Abstract

Evidence indicates that there is a substantial inflammatory component associated with COPD and that this inflammation is increased during the acute exacerbation. The role of inhaled steroids in COPD has been established through a variety of studies. Inhaled steroids are most effective when given in conjunction with long-acting beta agonists. In those circumstances, patients have an improvement in quality of life, lessening of dyspnea, reduced use of rescue medications, and, in some studies, fewer exacerbations. The side effects associated with inhaled steroid use include an increase in the incidence of pneumonia and cataracts. National recommendations are for the use of inhaled steroids only in conjunction with a long-acting beta agonist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) have been studied as a treatment option either alone or in combination with beta agonists in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for a number of years. The nature and method of effectiveness has been the subject of considerable study. Various organizations have promulgated guidelines for the indications for ICS in the management of COPD. This article will outline the rationale, evidence and recommendations for the use of ICS in the management of this disease.

COPD is a heterogeneous group of structural and functional lung disorders most commonly associated with long-term cigarette smoking. The disease is characterized by airway destruction, inflammation, and air flow limitation in various combinations. COPD affects both the airways and the alveoli. It is characterized by both cellular and other markers of inflammation. It is thought that the degree of inflammation increases as the disease severity progresses. Prior studies have shown that progression of COPD through stages of severity is associated with an increase in inflammatory exudates and airway wall tissue volume [1]. It is also associated with an increase in polymorphonuclear neutrophils, macrophages, CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, B cells, and lymphoid aggregates. The effects of cigarette smoking, even prior to the development of clinical COPD are associated with an increase in both macrophages and neutrophils [2]. Peribronchiolar inflammation is thought to be associated with the development of centrilobular emphysema. Elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and leukocytes are associated with an increased risk of COPD exacerbations [3•].

Studies have shown that treatment with ICS for a period of a month is associated with a decrease in mucosal mast cells [4]. Even during a shorter treatment period, the use of inhaled fluticasone has been found to be associated with reduced levels of tumor necrosis factor, interferon, L-selectin, and intercellular effusion molecule [5]. Inhaled budesonide has been found to decrease eosinophil counts, interleukin-8, and eosinophilic cationic protein [6]. In other studies the use of fluticasone with or without salmeterol was associated with changes in surfactant protein D but not with C-reactive protein or IL-6 levels [7]. A combination of inhaled fluticasone and salmeterol has been found to reduce the acidophilic airway inflammation over the course of two months. This change in the acidophilia was not associated with the degree of bronchodilator reversibility [8]. The interpretation of these studies is that there is a degree of inflammation associated with COPD that increases with the severity of COPD and with the risk of exacerbations. Treatment with ICS is variably associated with a decrease in these inflammatory markers.

Clinical Studies with Stable Patients

A number of studies have investigated the use of ICS in patients with stable COPD. The ISOLDE trial evaluated non-asthmatic patients with moderate to severe COPD, defined as patients with a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) <50 % of predicted normal. These patients were randomized to inhaled fluticasone or placebo and treated for a period of three years with the primary end point being improvement in the rate of decline of pulmonary function [9]. While the study did not reach its primary end point, analysis of secondary end points found that patients on ICS had fewer exacerbations and a slower decline in health status. In another study, treatment for a year with mometasone found that patients treated with ICS had a reduction in COPD symptom scores and an improvement in overall health status [10]. In contradistinction to the ISOLDE trial, treatment with ICS either once daily or twice daily was associated with improvement in pulmonary function. Similarly a shorter-term trial over the course of 12 weeks found that treatment with ICS was associated with an improvement in COPD symptom scores and pulmonary function although an effect on inflammatory cytokines was not seen [11]. Other studies have found that the effectiveness of ICS was related to baseline spirometric measures of severity. Inhaled fluticasone was associated with a reduction in COPD exacerbations in patients with moderate to severe disease but not in those with mild disease [12]. In a study of mortality, a review of an administrative database evaluated the effects of ICS on mortality among patients 3–12 months after hospital discharge for COPD. The use of ICS was associated with a 25 % reduction in mortality [13]. This reduction was most marked in the reduced number of cardiovascular deaths compared with patients receiving bronchodilators without associated steroid use.

Meta-Analysis of Monotherapy in Stable Patients

Various authors have conducted meta-analyses of studies evaluating the effect of ICS in stable patients. The ISEEC study was an evaluation of seven long-term, randomized controlled trials of ICS versus placebo of 12 months or more in duration. This study was limited to patients with moderate to severe COPD [14]. The authors found that over the course of the first six months after randomization the use of ICS was associated with a significant beneficial effect on FEV1. The effects were most dramatic in former smokers compared with current smokers and women in this study had a better response to ICS compared with males. A Cochrane review evaluated 55 primary studies that compared any ICS with placebo among patients with COPD [15••]. Similar to the results of the ISOLDE trial, this meta analysis did not find a consistent reduction in the rate of decline of pulmonary function over more than six months. There was no overall change in mortality. The long-term use of ICS was associated with a reduction in exacerbations and an improvement in the rate of decline of quality of life. The response to ICS was not predicted by oral steroid response, bronchodilator reversibility, or bronchial hyper responsiveness.

Guidelines on the Use of Monotherapy

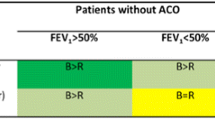

The results of these studies have been incorporated into various society or other guidelines. The Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) does not recommend long-term monotherapy with ICS. They also find that there is no rationale for determining whether ICS should be used on the basis of responsiveness to oral corticosteroids [16•]. A clinical practice guideline based on a collaboration of the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society similarly does not recommend monotherapy with ICS or other agents for patients with an FEV1 >50 % of predictive normal [17•].

Combination Treatment with Long-Acting Beta-Agonists

The cornerstone of treatment with ICS is in their combination with long-acting beta agonists. The TRISTAN trial was a large multi-national trial involving the use of the combination of salmeterol and fluticasone over the course of 12 months [18]. Combined therapy led to significantly greater improvement in pre-treatment pulmonary function compared with either placebo or monotherapy with either salbuterol or fluticasone. There was a significant improvement in overall health status and in daily symptoms. There was also a reduction in exacerbation rate compared with placebo but not compared with monotherapy with either salbuterol or fluticasone. A three-month comparison of long-term, long-acting beta agonists (LABA) with or without ICS found that pulmonary function and walking distance was greatest for patients treated with combination therapy [19]. A study of an administrative database of patients involved with a managed care program found that use of the combination of an ICS with a LABA compared with any other inhaled maintenance strategy was associated with fewer subsequent hospitalizations or ED visits over the coming year [20]. Addition of the combination of an ICS with a LABA to treatment with an anticholenergic inhaler has been associated with a decrease in exacerbations over a three-month time period [21]. Although ICS is generally associated with long-term treatment effects, several studies have found that addition of an ICS has been associated with an increase in the speed of effectiveness of bronchodilators. Over the course of 60 min addition of an ICS to formoterol was associated with more rapid improvement in pulmonary function [22]. Another study compared the combination of LABA and an ICS against placebo, LABA alone, or ICS alone over the course of three years with the primary end point of death from any cause. There was no significant difference in overall mortality. This study did find a decrease in the annual rate of exacerbations and an improvement in spirometry for all of the comparisons with a placebo [23]. Several studies have evaluated the effects of withdrawal of the ICS component of a combination ICS and LABA treatment. One study which allowed for a four-month running trial period on an ICS evaluated the effectiveness of withdrawal of that ICS. This was associated with an increase in exacerbations and hospital admissions [24]. A similar study monitored the effects of one year withdrawal of an ICS after a three-month run-in period of combination treatment. This was associated with an increase in exacerbation rates, a worsening of patient symptoms, and a decline in pulmonary function [25].

Meta-Analysis of Combination Therapy

A recent meta-analysis evaluated 14 studies which compared combination therapy with an ICS and a LABA compared with a LABA alone. These studies included nearly 12,000 patients [26]. Although there was significant heterogeneity among the studies, there was an improvement in health quality of life, dyspnea, pulmonary function, and use of rescue medication among patients with the combination therapy. There was no difference in the rate of hospitalizations or mortality.

Guidelines for Combination Therapy

Various groups and societies have generally recommended the use of combination therapy with an ICS and a LABA for patients with moderate to severe disease. The guidelines published by a collaboration of various pulmonary-related organizations has recommended the addition of a combination therapy for patients with stable COPD and a FEV1 <60 % of predicted normal [17•]. The GOLD recommendations are to add combination therapy to patients at high risk of exacerbations [16•].

Adverse Effects

Inhaled corticosteroids are associated with a variety of adverse effects. Minor effects include candidiasis, which can be seen with the use of an ICS in other conditions, such as asthma. There have been concerns about the progression of osteoporosis with the use of ICS among patients with COPD. Analysis of data from the TORCH study did not find an increase in osteoporosis with the use of ICS. A similar analysis using an administrative database did not find an association between combination therapy with an ICS and the incidence of non-vertebral fractures [27, 28]. Data from various studies have found an association between ICS use and community-acquired pneumonia [29]. The incidence of pneumonia in patients receiving an ICS, however, is small compared with the incidence of exacerbations [30•]. An analysis from the TORCH study also found an increase in the incidence of pneumonia for patients receiving an ICS compared with those receiving a LABA alone [31]. Finally, several studies have evaluated the incidence of either new-onset diabetes, change in HbA1C, or hyperglycemia in patients receiving an ICS [32, 33]. The long-term use of ICS has been shown to be related in a dose-dependent manner to the development of cataracts [34].

Conclusions

In summary, the use of ICS in combination with a long-acting beta agonist is recommended for patients with moderate to severe COPD or those that are high risk for exacerbations. Monotherapy with ICS is generally not recommended for patients with COPD, in contrast with patients with asthma. The use of these medications may be associated with adverse effects. Monitoring for these side effects is warranted during long-term use.

References

Papers of Importance, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Hogg JC, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(26):2645–53.

Jeffery PK. Structural and inflammatory changes in COPD: a comparison with asthma. Thorax. 1998;53(2):129–36.

• Thomsen MIT, Marott JL, et al. Inflammatory biomarkes and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2353–61. This study outlines the association of inflammation with acute exacerbations of COPD.

Gizycki MJ, et al. Effects of fluticasone propionate on inflammatory cells in COPD: an ultrastructural examination of endobronchial biopsy tissue. Thorax. 2002;57(9):799–803.

Man SF, et al. The effects of inhaled and oral corticosteroids on serum inflammatory biomarkers in COPD: an exploratory study. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2009;3(2):73–80.

Boorsma M, et al. Long-term effects of budesonide on inflammatory status in COPD. COPD. 2008;5(2):97–104.

Sin DD, et al. The effects of fluticasone with or without salmeterol on systemic biomarkers of inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1207–14.

Perng DW, et al. Inhaled fluticasone and salmeterol suppress eosinophilic airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: relations with lung function and bronchodilator reversibility. Lung. 2006;184(4):217–22.

Burge PS, et al. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of fluticasone propionate in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ISOLDE trial. BMJ. 2000;320(7245):1297–303.

Calverley PM, et al. One-year treatment with mometasone furoate in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2008;9:73.

John M, et al. Effects of inhaled HFA beclomethasone on pulmonary function and symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2005;99(11):1418–24.

Jones PW, et al. Disease severity and the effect of fluticasone propionate on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(1):68–73.

Macie C, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids and mortality in COPD. Chest. 2006;130(3):640–6.

Soriano JB, et al. A pooled analysis of FEV1 decline in COPD patients randomized to inhaled corticosteroids or placebo. Chest. 2007;131(3):682–9.

•• Yang IA, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7: CD002991. This meta-analysis reviewes 55 studies covering over 16000 patients. The main findings are that inhaled corticosteroids did not consistently effect the rate of decline in pulmonary function. It did decrease the incidence of exacerbation and slowed the rate of decline in quality of life.

• Vestbo J, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347–65. This is a recent review of the treatment of stable COPD including recommendations for the use of inhaled corticosteroids.

• Qaseem A, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):179–91. This is a collaborative review of the treatment of stable COPD with recommendations on a variety of medications, including inhaled corticosteroids.

Calverley P, et al. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9356):449–56.

Mansori F, et al. The effect of inhaled salmeterol, alone and in combination with fluticasone propionate, on management of COPD patients. Clin Respir J. 2010;4(4):241–7.

Dalal AA, et al. COPD-related healthcare utilization and costs after discharge from a hospitalization or emergency department visit on a regimen of fluticasone propionate-salmeterol combination versus other maintenance therapies. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(3):e55–65.

Mittmann N, et al. Cost effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol added to tiotropium bromide versus placebo added to tiotropium bromide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Australian, Canadian and Swedish healthcare perspectives. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(5):403–14.

Cazzola M, et al. Onset of action of formoterol/budesonide in single inhaler vs. formoterol in patients with COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2004;17(3):121–5.

Calverley PM, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–89.

van der Palen J, et al. Cost effectiveness of inhaled steroid withdrawal in outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2006;61(1):29–33.

Wouters EF, et al. Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD causes immediate and sustained disease deterioration: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2005;60(6):480–7.

Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

Ferguson GT, et al. Prevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the towards a revolution in COPD health study. Chest. 2009;136(6):1456–65.

Miller DP, et al. Long-term use of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol fixed-dose combination and incidence of nonvertebral fractures among patients with COPD in the UK General Practice Research Database. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38(4):19–27.

Almirall J, et al. Inhaled drugs as risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(5):1080–7.

• Calverley PM, et al. Reported pneumonia in patients with COPD: findings from the INSPIRE study. Chest. 2011;139(3):505–12. This study reviews the increase in reported incidence of pneumonia in patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids.

Crim C, et al. Pneumonia risk in COPD patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids alone or in combination: TORCH study results. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):641–7.

O’Byrne PM, et al. Risk of new onset diabetes mellitus in patients with asthma or COPD taking inhaled corticosteroids. Respir Med. 2012;106(11):1487–93.

Faul JL, et al. The effect of an inhaled corticosteroid on glucose control in type 2 diabetes. Clin Med Res. 2009;7(1–2):14–20.

Weatherall M, et al. Dose-response relationship of inhaled corticosteroids and cataracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respirology. 2009;14(7):983–90.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

C. Emerman is a consultant for, and has provided expert testimony for, various legal firms.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Emerman, C.L. Effectiveness of Inhaled Steroids in the Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep 1, 189–192 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40138-013-0022-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40138-013-0022-6