Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Dietary sugar intake may increase insulin production, stress the beta cells and increase the risk for islet autoimmunity (IA) and subsequent type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Since 1993, the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) has followed children at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes for the development of IA (autoantibodies to insulin, GAD or protein tyrosine phosphatase-like protein [IA2] twice or more in succession) and progression to type 1 diabetes. Information on intake of fructose, sucrose, total sugars, sugar-sweetened beverages, beverages with non-nutritive sweetener and juice was collected prospectively throughout childhood via food frequency questionnaires (FFQs). We examined diet records for 1,893 children (mean age at last follow-up 10.2 years); 142 developed IA and 42 progressed to type 1 diabetes. HLA genotype was dichotomised as high risk (HLA-DR3/4,DQB1*0302) or not. All Cox regression models were adjusted for total energy, FFQ type, type 1 diabetes family history, HLA genotype and ethnicity.

Results

In children with IA, progression to type 1 diabetes was significantly associated with intake of total sugars (HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.07–2.85). Progression to type 1 diabetes was also associated with increased intake of sugar-sweetened beverages in those with the high-risk HLA genotype (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.25–2.71), but not in children without it (interaction p value = 0.02). No sugar variables were associated with IA risk.

Conclusions/interpretation

Sugar intake may exacerbate the later stage of type 1 diabetes development; sugar-sweetened beverages may be especially detrimental to children with the highest genetic risk of developing type 1 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus is an autoimmune disease with a preclinical phase during which the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas are destroyed. Both genetic and environmental factors influence the autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells. The HLA-DR,DQ alleles are the strongest known genetic factor driving type 1 diabetes risk. Environmental factors such as excessive insulin demand and increased insulin production may accelerate type 1 diabetes development by increasing beta cell apoptosis [1], and making the beta cell more active and thus more vulnerable to autoimmune attack [2].

The Overload Hypothesis proposes a mechanism relating beta cell stress to type 1 diabetes development, suggesting that overeating and sedentary lifestyles place a high insulin demand on the beta cell [3]. Rapidly digested foods, such as refined carbohydrates, can cause large postprandial spikes in blood glucose and a higher rate of insulin production [4]. Researchers have investigated a variety of dietary factors that may increase insulin demand for their role in islet autoimmunity (IA) and type 1 diabetes risk, including total energy intake [5], carbohydrate intake [5, 6], glycaemic load and glycaemic index of the diet [7], mono- and disaccharides [5, 6] and sucrose [5].

Previously, we showed that a higher glycaemic index was associated with increased type 1 diabetes risk in children with IA [7], but not with the development of IA. Here, we expand the analysis to examine specific forms of sugar (fructose and sucrose), total carbohydrates and sugars, and major dietary sources of sugars, such as sugar-sweetened beverages and juice. Using prospective data from a population of children with increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes, we explored childhood sugar intake for association with IA development, and with subsequent type 1 diabetes development in children with IA.

Our primary hypothesis is that increased sugar intake increases risk of type 1 diabetes in children with IA. We also explored gene–environment interactions between a child’s HLA-DR,DQ genotype and sugar intake for association with IA and type 1 diabetes risk.

Methods

The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) is a prospective study of two groups of young children at increased risk for developing type 1 diabetes. One group consists of unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes, identified and recruited generally between birth and age 4 years. The second group consists of babies born at St Joseph’s Hospital in Denver, CO, USA, and screened at birth for diabetes-susceptibility alleles in the HLA-DR,DQ alleles. This group is representative of the general population of the Denver Metropolitan Area. The details of the newborn screening [8] and follow-up [9] have been published elsewhere. DAISY has enrolled 2,547 children at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes from 1993 to 2006.

Prospective follow-up of DAISY children included clinic visits at 9, 15 and 24 months (if child enrolled at birth) or at enrolment visit (if child enrolled later in childhood), and annually thereafter [8]. At every visit, blood was drawn and tested for insulin autoantibody (IAA) and autoantibodies to protein tyrosine phosphatase-like protein (IA2) and GAD using radioimmunoassays, as described previously [10–12]. The cut-off for positivity was established as the 99th percentile of healthy controls. If a child was determined to be autoantibody positive, he or she was put on an accelerated schedule, with a visit every 3–6 months. IA was defined as testing positive for ≥ 1 autoantibody on two consecutive visits, or being autoantibody positive on one visit and diabetic on the next consecutive visit. A child was referred to a physician for type 1 diabetes diagnosis if they had a random glucose > 11.1 mmol/l and/or an HbA1c > 6.2% (44 mmol/mol). The criteria used for type 1 diabetes diagnosis included typical symptoms of polyuria and/or polydipsia and a random glucose > 11.1 mmol/l or an OGTT with a fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/l or 2 h glucose > 11.1 mmol/l. The details of the intensive monitoring and type 1 diabetes diagnosis protocol have been described previously [13]. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols. Informed consent was obtained from the parents/legal guardians of all children. Assent was obtained from children aged 7 years and older.

A semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (Nutrition Questionnaire Service Center, Boston, MA, USA) was used to record the child’s diet via parental report. This FFQ has been validated using multiple 24 h recalls and biomarkers in the DAISY population [14, 15]. Parents completed the FFQ regarding their child’s diet over the course of the past year, beginning at age 2 years, and annually thereafter. Dietary data were linked to an autoantibody measurement if the 1 year time period of the questionnaire encompassed the time directly preceding the visit at which the autoantibody was measured. Cases of IA and type 1 diabetes that developed prior to age 1 year were not included in the analyses as FFQs were not completed before 1 year of age.

On the FFQ, food intake is classified into nine response categories ranging from ‘never or less than once per month’ to ‘6+ times per day’. The average daily intake was calculated by multiplying each item’s consumption frequency by its nutrient content and summing the nutrient contributions of all foods. Starting in 2003, DAISY began sending a Youth Adolescent Questionnaire (YAQ) to children aged 10 years or older, so that these older children could report their own diets [16]. The 152 question YAQ is based on the 145 question FFQ. The YAQ was designed to be user-friendly for adolescents and has been both validated against 24 h diet recalls and shown to be reproducible in this age group [17, 18]. A comparison of the FFQ and the YAQ in the DAISY population showed that diet data from the FFQ and the YAQ can be used in the same analysis if the analysis includes an indicator variable defining the survey type with which a nutrient was collected [16]. FFQs and YAQs were checked for plausibility of reported energy intake and completeness prior to analysis.

Nutrient values (daily average) for total energy, total carbohydrates, total sugars (glucose + fructose + lactose + sucrose + maltose), sucrose and ‘free’ fructose (not including the fructose in sucrose) were calculated from reported intakes. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (SR) release 10 was used to calculate nutrient values for the diet surveys collected from January 1996 to May 1999, SR release 11 from June 1999 to February 2003, SR release 14 from March 2003 to February 2007, SR release 19 from March 2007 to March 2011 and SR release 21 from April 2011 to present.

The frequency of consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (non-diet soda, sweetened iced tea, Hawaiian punch, lemonade, Kool-Aid or other non-carbonated fruit drink, Coke, caffeine-free Coke, Pepsi, caffeine-free Pepsi, other caffeinated/non-caffeinated cola with sugar, or other carbonated beverages with sugar), beverage sweetened with non-nutritive sweetener (diet soda, low-calorie cola/beverage with caffeine, caffeine-free low-calorie cola/beverage, other low-calorie carbonated beverage) and juice (orange juice, apple juice, grapefruit juice, prune juice and other fruit juice) were calculated by summing the reported consumption frequencies of each beverage in the group.

Analysis populations

For the analysis of the association between diet and IA development, we analysed multiple diet records per child prior to and including the first autoantibody-positive visit (in those who developed IA) or most recent follow-up (‘IA analysis cohort’). Prior to analysis, we excluded 648 DAISY participants because of missing childhood dietary data (n = 638) or missing ethnicity data (n = 10). Six children with IA were removed from the IA analysis cohort because of left-censoring (i.e. the child was IA positive at first DAISY clinic visit, making it impossible for us to know the time to IA development), but were included in the ‘type 1 diabetes analysis cohort’ (described below). We analysed 14,522 records for 1,893 DAISY children with complete data for the development of IA; 139 of these children developed IA.

For the analysis of diet and the progression to type 1 diabetes in children with IA, there were 145 IA-positive children with complete data. We excluded three children whose age at first autoimmunity was within 3 months of type 1 diabetes development because of concerns regarding the effect the disease may have had on the diet at the late preclinical stage. We examined a single dietary measure corresponding to the age at first IA-positive visit for the 142 children who developed IA (‘type 1 diabetes analysis cohort’). Forty-two children in the type 1 diabetes analysis cohort subsequently developed type 1 diabetes (Fig. 1).

Flowchart of the IA analysis and type 1 diabetes analysis cohorts. aTen children were excluded from both cohorts due to lack of ethnicity data. bSix children were excluded from the IA analysis cohort, because they were IA positive at their first clinic visit, and there was no measure of when they actually developed IA. These six children were included in the type 1 diabetes analysis cohort. cThree children were excluded from the type 1 diabetes analysis cohort as their age at first autoimmunity was within 3 months of type 1 diabetes development and we were concerned about the effect the disease may have had on the diet at the late preclinical stage

While DAISY continued to collect FFQs after the appearance of IA, we did not analyse these longitudinal data for progression to type 1 diabetes for the following reasons. Children with IA had clinic visits every 3 months, but the FFQ was collected annually, meaning that data from a single FFQ could be applied to up to four clinic visits, seriously restricting the time-varying nature of the diet data. Also, when a child was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, we did not contact the family after diagnosis to collect an FFQ because the intense dietary advice they receive at diagnosis may alter their recollection of the child’s pre-diagnosis diet. Thus, we did not have diet information corresponding to up to 1 year before diagnosis for some of the children who developed type 1 diabetes, greatly reducing our ability to examine the effect of diet just before diagnosis in all children. Finally, an analysis of diet at the first indication of autoimmunity would be least affected by the possibility that increased sugar intake may be a result of increasingly compromised beta cell function and/or increased craving for sugars in those who are closest to clinical onset of disease (i.e. reverse causation).

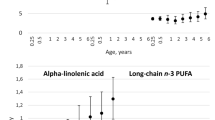

In order to determine the appropriateness of investigating diet at first IA positivity for association with type 1 diabetes risk, we explored the variation of the total sugars and sugar-sweetened beverage variables in the IA period. Reported dietary intakes were adjusted for total energy intake and type of FFQ using the residual method [19]; mean total sugar intake (Fig. 2a) and sugar-sweetened beverage intake (Fig. 2b) were then calculated for each year of follow-up in the IA period for IA-positive children, separately for those who developed and did not develop type 1 diabetes (by HLA-DR3/4,DQB1*0302 status). Total sugar intake was relatively stable in the autoimmune period (Fig. 2a), while sugar-sweetened beverages showed an increase in children with the longest follow-up, likely reflecting an increase in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in older children (Fig. 2b); the relationship between intake in those who eventually did and did not develop type 1 diabetes was consistent during this period. The stability and consistency of relationship of the intake in the autoimmune period, combined with the reporting and inference issues described above, led us to define dietary exposure as fixed variables at the age of the first autoantibody-positive visit for the analysis of the type 1 diabetes outcome, which provided the most complete representation of dietary intake during this time period and was least likely to be influenced by the disease process.

Mean dietary intake of (a) total sugars and (b) sugar-sweetened beverage by year of follow-up in the autoimmune period for three groups: children who developed type 1 diabetes and had the high-risk HLA genotype (squares); children who developed type 1 diabetes and did not have the high-risk HLA genotype (triangles); and children who did not develop type 1 diabetes (circles). Data points with sample sizes <5 are not displayed

Statistical analyses

The statistical software package SAS, version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), was used for all statistical analyses. For all analyses, HRs and 95% CIs were estimated using Cox regression to account for right-censored data. A clustered time-to-event analysis was performed, treating siblings from the same family as clusters, and robust sandwich variance estimates [19] were used for statistical inference.

For the analyses of time to development of IA, the diet variables were treated as time-varying covariates, and we adjusted for the HLA-DR,DQ genotype (HLA-DR3/4,DQB1*0302 vs all other genotypes), type 1 diabetes family history, ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs other), diet survey type (FFQ or YAQ) and total energy. We analysed the nutrients that represent sugar intake (fructose, sucrose, total carbohydrates and total sugars), as well as the intake frequencies of sugar-sweetened beverages, beverages sweetened with non-nutritive sweetener, and juice. We did not analyse lactose as this diet variable was included in a previous analysis of cow’s milk intake [20]. Each diet variable was tested in a separate model. The HRs were calculated for an SD difference in sugars or beverage intake.

For the analysis of progression to type 1 diabetes in IA-positive children, the diet variables corresponding to the time at first IA positivity were treated as fixed covariates, and we adjusted for age at first IA positivity in addition to HLA-DR,DQ genotype (HLA-DR3/4,DQB1*0302 vs all other genotypes), type 1 diabetes family history, ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs other), diet survey type (FFQ or YAQ) and total energy.

Based on our a priori hypotheses, we then tested the significance of an interaction between each diet variable and HLA-DR,DQ genotype. Interaction models contained the base terms (e.g. fructose intake and HLA-DR,DQ genotype) and an interaction term (e.g. fructose intake × HLA-DR,DQ genotype). To reduce false positives, we defined significant effect modification of diet by HLA as having to meet two criteria: (1) the Wald p value of the diet × HLA interaction term is < 0.05; and (2) the association between diet and outcome is statistically significant (p < 0.05) in at least one of the HLA-DR,DQ genotype strata. All diet variables were treated as continuous variables in the interaction terms.

Results

Sugar intake and development of IA

The IA analysis cohort was 48% female, 76% non-Hispanic white and followed for an average of 10.2 years. DAISY children who developed IA were significantly more likely to have the high-risk HLA-DR,DQ genotype than those who did not develop IA, and were more likely to have a family history of type 1 diabetes (Table 1). None of the sugar intake variables that we investigated were associated with IA development (Table 2); also, HLA-DR,DQ genotype did not modify the effect of the sugar intake variables on the risk of IA development in the IA analysis cohort.

Sugar intake and progression to type 1 diabetes in children with IA

The type 1 diabetes analysis cohort was 49% female and 77% non-Hispanic white. Children with IA who developed type 1 diabetes were younger at IA development, and were significantly more likely to have the high-risk HLA-DR,DQ genotype or be non-Hispanic white compared with children with IA who did not develop type 1 diabetes (Table 3). Total sugar intake was significantly associated with an increased risk of progression to type 1 diabetes in children with IA (Table 4). We also identified a significant interaction between sugar-sweetened beverage intake and HLA-DR,DQ genotype (interaction p value = 0.02). Specifically, increased sugar-sweetened beverage intake was significantly associated with type 1 diabetes development in children with IA who had high genetic risk for type 1 diabetes, but not in children with IA who had low/moderate genetic risk for type 1 diabetes (Table 4). No other sugars variables demonstrated a significant effect modification by HLA genotype in the association with type 1 diabetes risk.

Discussion

This prospective analysis of children at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes is a follow-up of a previous analysis in the DAISY cohort in which dietary glycaemic index was found to be associated with type 1 diabetes risk [7]. This follow-up analysis investigates in detail which nutrients and sugar-containing foods most strongly influence IA and type 1 diabetes risk. The results suggest that sugar intake may not affect the early stage of the type 1 diabetes disease process, prior to IA development. However, once the immune system has been activated by other genetic or environmental factors and the body has begun the autoimmune attack on the beta cells, the total amount of sugar that a child consumes may increase type 1 diabetes risk.

Our results show that a higher total sugar intake increases a child’s risk of progressing to type 1 diabetes once they develop IA, regardless of HLA genotype. Two previous case–control studies have also suggested that sugar intake may play a role in type 1 diabetes development. Dahlquist et al found an association between intake of carbohydrate, as well as mono- and disaccharides, and type 1 diabetes risk [6]. A more recent Swedish study also found that carbohydrates, and in particular, disaccharides and sucrose, were associated with type 1 diabetes risk [5]. While our study did not find a significant association between sucrose or carbohydrates and type 1 diabetes risk specifically, our prospective cohort study results generally support these case–control reports.

The association between increased total sugars consumption and more rapid type 1 diabetes progression in children with IA may be driven by direct or indirect biological mechanisms. Sugar may be toxic to the beta cell, and intermittent exposure to high levels of dietary sugars may directly induce beta cell apoptosis and reduce normal beta cell proliferation [21]. Similarly, frequent hyperglycaemic episodes may increase cytokine toxicity and oxidative stress, which may increase beta cell apoptosis [21, 22]. Alternatively, greater sugar intake may indirectly speed type 1 diabetes development due to the resulting greater insulin demand, overloading the beta cell that is already under autoimmune attack. This beta cell overload may accelerate beta cell apoptosis by making the beta cell more active and thus more visible to the immune system [23, 24], possibly upregulating the autoimmune attack [3, 25]. It is also possible that increased sugar intake is the result, and not the cause, of an already compromised beta cell function, via increased craving for sugars. Our focus on dietary intake early in the autoimmune period (i.e. at the time of first IA positivity) and removal of all diet data collected within 3 months prior to type 1 diabetes diagnosis should largely eliminate this effect.

Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption was associated with increased risk of progression to type 1 diabetes in children, but only in children possessing the high-risk HLA-DR,DQ genotype. Sugar-sweetened beverages have been explored for their association with type 1 diabetes risk in other studies, with varying results. A Swedish study found no association between soft drink intake and type 1 diabetes risk [5], while a Canadian case–control study identified a dose–response association between soft drink consumption and type 1 diabetes risk [26]. Neither study had HLA-DR,DQ genotype information available. Our results align with another study that found the introduction of sugar-sweetened beverages in the first year of life was associated with an earlier age at type 1 diabetes diagnosis, independent of HLA-DR,DQ genotype [27].

Our observation that sugar-sweetened beverages negatively affect the children at the very highest risk of developing type 1 diabetes may suggest that the genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes is exacerbated by this particular dietary exposure. Alternatively, it may be easier to see the association between sugar-sweetened beverages and type 1 diabetes risk only in the highest-risk children, because sugar-sweetened beverages are not consumed as frequently or in as great a quantity as total sugars, and do not completely represent sugar intake. Finally, we note that this interaction between sugar-sweetened beverages and genetic type 1 diabetes risk may reflect other, unmeasured, lifestyle factors related to sugar-sweetened beverage intake.

We did not find an association between fruit juice consumption and either IA development or progression to type 1 diabetes, despite high-sugar fruit juices being consumed more frequently than sugar-sweetened beverages in our cohorts (shown in Tables 1 and 3). A Canadian study also did not find an association between fruit juice and type 1 diabetes risk [26]. The lack of association between fruit juice and either IA or type 1 diabetes risk may reflect that fruit juice, while having a high sugar content, often contains components that benefit health, and also may have fewer artificial components, thus making it a complicated food by which to measure the effects of sugar.

In agreement with our hypothesis and previous findings in the DAISY cohort [7], we did not find significant associations between any of the sugars variables examined and IA risk. Due to the subclinical nature of the IA outcome, very few studies have been able to examine dietary risk factors for IA development. Virtanen et al found no association between sweet and sugar consumption and risk of advanced beta cell autoimmunity [28]. It is possible that these dietary factors do not initiate the autoimmune process, but may only exacerbate an autoimmune process that has already begun.

The strengths of this study include the availability of HLA-DR,DQ genotype information and the prospective longitudinal nature of the data collection at frequent intervals, with monitoring for both the appearance of IA and progression to type 1 diabetes in the same cohort. Our analysis was limited by the structure of the FFQs, which at the time of collection did not separate out added sugars or distinguish between high-fructose corn syrup and fructose from fruit and fruit juice. We also could not estimate starch consumption from the available dietary data. Also, while the semi-quantitative FFQ suggested portion sizes for all beverages, it did not specify the number of ounces or grams in a portion, thus limiting our ability to quantify beverage intakes. The FFQ (and YAQ) data are inherently limited by being self-reported and by the long time period (1 year) over which we asked an individual to report dietary intake. Finally, the DAISY cohort was selected for having increased genetic risk of developing type 1 diabetes, and therefore our results are not generalisable to the US paediatric population.

Sugar intake may influence the later stage of the type 1 diabetes development process, and genetic factors may interact with dietary factors to exacerbate type 1 diabetes disease risk. These results suggest that dietary changes may delay or prevent type 1 diabetes development in a child with IA. Future studies should collect and examine more detailed dietary data, especially on all forms of carbohydrates, in order to confirm and expand these findings and to aid the design of potential intervention studies.

Abbreviations

- DAISY:

-

Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- IA:

-

Islet autoimmunity

- IA2:

-

Protein tyrosine phosphatase-like protein

- IAA:

-

Insulin autoantibody

- SR:

-

Standard reference

- YAQ:

-

Youth Adolescent Questionnaire

References

Eizirik DL, Darville MI (2001) β-Cell apoptosis and defense mechanisms: lessons from type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 50:S64–S69

Velloso LA, Bjork E, Ballagi AE et al (1994) Regulation of GAD expression in islets of Langerhans occurs both at the mRNA and protein level. Mol Cell Endocrinol 102:31–37

Dahlquist G (2006) Can we slow the rising incidence of childhood-onset autoimmune diabetes? The overload hypothesis. Diabetologia 49:20–24

Ludwig DS (2002) The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 287:2414–2423

Pundziute-Lycka A, Persson LA, Cedermark G et al (2004) Diet, growth, and the risk for type 1 diabetes in childhood: a matched case-referent study. Diabetes Care 27:2784–2789

Dahlquist GG, Blom LG, Persson LA, Sandstrom AI, Wall SG (1990) Dietary factors and the risk of developing insulin dependent diabetes in childhood. BMJ 300:1302–1306

Lamb MM, Yin X, Barriga K et al (2008) Dietary glycemic index, development of islet autoimmunity, and subsequent progression to type 1 diabetes in young children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3936–3942

Rewers M, Bugawan TL, Norris JM et al (1996) Newborn screening for HLA markers associated with IDDM: Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). Diabetologia 39:807–812

Norris JM, Barriga K, Klingensmith G et al (2003) Timing of initial cereal exposure in infancy and risk of islet autoimmunity. JAMA 290:1713–1720

Yu L, Rewers M, Gianani R et al (1996) Antiislet autoantibodies usually develop sequentially rather than simultaneously. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:4264–4267

Barker JM, Barriga KJ, Yu L et al (2004) Prediction of autoantibody positivity and progression to type 1 diabetes: Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:3896–3902

Yu L, Robles DT, Abiru N et al (2000) Early expression of antiinsulin autoantibodies of humans and the NOD mouse: evidence for early determination of subsequent diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:1701–1706

Stene LC, Barriga K, Hoffman M et al (2006) Normal but increasing hemoglobin A1c levels predict progression from islet autoimmunity to overt type 1 diabetes: Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). Pediatr Diabetes 7:247–253

Parrish LA, Marshall JA, Krebs NF, Rewers M, Norris JM (2003) Validation of a food frequency questionnaire in preschool children. Epidemiology 14:213–217

Brady HL, Lamb MM, Sokol RJ et al (2007) Plasma micronutrients are associated with dietary intake and environmental tobacco smoke exposure in a paediatric population. Public Health Nutr 10:712–718

Lamb MM, Ross CA, Brady HL, Norris JM (2007) Comparison of children’s diets as reported by the child via the Youth/Adolescent Questionnaire and the parent via the Willett food-frequency questionnaire. Public Health Nutr 10:663–670

Rockett HR, Breitenbach M, Frazier AL et al (1997) Validation of a youth/adolescent food frequency questionnaire. Prev Med 26:808–816

Rockett HR, Wolf AM, Colditz GA (1995) Development and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of older children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 95:336–340

Wei LJ, Lin DY, Weissfeld L (1989) Regression analysis of multivariate incomplete failure time data by modeling marginal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc 84:1065–1073

Lamb MM, Miller M, Seifert JA et al (2015) The effect of childhood cow’s milk intake and HLA-DR genotype on risk of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young. Pediatr Diabetes 16:31–38

Zhang Z, Li J, Yang L et al (2014) The cytotoxic role of intermittent high glucose on apoptosis and cell viability in pancreatic beta cells. J Diabetes Res 2014:712781

Mandrup-Poulsen T (1996) The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of IDDM. Diabetologia 39:1005–1029

Aaen K, Rygaard J, Josefsen K et al (1990) Dependence of antigen expression on functional state of beta-cells. Diabetes 39:697–701

Buschard K, Brogren CH, Ropke C, Rygaard J (1988) Antigen expression of the pancreatic beta-cells is dependent on their functional state, as shown by a specific, BB rat monoclonal autoantibody IC2. APMIS 96:342–346

Bjork E, Kampe O, Karlsson FA et al (1992) Glucose regulation of the autoantigen GAD65 in human pancreatic islets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 75:1574–1576

Benson VS, Vanleeuwen JA, Taylor J, McKinney PA, van Til L (2008) Food consumption and the risk of type 1 diabetes in children and youth: a population-based, case-control study in Prince Edward Island, Canada. J Am Coll Nutr 27:414–420

Crume TL, Crandell J, Norris JM et al (2014) Timing of complementary food introduction and age at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH nutrition ancillary study (SNAS). Eur J Clin Nutr 68:1258–1260

Virtanen SM, Nevalainen J, Kronberg-Kippila C et al (2012) Food consumption and advanced β cell autoimmunity in young children with HLA-conferred susceptibility to type 1 diabetes: a nested case-control design. Am J Clin Nutr 95:471–478

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-DK49654, DK32493, DK32083, DK50979 and the Diabetes Endocrine Research Center, Clinical Investigation & Bioinformatics Core P30 DK 57516.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

MML analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All other authors reviewed/edited the manuscript. BF and JAS assisted with data collection and analysis. MK designed the statistical analysis. MR contributed to study conception and design. JMN assisted with study design and analysis design and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript. MML has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lamb, M.M., Frederiksen, B., Seifert, J.A. et al. Sugar intake is associated with progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes: the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young. Diabetologia 58, 2027–2034 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3657-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3657-x