Abstract

Introduction

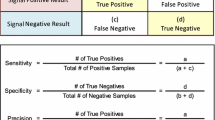

The objective of post-marketing surveillance of medicines is to rapidly detect adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Early ADR detection will enable policy makers and health professionals to recognise adverse events that may not have been identified in pre-marketing clinical trials. Multiple methods exist for ADR signal detection. Traditional quantitative methods employed in spontaneous reports data have include reporting odds ratio (ROR), proportional reporting ratio (PRR) and Bayesian techniques. With the development of administrative health claims databases, additional methods such as sequence symmetry analysis (SSA) may be able to be employed routinely to confirm ADR signals.

Objective and Method

We tested the time to signal detection of quantitative ADR signalling methods in a health claims database (SSA) and in a spontaneous reporting database (ROR, PRR, Bayesian confidence propagation neural network) for rofecoxib-induced myocardial infarction and rosiglitazone-induced heart failure.

Results

This study demonstrated that all four signalling methods detected safety signals within 1–3 years of market entry or subsidisation of the medicines, and for both cases the signals were detected before post-marketing clinical trial results. By contrast, the trial results and subsequent warning or withdrawal were published 5–7 years after first marketing of these medicines.

Conclusion

This case study highlights that a post-marketing quantitative method utilising administrative claims data can be a complementary tool to traditional quantitative methods employed in spontaneous reports that may help to verify safety signals detected in spontaneous reporting data.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Paludetto M-N, Olivier-Abbal P, Montastruc J-L. Is spontaneous reporting always the most important information supporting drug withdrawals for pharmacovigilance reasons in France? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(12):1289–94.

Clarke A, Deeks JJ, Shakir SAW. An assessment of the publicly disseminated evidence of safety used in decisions to withdraw medicinal products from the UK and US markets. Drug Saf. 2006;29(2):175–81.

Wood AJJ. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and clopidogrel—a need for new approaches to drug safety. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(24):1824–6.

Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ, Himmelstein DU, Wolfe SM, Bor DH. Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2215–20.

Roughead E, Semple S. Medication safety in acute care in Australia: where are we now? Part 1: a review of the extent and causes of medication problems 2002–2008. Aust N Z Health Policy. 2009;6(1):18.

Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1200–5.

Wu C, Bell CM, Wodchis WP. Incidence and economic burden of adverse drug reactions among elderly patients in Ontario emergency departments: a retrospective study. Drug Saf. 2012;35(9):769–81.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Vioxx (rofecoxib). Medicine recall. 2004. http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/recalls-medicine-vioxx-041001.htm. Accessed 10 Jul 2013.

Graham DJ, Campen D, Hui R, Spence M, Cheetham C, Levy G, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death in patients treated with cyclo-oxygenase 2 selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: nested case-control study. Lancet. 2005;365(9458):475–81.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. FDA news release: FDA adds boxed warning for heart-related risks to anti-diabetes drug Avandia. 2007. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2007/ucm109026.htm. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency recommends suspension of Avandia, Avandamet and Avaglim: anti-diabetes medication to be taken off the market. 2010. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2010/09/WC500096996.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2012.

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration. Product information, Avandia (rosiglitazone). 2013. https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2010-PI-06879-3. Accessed 2 May 2013.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA. FDA approved drug products. AVANDIA (rosiglitazone maleate) tablets. 2007. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/021071s031lbl.pdf. Accessed 2 May 2013.

Evans SJW, Waller PC, Davis S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2001;10(6):483–6.

Egberts ACG, Meyboom RHB, Van Puijenbroek EP. Use of measures of disproportionality in pharmacovigilance: three Dutch examples. Drug Saf. 2002;25(6):453–8.

Bate A, Lindquist M, Edwards IR, Olsson S, Orre R, Lansner A, et al. A Bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54(4):315–21.

Hallas J. Evidence of depression provoked by cardiovascular medication: a prescription sequence symmetry analysis. Epidemiology. 1996;7(5):478–84.

Caughey GE, Roughead EE, Pratt N, Killer G, Gilbert AL. Stroke risk and NSAIDs: an Australian population-based study. Med J Aust. 2011;195(9):525–9.

Corrao G, Botteri E, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Carobbio A, Falcone C, et al. Generating signals of drug-adverse effects from prescription databases and application to the risk of arrhythmia associated with antibacterials. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(1):31–40.

Bytzer P, Hallas J. Drug-induced symptoms of functional dyspepsia and nausea. A symmetry analysis of one million prescriptions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(11):1479–84.

Hallas J, Bytzer P. Screening for drug related dyspepsia: An analysis of prescription symmetry. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10(1):27–32.

Hersom K, Neary MP, Levaux HP, Klaskala W, Strauss JS. Isotretinoin and antidepressant pharmacotherapy: a prescription sequence symmetry analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(3):424–32.

Lindberg G, Hallas J. Cholesterol-lowering drugs and antidepressants—a study of prescription symmetry. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1998;7(6):399–402.

Silwer L, Petzold M, Hallas J, Lundborg CS. Statins and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—an analysis of prescription symmetry. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(7):510–1.

Tsiropoulos I, Andersen M, Hallas J. Adverse events with use of antiepileptic drugs: a prescription and event symmetry analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(6):483–91.

Vegter S, De Jong-Van Den Berg LTW. Misdiagnosis and mistreatment of a common side-effect—angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(2):200–3.

Wahab IA, Pratt NL, Wiese MD, Kalisch LM, Roughead EE. The validity of sequence symmetry analysis (SSA) for adverse drug reaction signal detection. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(5):496–502.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Database of Adverse Event Notifications. 2012. http://www.tga.gov.au/daen/daen-report.aspx. Accessed 26 Nov 2012.

MedDRA MSSO (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, Maintenance and Support Services Organization). 2012. http://www.meddra.org/about-meddra/organisation/msso. Accessed 7 Apr 2013.

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities-MedDRA. 2013. http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/daen-meddra.htm. Accessed 7 Apr 2013.

Gould AL. Practical pharmacovigilance analysis strategies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12(7):559–74.

Hauben M, Madigan D, Gerrits CM, Walsh L, Van Puijenbroek EP. The role of data mining in pharmacovigilance. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4(5):929–48.

Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Treatment population statistics. Quarterly report—March 2011. 2011. http://www.dva.gov.au/aboutDVA/Statistics/Documents/TpopMar2011.pdf. Accessed 27 Jul 2011.

World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Code Classification/Defined Daily Dose Index. 2011. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed 28 Feb 2011.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. Schedule of pharmaceutical benefits. PBS for health professional. 2011. http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/healthpro/explanatory-notes/section1/Section_1_2_Explanatory_Notes. Accessed 28 Feb 2011.

National Centre for Classification in Health. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth Revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM). Sydney: National Centre for Classification in Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney; 2004.

Australian Government. Department of Health and Ageing. Therapeutic Goods Administration. 2012. http://www.tga.gov.au/. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

United States of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Drugs@FDA. FDA approved drug products. 2012. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Search_Drug_Name. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian adverse drug reactions bulletin. 2012. http://www.tga.gov.au/hp/aadrb.htm. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

Australian Government. Medicare Australia. Medicare Australia statistics. 2013. https://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/statistics/pbs_item.shtml. Accessed 3 April 2013.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. Australian statistics on medicines. 2012. http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/asm/asm-2009. Accessed 16 Apr 2013.

New drugs. Rofecoxib. Aust Prescr. 2000;23:137–9.

Langman MJ, et al. Adverse upper gastrointestinal effects of rofecoxib compared with nsaids. JAMA. 1999;282(20):1929–33.

Feldman M, McMahon AT. Do cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors provide benefits similar to those of traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, with less gastrointestinal toxicity? Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(2):134–43.

United States Food and Drug Administration. Drug approval package. Voxx (rofecoxib) tablets. Company: Merck Research Laboratories. Application no.: 021042 & 021052. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/021042_52_Vioxx.cfm. Accessed 17 May 2013.

Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(21):1520–8.

Cheng JC, Siegel LB, Katari B, Traynoff SA, Ro JO. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin: a comparison of the antiplatelet effects. Am J Ther. 1997;4(2–3):62–5.

United States Food and Drug Administration. Sequence of events with VIOXX, since opening of IND. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/05/briefing/2005-4090B1_04_E-FDA-TAB-C.htm. Accessed 17 May 2013.

United States Food and Drug Administration. NDA 21-042: VIOXX tablets. NDA 21-052: VIOXX oral suspension (rofecoxib). http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3677b2_01_merck.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2013.

United States of America, Food and Drug Administration, Centre for Drug Evaluation and Research. Medical review (rofecoxib). http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2002/21-042S007_Vioxx_medr_P1.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2013.

Konstam MA, Weir MR, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Sperling RS, Barr E, et al. Cardiovascular thrombotic events in controlled, clinical trials of rofecoxib. Circulation. 2001;104(19):2280–8.

NDA 21-042/s007. Vioxx (rofecoxib). Cardiovascular data in Alzheimer’s studies. http://dida.library.ucsf.edu/pdf/oxx01l10. Accessed 16 May 2013.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Vioxx (rofecoxib). 2002. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm154520.htm. Accessed 26 Nov 2012.

Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. 2003 Oct;22(5). http://www.tga.gov.au/pdf/aadrb-0310.pdf. Accessed 26 Nov 2012.

Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1092–102.

United States Food and Drug Administration, Drugs@FDA, Label and Approval History. Avandia (rosiglitazone maleate). Label. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/1999/21071lbl.pdf. Accessed 18 May 2013.

Nesto RW, Bell D, Bonow RO, Fonseca V, Grundy SM, Horton ES, et al. Thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. Circulation. 2003;108(23):2941–8.

United States Department of Health and Human Serviced, Food and Drug Administration. Drug approval package. Avandia (rosiglitazone maleate) tablets. Centre for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 021071. Medical review. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/21071_Avandia_medr.pdf. Accessed 2 May 2013.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA, FDA approved drug products. Prescribing information Avandia. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/1999/21071lbl.pdf. Accessed 26 Jun 2013.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/. Accessed 21 Dec 2012.

Australian Government, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Veterans’ Affairs Pharmaceutical Advisory Centre (VAPAC). http://www.dva.gov.au/service_providers/pharmacy/Pages/vapac.aspx. Accessed 2 May 2013.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Safety. Avandia (rosiglitazone) April 2002. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm154468.htm. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Safety: summary-FDA April 2002, ACTOS [pioglitazone HCl]; AVANDIA [rosiglitazone maleate]. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/UCM170872.pdf. Accessed 7 Dec 2012.

Felix B, editor. Australian medicines handbook 2002. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd; 2002.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods and Administration. Australia adverse drug reactions bulletin, vol. 22, no. 2. http://www.tga.gov.au/hp/aadrb-0304.htm. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

GlaxoSmithKline. Press release: Avandia receives PBS listing. http://www.gsk.com.au/resources.ashx/MediaCentreChildDataAssociatedDownloads/31/File/C974E854090FD80DD9CF0E0F94D0C943/Avandia_Press_release_20031124.pdf. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

National Prescribing Service Limited. Early use of insulin and oral antidiabetic agents. http://www.nps.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/35231/PPR40_insulin_and_oral_antidiabetic_drugs_0308.pdf. Accessed 2 Dec 2012.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Information for healthcare professionals rosiglitazone maleate (marketed as Avandia, Avandamet, and Avandaryl). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm143406.htm. Accessed 7 Dec 2012.

Effect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1096–105.

Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJA, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1279–89.

Glaxo Smith Kline. Study no 049653/211 a 52 week double blind study of the effect of rosiglitazone on cardiovascular structure and function in subjects with type 2 diabetes and congestive heart failure. http://ctr.gsk.co.uk/Summary/Rosiglitazone/IV_49653_211.pdf. Accessed 2 May 2013.

Singh S, Loke YK, Furberg CD. Thiazolidinediones and heart failure: a teleo-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2007;29:2007.

Therapeutic Good Administration eBusiness Services. Product and consumer medicine information. Product information Avandia (rosiglitazone). https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2010-PI-06879-3. Accessed 2 May 2013.

Reicin AS, Shapiro D, Sperling RS, Barr E, Yu Q. Comparison of cardiovascular thrombotic events in patients with osteoarthritis treated with rofecoxib versus nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen, diclofenac, and nabumetone). Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(2):204–9.

Layton D, Riley J, Wilton LV, Shakir SAW. Safety profile of rofecoxib as used in general practice in England: results of a prescription-event monitoring study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(2):166–74.

Mamdani MRPJDN, et al. Effect of selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors and naproxen on short-term risk of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(4):481–6.

Ray WA, Stein CM, Daugherty JR, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Griffin MR. COX-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of serious coronary heart disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1071–3.

Thal LJ, Ferris SH, Kirby L, Block GA, Lines CR, Yuen E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, study of rofecoxib in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(6):1204–15.

Reines SA, Block GA, Morris JC, Liu G, Nessly ML, Lines CR, et al. No effect on Alzheimer’s disease in a 1-year, randomized, blinded, controlled study. Neurology. 2004;62(1):66–71.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Drugs at FDA: FDA approved drug products. Vioxx (rofecoxib). NDA 21-042 (capsules) and NDA 21-052 (oral solution). http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/021042_52_vioxx_medr_P1.pdf. Accessed 10 Jul 2013.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs and Therapeutic Goods Administration for providing the data used in this study. No sources of funding were used in the preparation of this manuscript and the research. The authors, Izyan A. Wahab, Nicole L. Pratt, Lisa E. Kalisch and Elizabeth E. Roughead, have no conflicts of interest relevant to this study. The MedDRA® trademark is owned by the International Federation of Pharmaceuticals Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) on behalf of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

A.Wahab, I., Pratt, N.L., Kalisch, L.M. et al. Comparing Time to Adverse Drug Reaction Signals in a Spontaneous Reporting Database and a Claims Database: A Case Study of Rofecoxib-Induced Myocardial Infarction and Rosiglitazone-Induced Heart Failure Signals in Australia. Drug Saf 37, 53–64 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0124-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0124-9