Abstract

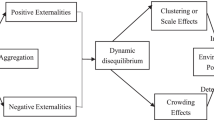

This paper demonstrates that a pollution tax with a fixed cost component capturing an “ambient tax” may lead, by itself, to stratification between clean and dirty firms without heterogeneous preferences or increasing returns. We construct a simple model with two locations and two industries (clean and dirty) where pollution is a by-product of dirty good manufacturing. Under proper assumptions, a completely stratified configuration with all dirty firms clustering in one city emerges as the only equilibrium outcome when there is a fixed cost component of the pollution tax. Whereas the fixed component of the pollution tax and decreasing private returns are needed for agglomeration of dirty firms, the Romer-type positive spillovers are not necessary. Moreover, a stratified Pareto optimum can never be supported by a competitive spatial equilibrium with a linear pollution tax that encompasses Pigouvian taxation as a special case. To support such a stratified Pareto optimum, however, an effective but unconventional policy prescription is to redistribute the pollution tax revenue from the dirty to the clean city residents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Porter (1990) for a comprehensive discussion of industrial clustering from a business strategy viewpoint. Our paper is also related to the locational stratification literature, where stratification is caused by human capital (Benabou 1996a, b; Chen et al. 2009), local public goods (Nechyba 1997; Peng and Wang 2005), and the environment (Chen et al. 2012).

See also Baumol (1972) and Buchanan and Tullock (1975) on direct control versus taxation and Chipman and Tian (2012) on markets for rights to pollute in an aspatial context. While there is an existing literature on the welfare consequences of pollution taxation (see citations in Sect. 7 below), none explores the implication of pollution taxation for production agglomeration, in particular when pollution is local (so location is relevant) and agents are mobile. The point of Carlton and Loury (1980) is different, in that they are concerned with firm entry and exit. We do not consider that in our model.

Karp (2005) goes on to consider the case where firms are large so each has an effect on the aggregate level of pollution.

A natural alternative model, which does not capture this idea, is to use a fixed lump-sum tax for each firm entering the local market. This would clearly not be an ambient tax with a large number of firms.

The reader is referred to Markusen et al. (1995) for modeling fiscal competition in pollution taxes with firms choosing the location of plants.

We wish to emphasize that in this paper, we consider only equilibrium or optimal configurations that are completely stratified in terms of production or that are completely integrated in that production is symmetric across locations. We relegate the discussion of other possible configurations to the concluding section.

The pollution tax schedule is written in this form for analytical convenience.

This functional form also covers the first type of tax mentioned in the introduction because pollution is proportional to output via \(\theta \).

The equilibrium concept is based on the multiclass equilibrium concept constructed by Hartwick et al. (1976).

If there is no tax and both industries have (different) CRS production functions (with no Romer externality) but there is still pollution, then an integrated equilibrium will arise with both wage and utility equalized but with a corner solution in consumption (only the dirty good is consumed).

If one allows the location of dirty city to be in either \(A\) or \(B\), then a standard fork bifurcation diagram is obtained.

In order to separate these two channels (producer rent and magnitude of externality), one must give up social constant returns, assuming instead social decreasing returns: \({\widetilde{f}}\left( n_{y}^{i}(j),N_{y}^{i}\right) =\phi [n_{y}^{i}(j)]^{\beta _{1}}[N_{y}^{i}]^{\beta _{2}}, \phi >0, \beta _{1},\beta _{2}\in \left( 0,1\right) \) and \(\beta _{1}+\beta _{2}<1\). We have tried this but lost analytic tractability.

The public land ownership model features land rent collections that are refunded equally to all inhabitants of a location.

References

Aidt, T.S.: Political internalization of economic externalities and environmental policy. J. Pub. Econ. 69, 1–16 (1998)

Baumol, W.J.: On taxation and the control of externalities. Am. Econ. Rev. 62, 307–322 (1972)

Benabou, R.: Heterogeneity, stratification and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 86, 584–609 (1996a)

Benabou, R.: Equity and efficiency in human capital investment: the local connection. Rev. Econ. Stud. 63, 237–264 (1996b)

Benchekroun, H., van Long, N.: Efficiency inducing taxation for polluting oligopolists. J. Pub. Econ. 70, 325–342 (1998)

Bergstrom, T., Cornes, R.: Independence of allocative efficiency from distribution in the theory of public goods. Econometrica 51, 1753–1765 (1983)

Berliant, M., Peng, S., Wang, P.: Production externalities and urban configuration. J. Econ. Theory 104, 275–303 (2002)

Buchanan, J.M., Tullock, G.: Polluter’s profits and political response: direct control versus taxes. Am. Econ. Rev. 65, 139–147 (1975)

Carlton, D.W., Loury, G.C.: The limitation of Pigouvian taxes as a long-run remedy for externalities. Q. J. Econ. 95, 559–567 (1980)

Chen, B., Peng, S., Wang, P.: Intergenerational human capital evolution, local public good preferences, and stratification. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 33, 745–757 (2009)

Chen, B., Huang, C., Wang, P.: Stratification by environment. J. Pub. Econ. Theory 14, 711–735 (2012)

Chipman, J.S., Tian, G.: Detrimental externalities, pollution rights, and the ‘Coase theorem’. Econ. Theory 49, 309–327 (2012)

Fujita, M.: Urban Economic Theory: Land Use and City Size. Cambridge University Press, New York (1989)

Hartwick, J., Schweizer, U., Varaiya, P.: Comparative statics of a residential economy with several classes. J. Econ. Theory 13, 396–413 (1976)

Helpman, E.: The size of regions. In: Pines, D., Sadka, E., Zilcha, Y. (eds.) Topics in Public Economics. Cambridge University Press, New York (1998)

Karp, L.: Nonpoint source pollution taxes and excessive tax burden. Environ. Res. Econ. 31, 229–251 (2005)

Markusen, J.R., Morey, E.R., Oleviler, N.: Competition in regional environmental policies when plant locations are endogenous. J. Pub. Econ. 56, 55–77 (1995)

Melitz, M.J.: The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71, 1695–1725 (2003)

Nechyba, T.: Existence of equilibrium and stratification in local and hierarchical Tiebout economies with property taxes and voting. Econ. Theory 10, 277–304 (1997)

OECD: Managing the Environment: The Role of Economic Instruments. OECD, Paris (1994)

Peng, S., Wang, P.: Sorting by foot: ‘travel-for’ local public goods and equilibrium stratification. Can. J. Econ. 38, 1224–1252 (2005)

Picard, P.M., Tabuchi, T.: Self-organized agglomerations and transport costs. Econ. Theory 42, 565–589 (2010)

Pigou, A.C.: The Economics of Welfare. Macmillan, London (1920)

Porter, M.E.: The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Free Press, New York (1990)

Romer, P.M.: Increasing returns and long-run growth. J. Polit. Econ 94, 1002–1037 (1986)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful for suggestions from an anonymous referee, Sören Blomquist, John Conley, Katherine Cuff, Hideo Konishi, Ailsa Röell, Steve Slutsky, John Weymark, and Jay Wilson, as well as participants at the Public Economic Theory Conference in Taipei, the Regional Science Association International Meetings in Miami, the Society for Advanced Economic Theory Conference at Faro, and the Taxation Theory Conference at Vanderbilt University. Financial support from Academia Sinica and the National Science Council of Taiwan (grant no. NSC99-2410-H-001-013-MY3) that enabled this international collaboration by the Three Mouseketeers is gratefully acknowledged.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berliant, M., Peng, SK. & Wang, P. Taxing pollution: agglomeration and welfare consequences. Econ Theory 55, 665–704 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-013-0768-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-013-0768-9

Keywords

- Pollution tax

- Agglomeration of polluting producers

- Endogenous stratification

- Pareto optimality of stratified equilibrium