Abstract

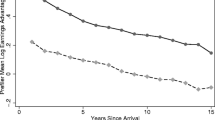

Using data from the 1996, 2001, and 2006 years of the Hong Kong Population Census, this paper reported the nativity earnings gap among a synthetic cohort of immigrant and native male Chinese employees in Hong Kong. Consistent with previous research, we found earnings divergence for all workers. However, this earnings divergence masked a reverse trend for low-skilled workers. Over time, low-skilled immigrant workers gained earnings assimilation with low-skilled native workers, but high-skilled immigrant workers did not gain assimilation with high-skilled native workers. A decomposition analysis suggested that the relative skill prices cannot explain the overtime change in the relative mean-earnings gaps by nativity. Further separating pre- and postmigration education of immigrants did not improve the explanatory power of the relative skill prices. Our results for Hong Kong are consistent with the findings from recent research on the economic assimilation of low-skilled immigrants in other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 20 % random sample is drawn by the first author from the full datasets of the Population Censuses/by-censuses. The design of the 1991 and 2001 Population Census comprised a complete but simple enumeration of all persons on their basic characteristics such as age and sex, and a detailed 1/7 sample enquiry on a broad range of socio-economic characteristics of the population. The design of the 1996 Population by-census and the 2006 Population by-census were a 1/7 and 1/10 sample enquiry on a broad range of socio-economic characteristics of the population, respectively.

The Chinese ethnicity made up 95 % of its population in 2006. Other ethnic groups comprised 1.6 % Filipinos, 1.3 % Indonesians, and 2 % of a variety of ethnicities, including Caucasian, Indian, Nepalese, Japanese, Thai, Pakistani, and other Asian (Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department 2006).

The minimum work age was changed to 18 years in 2008.

We also conducted the analysis using the age range of 25 to 50 to restrict the sample to individuals who had completed their education and were economically active at the time they were first observed. The results were virtually identical to those reported here.

Hong Kong’s education system contains 6 years of primary school, 3 years of lower secondary school, and 2 years of upper secondary school. After secondary school, students can either study craft courses in technical institutions, or attend two years of matriculation courses, which prepare them for college (i.e. first degree programs). College education spanned 3 years during the period we studied.

Results are available from the authors upon request.

We defined managers and professionals’ occupations as managers and administrators; professionals and associate professionals. Other occupations include clerks, service workers and shop sales workers, skilled agricultural and fishery workers, craft and related workers, plant and machine operators and assemblers, and elementary occupations.

Average earnings for each industry in 1996, 2001, and 2006 are available upon request.

As discussed earlier and shown in Table 1, there were some changes in the average years of education over time for both immigrants and natives. Even if we restrict our sample to the cohort of workers ages 25 years and above (results not shown), who were likely to have completed their education, there are still some, albeit small differences between t and t + 1. It is reasonable that the average levels would increase over time because individuals age 15 years and above will continue education. However, sample selection could also change the mean levels of education of the artificial cohorts we track. For example, if immigrants with more education left Hong Kong after a short period of stay and only those with relatively less education remained, the average education level for immigrants should become lower over time, which was the case in our data. It is also plausible that the pursuit of further education (possibly due to occupational needs) for immigrants and natives are different. Nonetheless, the changes were less than a year in our study.

Restaurant business hired the most immigrant male employees in all Census years we studied: about 11.8 % in 1996, 14.4 % in 2001, and 19.0 % in 2006.

Returns to experience in China were less than half of the returns to experience in Hong Kong in the first 5 years after arrival. Furthermore, the returns to experience in China became statistically insignificant at the later time points. It is interesting that the returns to experience in Hong Kong actually became negative for Chinese immigrants. This seems to indicate a devaluation of experience by their employers, an improved quality of education in the host society, a lack of internal labor market opportunities, an obsolescence of accumulated human capital and effects of aging (Casanova 2010), or some combination of these factors. Just as we observed for all immigrants, the returns to foreign work experience for high-skilled immigrants became very small and even insignificant at Time 3. There was also a negative return to local work experience for high-skilled Chinese immigrants. It is even more interesting that the return to local work experience was positive for low-skilled Chinese immigrants in their first 5 years in Hong Kong. Even at Time 2 and Time 3, the estimated returns to work experience, regardless of whether controls were included for industrial and occupational differences, were very similar and positive for both Chinese-immigrant and native low-skilled workers. This might explain the earnings convergence that we observed for this group.

This might due to the high-skilled immigration policy, which ensured that only those who possessed skills that would contribute substantially to Hong Kong’s labor force were recruited and permitted to enter Hong Kong’s labor market.

References

Akresh, I. R. (2006). Occupational mobility among legal immigrants to the United States. International Migration Review, 40(4), 854–884.

Basilio, L., & Bauer, T. (2010). Transferability of human capital and immigrant assimilation: An analysis for Germany. IZA Discussion Paper, 4716.

Borjas, G. J. (1985). Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(4), 463–489.

Borjas, G. J. (1995). Assimilation and changes in cohort quality revisited: What happened to immigrant earnings in the 1980s? Journal of LaborEconomics, 13(2), 201–245.

Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, U.S. Department of State. (2011). Background note: Hong Kong. Accessed on September 22, 2011 from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2747.htm

Capps, R., Fix, M., Passel, J. S., Ost, J., & Perez-Lopez, D. (2003). A profile of the low-wage immigrant work force. Urban Institute: Washington D.C.

Card, D. (2005). Is the new immigration really so bad? Economic Journal, 115(507), F300–F323.

Casanova, M. (2010). The wage process of older workers. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics. Los Angeles: University of California.

Chiswick, B. R. (1978). The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. Journal of Political Economy, 86(5), 893–921.

Friedberg, R. (2000). You can’t take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(2), 221–251.

Hall, M., & Farkas, G. (2008). Does human capital rais earnings for immigrants in the low-skill labor market? Demography, 45(3), 619–639.

Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department. (2006). 2006 Population by-census: Summary results. Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department.

Hong Kong Immigration Department. Retrieved on December 7, 2011 from http://www.immd.gov.hk/ehtml/faq_asmtp.htm

Jaeger, D.A. (2007). Skill differences and the effect of immigrants on the wages of natives, College of William and Mary, mimeo.

Lam, K. C., & Liu, P. W. (1998). Immigration and the economy of Hong Kong. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

Lam, K. C., & Liu, P. W. (2002a). Earnings divergence of immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(1), 86–101.

Lam, K. C., & Liu, P. W. (2002b). Relative returns to skills and assimilation of immigrants. Pacific Economic Review, 7(2), 229–243.

Liu, P. W., Zhang, J. S., & Chong, S. C. (2004). Occupational segregation and wage differentials between natives and immigrants: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of Development Economics, 73(1), 395–413.

Massey, D. S., Mooney, M., Torres, K. C., & Charles, C. Z. (2007). Black immigrants and black natives attending selective colleges and universities in the United States. American Journal of Education, 113(2), 243–271.

Pong, S.-L., & Tsang, W. K. (2010). The educational progress of mainland Chinese immigrant students in Hong Kong. Research in Sociology of Education, 17, 201–230.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2006). Immigrant America: A portrait. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zeng, Z., & Xie, Y. (2004). Asian Americans’ earnings disadvantage reexamined: The role of place of education. American Journal of Sociology, 109(5), 1075–1108.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ou, D., Pong, Sl. Human Capital and the Economic Assimilation of Recent Immigrants in Hong Kong. Int. Migration & Integration 14, 689–710 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0262-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0262-4