Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of severe vision loss in adults over the age of 65 years. The advent of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) intravitreal injections has revolutionized the management of exudative AMD. However, multiple case series of sustained elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) after intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents have been reported. Sustained elevated IOP has been reported with all anti-VEGF agents being used in ophthalmology and even in patients without any prior history of glaucoma. No clear correlations to injection frequency or patient characteristics have emerged from the multiple reports so far, but it appears that patients with pre-existing glaucoma or ocular hypertension and those receiving a greater number of injections with shorter injection intervals may be at a higher risk for developing ocular hypertension related to anti-VEGF agents. Until future studies elucidate the pathophysiology of sustained IOP following anti-VEGF injections, it is prudent to recognize the possibility of elevations in IOP in association with anti-VEGF therapy. Treating physicians should look for subtle optic nerve head changes and IOP measurements suspicious for glaucoma and have a low threshold for treating elevated IOP if the patient is likely to require multiple intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. Ocular hypertension following anti-VEGF injections appears to be amenable to anti-glaucoma treatment and every effort should be made to preserve the peripheral vision in these patients where central vision is already threatened by exudative AMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Regillo CD, editor. 2007–2008 Basic and clinical science course section 12: retina and vitreous. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2007.

Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Munoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):564–72.

Guyer DR, Fine SL, Maguire MG, et al. Subfoveal choroidal neovascular membranes in age-related macular degeneration. Visual prognosis in eyes with relatively good initial visual acuity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104(5):702–5.

Ferris FL, Davis MD, Clemons TE, et al. A simplified severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(11):1570–4.

Ramulu PY, Do DV, Corcoran KJ, et al. Use of retinal procedures in Medicare beneficiaries from 1997 to 2007. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(10):1335–40.

Day S, Acquah K, Lee PP, et al. Medicare costs for neovascular age-related macular degeneration, 1994–2007. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(6):1014–20.

Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(14):1432–44.

Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(14):1419–31.

Argon laser photocoagulation for senile macular degeneration. Results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(6):912–8.

Chakravarthy U, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET Jr, et al. Year 2 efficacy results of 2 randomized controlled clinical trials of pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(9):1508.e1-25.

D’Amico DJ, Masonson HN, Patel M, et al. Pegaptanib sodium for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year safety results of the two prospective, multicenter, controlled clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(6):992–1001.

Moshfeghi AA, Puliafito CA. Pegaptanib sodium for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14(5):671–82.

Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1897–908.

Davis J, Olsen TW, Stewart M, et al. How the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trial results will impact clinical care. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(4):509–14.

Ohr M, Kaiser PK. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(4):585–91.

Kim JE, Mantravadi AV, Hur EY, et al. Short-term intraocular pressure changes immediately after intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(6):930–4.

Adelman RA, Zheng Q, Mayer HR. Persistent ocular hypertension following intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections. J Ocular Pharmacol Ther. 2010;26(1):105–10.

Bakri SJ, McCannel CA, Edwards AO, et al. Persistent ocular hypertension following intravitreal ranibizumab. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246(7):955–8.

Choi DY, Ortube MC, McCannel CA, et al. Sustained elevated intraocular pressures after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab, ranibizumab, and pegaptanib. Retina. 2011;31(6):1028–35.

Good TJ, Kimura AE, Mandava N, et al. Sustained elevation of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(8):1111–4.

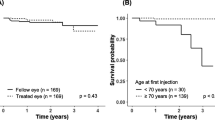

Hoang QV, Mendonca LS. Della Torre KE, et al. Effect on intraocular pressure in patients receiving unilateral intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):321–6.

Tseng JJ, Vance SK, Della Torre KE, et al. Sustained increased intraocular pressure related to intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(4):241–7.

Kahn HA, Leibowitz HM, Ganley JP, et al. The Framingham Eye Study. I. Outline and major prevalence findings. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(1):17–32.

Colton T, Ederer F. The distribution of intraocular pressures in the general population. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;25(3):123–9.

Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The ocular hypertension treatment study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):714–20. (discussion 829–30).

Friedman DS, Wolfs RC, O’Colmain BJ, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):532–8.

Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET Jr, et al. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2805–16.

Bakri SJ, Moshfeghi DM, Rundle A, et al. IOP in eyes treated with monthly ranibizumab: a post hoc analysis of data from the MARINA and ANCHOR Trials. AAO Annual Meeting, 17 Oct 2010, Chicago.

Falkenstein IA, Cheng L, Freeman WR. Changes of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin). Retina. 2007;27(8):1044–7.

Wilkinson CP, Brinton DA. Retinal detachment principles and practice. 3rd edn. Ophthalmology Monograph. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Bushley DM, Parmley VC, Paglen P. Visual field defect associated with laser in situ keratomileusis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(5):668–71.

Kahook MY, Ammar DA. In vitro effects of antivascular endothelial growth factors on cultured human trabecular meshwork cells. J Glaucoma. 2010;19(7):437–41.

Kernt M, Welge-Lussen U, Yu A, et al. Bevacizumab is not toxic to human anterior- and posterior-segment cultured cells. Ophthalmologe. 2007;104(11):965–71.

Kahook MY, Liu L, Ruzycki P, et al. High-molecular-weight aggregates in repackaged bevacizumab. Retina. 2010;30(6):887–92.

Liu L, Ammar DA, Ross LA, et al. Silicone oil microdroplets and protein aggregates in repackaged bevacizumab and ranibizumab: effects of long-term storage and product mishandling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(2):1023–34.

Freund KB, Laud K, Eandi CM, et al. Silicone oil droplets following intravitreal injection. Retina. 2006;26(6):701–3.

Bakri SJ, Ekdawi NS. Intravitreal silicone oil droplets after intravitreal drug injections. Retina. 2008;28(7):996–1001.

Scott IU, Oden NL, VanVeldhuisen PC, et al. SCORE Study Report 7: incidence of intravitreal silicone oil droplets associated with staked-on vs luer cone syringe design. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5):725–32.

Perkumas KM, Stamer WD. Protein markers and differentiation in culture for Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2012;96(1):82–7.

Paylakhi SH, Yazdani S, April C, et al. Non-housekeeping genes expressed in human trabecular meshwork cell cultures. Mol Vis. 2012;18:241–54.

Shin JW, Huggenberger R, Detmar M. Transcriptional profiling of VEGF-A and VEGF-C target genes in lymphatic endothelium reveals endothelial-specific molecule-1 as a novel mediator of lymphangiogenesis. Blood. 2008;112(6):2318–26.

Zampell JC, Avraham T, Yoder N, et al. Lymphatic function is regulated by a coordinated expression of lymphangiogenic and anti-lymphangiogenic cytokines. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302(2):C392–404.

Singh D. Conjunctival lymphatic system. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29(4):632–3.

Aref AA. Management of immediate and sustained intraocular pressure rise associated with intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor injection therapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(2):105–10.

CATT Research Group, Martin DF, Maguire MG, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1388–98.

Fung AE, Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. An optical coherence tomography-guided, variable dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(4):566–83.

Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, et al. A variable-dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: year 2 of the PrONTO Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(1):43–58.e1.

Holz FG, Amoaku W, Donate J, et al. Safety and efficacy of a flexible dosing regimen of ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the SUSTAIN study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(4):663–71.

Theoulakis PE, Lepidas J, Petropoulos IK, et al. Effect of brimonidine/timolol fixed combination on preventing the short-term intraocular pressure increase after intravitreal injection of ranibizumab. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2010;227(4):280–4.

Frenkel MP, Haji SA, Frenkel RE. Effect of prophylactic intraocular pressure-lowering medication on intraocular pressure spikes after intravitreal injections. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(12):1523–7.

Schumer RA, Camras CB, Mandahl AK. Latanoprost and cystoid macular edema: is there a causal relation? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11(2):94–100.

Hollands H, Wong J, Bruen R, et al. Short-term intraocular pressure changes after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(6):807–11.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the preparation of this article was provided in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY, USA. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, R.S.J., Kim, J.E. Ocular Hypertension Following Intravitreal Anti-vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Agents. Drugs Aging 29, 949–956 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-012-0031-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-012-0031-2