Abstract

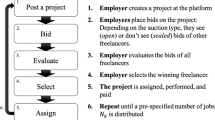

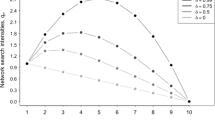

The importance of referral hiring, which is workers finding employment via social contacts, is nowadays an empirically well documented fact. It also has been shown that social networks for finding jobs can create stratification. These analyses are, by and large, based on exogenous network structures. We go beyond the existing work by building an agent-based model of the labor market in which the social network of potential referees is endogenous. Workers invest some of their endowments into building up and fostering their social networks as an insurance device against future job losses. We look into the manner in which social networks and inequality respond to increased uncertainty in the labor market. We find that larger variability in firms’ labor demand reduces workers’ efforts put into social networks, leading to lower inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We may also, perhaps more abstractly, refer to number of links instead of using for illustrative reasons the term friends. In the model which we develop, friends have a particularly narrow meaning which, however, does not imply that we are not aware of much broader interpretations.

More evidence on job search through friends and relatives can be found in the excellent survey by Ioannides and Loury (2004) or the comparative study by Pellizzari (2004). Recent contributions on the role of social networks and labor market performance using microdata are Cingano and Rosolia (2008) and Hellerstein et al. (2008).

See Freeman (2002) for how information and computer technologies changed matching employers and employees in labor markets.

See e.g. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/.

One of our referees brought to our attention the work by McCloskey and Ziliak (1996) arguing that, besides statistical significance, economic importance should also be reflected. While we fully agree, we would refer at this point to our earlier remark that we develop a quite stylized model for the study of economic mechanisms, which makes a quantitative interpretation of the results less straightforward.

Note that the share of referral hirings in our experiment with an exogenously given friend is higher than in Table 2, even though the average number of friends is roughly the same. The reason is that an average number of friends equal to one in a framework in which friends are endogenous implies that some workers do not have friends at all, while others may have two or more. Those who do not have friends will not get referrals and those who have more than one friend might have more friends than they need to get a referral. Thus, on average, the share of referrals will be lower as compared to the experiment in which all workers have one friend.

Results of these robustness checks are all available upon request from the authors.

References

Bertola G, Blau F, Kahn L (2002) Comparative analysis of labour market outcomes: lessons for the U.S. from international long-run evidence. In: Krueger A, Solow R (eds) The roaring nineties: can full employment be sustained? Russell Sage and Century Foundations, pp 159–218

Bewley T (1999) Why wage don’t fall during a recession. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Blanchard O, Wolfers J (2000) Shocks and institutions and the rise of european unemployment: the aggregate evidence. Econ J 110:1–33

Boorman S (1975) A combinatorial optimization model for transmission of job information through contact networks. Bell J Econ 6:216–249

Bramoullè Y, Saint-Paul G (2010) Social networks and labor market transitions. Labour Econ 17:188–195

Brenner T (2006) Agent learning representation: advice on modelling economic learning. In: Judd K, Tesfatsion L (eds) Handbook of Computational Economics, vol 2. North-Holland, pp 895–947

Calvo-Armengol A (2004) Job contact networks. J Econ Theory 115:191–206

Calvo-Armengol A, Ioannides Y (2007) Social networks in labor markets. In: Blume L, Durlauf S (eds) The New Palgrave, A Dictionary of Economics, 2nd edn. MacMillan Press, London, p. forthcoming

Calvo-Armengol A, Jackson M (2004) The effects of social networks on employment and inequality. Am Econ Rev 94:426–454

Calvo-Armengol A, Jackson M (2007) Networks in labor markets: wage and employment dynamics and inequality. J Econ Theory 132:27–46

Camerer C, Ho T (1999) Experienced-weighted attraction learning in normal form games. Econometrica 67:827–874

Cingano F, Rosolia A (2008) People i know: job search and social networks. Center for economic policy research discussion paper no. 6818.

Currarini S, Jackson MO, Pin P (2009) An economic model of friendship: homophily, minorities and segregation. Econometrica 77:1003–1045

Fagiolo G, Dosi G, Gabriele R (2004) Matching, bargaining, and wage setting in an evolutionary model of labor market and output dynamics. Adv Complex Systems 7:157–186

Finneran L, Kelly M (2003) Social networks and inequality. J Urban Econ 53:282–299

Freeman R (2002) The labour market in the new information economy. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 18:288–305

Granovetter M (1974) Getting a job: a study of contacts and careers. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Heckman J (2003) Flexibility, job creation and economic performance. CESifo Forum 4(2):29–32

Hellerstein J, McInerney M, Neumark D (2008) Measuring the importance of labor market networks. NBER working papier series, working paper 14201

Ho T, Wang X, Camerer C (2008) Individual differences in ewa learning with partial payoff information. Econ J 118:37–59

Ioannides Y, Loury L (2004) Job information networks, neighborhood effects, and inequality. J Econ Lit 42:1056–1093

Kirman A (1997) The economy as an evolving network. J Evol Econ 7:339–353

Krauth B (2004) A dynamic model of job networking and social influences on employment. J Econ Dyn Control 28:1185–1204

Ljungqvist L, Sargent T (2008) Two questions about european unemployment. Econometrica 76:1–29

Martin C, Neugart M (2009) Shocks and endogenous institutions: an agent-based model of labor market performance in turbulent times. Comput Econ 33:31–46

McCloskey DN, Ziliak T (1996) The standard error of regressions. J Econ Lit XXXIV:97–114

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook J (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociology 27:415–444

Montgomery J (1991) Social networks and labor-market outcomes: toward an economic analysis. Am Econ Rev 81:1408–1418

Neugart M (2004) Endogenous matching functions: an agent-based computational approach. Adv Complex Systems 7:187–201

Neugart M (2008) Labor market policy evaluation with ace. J Econ Behav Organ 67:418–430

Pellizzari M (2004) Do friends and relatives really help in getting a good job. Centre for economic performance, discussion paper no 623

Pingle M, Tesfatsion L (2003) Evolution of worker-employer networks and behaviors under alternative unemployment benefits: an agent-based computational study. In: Nagurney A (ed) Innovations in economic and financial networks. Edward Elgar Publishers, pp 256–285

Richiardi M (2006) Toward a non-equilibrium unemployment theory. Comput Econ 27:135–160

Tassier T, Menczer F (2001) Emering small world referral networks in evolutionary labor markets. IEEE Trans Evol Comput 5:482–492

Tassier T, Menczer F (2008) Social network structure, segregation and equality in a labor market with referral hiring. J Econ Behav Organ 66:514–528

Wilhite A (2006) Economic activity on fixed networks. In: Judd K, Tesfatsion L (eds) Handbook of computational economics, vol 2. North-Holland, pp 1013–1045

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Herbert Dawid and Philipp Harting and two anonymous referees for their suggestions, as well as all the participants commenting at the Conference of the Eastern Economic Association in Boston 2008, at the Artificial Economics Conference 2008 in Innsbruck, the conference of the European Social Simulation Association in Brescia 2008, the WEHIA conference 2009 in Beijing, the Tagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik 2009, and at the 2009 Cendef conference in Amsterdam, and at research seminars in Pisa and Münster.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gemkow, S., Neugart, M. Referral hiring, endogenous social networks, and inequality: an agent-based analysis. J Evol Econ 21, 703–719 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-011-0219-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-011-0219-3