Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to compare the prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs) and potential prescribing omissions (PPOs) using several screening tools in an Irish community-dwelling older cohort, to assess if the prevalence changes over time and to determine factors associated with any change.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study of participants aged ≥65 years in The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) with linked pharmacy claims data (n = 2051). PIM and PPO prevalence was measured in the year preceding participants’ TILDA baseline interviews and in the year preceding their follow-up interviews using the Screening Tool for Older Persons’ Prescriptions (STOPP), Beers criteria (2012), Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) indicators and the Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment (START). Generalised estimating equations were used to determine factors associated with change in prevalence over time.

Results

Depending on the screening tool used, between 19.8 % (ACOVE indicators) and 52.7 % (STOPP) of participants received a PIM at baseline, and PPO prevalence ranged from 38.2 % (START) to 44.8 % (ACOVE indicators), while 36.7 % of participants had both a PIM and PPO. Common criteria were aspirin for primary prevention (19.6 %) and omission of calcium/vitamin D in osteoporosis (14.7 %). Prevalence of PIMs and PPOs increased at follow-up (PIMs range 22–56.1 %, PPOs range 40.5–49.3 %), and this was associated with patient age, female sex, and numbers of medicines and chronic conditions.

Conclusions

Sub-optimal prescribing is common in older patients. Ongoing prescribing review to optimise care is important, particularly as patients get older, receive more medicines or develop more illnesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medicines are the most common healthcare intervention worldwide, and despite providing many benefits, they also carry potential risks which can lead to patient harm [1]. Physiological changes in ageing which alter drug pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics can predispose older people to adverse drug events [2]. Additionally, older people are more likely to be taking multiple medicines and have multiple medical conditions, increasing the likelihood of drug-drug or drug-disease interactions [2–4].

Due to concerns regarding appropriate medication use in this age group, a number of screening tools/criteria have been devised to define what constitutes potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP) in the elderly. PIP can be classified as either (i) potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs), the use of a medicine where no clear clinical indication exists or the use of an indicated medicine in circumstances where the risks outweigh the benefits, or (ii) potential prescribing omissions (PPOs), not prescribing a beneficial medicine for which there is a clear clinical indication [5].

Although PIP can be determined implicitly on the basis of clinician’s judgement, the majority of research has determined it explicitly using published criteria/screening tools, a large number of which have been developed [5]. The earliest such tool was Beers criteria, first published in 1991 as a list of drugs to be avoided in older nursing home residents [6]. It contained many medicines not commonly prescribed outside of the USA, and updates to the Beers criteria include drugs which are more widely used internationally and also drugs to avoid with certain conditions [7]. Although earlier iterations of the Beers criteria have been used extensively in the literature, the 2012 criteria have yet to be widely applied [8]. The Screening Tool for Older Person’s Prescriptions (STOPP) and Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment (START) were developed as screening tools for PIMs and PPOs, respectively, suitable for use in European countries and have been applied and validated in the literature [9–12]. Outside of specific PIP screening tools, the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) indicators were developed by the Research and Development (RAND) Corporation to assess the overall quality of care of older people [13]. Several ACOVE indicators relate to PIMs and PPOs, and these have been assessed for use as a PIP screening tool and have good inter-rater reliability [14, 15].

Much published literature on this topic has only focussed on PIMs with few studies utilising PPO screening tools. Of those studies that considered both PIMs and PPOs, none have reported how these two forms of PIP overlap [16–21]. Additionally, little is known about how the prevalence of PIMs and PPOs changes over time in older populations and determinants of change. This study aims to (i) compare the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing (both PIMs and PPOs) in a cohort of community-dwelling people aged 65 years and older in Ireland according to a number of screening tools and (ii) assess if the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in this cohort changes over time and to determine the factors associated with any change.

Methods

Study population

The population for this prospective cohort study comprised a subset of participants in The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) for whom medication dispensing history was available. TILDA is a nationally representative cohort study of more than 8000 community-dwelling people aged 50 years or over charting their health, social, and economic circumstances (see Supplementary file 1 for details of collected information). TILDA participants were deemed eligible for this study if they were aged 65 years or older at baseline and supplied a valid General Medical Services (GMS) identifier to allow linkage of their medication dispensing history from the Health Service Executive Primary Care Reimbursement Service (HSE-PCRS) pharmacy claims database. The HSE-PCRS GMS scheme provides free health services to eligible persons in Ireland, including a wide range of prescribed medicines, although a monthly co-payment per prescription item has applied since October 2010. Eligibility for the GMS scheme is based on means testing, although all people aged over 70 were eligible until December 2008 when a higher income threshold was introduced for this age group compared to the general population.

Data collection

TILDA participant recruitment and wave 1 baseline data collection were carried out between 2009 and 2011 when participants were interviewed face to face, completed a questionnaire and underwent a health assessment. TILDA follow-up waves are scheduled every 2 years, the first of which was carried out from February 2011 to March 2012. Medication data were extracted from the HSE-PCRS pharmacy claims database on the basis of GMS identifier for each participant in the present study for the 15 months preceding the date of their TILDA baseline and follow-up interviews. The HSE-PCRS database contains a GMS identifier, sex and date of birth, drug information (World Health Organisation Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code, strength, defined daily dosage (DDD)), quantity dispensed and date of dispensing. Linkage of participants’ TILDA and HSE-PCRS dispensing data was carried out using methods published previously [22]. All data were anonymised after linkage was performed. Ethical approval for TILDA was provided by the Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee at Trinity College Dublin.

Potentially inappropriate prescribing criteria

The prevalence of PIP was measured during two time intervals: in the 12 months preceding each participant’s baseline TILDA interview and in the 12 months preceding their follow-up interview. A longer period of time was analysed for criteria dependent on duration of medication use of greater than 1 month to allow for 12 months of potential exposure. Dispensing data from the HSE-PCRS database and information from TILDA on diagnoses, medications not included in the HSE-PCRS database (self-reported) and other characteristics were used to assess if participants had received a PIM or had a PPO. Participants were classified as having a PIM if they were prescribed the potentially inappropriate medicine at any time during the study periods, while having a PPO was classified as not receiving the indicated medicine at any time during the study periods.

A subset of criteria from STOPP, Beers criteria (2012) and the third iteration of the ACOVE indicators were applied to dispensing data and information from TILDA to measure PIMs. Forty-five of 65 (69 %) STOPP criteria, 42 of 52 (81 %) Beers criteria and 17 of 22 (77 %) ACOVE indicators relating to inappropriate medicines were used. To measure PPOs, a subset of criteria from START and the ACOVE indicators were used. Fifteen of 22 (68 %) START criteria were applicable, while 21 of 65 (34 %) ACOVE indicators relating to prescribing indicated that medicines could be applied. All criteria for which the necessary participant information was available in the HSE-PCRS pharmacy claim that database and TILDA were applied.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates were calculated for each set of PIM and PPO criteria as well as for each individual criterion. Additionally, the prevalence of each criterion (where applicable) as a proportion of the number of participants with the condition/disease or prescribed the drug of interest was determined, for example, of those prescribed a benzodiazepine during the study period, the proportion who were prescribed it for >4 weeks. McNemar’s test for paired groups comparison was used to test whether the prevalence of criteria changed significantly between the two time periods. Generalised estimating equations (GEE) with exchangeable correlations were used to investigate determinants of the change in prevalence of PIMs and PPOs [23]. Unadjusted analysis estimating change in overall PIM and PPO prevalence from baseline to follow-up was followed by multivariable GEE analysis which adjusted for sex, age, numbers of regular medicines and diagnosed chronic conditions (reported at TILDA interview) at baseline and follow-up in the models. Level of educational attainment as an indicator of socio-economic status was assessed for inclusion in the models. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata version 12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics

This study included 2051 TILDA participants (Fig. 1), of which 1107 (53.97 %) were female, and mean participant age (SD) in this sample was 74.8 (6.2) years. Mean number of reported regular medicines (SD) increased from 4.1 (2.9) at baseline to 4.9 (3.2) at follow-up, while mean number of chronic conditions reported (SD) was 2.4 (1.6) and 2.9 (1.7) at TILDA baseline and follow-up interviews, respectively.

Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicine use and potential prescribing omissions

When assessed using STOPP, 1081 participants (52.7 %) were prescribed a PIM during the baseline study period, while prevalence of Beers PIMs and ACOVE PIMs was significantly lower (30.5 and 19.8 % respectively, p < 0.05). The prevalence of PPOs at baseline was 44.8 % when assessed using ACOVE indicators and 38.2 % using START (see Table 1). Overall, 61.4 % of the sample had a PIM defined by any of the screening tools, 53.3 % had any PPO and 753 (36.7 %) participants had both a PIM and PPO. A total of 2963 PIMs and 2315 PPOs were identified during this study period.

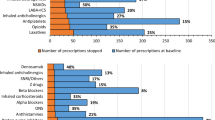

The most common (prevalence >2 %) individual PIM criteria and PPO criteria are reported in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. All applied criteria are presented in Supplementary file 2. The most prevalent baseline PIM criteria were aspirin with no history of coronary, cerebral or peripheral arterial symptoms or occlusive arterial event (STOPP, 19.6 %) and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) at full therapeutic dosage for >8 weeks (STOPP, 17.2 %). The most prevalent baseline PPO criteria were calcium and vitamin D supplement omission in patients with self-reported osteoporosis (ACOVE indicators and START, 14.7 %) and omission of a laxative in an older person with persistent pain treated with opioids (ACOVE indicators, 11.0 %).

Change in prevalence over time

The prevalence of PIMs and PPOs increased significantly (p < 0.05) between the baseline and follow-up study periods for each screening tool (Table 1). At follow-up, 64.8 % of participants received a PIM, and 56.6 % received a PPO defined by any of the screening tools, while the proportion of the sample with both a PIM and PPO increased to 41.1 % (843 participants).

The prevalence of PIMs increased between waves and the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for the presence of any PIM, comparing follow-up to baseline, was 1.08 (95 % CI 1.03, 1.13), using unadjusted GEE analysis. A multivariate GEE model (Table 4) showed that female sex, age and higher number of medicines were significantly associated with change in PIM prevalence and the change in prevalence at follow-up compared to baseline was not significant after adjusting for these covariates. Similarly for PPO prevalence, the association for follow-up compared to baseline in the unadjusted analysis (OR 1.07, 95 % CI 1.02, 1.11) was no longer significant in the multivariable model (Table 4), where age and higher numbers of medicines and chronic conditions were found to be significantly associated with change in PPO prevalence. When included, level of education was not significant in the models and adjusting for it did not alter any of the other odds ratios.

The most common PIM and PPO criteria (prevalence >2 %) during the follow-up period are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. A number of individual criteria showed highly significant (p < 0.0001) increases in prevalence between baseline and follow-up, including prescription of PPIs at full therapeutic dosage for >8 weeks (STOPP, 17.2 to 21.9 %). Only prescription of long-term (>1 month) long-acting benzodiazepines (STOPP/ACOVE, 3.9 to 3.1 %) and omission of antihypertensives in participants with elevated blood pressure (START, 5.5 to 3.5 %) significantly decreased in prevalence.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

This study showed in a cohort of 2051 community-dwelling people aged 65 and over, more than 61 % received a PIM in a 1-year period defined by a subset of STOPP criteria, Beers criteria and ACOVE indicators, while 53 % had a PPO defined by a subset of START criteria and ACOVE indicators. Aspirin for primary prevention, prolonged use of full therapeutic dosage PPIs and strong anticholinergic drugs were the most common PIMs, while common omissions were calcium and vitamin D in osteoporosis, laxatives for patients on opioids and gastro-protection with an NSAID. The increase in PIM and PPO prevalence between baseline and follow-up is associated with patient characteristics (age, female sex, numbers of prescribed medicines and chronic conditions) rather than being a function of time.

Results in the context of current literature

It is not surprising that the prevalence varies depending on the screening tool used as each includes different types of prescribing in what is classified as potentially inappropriate. Also, the Beers criteria and ACOVE indicators were first developed for use in the USA, whereas STOPP and START are more widely applicable. A number of studies have estimated the prevalence of PIP using multiple screening tools. Prevalence estimates have been highly variable as research has been carried out across settings (hospitals, residential care, community), in a number of countries and using data ranging from full clinical records to administrative data meaning that only a subset of PIP criteria have been applied [17].

A systematic review of studies applying the STOPP and/or START criteria found prevalence ranging from 21 to 79 % for PIMs and 22 to 74 % for PPOs [12]. PIM prevalence according to the Beers criteria varied from 3 to 40 % in studies included in a review of the 1991 Beers criteria, and up to 53.4 % using more recent iterations of Beers criteria [24, 25]. The ACOVE indicators have not been applied extensively, with two studies reporting the prevalence of ACOVE PPOs giving estimates of 58 and 58.5 % [14, 26]. A previous study of TILDA participants using STOPP/START reported lower PIM and PPO prevalence at baseline interview than the current study (14.6 and 30 %) [21]; however, fewer criteria were applied and prevalence was measured at one time point rather than over a period of 12 months.

A number of studies have assessed the prevalence of both PIMs and PPOs; however, the present study appears to be the first to report on the proportion of study participants with concurrent PIMs and PPOs [16–21]. An association has been demonstrated between polypharmacy (using ≥ five medications concomitantly) and underprescribing [27], so the high rate of concurrent PIMs and PPOs is not unexpected.

Few epidemiological studies have reported the longitudinal prevalence of PIP, and findings have shown a trend of PIP decreasing over time [28, 29]. A cohort study which, like the present study, controlled for numbers of prescribed medicines and co-morbidities found that sub-optimal prescribing remained unchanged or decreased over a 4-year follow-up period after adjusting for these factors [30].

Clinical and policy implications

Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people is a common issue and warrants attention to improve the quality of care provided to this age group. However, this complex problem may not be accurately captured using administrative data. Participants may not have responded to first-line treatment or have contraindications resulting in a PIM being prescribed or an indicated medicine being omitted. Prescribers may have to weigh up the incremental benefit of one additional indicated medicine against increasing the treatment burden in older patients already taking multiple medications. The structure of the health system in Ireland, in particular the lack of implementation of a co-ordinated chronic disease management policy across primary and secondary care, may also contribute to the rate of PIP, and future implementation of this policy could have a positive impact on prescribing [31].

The strength of evidence of inappropriateness varies across criteria and the risk-benefit ratio may have changed since PIP screening tools were developed. For example, aspirin for primary prevention is included in STOPP, but evidence is conflicting on the net benefit in people with cardiovascular risk factors but without previous cardiovascular events/symptoms [32, 33].

A high proportion of study participants have both prescribing errors of commission (PIMs) and omission (PPOs). This suggests that reviewing both suitability of current medicines and assessing the need for additional indicated therapies is necessary to optimise prescribing for older people.

The long-term prescription of full therapeutic dosage PPIs has been identified previously as a particularly common issue in older people and represents a significant cost burden [34]. Though the cost-effective use of PPIs in Ireland has been promoted through policies such as reference pricing and preferred drug schemes, a focus on prescribing appropriate dosages and durations may provide clinical benefits to patients as well as cost savings [35, 36]. Although long-term benzodiazepine use declined in this study, this may be explained by substitution with Z-drug hypnotics which showed a non-significant increase in prevalence. Omission of antihypertensive therapy also declined at follow-up, which may have been due to participants with high blood pressure at baseline interview being advised to discuss this with their general practitioner.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study’s participants are community-dwelling older people from a nationally representative study on ageing, which improves the generalisability of these findings. Although only participants with eligibility to the means-tested GMS scheme were included, a high proportion (73.5 %) of TILDA participants aged over 65 reported GMS eligibility (see Fig. 1).

The use of administrative pharmacy claims data in this study may provide more accurate information on medication exposure than self-reported medication use, although good agreement has been found between such sources [22]. It also allows medication exposure to be determined over a 12-month time period to provide a more accurate assessment of PIM and PPO prevalence, as opposed to using medication data from one point in time which could underestimate PIMs and overestimate PPOs.

A limitation of pharmacy claims data is that patients may not have actually consumed medications dispensed (i.e. if patients are non-adherent), and a lack of information on medicines purchased over-the-counter may lead to an overestimation of some prescribing omissions (e.g. calcium and vitamin D, laxatives). Additionally, there may have been a clinical reason why some participants had a PIM/PPO; however, as no clinical notes were available, it is not possible to determine clinicians’ rationale for such prescribing decisions.

A number of criteria from each of the PIM and PPO screening tools could not be included in this analysis due to the required information not being available in the administrative and survey data used. However, the combination of these data sources allows for a greater number of criteria to be applied than with either source alone [21]. Some information on diagnoses was based on participants self-report and so may not accurately reflect the presence/absence of the conditions of interest.

Conclusions

Although prevalence of PIMs and PPOs can vary depending on the screening tool used, such prescribing issues are common and may become more prevalent in patients with more medicines or chronic illnesses. This underlines the importance of ongoing prescribing review for older patients, both to assess the appropriateness of current drug therapy as well as to evaluate the need for additional clinically indicated treatments. Further research is planned to examine the association between potentially inappropriate prescribing over time and adverse health outcomes.

References

Avorn J (2005) Powerful medicines: the benefits, risks, and costs of prescription drugs. Random House, New York

Mallet L, Spinewine A, Huang A (2007) The challenge of managing drug interactions in elderly people. Lancet 370:185–191

Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R et al (2011) Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 10:430–439. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003

Fulton MM, Riley Allen E (2005) Polypharmacy in the elderly: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 17:123–132. doi:10.1111/j.1041-2972.2005.0020.x

O’Connor MN, Gallagher P, O’Mahony D (2012) Inappropriate prescribing. Criteria, detection and prevention. Drugs Aging 29:437–452

Beers M, Ouslander J, Rollingher I et al (1991) Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 151:1825–1832

American Geriatrics Society (2012) Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (2012) American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:616–631. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x

Jano E, Aparasu RR (2007) Healthcare outcomes associated with Beers’ criteria: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 41:438–447. doi:10.1345/aph.1H473

Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S et al (2008) STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 46:72–83

Gallagher P, Baeyens J-P, Topinkova E et al (2009) Inter-rater reliability of STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment) criteria amongst physicians in six European countries. Age Ageing 38:603–606. doi:10.1093/ageing/afp097

Ryan C, O’Mahony D, Byrne S (2009) Application of STOPP and START criteria: interrater reliability among pharmacists. Ann Pharmacother 43:1239–1244. doi:10.1345/aph.1M157

Hill-Taylor B, Sketris I, Hayden J et al (2013) Application of the STOPP/START criteria: a systematic review of the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults, and evidence of clinical, humanistic and economic impact. J Clin Pharm Ther 38:360–372. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12059

Wenger N, Roth C, Shekelle P (2007) Introduction to the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders-3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:S247–S252

San-José A, Agustí A, Vidal X et al (2014) An inter-rater reliability study of the prescribing indicated medications quality indicators of the Assessing Care Of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) 3 criteria as a potentially inappropriate prescribing tool. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 58:460–464. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2013.12.006

Pileggi C, Manuti B, Costantino R et al (2014) Quality of care in one Italian nursing home measured by ACOVE process indicators. PLoS ONE 9:e93064. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093064

Ryan C, O’Mahony D, Kennedy J et al (2009) Potentially inappropriate prescribing in an Irish elderly population in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 68:936–947. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03531.x

Conejos Miquel M, Sánchez Cuervo M, Delgado Silveira E et al (2010) Potentially inappropriate drug prescription in older subjects across health care settings. Eur Geriatr Med 1:9–14. doi:10.1016/j.eurger.2009.12.002

Pyszka LL, Seys Ranola TM, Milhans SM (2010) Identification of inappropriate prescribing in geriatrics at a Veterans Affairs hospital using STOPP/START screening tools. Consult Pharm 25:365–373. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2010.365

Gallagher PF, O’Connor MN, O’Mahony D (2011) Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther 89:845–854. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.44

Gallagher P, Lang P, Cherubini A et al (2011) Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of older patients admitted to six European hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67:1175–1188. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1061-0

Galvin R, Moriarty F, Cousins G et al (2014) Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing and prescribing omissions in older Irish adults: findings from The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing study (TILDA). Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70:599–606. doi:10.1007/s00228-014-1651-8

Richardson K, Kenny RA, Peklar J, Bennett K (2013) Agreement between patient interview data on prescription medication use and pharmacy records in those aged older than 50 years varied by therapeutic group and reporting of indicated health conditions. J Clin Epidemiol 66:1308–1316. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.02.016

Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS (1988) Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics 44:1049–1060

Aparasu RR, Mort JR (2000) Inappropriate prescribing for the elderly: Beers criteria-based review. Ann Pharmacother 34:338–346

O’Sullivan DP, O’Mahony D, Parsons C et al (2013) A prevalence study of potentially inappropriate prescribing in Irish long-term care residents. Drugs Aging 30:39–49. doi:10.1007/s40266-012-0039-7

Elseviers MM, Vander Stichele RR, Van Bortel L (2013) Quality of prescribing in Belgian nursing homes: an electronic assessment of the medication chart. Int J Qual Health Care 26:93–99. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzt089

Blanco-Reina E, Ariza-Zafra G, Ocaña-Riola R et al (2015) Optimizing elderly pharmacotherapy: polypharmacy vs. undertreatment. Are these two concepts related? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71:199–207. doi:10.1007/s00228-014-1780-0

Zimmermann T, Kaduszkiewicz H, van den Bussche H et al (2013) Potentially inappropriate medication in elderly primary care patients: a retrospective, longitudinal analysis. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 56:941–949. doi:10.1007/s00103-013-1767-5

Price SD, Holman CDJ, Sanfilippo FM, Emery JD (2014) Are older Western Australians exposed to potentially inappropriate medications according to the Beers Criteria? A 13-year prevalence study. Aust J Ageing 33:E39–E48. doi:10.1111/ajag.12136

Lapi F, Pozzi C, Mazzaglia G, Ungar A (2009) Epidemiology of suboptimal prescribing in older, community dwellers. Drugs Aging 26:1029–1039

Department of Health and Children (2008) Tackling chronic disease: a policy framework for the management of chronic diseases. Dublin

Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H et al (2012) European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J 33:1635–1701. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092

Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM et al (2012) Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 141:e637S–e668S. doi:10.1378/chest. 11-2306

Cahir C, Fahey T, Tilson L et al (2012) Proton pump inhibitors: potential cost reductions by applying prescribing guidelines. BMC Health Serv Res 12:408. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-408

Health Services Executive Medicines Management Programme [Internet]. http://www.hse.ie/yourmedicines. Accessed 1 Jul 2014

Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB (2013) Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 6:443–451. doi:10.1586/17512433.2013.811206

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Health Research Board (HRB) through the HRB PhD Scholars Programme in Health Services Research under Grant no. PHD/2007/16 and the HRB Centre for Primary Care Research under Grant no HRC/2007/1. TILDA was supported by Department of Health and Children, The Atlantic Philanthropies and Irish Life. We wish to thank the Health Services Executive Primary Care Reimbursement Services (HSE-PCRS) for the use of the prescribing database and Kathryn Richardson for her assistance in linking data for the study participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

FM, KB, TF and CC planned and designed this study. Acquisition of data was carried out by RAK (TILDA) and KB (HSE-PCRS). FM and CC performed data linkage and analysis. FM drafted the manuscript, and KB, TF, RAK and CC critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Moriarty, F., Bennett, K., Fahey, T. et al. Longitudinal prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicines and potential prescribing omissions in a cohort of community-dwelling older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71, 473–482 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1815-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1815-1