Abstract

Background

This study evaluates how residents’ evaluations and self-evaluations of surgeon’s teaching performance evolve after two cycles of evaluation, reporting, and feedback. Furthermore, the influence of over- and underestimating own performance on subsequent teaching performance was investigated.

Methods

In a multicenter cohort study, 351 surgeons evaluated themselves and were also evaluated by residents during annual evaluation periods for three subsequent years. At the end of each evaluation period, surgeons received a personal report summarizing the residents’ feedback. Changes in each surgeon’s teaching performance evaluated on a five-point scale were studied using growth models. The effect of surgeons over- or underestimating their own performance on the improvement of teaching performance was studied using adjusted multivariable regressions.

Results

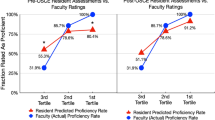

Compared with the first (median score: 3.83, 20th to 80th percentile score: 3.46–4.16) and second (median: 3.82, 20th to 80th: 3.46–4.14) evaluation period, residents evaluated surgeon’s teaching performance higher during the third evaluation period (median: 3.91, 20th to 80th: 3.59–4.27), p < 0.001. Surgeons did not alter self-evaluation scores over the three periods. Surgeons who overestimated their teaching performance received lower subsequent performance scores by residents (regression coefficient b: −0.08, 95 % confidence limits (CL): −0.18, 0.02) and self (b: −0.12, 95 % CL: −0.21, −0.02). Surgeons who underestimated their performance subsequently scored themselves higher (b: 0.10, 95 % CL: 0.03, 0.16), but were evaluated equally by residents.

Conclusions

Residents’ evaluation of surgeon’s teaching performance was enhanced after two cycles of evaluation, reporting, and feedback. Overestimating own teaching performance could impede subsequent performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Eva KW, Regehr G (2005) Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med 80(10 Suppl):S46–S54

Eva KW, Regehr G (2008) “I’ll never play professional football” and other fallacies of self-assessment. J Contin Educ Health Prof 28(1):14–19

Sargeant J, Armson H, Chesluk B et al (2010) The processes and dimensions of informed self-assessment: a conceptual model. Acad Med 85(7):1212–1220

Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH et al (2010) Combined student ratings and self-assessment provide useful feedback for clinical teachers. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 15(3):315–328

Boerebach BC, Arah OA, Busch OR et al (2012) Reliable and valid tools for measuring surgeons’ teaching performance: residents’ vs. self evaluation. J Surg Educ 69(4):511–520

van der Leeuw R, Lombarts K, Heineman MJ et al (2011) Systematic evaluation of the teaching qualities of obstetrics and gynecology faculty: reliability and validity of the SETQ tools. PLoS One 6(5):e19142

Beckman TJ, Ghosh AK, Cook DA et al (2004) How reliable are assessments of clinical teaching? A review of the published instruments. J Gen Intern Med 19(9):971–977

Eva KW, Armson H, Holmboe E et al (2012) Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: on the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 17(1):15–26

Mann K, van der Vleuten C, Eva K et al (2011) Tensions in informed self-assessment: how the desire for feedback and reticence to collect and use it can conflict. Acad Med 86(9):1120–1127

van der Leeuw R, Slootweg IA, Heineman MJ et al (2013) Explaining how faculty act upon residents’ feedback to improve their teaching performance. Med Educ 47:1089–1098

van Roermund T, Schreurs ML, Mokkink H et al (2013) Qualitative study about the ways teachers react to feedback from resident evaluations. BMC Med Educ 13(1):98

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215

Kluger AN, DeNisi A (1996) The effects of feedback interventions on performance: a historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol Bull 119(2):254–284

Korman AK (1970) Toward an hypothesis of work behavior. J Appl Psychol 54(1):31–41

Atwater L, Roush P, Fischthal A (1995) The influence of upward feedback on self- and follower ratings of leadership. Pers Psychol 48(1):35–59

Atwater LE, Ostroff C, Yammarino FJ, Fleenor JW (1998) Self-other agreement: does it really matter? Pers Psychol 51(3):577–598

Brett JF, Atwater L (2001) 360° Feedback: accuracy, reactions, and perceptions of usefulness. J Appl Psychol 86(5):930–942

Johnson JW, Ferstl KL (1999) The effects of interrater and self-other agreement on performance improvement following upward feedback. Pers Psychol 52(2):271–303

Ostroff C, Atwater LE, Feinberg BJ (2004) Understanding self-other agreement: a look at rater and ratee characteristics, context, and outcomes. Pers Psychol 57(2):333–375

Smither JW, London M, Vasilopoulos NL, Reilly RR, Millsap RE, Salvemini N (1995) An examination of the effects of an upward feedback program over time. Pers Psychol 48(1):1–34

Arah OA, Hoekstra JBL, Bos AP et al (2011) New tools for systematic evaluation of teaching qualities of medical faculty: results of an ongoing multi-center survey. PLoS One 6(10):e25983

Lombarts KM, Bucx MJ, Arah OA (2009) Development of a system for the evaluation of the teaching qualities of anesthesiology faculty. Anesthesiology 111(4):709–716

van der Leeuw RM, Overeem K, Arah OA et al (2013) Frequency and determinants of residents’ narrative feedback on the teaching performance of faculty: narratives in numbers. Acad Med 88:1324–1331

Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011) MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45(3):1–67

Singer JD (1998) Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. J Educ Behav Stat 23(4):323–355

Twisk JWR (2006) Applied multilevel analysis: a practical guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Robins JM, Hernán MA (2009) Estimation of the causal effects of time-varying exposures. Longitudinal data analysis. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 553–599

Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B (2000) Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 11(5):550–560

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S et al (2012) Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD000259

Overeem K, Wollersheim H, Driessen E et al (2009) Doctors’ perceptions of why 360° feedback does (not) work: a qualitative study. Med Educ 43(9):874–882

Sargeant J, Mann K, Sinclair D et al (2008) Understanding the influence of emotions and reflection upon multi-source feedback acceptance and use. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 13(3):275–288

Sargeant JM, Mann KV, van der Vleuten CP et al (2009) Reflection: a link between receiving and using assessment feedback. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 14(3):399–410

Brutus S, Fleenor JW, McCauley CD (1999) Demographic and personality predictors of congruence in multisource ratings. J Manag Dev 18:417–435

Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M et al (2006) Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 296(9):1094–1102

Sargeant J, McNaughton E, Mercer S et al (2011) Providing feedback: exploring a model (emotion, content, outcomes) for facilitating multisource feedback. Med Teach 33(9):744–749

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all surgeons and residents for their participation in this study. We also want to thank Anne Huitema for her assistance with the data preparation and analysis and http://medox.nl for the maintenance and optimization of the web-based SETQ application.

Funding

This study is part of the research project Quality of Clinical Teachers and Residency Training, which is co-financed by the Dutch Ministry of Health; the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam; and the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences of the University of Maastricht. Funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Disclosures

None.

Ethical Approval

Waiver of ethical approval was provided by the institutional review board of the Academic Medical Center of the University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 4, 5, 6 and Fig. 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boerebach, B.C.M., Arah, O.A., Heineman, M.J. et al. The Impact of Resident- and Self-Evaluations on Surgeon’s Subsequent Teaching Performance. World J Surg 38, 2761–2769 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2655-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2655-3