Abstract

Background

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an important pathogen not only in nosocomial infections, but also in community-associated infections. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impacts of methicillin resistance on mortality, length of hospitalization, and hospital costs via propensity score matching in S. aureus bacteremia.

Patients and methods

A propensity-matched case–control study was conducted in a tertiary hospital in Korea from 2003 to 2008.

Results

A total of 266 patients who had clinically significant S. aureus bloodstream infections were investigated. Fifty-three propensity-matched case–control pairs with MRSA bacteremia were likely to have stayed in the hospital longer before developing bacteremia (mean 25.0 vs. 6.1 days; P = 0.01). However, after developing bacteremia, the differences in the mean duration of hospital stay was not significant (mean 35.0 vs. 28.7 days; P = 0.33). Similar numbers of MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) patients died (P = 0.48). The mean total hospital costs after S. aureus bacteremia increased more for MRSA patients compared to MSSA patients. However, this difference was not statistically significant ($9,369.6 vs. $8,355.8; P = 0.62).

Conclusions

This study indicates that MRSA bacteremia is not associated with higher risks of mortality or hospital costs. It is, however, associated with a substantial increase in the length of hospital stay as compared to MSSA bacteremia. This information may help clinicians and policymakers derive methods to control the impacts of MRSA infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was first reported in England in 1961, and the current mortality rate associated with serious MRSA infection is estimated to be 20–25% [1]. According to a report by the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System in 2004, MRSA infection in intensive care units (ICUs) increased from 11% in 1998 to 60% in 2003 [2]. From July 2004 through December 2005, the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) system and the Emerging Infections Program (EIP) of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted surveillance for invasive MRSA infections. Most MRSA infections were healthcare-associated, but 13.7% were community-associated infections [3]. MRSA is an important pathogen not only for hospital infections, but also for community-associated infections. Furthermore, in the past, MRSA infections have been limited to patients with risk factors such as dialysis, diabetes, or usage of a ventilator or invasive medical devices. But recently, community-acquired MRSA infections have been reported in the absence of identified risk factors [4].

According to one study in Korea [5] which evaluated the nationwide nosocomial infection rate in 2004 and antimicrobial resistance in ICUs, S. aureus was the most frequently identified microorganism (23.2%). MRSA was also the most common pathogenic cause of bacteremia, pneumonia, and surgical site infection, with frequencies of 16.5, 90, and 21%, respectively. The study found that 93% of S. aureus isolates were resistant to methicillin, up from 79% in 1996. This rate was also higher than the 60% MRSA infection rate in US ICUs reported by the NNIS System from 2004. These findings show that MRSA infection has become a serious public health issue in Korea.

In a study conducted by Haley et al. [6], the prevention of nosocomial infections resulted in cost savings of about 95%. Moreover, another study [7] showed that the attributable costs spent by hospitals to prevent MRSA infections were $35,367, affirming the hypothesis that MRSA infection control is important not only for patient health but also economically.

The development of antimicrobial resistance in S. aureus and the prognosis of infected patients has been debated in the study of MRSA infection. Specifically, its effects on the length of hospitalization and hospital cost are controversial.

Careful adjustment for confounding factors is important when comparing outcomes between patients with MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) bacteremia [8]. The propensity score is a powerful device for constructing matched pairs or matched sets that balance numerous observed covariates, and is sufficient to remove bias regardless of the sample size [9]. In the present study, a propensity score matching method was used to evaluate the impact of methicillin resistance on mortality, length of hospitalization, and hospital costs in patients with S. aureus bacteremia.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This study was conducted at Kyung Hee University Medical Center, a 1,200-bed, tertiary care hospital in Korea. All patients with blood cultures positive for S. aureus were identified from a retrospective review of medical records from between 1st January 2003, and 31st December 2008.

Two situations of S. aureus bacteremia were considered to be clinically significant. One circumstance was two or more positive blood cultures for S. aureus within 24 h. The second was if the patient had clinical signs and symptoms of infection but no concurrent infection with another organism that would explain the displayed signs and symptoms. If a patient had any recurrent episodes of S. aureus bacteremia during the study period, only the first episode was considered. Also, if the antibiotic susceptibility changed in recurrent episodes, only the first susceptibility was included.

Patients with healthcare-acquired S. aureus infection diagnosed >48 h after hospital admission or those who had resided in a long-term care facility in the 12 months preceding the culture date were included in this study. Those patients with a community-acquired infection that had been diagnosed within 48 h of hospital admission were also included. The source of bacteremia was classified according to clinician assessment as primary or secondary at the time of S. aureus bacteremia based on the evaluation of medical records [10]. A bacteremia was considered to be central venous catheter-associated if the same organisms were observed in at least one percutaneous blood culture, as well as in a culture of the catheter tip or from two blood samples drawn from a catheter hub and a peripheral vein, with no other apparent infection source [11]. Empirical therapy was defined as the first antibiotic regimen following the onset of bacteremia. Concordant treatment was defined as treatment with an antimicrobial agent that was susceptible according to culture results. The route of administration and the timing relative to the first positive blood culture were also considered.

Patient demographics (age and sex), comorbidities (underlying malignancy, diabetes, chronic lung disease, liver disease, or renal disease), previous antibiotic histories, ICU admissions, and risk factors were investigated through their medical records. Susceptibility testing was performed using the MicroScan method (MicroScan Walk-Away, Dade Behring, West Sacramento, CA, USA) and the results were interpreted according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines [12].

The severity of underlying medical conditions was classified using McCabe and Jackson scores that categorize conditions as fatal, ultimately fatal, or non-fatal [13].

Outcome assessments

The hospital days from the time of admission to the occurrence of S. aureus bacteremia were measured for each patient. The days after the appearance of bacteremia to discharge were also compared between the two groups. Data on the total costs of hospitalization were collected from the central financial service at Kyung Hee University Medical Center and were adjusted to the 2008 US dollar. Hospital costs were categorized as the cost of hospital stay, laboratory tests, care, and treatments. The cost of hospital stay included the costs derived from administration, clerical support, housekeeping, and medical records. The costs associated with care included the cost of physician care, nursing care, and consultations. Treatment costs were based on the total drug costs, cost of materials such as catheters and implanted devices, and costs of procedures, including operations, dialysis, respiratory care, and rehabilitation.

According to the report of the Korean Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (KONIS), MRSA constituted 70% of isolated pathogens in the healthcare-associated infection (HCAI) study in Korea [14]. Based on these data, we did not isolate the patients with MRSA infection but performed only standard precautions and surveillance methods. Consequently, the costs did not include MRSA quarantine costs.

Death was considered to be related to bacteremia if the patient had positive S. aureus blood cultures and persistent clinical signs and symptoms of sepsis [15]. Vital status 30 days after the onset of bacteremia was also assessed.

Statistical analysis

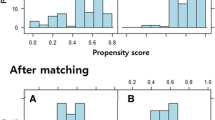

The results were analyzed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and SPSS for Windows version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The t-test was used to compare the MRSA and MSSA groups. Qualitative variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test and Pearson’s chi-square test. We matched propensity scores to evaluate the health outcomes of MRSA infection compared with those of MSSA infection. To model the probability of MRSA infection, logistic regression was used. Age, sex, admission route, ICU admission, epidemiologic classification (whether the infection was community-associated or healthcare-associated), clinical condition (primary or secondary bacteremia), use of devices (central venous catheter, urinary catheter, or ventilator), and the number of underlying diseases or conditions such as diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), liver cirrhosis (LC), solid tumor, renal disease with dialysis, or being immunocompromised were considered as independent variables for the propensity scores. Patients who were infected with MRSA were matched to patients in the MSSA group by the greedy matching algorithm. We used a 5–1 computerized greedy matching algorithm, which was developed for the SAS package for this study [16]. In this greedy matching algorithm, the MRSA cases were matched to MSSA controls with regard to five digits of the propensity score, and those that did not match were then attempted to be matched relative to four digits, and so on, down to one digit. If no single-digit match was found for an MRSA case, it was excluded from the analysis. After propensity score matching, McNemar’s test and paired t-tests were used to compare both groups. Also, we compared the appropriateness of therapy between the MRSA and MSSA groups after propensity score matching.

Results

A total of 167,488 patients were admitted to the hospital during the study period and 266 patients with S. aureus bacteremia were analyzed for this study. Among them, 145 patients had MRSA bacteremia (54.3%) and 121 patients had MSSA bacteremia (45.7%). The differential characteristics of patients with MRSA bacteremia and those with MSSA bacteremia are described in Table 1. Patients with MRSA bacteremia were older than those with MSSA bacteremia (mean age, 62.1 vs. 54.8 years; P = 0.03), but the sex distribution for both groups was similar (P = 0.67). More patients with MRSA bacteremia had underlying comorbidities such as COPD (P = 0.01), while more patients with MSSA bacteremia had underlying comorbidities such as LC (P = 0.01) or had undergone immunosuppressive therapy (P = 0.002). Furthermore, patients who were admitted to the ICU were more likely to be having MRSA infection (71.2 vs. 28.8%; P = 0.001). Among patients with community-associated bacteremia, MSSA bacteremia was more prevalent than MRSA bacteremia (78.4 vs. 21.6%; P < 0.001). The use of invasive medical devices such as a central line, Foley catheter, or ventilator was associated with the occurrence of MRSA bacteremia. Of the patients with MRSA bacteremia, 28% compared with 12% of patients with MSSA bacteremia had used a ventilator (P < 0.001), 63% of patients with MRSA bacteremia compared with 46% of patients with MSSA bacteremia had a central line (P < 0.001), and 54% of patients with MRSA bacteremia compared with 19% of patients with MSSA bacteremia had received a urinary catheter (P < 0.001) (data was not shown).

The case fatality rates in the unmatched total populations of MRSA and MSSA were 21.4 and 28.9%, respectively. This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.16).

Propensity score matching

In this study, a total of 106 patients, or 53 pairs, were matched on the basis of the propensity score to adjust for potential differences between MRSA and MSSA bacteremia. The result of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was 0.122, and the C-value was 0.865. Paired t-tests were used to compare characteristics between the matched pairs. The baseline characteristics of both groups were similar after propensity matching (Table 2). Patients with MRSA bacteremia had a median of 0.8 comorbidities and patients with MSSA bacteremia had a median of 0.8 comorbidities upon admission (P = 0.89).

Patients with MRSA bacteremia were more likely than those with MSSA bacteremia to have stayed longer in the hospital before the development of bacteremia (mean 25.0 vs. 6.1 days; P < 0.01). But after developing bacteremia, the differences in hospital stay lengths were not statistically significant (mean 35.0 vs. 28.7 days; P = 0.33). The average total length of hospital stay remained significantly longer for patients with MRSA bacteremia as compared to MSSA bacteremia (mean 59.9 vs. 34.8 days; P = 0.01).

After adjustment for age, sex, epidemiologic classification (whether the infection was community-associated or healthcare-associated), clinical condition (primary or secondary bacteremia), use of devices (central venous catheter, urinary catheter, or ventilator), and the number of underlying diseases according to propensity score matching, the hospital costs for the two groups of patients with S. aureus bacteremia were compared. Costs for patients with MRSA bacteremia were higher than those of patients with MSSA bacteremia, but this difference was not statistically significant ($9,369.6 vs. $8,355.8; P = 0.62).

McNemar’s test was used to test the comparison of mortality outcomes between the two groups (Table 3). A total of 35 pairs had a concordant outcome (31 pairs survived and 4 died) and 18 pairs had a discordant outcome. Therefore, methicillin resistance was not considered to be an independent predictor of mortality in patients with S. aureus bacteremia (P = 0.48). Typical empiric therapy in our hospital for patients with MSSA infection was a beta-lactam antibiotic, such as cefazolin or nafcillin, and glycopeptide antibiotics like vancomycin and teicoplanin were used for the patients with MRSA infection. Receipt of concordant empirical therapy was slightly lower in patients with MRSA infection than in those patients with MSSA infection, but the difference was not statistically significant (41 pairs vs. 48 pairs; P = 0.19).

Discussion

We have presented evidence that patients with MRSA bacteremia have significantly longer hospitalization stays but are no more likely to pay higher hospital costs or to die due to the infection than are patients with MSSA bacteremia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Korea using propensity score matching to compare hospital costs between cases of MRSA bacteremia and MSSA bacteremia.

According to the study conducted by Cosgrove et al. [17], MRSA bacteremia was a significant predictor of increased length of hospitalization and the length of hospital stay attributable to MRSA infection was 2.2 days. Other studies that evaluated outcomes related to MRSA bacteremia indicated that MRSA bacteremia was associated with a longer length of hospital stay after the onset of bacteremia [18, 19]. In the current study, MRSA bacteremia affected the total length of hospital stay (P = 0.01) but, interestingly, the difference in the length of stay after bacteremia was not significant in patients with MRSA bacteremia when compared to patients with MSSA bacteremia. This result might arise because of differences among national medical systems. In the United States, each patient is classified into a Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) on the basis of clinical information and hospitals are paid a pre-determined rate for each Medicare admission, which is called the Medicare Prospective Payment System. DRG-based prospective payment systems result in the transition to more outpatient services from inpatient services [20]. But in Korea, where this investigation was conducted, patients pay providers for services under a Fee-For-Service (FFS) reimbursement system that may, in part, be the cause of the lack of difference between the lengths of stays after bacteremia between the MRSA and MSSA groups.

Many previous studies investigating the effects of MRSA infection compared with MSSA infection have shown conflicting results [21–23]. In a previous analysis [24], MRSA infection was the most significant predictor of delayed treatment and delayed treatment was found to be an independent predictor of infection-related mortality. However, in another study, the difference in MRSA bacteremia-related mortality between appropriate and inappropriate empirical treatment was not significant [25]. This disagreement may be the result of methodological differences between studies, small sample sizes, confounding factors, and a broad range of underlying comorbid conditions, etc. Therefore, we used propensity score matching to control for confounding factors as much as possible. After adjustment for the effects of other variables, the mortality rate was not significantly higher in patients with MRSA infection (P = 0.48). These findings agree with those of previous studies [26, 27], which found that mortality due to S. aureus was not more frequent in patients with MRSA bacteremia.

Variables relating to a patient’s prior clinical condition could influence the outcome of bacteremia. In this study, we closely evaluated risk factors for infection with MRSA. Furthermore, the use of propensity score matching allowed us to define the impacts of methicillin resistance on mortality, length of hospitalization, and hospital costs. When we matched the MRSA and MSSA groups by propensity score, methicillin resistance was not a significant predictor of mortality. Our data suggest that the association of underlying disease and host variables could result in an overestimation of MRSA virulence. We believe that strict control of confounding variables, such as the severity of underlying disease, is important because these variables could distort comparisons of outcomes between MRSA and MSSA infections.

In a meta-analysis [17], methicillin resistance was associated with increases in hospital costs of more than $7,000 over costs of patients with MSSA bacteremia. At the national level, annual admission cases for the treatment of patients hospitalized with MRSA was 120,000 and the annual cost for MRSA treatment in the United States was $15 billion [28]. In the current study, Korean patients with infections due to MRSA incurred hospital costs of an average of $9,369.60 per person, but there was no significant difference between this figure and that of MSSA patients (P = 0.62).

A limitation of our study is that only measured covariates were controlled and there may be additional confounding factors not accounted for. This problem is always a limitation in studies without randomized controlled methods, including our study. Furthermore, our results reflect cost data for the hospital where the MRSA infections were identified and the costs may be different in other Medicare and insurance systems.

In summary, this study indicated that MRSA bacteremia was not associated with higher risks of mortality or a substantial increase in hospital costs, but that it was associated with an increased length of hospital stay compared to MSSA bacteremia. These findings remained significant even after adjustment for comorbidities. Because the prevalence of MRSA infection has increased worldwide [29], the information provided by this study may help clinicians and policymakers to derive methods to control the impacts of MRSA infection on medical personnel, health policymakers, and patients.

References

Fridkin SK, Hageman JC, Morrison M, Sanza LT, Como-Sabetti K, Jernigan JA, Harriman K, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Farley MM; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Program of the Emerging Infections Program Network. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1436–44.

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:470–85

Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK; Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–71.

Herold BC, Immergluck LC, Maranan MC, Lauderdale DS, Gaskin RE, Boyle-Vavra S, Leitch CD, Daum RS. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA. 1998;279:593–8.

Kim KM, Yoo JH, Choi JH, Park ES, Kim KS. The nationwide surveillance results of nosocomial infections along with antimicrobial resistance in intensive care units of sixteen university hospitals in Korea, 2004. Korean J Nosocomial Infect Control. 2006;11:79–86.

Haley RW, White JW, Culver DH, Hughes JM. The financial incentive for hospitals to prevent nosocomial infections under the prospective payment system. An empirical determination from a nationally representative sample. JAMA. 1987;257:1611–4.

Stone PW, Larson E, Kawar LN. A systematic audit of economic evidence linking nosocomial infections and infection control interventions: 1990–2000. Am J Infect Control. 2002;30:145–52.

Harbarth S, Rutschmann O, Sudre P, Pittet D. Impact of methicillin resistance on the outcome of patients with bacteremia caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:182–9.

Joffe MM, Rosenbaum PR. Invited commentary: propensity scores. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:327–33.

Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16:128–40.

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, Craven DE, Flynn P, O’Grady NP, Raad II, Rijnders BJ, Sherertz RJ, Warren DK. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45.

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Wayne: NCCLS; 2002.

McCabe WR, Jackson GG. Gram-negative bacteremia. Arch Intern Med. 1962;110:847–55.

Park YJ, Jeong JS, Park ES, Shin ES, Kim SH, Lee YS. Survey on the infection control of multidrug-resistant microorganisms in general hospitals in Korea. Korean J Nosocomial Infect Control. 2007;12:112–21.

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–55.

Parsons LS. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using Greedy matching techniques. In: Proceedings of the 26th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference, Long Beach, California, 22–25 April 2001. Cary: SAS Institute; 2001

Cosgrove SE, Qi Y, Kaye KS, Harbarth S, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. The impact of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia on patient outcomes: mortality, length of stay, and hospital charges. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:166–74.

Lodise TP, McKinnon PS. Clinical and economic impact of methicillin resistance in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;52:113–22.

Reed SD, Friedman JY, Engemann JJ, Griffiths RI, Anstrom KJ, Kaye KS, Stryjewski ME, Szczech LA, Reller LB, Corey GR, Schulman KA, Fowler VG Jr. Costs and outcomes among hemodialysis-dependent patients with methicillin-resistant or methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:175–83.

Lee H, Lee H, Lee K-H, Wan TTH. Comparing efficiency between public and private hospitals in South Korea. Int J Public Policy. 2008;3:430–42.

Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:53–9.

Whitby M, McLaws ML, Berry G. Risk of death from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a meta-analysis. Med J Aust. 2001;175:264–7.

Mylotte JM, Tayara A. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: predictors of 30-day mortality in a large cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1170–4.

Lodise TP, McKinnon PS, Swiderski L, Rybak MJ. Outcomes analysis of delayed antibiotic treatment for hospital-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1418–23.

Kim SH, Park WB, Lee KD, Kang CI, Bang JW, Kim HB, Kim EC, Oh MD, Choe KW. Outcome of inappropriate initial antimicrobial treatment in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:489–97.

Melzer M, Eykyn SJ, Gransden WR, Chinn S. Is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus more virulent than methicillin-susceptible S. aureus? A comparative cohort study of British patients with nosocomial infection and bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1453–60.

Soriano A, Martínez JA, Mensa J, Marco F, Almela M, Moreno-Martínez A, Sánchez F, Muñoz I, Jiménez de Anta MT, Soriano E. Pathogenic significance of methicillin resistance for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:368–73.

Rojas EG, Liu LZ. Annual cost for the treatment of patients hospitalized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States. Value Health. 2005;8:308.

Hansen S, Schwab F, Asensio A, Carsauw H, Heczko P, Klavs I, Lyytikäinen O, Palomar M, Riesenfeld-Orn I, Savey A, Szilagyi E, Valinteliene R, Fabry J, Gastmeier P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Europe: which infection control measures are taken? Infection. 2010;38:159–64.

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S.Y., Son, J.S., Oh, I.H. et al. Clinical impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia based on propensity scores. Infection 39, 141–147 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-011-0100-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-011-0100-1