Abstract

Background

Mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients is affected by multiple variables. The possible impact of the mode of ventilation has not yet been clarified; therefore, a secondary analysis of the “epidemiology of sepsis in Germany” study was performed. The aims were (1) to describe the ventilation strategies currently applied in clinical practice, (2) to analyze the association of the different modes of ventilation with mortality and (3) to investigate whether the ratio between arterial partial pressure of oxygen and inspired fraction of oxygen (PF ratio) and/or other respiratory variables are associated with mortality in septic patients needing ventilatory support.

Methods

A total of 454 ICUs in 310 randomly selected hospitals participated in this national prospective observational 1-day point prevalence of sepsis study including 415 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock according to the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine criteria.

Results

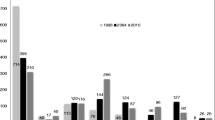

Of the 415 patients, 331 required ventilatory support. Pressure controlled ventilation (PCV) was the most frequently used ventilatory mode (70.6 %) followed by assisted ventilation (AV 21.7 %) and volume controlled ventilation (VCV 7.7 %). Hospital mortality did not differ significantly among patients ventilated with PCV (57 %), VCV (71 %) or AV (51 %, p = 0.23). A PF ratio equal or less than 300 mmHg was found in 83.2 % of invasively ventilated patients (n = 316). In AV patients there was a clear trend to a higher PF ratio (204 ± 70 mmHg) than in controlled ventilated patients (PCV 179 ± 74 mmHg, VCV 175 ± 75 mmHg, p = 0.0551). Multiple regression analysis identified the tidal volume to pressure ratio (tidal volume divided by peak inspiratory airway pressure, odds ratio OR = 0.94, 95 % confidence interval 95% CI = 0.89–0.99), acute renal failure (OR = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.01–4.55) and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.03–1.15) but not the PF ratio (univariate analysis OR = 0.998, 95 % CI = 0.995–1.001) as independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality.

Conclusions

This representative survey revealed that severe sepsis or septic shock was frequently associated with acute lung injury. Different ventilatory modes did not affect mortality. The tidal volume to inspiratory pressure ratio but not the PF ratio was independently associated with mortality.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Die Überlebenswahrscheinlichkeit von Patienten auf der Intensivstation wird von verschiedenen Faktoren beeinflusst. Der mögliche Einfluss der Beatmungsform auf die Sterblichkeit ist bis jetzt nicht ausreichend untersucht worden. Daher wurde eine Sekundäranalyse der „Prävalenz der Sepsis in Deutschland-Studie“ mit den Zielen durchgeführt, 1) die aktuelle Beatmungstherapie bei septischen Patienten zu beschreiben, 2) den Einfluss verschiedener Beatmungsformen auf die Sterblichkeit zu untersuchen und 3) herauszufinden, ob die Sterblichkeit der Patienten mit dem Horowitz-Index (HI, Quotient aus dem arteriellen Sauerstoffpartialdruck und der inspiratorischen Sauerstofffraktion) und/oder anderen respiratorischen Faktoren assoziiert ist.

Material und Methoden

An dieser nationalen, prospektiven, multizentrischen Observationsstudie nahmen 454 Intensivstationen von 310 zufällig ausgewählten Krankenhäusern teil. In die Studie wurden 415 Patienten, die die Kriterien einer schweren Sepsis oder eines septischen Schocks erfüllten, aufgenommen.

Ergebnisse

Es waren 331 der 415 teilnehmenden Patienten beatmungspflichtig. Druckkontrollierte Beatmung („pressure controlled ventilation“, PCV) war die am häufigsten benutzte Beatmungsform (70,6%), gefolgt von assistierter Spontanatmung („assisted ventilation“, AV; 21,7%) und volumenkontrollierter Beatmung („volume controlled ventilation“, VCV; 7,7%). Die Krankenhaussterblichkeit unterschied sich nicht signifikant zwischen PCV (57%), VCV (71%) und AV (51%; p = 0,23). Einen HI ≤300 mmHg zeigten 83,2% der invasiv beatmeten Patienten (n = 316). Bei assistiert-beatmeten Patienten konnte ein klarer Trend zu einem höheren HI (204 ± 70 mmHg) im Vergleich zu PCV (179 ± 74 mmHg) und VCV (175 ± 75 mmHg; p = 0,0551) festgestellt werden. Die multivariate logistische Regressionsanalyse identifizierte das Verhältnis zwischen dem Atemzugvolumen und dem Inspirationsdruck [“odds ratio“ (OR) = 0,94; 95%-Konfidenzintervall (95%-KI) 0,89–0,99], die renale Dysfunktion (OR = 2,15; 95%-KI 1,01–4,55) und den „Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II Score“ (OR = 1,09; 95%-KI 1,03–1,15), aber nicht den HI (univariate Analyse OR = 0,998, 95%-KI 0,995–1,001) als unabhängige Risikofaktoren für den Tod der Patienten.

Schlussfolgerungen

Diese repräsentative Beobachtungsstudie zeigte, dass die schwere Sepsis oder der septische Schock häufig mit einer Lungenschädigung einhergehen. Unterschiedliche Beatmungsformen beeinflussen hierbei nicht die Sterblichkeit der Patienten. Das Verhältnis von Atemzugvolumen zu Inspirationsdruck, aber nicht der HI war unabhängig mit der Sterblichkeit assoziiert.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference (1992) Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med 20:864–874

Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL et al (1994) The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 149:818–824

Bersten AD, Edibam C, Hunt T et al (2002) Incidence and mortality of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome in three Australian States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:443–448

Brander L, Slutsky AS (2006) Assisted spontaneous breathing during early acute lung injury. Crit Care 10:102

Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F et al (2008) Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 358:125–139

Deans KJ, Minneci PC, Cui X et al (2005) Mechanical ventilation in ARDS: one size does not fit all. Crit Care Med 33:1141–1143

Doyle RL, Szaflarski N, Modin GW et al (1995) Identification of patients with acute lung injury. Predictors of mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152:1818–1824

Elke G, Schädler D, Engel C et al (2008) Current practice in nutritional support and its association with mortality in septic patients–results from a national, prospective, multicenter study. Crit Care Med 36:1762–1767

Engel C, Brunkhorst FM, Bone HG et al (2007) Epidemiology of sepsis in Germany: results from a national prospective multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 33:606–618

Esteban A, Alia I, Gordo F et al (2000) Prospective randomized trial comparing pressure-controlled ventilation and volume-controlled ventilation in ARDS. For the Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Chest 117:1690–1696

Esteban A, Anzueto A, Alia I et al (2000) How is mechanical ventilation employed in the intensive care unit? An international utilization review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161:1450–1458

Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F et al (2002) Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA 287:345–355

Esteban A, Ferguson ND, Meade MO et al (2008) Evolution of mechanical ventilation in response to clinical research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177:170–177

Estenssoro E, Dubin A, Laffaire E et al (2002) Incidence, clinical course, and outcome in 217 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 30:2450–2456

Ferring M, Vincent JL (1997) Is outcome from ARDS related to the severity of respiratory failure? Eur Respir J 10:1297–1300

Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD et al (2012) Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 307:2526–2533

Gattinoni L, Pesenti A, Bombino M et al (1988) Relationships between lung computed tomographic density, gas exchange, and PEEP in acute respiratory failure. Anesthesiology 69:824–832

Henzler D, Pelosi P, Dembinski R et al (2005) Respiratory compliance but not gas exchange correlates with changes in lung aeration after a recruitment maneuver: an experimental study in pigs with saline lavage lung injury. Crit Care 9:R471–482

Karason S, Antonsen K, Aneman A (2002) Ventilator treatment in the Nordic countries. A multicenter survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 46:1053–1061

Karbing DS, Kjaergaard S, Smith BW et al (2007) Variation in the PaO2/FiO2 ratio with FiO2: mathematical and experimental description, and clinical relevance. Crit Care 11:R118

Laterre PF, Abraham E, Janes JM et al (2007) ADDRESS (ADministration of DRotrecogin alfa [activated] in Early stage Severe Sepsis) long-term follow-up: one-year safety and efficacy evaluation. Crit Care Med 35:1457–1463

Luhr OR, Karlsson M, Thorsteinsson A et al (2000) The impact of respiratory variables on mortality in non-ARDS and ARDS patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 26:508–517

Lumb A (2005) Nunn’s applied respiratory physiology, 4th edn. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, p 274

Marini JJ (1990) Lung mechanics in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Recent conceptual advances and implications for management. Clin Chest Med 11:673–690

Meade MO, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH et al (2008) Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299:637–645

Monchi M, Bellenfant F, Cariou A et al (1998) Early predictive factors of survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. A multivariate analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158:1076–1081

Montgomery AB, Stager MA, Carrico CJ et al (1985) Causes of mortality in patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 132:485–489

Nuckton TJ, Alonso JA, Kallet RH et al (2002) Pulmonary dead-space fraction as a risk factor for death in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 346:1281–1286

Oppert M, Engel C, Brunkhorst FM et al (2008) Acute renal failure in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock–a significant independent risk factor for mortality: results from the German Prevalence Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23:904–909

Papazian L, Forel JM, Gacouin A et al (2010) Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 363:1107–1116

Putensen C, Mutz NJ, Putensen-Himmer G et al (1999) Spontaneous breathing during ventilatory support improves ventilation-perfusion distributions in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:1241–1248

Putensen C, Zech S, Wrigge H et al (2001) Long-term effects of spontaneous breathing during ventilatory support in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164:43–49

Rappaport SH, Shpiner R, Yoshihara G et al (1994) Randomized, prospective trial of pressure-limited versus volume-controlled ventilation in severe respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 22:22–32

Rocco TR Jr, Reinert SE, Cioffi W et al (2001) A 9-year, single-institution, retrospective review of death rate and prognostic factors in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Surg 233:414–422

Seeley E, Mcauley DF, Eisner M et al (2008) Predictors of mortality in acute lung injury during the era of lung protective ventilation. Thorax 63:994–998

Slutsky AS (1994) Consensus conference on mechanical ventilation. January 28–30, 1993 at Northbrook, Illinois, USA. Part 2. Intensive Care Med 20:150–162

Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D et al (2008) Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med 358:111–124

Taccone P, Pesenti A, Latini R et al (2009) Prone positioning in patients with moderate and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302:1977–1984

Takeda S, Ishizaka A, Fujino Y et al (2005) Time to change diagnostic criteria of ARDS: towards the disease entity-based subgrouping. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 18:115–119

The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network (2000) Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342:1301–1308

Trachsel D, McCrindle BW, Nakagawa S et al (2005) Oxygenation index predicts outcome in children with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172:206–211

Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Ranieri VM (2003) Epidemiology and outcome of acute respiratory failure in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med 31:296–299

Ware LB (2005) Prognostic determinants of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults: impact on clinical trial design. Crit Care Med 33:217–222

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Berlin, Germany (BMBF, Grant No. 01 KI 0106) and an unrestricted grant from Lilly Germany, Bad Homburg, Germany. Neither party was actively involved in any phase of the study (design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review and decision to submit the manuscript for publication).

The authors thank all the ICU physicians throughout Germany who participated and devoted their time to the study.

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

D.S. participated in the design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. G.E. participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. C.E. and H.B. performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. I.F. helped to draft and revise the manuscript. R.K., M.Q. and J.S. helped in the analysis and interpretation of the data. R.R. helped in the analysis and interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript. F.M.B. and K.R. participated in the design of the study and helped in the analysis and interpretation of the data. M.L. helped in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. N.W. participated in the design, analysis and interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schädler, D., Elke, G., Engel, C. et al. Ventilatory strategies in septic patients. Anaesthesist 62, 27–33 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00101-012-2121-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00101-012-2121-2