographic and radiographic forms) in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis 64:659–663

López-González R, Hernández-Sanz A, Almodóvar-González R, Gobbo M, Grupo Esperanza (2013) Are spondyloarthropathies adequately referred from primary care to specialized care? Reumatol Clin 9:90–93

Day NE, Byar DP, Green S (1980) Overadjustment in case–control studies. Am J Epidemiol 112:696–706

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge and thank the following colleagues for their significant contribution in the development of the study protocol, electronic database and statistical analysis: César Hernández, María Jesús García de Yébenes, Miguel Ángel Descalzo, Juan Manuel Barrio, Estíbaliz Loza, María Auxiliadora Martín, and Fernando Sánchez. The full list of authors involved in the emAR II study group can be found in the online Appendix (section II). The emAR II study received funding from Abbvie laboratories; the company had no involvement in the study design, data analysis and interpretation or results communication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in the making of this manuscript.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent from patients was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andrés, M., Sivera, F., Pérez-Vicente, S. et al. Centre characteristics determine ambulatory care and referrals in patients with spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol Int 36, 1515–1523 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3544-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3544-x