Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The influence of glucagon on glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes is debated. We investigated the relationship between postprandial glucagon levels and HbA1c during a period up to 60 months after diagnosis of childhood type 1 diabetes.

Methods

The Danish remission phase cohort comprised 129 children (66 boys) with type 1 diabetes whose mean (SD) age at onset was 10.0 (3.9) years. Liquid mixed-meal tests were performed prospectively at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months and a subset of 40 patients completed follow-up at 60 months. Postprandial (90 min) plasma levels of glucagon, glucose (PG), C-peptide, total glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and HbA1c were analysed. Multivariate regression (repeated measurements with all five visits included) was applied and results expressed as relative change (95% CI).

Results

Postprandial glucagon levels increased 160% from 1 to 60 months after diagnosis (p < 0.0001). A doubling in postprandial PG corresponded to a 21% increase in postprandial glucagon levels (p = 0.0079), whereas a doubling in total GLP-1 levels corresponded to a 33% increase in glucagon levels (p < 0.0001). Postprandial glucagon associated negatively with postprandial C-peptide (p = 0.017). A doubling in postprandial glucagon corresponded to a 3% relative increase in HbA1c levels (p = 0.0045).

Conclusions/interpretation

Postprandial glucagon levels were associated with deterioration of glycaemic control and declining beta cell function in the first 5 years after diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. The positive association of glucagon with total GLP-1 and PG suggests that physiological regulation of alpha cell secretion in type 1 diabetes is seriously disturbed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The main counter-regulatory hormone to insulin, glucagon, exerts important functions in maintaining glucose homeostasis. Glucagon regulates hepatic glucose production, enhancing glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. There is evidence that the production and secretion of glucagon is dependent upon a distinct hierarchy of complex mechanisms including pancreatic alpha cell signalling [1], beta cell signalling [2–5] and incretin hormones (glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1], glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide [GIP] and somatostatin) [6]. Furthermore, autonomic nervous system secretory products (adrenaline [epinephrine], growth hormone) [6, 7], autocrine signals (glutamate) [8] and acetylcholine [9] have been identified as having regulatory effects on glucagon release.

In healthy individuals, a fall in plasma glucose (PG) concentrations would result in a decrement in insulin secretion from the pancreatic beta cell and according to ‘the intra-islet insulin hypothesis’ [10] this decrement in circulating insulin indirectly regulates the pancreatic alpha cell and stimulates glucagon release. In the setting of beta cell depletion (type 1 diabetes), glucagon levels do not increase in the presence of hypoglycaemia [11–14] and, conversely, exaggerated glucagon levels are reported under hyperglycaemia [12, 15, 16]. Whether such hyperglucagonaemia is caused by abnormal PG levels, lack of intra-islet restraint by insulin on the alpha cell or other factors is presently unresolved. The presence of hyperglucagonaemia in type 1 diabetes and its potential role in glycaemic regulation is not well documented and there are no prospective studies in children addressing postprandial glucagon levels in long-standing type 1 diabetes.

We therefore investigated the changes in postprandial glucagon levels over time and their relationship to postprandial PG, C-peptide, total GLP-1, GIP and HbA1c in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes during a 5 year prospective follow-up.

Methods

Subjects

We included 129 children less than 17 years old, newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes according to the WHO’s criteria [17]. Children (all from the Danish remission phase cohort) were included on the day of diagnosis in the period 2004–2005 from four centres in Denmark. A liquid mixed-meal (Boost) test was performed at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after diagnosis (±1 week) and after 60 months in a subset of 40 patients. We evaluated the children for the presence of blood ketones before initiating the liquid mixed-meal test but none of the children had ketonaemia at the start of the procedure. A venepuncture was performed in the cubital vein and venous blood was sampled at the start of the procedure (fasting) for HbA1c and PG measurements at all visits. Capillary blood was drawn to measure capillary PG for validation. HbA1c was measured centrally at a laboratory that specialised in children with diabetes at the Department of Pediatrics, Herlev (formerly Glostrup) Hospital. Venous blood was collected 90 min after ingestion of liquid mixed-meal for measuring postprandial levels of glucagon, PG, C-peptide, total GLP-1 and GIP. A total of 12 (9%) participants had a single value missing for either glucagon, total GLP-1 or GIP at one visit only, whereas 117 (91%) patients contributed a complete set of hormone values at each respective visit during the first year. Causes for dropout at the year 5 visit were adolescents who had been transferred to adult clinics, change of residence and unwillingness to participate.

Procedures

The participants each ingested 6 ml/kg body weight (maximum 360 ml) of the liquid mixed-meal (Boost-Original; Novartis Medical Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at the respective visits. Each 237 ml (8 fl oz) serving of Boost contained 41 g carbohydrate, 10 g protein and 4 g fat—a total of 1,004 kJ (www.boost.com/nutritional-drinks/boost-original). The test was performed in the morning (between 07:00 hours and 09:00 hours) after an overnight fast (minimum 8 h), with no food or drink (except water) being taken after midnight the preceding night. Patients receiving insulin treatment via a pen omitted their dose of morning insulin (insulin glargine [A21Gly,B31Arg,B32Arg human insulin], insulin detemir [B29Lys(ε-tetradecanoyl),desB30 human insulin], neutral protamine Hagedorn [NPH] insulin, pre-mixed insulin), including rapid-acting insulins, from midnight prior to examination. Insulin pump users paused insulin administration (and removed the pump) 2 h before baseline without using rapid-acting insulin bolus after midnight prior to examination. Venous and capillary blood was drawn at the start of the procedure and again 90 min after liquid mixed-meal ingestion as previously described [18].

HbA1c measurement

HbA1c was analysed centrally using a high-pressure liquid chromatographic method (normal range 4.3–5.8% [23–40 mmol/mol]); Tosoh Bioscience, South San Francisco, CA, USA) as described previously [19].

C-peptide, glucagon, GLP-1 and GIP

C-peptide was measured by a fluoroimmunometric assay [15]. Partial remission was defined as postprandial (stimulated) C-peptide >300 pmol/l. Glucagon, total GLP-1 and GIP were measured as described previously [15, 18]. The glucagon assay was recently validated and is directed at the C-terminus of the molecule. It shows little or no cross-reaction with other known substances, except in severe renal insufficiency, and has an intra-assay coefficient of variation of <6% and a sensitivity of <1 pmol/l [20, 21].

Ketoacidosis and hypoglycaemia

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) was defined as blood glucose >11 mmol/l (~200 mg/dl), ketonuria and/or ketonaemia, venous pH < 7.30 and standard bicarbonate <15 mmol/l [22, 23]; severe DKA was defined as venous pH < 7.10 and standard bicarbonate <5 mmol/l. Severe hypoglycaemia was defined as hypoglycaemic events leading to loss of consciousness and/or seizure [24].

Ethics

The study was performed according to the Helsinki II Declaration (as revised in 2008) and was approved by the local ethics committee (project number: H-KA-04010-M). All patients and parents gave their informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Statistical methods

Continuous responses were summarised by geometric means (95% CIs). Logistic regression models for ordinal measures were used to estimate p values. Logarithmic values of responses were analysed by multivariate linear regression accounting for intra-person correlation. Estimated effects were expressed as relative changes (95% CIs). All relevant explanatory variables were included in the initial model as well as combined effects of relevant hormones and visits. As all children were included at the day of diagnosis and followed at the same predefined time points, diabetes duration did not have an individual effect on the outcome variables. This variable was therefore omitted from the analyses, and the variable ‘visit’ was used as a proxy for diabetes duration and evaluated as a continuous response. Model reduction was accomplished by backwards elimination with a 5% cut-off value. Logarithmic values were back-transformed and expressed as mean (95% CI). Clinical characteristics of the cohort (continuous variables) (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1) were not normally distributed, but mean and median values did not differ significantly and they were therefore expressed as mean ± SD.

Specifically, we estimated the effect of the respective postprandial hormones (C-peptide, total GLP-1, GIP) and PG, as well as HbA1c, on postprandial glucagon levels (as the dependent variable). Second, we quantified the relationship between HbA1c (as dependent variable) and glucagon (explanatory variable) and vice versa and tested relevant explanatory variables (hormones and PG effect and their change over time, insulin dose [U kg−1 day−1] and BMI [kg/m2]) in the model. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The mean (SD) age of the cohort (66/129 [51.2%] boys) was 10.0 ± 3.9 (range 0.6–16.6) years at the time of diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (Table 1). Altogether, 15% of the children had DKA and, out of these, 2% had severe DKA at disease onset (four patients had missing data for DKA, Table 1). Of the 129 patients, 7.5% had one or more episodes of severe hypoglycaemia during the first year of follow-up. The proportion of children in partial remission (postprandial C-peptide >300 pmol/l) was 71% at 6 months, 48% at 12 months and 5% at 60 months (Table 1).

The 40 patients (who completed follow-up at a diabetes duration of 5 years) were slightly younger, with a lower BMI, and had lower postprandial C-peptide levels 12 months after diagnosis compared with the full cohort, but they were similar in terms of sex distribution, HbA1c and hormone levels (ESM Table 1). In this subgroup, 13% of the children had DKA at diagnosis (one patient with missing data; none had severe DKA). Of these 40 patients followed for 5 years, 8.5% had one or more episodes of severe hypoglycaemia.

Changes in postprandial hormone levels over time

The levels of HbA1c, postprandial levels of glucagon, PG, C-peptide, total GLP-1 and GIP during the 5 years are illustrated in Fig. 1. All hormone concentrations increased significantly after ingestion of the liquid mixed-meal at the 60 month visit (vs fasting concentrations, ESM Table 2). During the study period, alpha cell function assessed by (postprandial) glucagon levels increased by 51% from the first to the 12 month visit after diagnosis (relative change 1.51 [95% CI 1.36, 1.68]) whereas a 160% increase was observed over the entire study period from 1 to 60 months after onset (relative change 2.60 [2.24, 3.10], Fig. 1a, p < 0.0001). PG levels (Fig. 1b) increased by 38% from 1 to 12 months (relative change 1.38 [1.30, 1.46]) and by 68% from 1 to 60 months (relative change 1.68 [1.55, 1.81], Fig. 1b, p < 0.0001). The change in HbA1c during the first year after onset of diabetes was characterised by a steep decrease from 1 to 3 months, with HbA1c reaching a nadir at 3 months; thereafter, a steady increase occurred as expected (Fig. 1c). The decrement in C-peptide was most pronounced during the first year; C-peptide levels decreased 62% from 1 to 12 months (relative change 0.38 [0.32, 0.45]) and a 93% decrease was observed in the period from 1 to 60 months after diagnosis (relative change 0.07 [0.06, 0.09], Fig. 1d, p < 0.0001). Total GLP-1 levels increased by 11% from 1 to 12 months (relative change 1.11 [1.03, 1.20]) and an insignificant 10% increase was observed over the entire study period from 1 to 60 months (relative change 1.10 [0.96, 1.26], Fig. 1e, p = 0.15). GIP levels increased 14% from 1 to 12 months (relative change 1.14 [1.06, 1.23]) but a 34% decrease was observed from 1 to 60 months of diabetes duration (relative change 0.66 [0.58, 0.75], p < 0.0001). Fasting and postprandial glucagon levels at the 5 year visit were highly correlated (Spearman test for correlation 0.81 [SD 0.65], p < 0.0001).

Time course of changes (mean [SD]) in HbA1c (c), and postprandial (90 min) levels of glucagon (a), PG (b), C-peptide (d), total GLP-1 (e) and GIP (f). Data are expressed as mean (95% CI). Solid line, whole cohort (N = 129); dotted line, patients (n = 40) who completed follow-up at 60 months. To convert values for HbA1c from mmol/mol (IFCC) to % (DCCT), please use the conversion HbA1c (DCCT) = [0.09148 × HbA1c (IFCC)] + 2.152

Factors affecting glucagon

We analysed postprandial levels of hormones and other predictors with an overall effect on postprandial glucagon levels. All substrate (repeated) measurements were included in the model and the result of the final reduced model is reported (adjusted for age, sex and C-peptide). Glucagon levels were not associated with BMI (p > 0.5), although they were positively associated with age at onset (p = 0.03) and male sex (p = 0.003). Furthermore, glucagon levels correlated highly with postprandial PG (p < 0.0001) and total GLP-1 (p < 0.0001) and a negative correlation existed with C-peptide (p = 0.017). In quantitative terms, we found that a doubling in postprandial PG was associated with a 21% rise in glucagon levels (relative change 1.21 [1.05, 1.40]). A doubling in total GLP-1 levels was associated with a 33% increase in glucagon (relative change 1.33, [1.20, 1.48]) over the study entire period. C-peptide levels were inversely correlated with glucagon levels, with varying effect, with disease duration (interaction of C-peptide × visit, p = 0.017). A 50% reduction in C-peptide levels was associated with a 6% increase in glucagon levels at 3 months (0.94 [0.89, 0.99]), a 9% increase at 6 months (0.91 [0.87, 0.95]) and a 5% increase at 12 months (0.95 [0.90, 0.99]) but no association existed at the 60 months visit (1.00 [0.93, 1.09]). Glucagon levels were not associated with GIP (p =0.39). Likewise, glucagon levels were not associated with either the daily exogenous insulin dose (U kg−1 day−1) (p = 0.39) or Δ (postprandial–fasting) PG levels (p = 0.08). Additionally, total GLP-1 levels were not correlated to PG levels (p = 0.21).

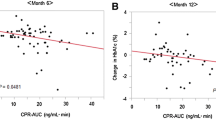

Glycaemic control and alpha cell function

We investigated the effect of various predictors on glycaemic control (assessed by HbA1c) with all substrate (postprandial) measurements at the respective visits included in the model (adjusted for age, sex and C-peptide). HbA1c was not associated with age at onset (p = 0.20) but correlated to male sex (rate ratio 0.96 [0.94, 0.99], p = 0.02). Furthermore, HbA1c was associated with glucagon levels (p = 0.0045) and a negative association was observed with C-peptide (p = 0.0004). In quantitative terms, a doubling in glucagon level corresponded with a 3% relative increase in HbA1c level (rate ratio 1.03 [1.01, 1.05]). The overall findings in this analysis did not change when excluding HbA1c values from the 1 month visit (which represents glycaemic control at the time of diagnosis). A 50% reduction in C-peptide level corresponded to a 5–6% increase in HbA1c, depending on the respective visit. We also evaluated whether the association with HbA1c levels (dependent variable) and glucagon was dependent upon the presence of residual beta cell function (postprandial C-peptide >300 pmol/l, representing children in partial remission). Therefore, we included the interaction for C-peptide × glucagon (C-peptide was dichotomised with a cut-off value of 300 pmol/l) in the model with HbA1c as the outcome variable. We found that the association with HbA1c and glucagon did not change when accounting for C-peptide (>300 pmol/l, p = 0.47). Total GLP-1 level was independent of C-peptide level (p = 0.97).

Discussion

This study of children with new-onset type 1 diabetes demonstrates a 160% increase in postprandial glucagon levels over a 5 year follow-up period. This progressive increase in postprandial glucagonaemia coincided with a marked reduction in residual beta cell function. Glucagon levels were dependent of age and sex, but not BMI or GIP. Moreover, glucagon levels associated positively with PG and also with total GLP-1 levels measured under a postprandial condition. Interestingly, glycaemic control assessed by HbA1c deteriorated proportionally with the progressive increase in glucagon over time.

We found that the subset of 40 patients who completed follow-up at a diabetes duration of 5 years had significantly lower postprandial C-peptide levels and BMI compared with the full cohort during follow-up. This discrepancy is probably because of their younger age at diabetes onset and is in accordance with a recent study reporting an association between low BMI and low stimulated C-peptide levels [18].

There was a significant increase in all hormone levels from the fasting to postprandial state 5 years after diagnosis, despite most patients (95%) being depleted of functioning beta cells at the time. One could argue that postprandial glucagon measurements are unreliable in the absence of fasting values, particularly in type 2 diabetes in which there is preserved residual beta cell function. A liquid mixed-meal stimulation test offers a more standardised method for assessing the role played by glucagon in postprandial hyperglycaemia, when repeated in the same patients according to weight, at the same time points after disease onset. The remaining beta cells under this procedure are challenged to the maximum limit and are influenced to a lesser extent by current PG prior to testing compared with fasting values. In addition, fasting and postprandial glucagon levels were highly correlated, which supports the argument that postprandial hormone measurements have the credibility needed to assess the role of glucagon in glycaemic control.

Prospective and cross-sectional studies in children with type 1 diabetes report that the observed postprandial hyperglucagonaemia worsens during the first year after diagnosis [12, 15] and also 3 years after onset [25], in agreement with our study. Notably, hyperglucagonaemia in response to liquid mixed-meal feeding is evidently established shortly after disease onset and seems to persist after several years with diabetes. It is of interest, that Kramer et al observed hyperglucagonaemia (in response to an oral glucose tolerance test) under both euglycaemic and hyperglycaemic conditions immediately prior to testing in patients with type 1 diabetes [26]. We tested the influence of insulin dose (included at all five visits) and found no overall effect of insulin dose on glucagon concentration, in agreement with the findings of Kramer et al [26].

Postprandial hyperglucagonaemia was strongly associated with glycaemic control (assessed by HbA1c) in the present study contrary to findings from the Hvidøre study (multicentre study representing 15 countries in Europe and Japan) [15] but in line with a recent Japanese study [25]. The discrepancy between our study and the Hvidøre study may be explained by the longer follow-up period with more frequent visits, and more children with absent beta cell function as a result of longer diabetes duration. The enhanced liquid mixed-meal stimulation with higher carbohydrate content in our study might also influence the observed differences between the two studies.

We observed unchanged GLP-1 concentrations and reductions in GIP concentrations measured in the postprandial state (Fig. 1 e, f) during the 5 year follow-up. Experimental studies indicate that intestinal L cells respond to luminal nutrients by secreting GLP-1 in a glucose-dependent manner [27, 28]. GLP-1 is furthermore reported to have glucagonostatic properties. It is therefore of interest, that GLP-1 was positively associated with glucagon in our cohort as also reported by others [15, 26]. This association of GLP-1 with glucagon is reported to persist during fasting [29]. It is well established that administration of GLP-1 and GLP-1 analogues suppresses glucagon release in type 1 diabetes [30, 31]. This association may indicate that the secretion of both GLP-1 and glucagon in type 1 diabetes is influenced by factors that outweigh their normal mutual interaction. In contrast, meal-related incretin (GLP-1 and GIP) responses are often diminished in type 2 diabetes [32] suggesting that different pathophysiological mechanisms are involved. In light of the recent development of GLP-1 analogues and dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors with glucagonostatic properties [31, 33, 34], add-on therapy combined with insulin could plausibly improve glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes [35].

GIP was recently reported to have glucagonotrophic effects [36, 37] and to protect against hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes [37]. This glucagonotrophic effect of GIP has been suggested to be mediated by GIP receptors present on the pancreatic alpha cells [38]. We could not find a convincing association between GIP and glucagon in the postprandial state. Our cohort had high fasting PG prior to liquid mixed-meal feeding, which may influence glucagon responses to GIP.

The strength of this study is the long follow-up period of over 5 years in a well characterised cohort of children newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. We aimed at describing hormone values after a standardised liquid mixed-meal and not under a fasting condition, but future studies should also include fasting values. Fasting hormone values would be valuable and add to the body of existing literature on alpha cell regulation. We cannot, owing to study design, tease out the factors with direct effect on the aberrant hyperglucagonaemia. More frequent sampling during the liquid mixed-meal would also be desirable, although a recent study in children found that a single 90 min hormone measurement is highly sensitive and offers an alternative to AUC analyses [39]. However, by performing only two venepunctures during the entire procedure we avoided unnecessary discomfort for the child. Comparisons across published studies are complicated though, due to differences in assay and stimulation tests, and consensus for standardisation is warranted. Our results do not address the question as to whether hyperglycaemia resulted in elevated levels of HbA1c and glucagon or whether the elevated glucagon augmented HbA1c and glucose levels. We can only provide information on associations and not causality in this clinical study. Further investigations of the physiology of alpha cell regulation in type 1 diabetes are needed.

In conclusion, this study provides data on the progressive worsening of postprandial hyperglucagonaemia in individuals with type 1 diabetes during the 5 years after onset of disease and suggests that pronounced endogenous insulin deficiency may be coupled to the observed hyperglucagonaemia although this relationship is not linear. The association of hyperglucagonaemia with GLP-1 and impaired glycaemic control suggests that GLP-1 in physiological doses is not sufficient to suppress glucagon. GLP-1 analogues as add-on therapy to insulin early in the course of type 1 diabetes should be investigated in further studies.

Abbreviations

- DKA:

-

Diabetic ketoacidosis

- GIP:

-

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- NPH:

-

Neutral protamine Hagedorn

- PG:

-

Plasma glucose

References

Walker JN, Ramracheya R, Zhang Q, Johnson PRV, Braun M, Rorsman P (2011) Regulation of glucagon secretion by glucose: paracrine, intrinsic or both? Diabetes Obes Metab 13(1):95–105

Samols E, Tyler JM, Mialhe P (1969) Suppression of pancreatic glucagon release by the hypoglycaemic sulphonylureas. Lancet 1:174–176

Maruyama H, Hisatomi A, Orci L, Grodsky GM, Unger RH (1984) Insulin within islets is a physiologic glucagon release inhibitor. J Clin Invest 74:2296–2299

Gromada J, Franklin I, Wollheim CB (2007) Alpha-cells of the endocrine pancreas: 35 years of research but the enigma remains. Endocr Rev 28:84–116

Braun M, Ramracheya R, Amisten S et al (2009) Somatostatin release, electrical activity, membrane currents and exocytosis in human pancreatic delta cells. Diabetologia 52:1566–1578

Taborsky GJ Jr, Ahrén B, Havel PJ (1998) Autonomic mediation of glucagon secretion during hypoglycemia: implications for impaired alpha-cell responses in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 47:995–1005

Marty N, Dallaporta M, Thorens B (2007) Brain glucose sensing, counterregulation, and energy homeostasis. Physiology Bethesda 22:241–251

Cabrera O, Jacques-Silva MC, Speier S et al (2008) Glutamate is a positive autocrine signal for glucagon release. Cell Metab 7:545–554

Molina J, Rodriguez-Diaz R, Fachado A, Jacques-Silva MC, Berggren P-O, Caicedo A (2014) Control of insulin secretion by cholinergic signaling in the human pancreatic islet. Diabetes 63:2714–2726

Hope KM, Tran POT, Zhou H, Oseid E, Leroy E, Robertson RP (2004) Regulation of alpha-cell function by the beta-cell in isolated human and rat islets deprived of glucose: the “switch-off” hypothesis. Diabetes 53:1488–1495

Banarer S, McGregor VP, Cryer PE (2002) Intraislet hyperinsulinemia prevents the glucagon response to hypoglycemia despite an intact autonomic response. Diabetes 51:958–965

Brown RJ, Sinaii N, Rother KI (2008) Too much glucagon, too little insulin: time course of pancreatic islet dysfunction in new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 31:1403–1404

Arbelaez AM, Xing D, Cryer PE et al (2014) Blunted glucagon but not epinephrine responses to hypoglycemia occurs in youth with less than 1 yr duration of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes 15:127–134

Sherr J, Xing D, Ruedy KJ et al (2013) Lack of association between residual insulin production and glucagon response to hypoglycemia in youth with short duration of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 36:1470–1476

Pörksen S, Nielsen LB, Kaas A et al (2007) Meal-stimulated glucagon release is associated with postprandial blood glucose level and does not interfere with glycemic control in children and adolescents with new-onset type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2910–2916

Sherr J, Tsalikian E, Fox L et al (2014) Evolution of abnormal plasma glucagon responses to mixed meal feedings in youth with type 1 diabetes during the first two years after diagnosis. Diabetes Care 37:1741–1744

World Health Organization (1999). Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO consultation. Part 1, Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66040. Accessed 15 Dec 2014

Andersen MLM, Nielsen LB, Svensson J et al (2014) Disease progression among 446 children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes located in Scandinavia, Europe, and North America during the last 27 yr. Pediatr Diabetes 15:345–354

Max Andersen MLC, Hougaard P, Pörksen S et al (2014) Partial remission definition: validation based on the insulin dose-adjusted HbA1c (IDAA1C) in 129 Danish children with new-onset type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 15:469–476

Bak MJ, Albrechtsen NW, Pedersen J et al (2014) Specificity and sensitivity of commercially available assays for glucagon and oxyntomodulin measurement in humans. Eur J Endocrinol 170:529–538

Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Hartmann B, Veedfald S et al (2014) Hyperglucagonaemia analysed by glucagon sandwich ELISA: nonspecific interference or truly elevated levels? Diabetologia 57:1919–1926

Dunger DB, Sperling MA, Acerini CL et al (2004) ESPE/LWPES consensus statement on diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child 89:188–194

Dunger DB, Sperling MA, Acerini CL et al (2004) European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology/Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society consensus statement on diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 113:e133–e140

Clarke W, Jones T, Rewers A, Dunger D, Klingensmith GJ (2008) Assessment and management of hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 9:165–174

Urakami T, Nagano N, Suzuki J, Yoshida A, Takahashi S, Mugishima H (2011) Influence of plasma glucagon levels on glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr 53:46–49

Kramer CK, Borgoño CA, van Nostrand P, Retnakaran R, Zinman B (2014) Glucagon response to oral glucose challenge in type 1 diabetes: lack of impact of euglycemia. Diabetes Care 37:1076–1082

Hansen L, Hartmann B, Mineo H, Holst JJ (2004) Glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion is influenced by perfusate glucose concentration and by a feedback mechanism involving somatostatin in isolated perfused porcine ileum. Regul Pept 118:11–18

Gribble FM, Williams L, Simpson AK, Reimann F (2003) A novel glucose-sensing mechanism contributing to glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from the GLUTag cell line. Diabetes 52:1147–1154

Vollmer K, Holst JJ, Baller B et al (2008) Predictors of incretin concentrations in subjects with normal, impaired, and diabetic glucose tolerance. Diabetes 57:678–687

Kielgast U, Holst JJ, Madsbad S (2011) Antidiabetic actions of endogenous and exogenous GLP-1 in type 1 diabetic patients with and without residual β-cell function. Diabetes 60:1599–1607

Kielgast U, Asmar M, Madsbad S, Holst JJ (2010) Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 on alpha- and beta-cell function in C-peptide-negative type 1 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:2492–2496

Toft-Nielsen MB, Damholt MB, Madsbad S et al (2001) Determinants of the impaired secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3717–3723

Ellis SL, Moser EG, Snell-Bergeon JK, Rodionova AS, Hazenfield RM, Garg SK (2011) Effect of sitagliptin on glucose control in adult patients with type 1 diabetes: a pilot, double-blind, randomized, crossover trial. Diabet Med 28:1176–1181

Foley JE, Ligueros-Saylan M, He Y-L et al (2008) Effect of vildagliptin on glucagon concentration during meals in patients with type 1 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 40:727–730

Kielgast U, Krarup T, Holst JJ, Madsbad S (2011) Four weeks of treatment with liraglutide reduces insulin dose without loss of glycemic control in type 1 diabetic patients with and without residual beta-cell function. Diabetes Care 34:1463–1468

Lund A, Vilsbøll T, Bagger JI, Holst JJ, Knop FK (2011) The separate and combined impact of the intestinal hormones, GIP, GLP-1, and GLP-2, on glucagon secretion in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300:E1038–E1046

Christensen M, Calanna S, Sparre-Ulrich AH et al (2014) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide augments glucagon responses to hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. doi:10.2337/db14-0440

De Heer J, Rasmussen C, Coy DH, Holst JJ (2008) Glucagon-like peptide-1, but not glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, inhibits glucagon secretion via somatostatin (receptor subtype 2) in the perfused rat pancreas. Diabetologia 51:2263–2270

Besser REJ, Shields BM, Casas R, Hattersley AT, Ludvigsson J (2013) Lessons from the mixed-meal tolerance test: use of 90-minute and fasting C-peptide in pediatric diabetes. Diabetes Care 36:195–201

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the children and their families participating in this study. We acknowledge our bioanalyst J. Høgsmose (Herlev Hospital) for expert handling of blood samples and data management. L. Albæk and S. Pilgaard (NNF Center for Basic Metabolic Research and Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Copenhagen) are thanked for expert hormone analyses.

Duality of interest

JS has received lecture funding from Novo Nordisk and Sanofi Aventis and is part of the Bayer Advisory Board. JS and LH are stock and shareholders in Novo Nordisk. All other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with their contribution to this manuscript.

Contribution statement

SF, HBM and JS made substantial contribution to conception and design of the study. SF, MLMA, SP, JJH, JJ and JT were responsible for acquisition of data. JJH was responsible for generation of data and SF, CP, LH, LBN, HBM and JS analysed and interpreted data. SF drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version. SF and JS are the guarantors for this work and take full responsibility for the authenticity of the reported data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(PDF 14 kb)

ESM Table 2

(PDF 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fredheim, S., Andersen, ML.M., Pörksen, S. et al. The influence of glucagon on postprandial hyperglycaemia in children 5 years after onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 58, 828–834 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3486-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3486-3