Abstract

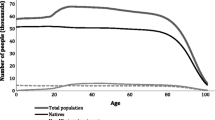

In this paper, we present the estimates of the fiscal transfer to immigrants from native-born Canadians. The fiscal transfer is the amount of money that immigrants absorb in public services less the amount that they pay in taxes, suitably adjusted for scale effects in public provision of services, life cycle effects in tax payment, and so on. Our work builds on previous works in the literature, updating from the last scholarly work in this area by Akbari (Can Public Policy 15(4): 424–435, 1989) with new and richer data. Akbari found on the basis of the 1981 Census data a small fiscal transfer from immigrants to the native-born amounting to about $500 per year per immigrant. Over time, the composition and income attainment of immigrants has evolved somewhat unfavorably for immigrants, and we find on the basis of the 2006 census data, a small fiscal transfer from the native-born to immigrants of about $500 per year per immigrant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Measuring the consumption of public services, Akbari (1989) only looks at government transfer payments, educational services, and health care services.

There are also a number of errors and inconsistencies in their analysis, and this study presents a corrected estimate of the fiscal transfer that they sought to estimate.

Total income refers to total money income received from the following sources during the calendar year 2005 by persons 15 years of age and over: wages and salaries (total); net farm income; net non-farm income from unincorporated business and/or professional practice; child benefits; old age security pension and guaranteed income supplement; benefits from Canada or Quebec Pension Plan; benefits from employment insurance; other income from government sources; dividends, interest on bonds, deposits and savings certificates, and other investment income; retirement pensions, superannuation, and annuities including those from RRSPs and RRIFs; other money income.

This is likely to overestimate (underestimate) the fiscal cost (benefit) of immigration because older cohorts of immigrants, on average, have higher incomes relative to more recent cohorts.

This column is needed to calculate the numbers in column (7).

Grubel and Grady (2011) find the ratio of investment income between Canadian-borns and natives (1987–2004) to be 41 %. They discount it by 72 % to arrive at the ratio they use for corporate income tax (41*72 = 30 %).

The numbers reported in Table 3 are consolidated and exclude intergovernmental transfers.

The numbers are from Statistics Canada, Table 385-0001.

Assuming that immigrants benefit from government spending on labor, employment, and immigration by more than 20 % is not going to significantly change our results. For instance, a 50 % higher benefit, compared to 20 %, only changes our estimated fiscal transfer by $22.5. In addition, it should be noted that immigrants to Canada pay a Right of Permanent Residence Fee and also an application fee to become a Canadian permanent resident. These fees currently around $1,000/per person and add up to about $200 million in revenues annually. This partly offsets the expenses on immigration that are only enjoyed by immigrants.

According to the figures of government expenditures provided by Statistics Canada, total spending on social assistance alone amounted to 55 % of spending on social services at all government levels in 2006.

The expenditures on national defense in 2005/2006 is estimated to be $14.7 billion dollars (Defence Budgets 1999–2007). We use expenditures on research establishments as a substitute for science and technology.

Looking at Table 2 in the study by Grubel and Grady, where they estimate the difference in average per-capita taxes paid by immigrants [1987–2004] and all Canadian residents, there are several inconsistencies between the text and the numbers that appear in the table. (1) The text (page 6, the line before the end line) claims that “the ratio for corporate income tax is assumed to be 30 %” while the ratio used in the table is 20 %. (2) To justify the use of 30 % as the ratio for corporate income taxes (although they end up using 20 % in their table), Grubel and Grady argue that “according to the PUMF data, the [recent] immigrants' investment income is only 41 % of the average of all Canadians and that this probably includes a disproportionate amount of investment other than corporate stocks.” However, a closer examination of the PUMF data reveals that this number is in fact 46 %. (3) Grubel and Grady claim that “it was assumed that the amounts paid as property and related taxes and other taxes were related to total income.” However, the ratio used in Table 2 to calculate the property and related taxes paid by immigrants is 41 %, which has nothing to do with the total income ratio (which is 72 % as calculated in Table 1 by Grubel and Grady).

This is consistent with Auerbach and Oreopoulos (2000). They also conclude that “the overall fiscal impact of immigration is unclear. Whether there is a gain or loss depends on the extent to which government purchases rise with the immigration population” which, in turn, depends on the proportion of government purchases that are “public” in nature.

Examples include the studies by the Ornstein and Sharma (1983); Li (1988, 1992); Economic Council of Canada (1991); Boyd (1992); Abbott and Beach (1993); Christofidies and Swidinsky (1994); Reitz and Breton (1994); Bloom et al. (1995); Baker and Benjamin (1997); Reitz and Sklar (1997); Pendakur and Pandakur (1998); Hum and Simpson (1999); Reitz et al. (1999), and Thompson (2000), among others.

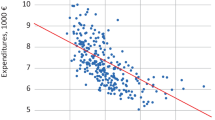

Reviewing the figures provided by Statistics Canada on government finances, there are significant changes in government finances over time. For instance, on a per-capita basis, spending on social services in Canada has increased by 80 % between 1989 and 2007. In comparison, health expenditures and expenditures on environment have increased by 136 and 116 %, respectively. On the other hand, spending on the labor, employment, and immigration has declined by 17 % (Statistics Canada 2007). Similarly, looking at consolidated revenues at all levels of government, the total personal income tax revenue collected by the government has increased by 140 % between 1989 and 2009.

References

Abbott, M. G., & Beach, C. M. (1993). Immigrant earnings differentials and cohort effects in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics, 1993, 505–524.

Akbari, A. H. (1995). The impact of immigrants on Canada's treasury, circa 1990. In D. J. DeVoretz (Ed.), Diminishing returns: the economics of Canada's recent immigration policy (pp. 111–127). Toronto: C. D. Howe Institute.

Akbari, A. H. (1991). The public finance impact of immigrant population on host nations: some Canadian evidence. Social Science Quarterly, 72(2), 334–346.

Akbari, A. H. (1989). The benefit of immigrants to Canada: evidence on tax and public services. Canadian Public Policy, 15(4), 424–435.

Anderson, K., and L.A. Winters (2008) The Challenge of reducing international trade and migration barriers, CEPR Discussion Paper 6760, March.

Auerbach, A., & Oreopolis, P. (2000). The fiscal impact of US immigration: a generational accounting perspective. In J. Poterba (Ed.), Tax policy and the economy (Vol. 14). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Auerbach, A., Gokhale, J., & Kotlikoff, L. (1991). Generational accounts: a meaningful alternative to deficit accounting. In D. Bradford (Ed.), Tax Policy and the Economy, vol. 5. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Baker, M., & Benjamin, D. (1997). Ethnicity, foreign birth and earnings: a Canada/US comparison. In M. G. Abbott, C. M. Beach, & R. P. Chaykowski (Eds.), Transition and Structural Change in the North American Labour Market (pp. 281–313). Kingston, ON: John Deutsch Institute and Industrial Relations Centre, Queen’s University.

Baker, M., & Benjamin, D. (1995). The receipt of transfer payments by immigrants to Canada. Journal of Human Resources, 30, 650–676.

Bloom, D., Grenier, G., & Gunderson, M. (1995). The changing labour market position of Canadian immigrants. Canadian Journal of Economics, 28(4b), 987–1005.

Boyd, M. (1992). Gender, visible minority and immigrant earnings inequality: reassessing an employment equity premise. In V. Satzewich (Ed.), Deconstructing a Nation: Immigration, Multiculturalism and Racism in the 1990s Canada (pp. 279–321). Toronto: Garamond Press.

Chellaraj, G., Maskus, K. E., & Mattoo, A. (2008). The contribution of skilled immigration and international graduate students to US innovation. Review of International Economics, 16(3), 444–462.

Christofides, L. N., & Swidinsky, R. (1994). Wage determination by gender and visible minority status: evidence from the 1989 LMAS. Canadian Public Policy, 22(1), 34–51.

Defence budgets 1999–2007. National Defense and the Canadian Forces. http://www.forces.gc.ca/site/reports-rapports/budget05/back05-eng.asp

Dustmann, C., Frattini, T., Preston, I. (2008). The effect of immigration along the distribution of wages. (Discussion Paper Series 03/08). London, UK, Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration.

Economic Council of Canada. (1991). Economic and social impacts of immigration. Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada.

Fleury, D. (2007). A study of poverty and working poverty among recent immigrants to Canada. Ottawa: Human Resources and Social Development Canada.

Grubel, H., and P. Grady. (2011) Immigration and the Canadian Welfare State 2011, Fraser Institute.

Head, K., & Ries, J. (1998). Immigration and trade creation: Econometric evidence from Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics, Canadian Economics Association, 31(1),47–62.

Hum, D., & Simpson, W. (1999). Wage opportunities for visible minorities in Canada. Canadian Public Policy, 25(3), 379–394.

Hunt, J., & Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2010). How much does immigration boost innovation? American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(2), 31–56.

Kremer, M., and S. Watt (2006) “The Globalization of Household Production,” Working Paper 2008-0086, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University.

Li, P. S. (1988). Ethnic inequality in a class society. Toronto: Wall and Thompson.

Li, P. S. (1992). Race and gender as bases of class fractions and their effects on earnings. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 29, 488–510.

Mattoo, A., & Mishra, D. (2009). Foreign professionals in the United States: regulatory impediments to trade. Journal of International Economic Law, 12(2), 435–456.

National Research Council. (1997). The new Americans: economic, demographic, and fiscal effects of immigration. Washington: National Academy Press.

Ornstein, M. D., & Sharma, R. D. (1983). Adjustment and economic experience of immigrants in Canada: an analysis of the 1976 longitudinal survey of immigrants. A report to employment and immigration Canada. Toronto: York University.

Peri, G., & Spaber, C. (2009). Task specialization, immigration and wages. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 135–169.

Oreopoulos, P. (2009) Why do skilled immigrants struggle in the labor market? A field experiment with six thousand résumés, NBER working paper No. 15036.

Ortega, F., & Peri, G. (2009). The causes and effects of international labor mobility: evidence from OECD Countries 1980–2005 Human Development Research Paper, No. 6. New York: United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Pendakur, K., & Pendakur, R. (1998). The colour of money: earnings differentials among ethnic groups in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics, 31(3), 518–548.

Pendakur, K., and S. Woodcock (2010) Glass ceilings or glass doors? Wage disparity within and between firms, Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, January 2010, Vol, 28, No.1.

Reitz, J. G. (2001). Immigrant skill utilization in the Canadian labour market: implications of human capital research. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 2(3), 347–378.

Reitz, J. G., Frick, J. R., Calabrese, T., & Wagner, G. G. (1999). The institutional framework of ethnic employment disadvantage: a comparison of Germany and Canada. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 25(3), 397–443.

Reitz, J. G., & Sklar, S. (1997). Culture, race, and the economic assimilation of immigrants. Sociological Forum, 12(2), 233–277.

Reitz, J. G., & Breton, R. (1994). The illusion of difference: realities of ethnicity in Canada and the United States. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Ratha, D., S. Mohapatra, and E. Scheja (2011) Impact of migration on economic and social development: a review of evidence and emerging issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5558.

Simon, J. 1981 What immigrants take from and give to the public coffers. US Immigration Policy and the National Interest: Appendix D to Staff Report of the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy.

Statistics Canada (2007) Government spending on social services. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/070622/dq070622b-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada (2013) 2011 National household survey: immigration, place of birth, citizenship, ethnic origin, visible minorities, language and religion, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/130508/dq130508b-eng.htm

Thompson, E. N. (2000) Immigrant occupational skill outcomes and the role of region specific human capital, Unpublished ms., Human Resources Dev. Canada.

UNDP (United Nations Development Program). (2009). Overcoming barriers: human mobility and development. New York: United Nations Development Program.

Van der Mensbrugghe, D., & Roland-Holst, D. (2009). Global economic prospects for increasing developing country migration into developed countries, Human Development Research Paper, No. 50. New York: United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Winters, L. A., Walmsley, T., Wang, Z. K., & Grynberg, R. (2003). Liberalizing temporary movement of natural persons: an agenda for the development round. The World Economy, 26(8), 1137–1161.

World Bank, (2006). Global economic prospects 2006: Economic implications of remittances and migration. Washington DC, World Bank.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council through its Metropolis program and Metropolis British Columbia for institutional support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Javdani, M., Pendakur, K. Fiscal Effects of Immigrants in Canada. Int. Migration & Integration 15, 777–797 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-013-0305-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-013-0305-5