Abstract

“Investment in energy efficiency: do the characteristics of firms matter?” In their famous 1998 paper, DeCanio and Watkins raised the question and answered it affirmatively. Our paper addresses a parallel question: “Investment in energy efficiency: do the characteristics of investments matter?” To answer this question, we first describe our new investment decision-making model, applicable to all investment types. We then discuss our research results, based on questionnaires submitted to finance managers of 35 major electricity consumers in various commercial and industrial sectors. We show how characteristics other than profitability play an important role in investment choices. The investment category influences profitability evaluation, profitability requirement, and, ultimately, the decision made. For half of the firms in our study, energy-efficiency investments did not exist as a category. However, wide diversity regarding investment behavior is observed between firms. Our findings lead to a different explanation of the energy-efficiency gap and open the way for a new approach to promoting energy-efficiency investments, which is briefly discussed in the conclusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to mainstream neoclassical economics, investment decisions are strictly based on investment profitability, and firms should undertake all investments with a positive net present value.Footnote 1 Energy-efficiency investments are not decided upon by profit-seeking firms because of their low real profitability (among others, Anderson and Newell 2004; Golove and Eto 1996; Jaffe and Stavins 1994; Sutherland 1991; Van Soest and Bulte 2001) or because information problems prevent price indications from reaching decision makers (Jaffe and Stavins 1994; Sorrell, et al. 2000) or force organizations to define sub-optimal routines (DeCanio 1993; Quirion 2004; Ross 1986).

According to the economic perspective on market barriers to energy-efficiency investments, information asymmetry, an organizational failure, is partially responsible for underinvestment in energy efficiency. In organizations, middle management is closer to operations and is therefore better informed than upper management. Yet, middle management decisions are biased by bounded rationality and opportunism. This situation is known as moral hazard, a form of information asymmetry theorized by the agency theory. To reduce the potentially negative consequences of such a situation for their organization, upper management fixes a priori rules, or routines (DeCanio 1993; Stern and Aronson 1984), which frame and control decision-making. These routines can strongly influence organizations’ investment decisions. For instance, Sorrell et al. ((2000): 46) consider that “most decisions are a result of applying a set of rules to a situation, rather than a systematic analysis of alternatives.” Pay-back or hurdle-rate requirements for investment are examples of such routines, as described by DeCanio: “hurdle rates can be set with an eye towards the problems of control of a large organization, not just to correspond to the firm’s cost of capital” (DeCanio 1993: 908). DeCanio mentions a survey conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) which showed that “the median pay-back required for one class of energy investment was 2 years. A payback of 2 years for a project with a 10-year lifetime is equivalent to a post-tax real rate of return of 56 %” (DeCanio, idem). The same reasons may explain the frequent procedure of capital rationing by firms, as described by Ross (1986). Importance of routines, especially budgetary routines, in investment decision-making is also underlined by Quirion (2004). These routines translate into sub-optimal investment decisions, i.e., those where investments with profitability higher than the cost of capital for a company are not being decided upon, in contradiction with the prescriptions of the conventional theory of investment.

In real life, firms do not make their investment decisions based on the conventional neoclassical theory of investment. Decision-making research depicts a complex reality of generalFootnote 2 investment decision making. Energy economics research has shown that factors other than profitability—factors which are not related to market or organization failures—do interfere in energy-efficiency investment decisions. In their 1998 paper, DeCanio and Watkins studied decisions by firms to join the EPA’s program Green Lights. Decision to join Green Lights may be thought of as a signal of a firm’s willingness to undertake a program of investments in lighting efficiency. According to the conventional theory of investment, characteristics of the firms that join should not influence their decision to join Green Lights and to commit to energy efficiency investments. On the contrary, results of DeCanio and Watkins’ empirical study show that the characteristics of firms—such as size, financial performance, sector, or geographical location—“do influence the probability of a company’s joining the Green Lights program” (DeCanio and Watkins 1998: 103).

In contradiction with conventional theory, investment strategic character, or nature, also influence investment decisions. This is the stance of our paper. Based on the Dutton et al. (1989) conceptual framework, characteristics of an investment decision can be classified into two categories: analytic characteristics and content characteristics. Analytic and content characteristics determine investment strategic character. Decision-making research has studied the influence of analytic characteristics on decision making, but the ways in which content characteristics influence investment decisions has generally been neglected. However, as shown by the small amount of existing research, investment content does matter in investment decision making.

By linking the fields of strategy and finance, we have built a methodological tool, based on content characteristics, to better understand an investment strategic nature—or strategicity—and to measure it. Based on this theoretical framework, we conducted an empirical survey in Geneva, Switzerland, from 2006 to 2007. Survey results show the influence of strategic considerations on general investment decision making and the often mediocre strategic importance of energy-efficiency investments for businesses.

The goal of this paper is to describe our findings and their implications for researchers, practitioners, and policy makers.

To address this goal, the paper is organized into three parts. The first part describes our theoretical framework; the second part describes our research methodology, and the third part discusses the results of the research, which can be classified into two themes: general corporate investment behavior and energy-efficiency investment behavior. The conclusion will briefly discuss the implications of our findings in the field of energy efficiency.

Investment decision making

The theoretical framework described in this part is divided in two sections. The first section summarizes our model of investment decision making, a model useful to understanding, or even influencing, any type of investment decision (Fig. 1). The second section focuses on analyzing and defining the strategic nature of an investment.

A new model of investment decision making

Analyzing the large amount of research in the fields of decision making and organizational finance leads one to define investment decision making as a complex process, one which is influenced by many factors. Rooted in an extensive exploration of the literature, our model of investment decision making explains which factors play a role and why and how they influence investment decision making. We have drawn the following diagram to represent this model.

According to the model, and as shown in the diagram above, investment decision making must be considered, from a dynamic perspective, not as a point in time but as the result of a decision-making process. This process is influenced by (1) organizational and external contexts along any number of points that surround it, (2) actors involved, and (3) characteristics of the investment and of the investment decision to be made. Among investment characteristics, strategic character is a key factor influencing decision making. But strategic character is not given; it is interpreted by actorsFootnote 3 and by organizations, due to the action of several filters. These elements influencing investment decision making are described in more detail in the following pages.

Decision-making: not a point in time but a process

A decision is a step in a decision-making process, defined as a dynamic chain of actions and events. When it can be identified,Footnote 4 a decision cannot be considered as a single element or as a point in time.Footnote 5 The decision-making process comprises three phases: identification (diagnosis), development (build-up of solutions), and selection (evaluation of the different solutions and choices). At the very beginning of the decision-making process, the diagnostic phase is crucial in two ways: Firstly, it translates—or not—an initial idea (Desreumaux and Romelaer 2001) into a decision event; secondly, it influences the subsequent phases of development and choice. For the sake of clarity, the preceding diagram represents the decision-making process as smooth and linear, which is rarely the case: In the real world, the decision-making process is generally cyclical and uneven, with feedback loops, pauses, and dead ends. It is only linear and sequential in the case of highly structured decisions, based on ready-made solutions (Desreumaux and Romelaer 2001).

Decision-making: a process influenced by organizational and external contexts

Organizational context and external context influence all of the decision-making process phases. Organizational context comprises structure, strategy, and culture; the external context is referring to the organization’s environment. Main external context components are competition moves, demand, social evolutions, regulation, the general economy, and technological progress. However, an organization’s environment is not given; rather, it is interpreted and “built” by actors’ vision and by organizational filters (corporate culture, routines, control systems). As described by Lyles ((1987), p 266), with reference to Weick (1979), “organizations will invent the environment to which they will respond by deciding which aspects of the environment are important or unimportant.”

Decision making: a process influenced by actors’ power

The actors involved influence the course of the decision-making process and its result, which can be a negative, positive, or no-decision. Decision making is political because organizations are political systems, i.e., they are collectives of people with competing interests. In any organization, a dominant coalition (Prahalad and Bettis 1986), or a “key collection of individuals” composing top management, has a significant influence on the way a firm is managed. According to Miller et al. (1996), the dominant coalition is a “core triad of heavyweight functions”: production (or its equivalent in services companies), marketing and sales, and finance. Heavyweight functions are closely associated with core business. Together with general management, this coalition imposes its choices upon the organization because, “simply put, decisions follow the desires and subsequent choices of the most powerful people” (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki 1992: 23).

Decision-making: a process influenced by investment characteristics

Any decision-making process is inserted into an “interwoven streams of issues networks” (Langley et al. 1995); concurrent decision processes within the same organization may be interrelated because they share the same resources but also simply because “they bathe within the same organizational context, involving the same people, the same structural design, the same strategies, and the same organizational culture and traditions” (Langley et al. 1995: 273).

Dutton et al. (1989) empirical study has also shown how relationships, or “linkages,” among issues are an element which strongly influences decisions in organizations. Figure 2 below illustrates these interwoven streams of issues and how decisions (the arrows in the figure below) happen to come out of the decision-making flow.

Organizational decision making as interwoven, driven by linkages (Langley et al. 1995: 275)

In every organization, there is some competition between (streams of) issues, for financial and human (the time and energy of powerful managers) resources (Langley et al. 1995) and investment projects which compete against each other (Ross 1986).

Characteristics of investment projects do influence the outcome of this organizational competition.Footnote 6 Investment characteristics are numerous and diverse. Examples of characteristics are: investments importance to the organization; their complexity, and the level of organizational change they would entail; the number of actors involved and the stimuli evoking them (threat or opportunity, level of urgency); the available solutions (ad hoc or ready-made, internal or external). Investments can also be categorized according to their functional object (production, human resources, etc.) or according to their strategic character or nature.

Research findings demonstrate that strategic character of investment issues play an important role in the competition for resources. Several streams of decision-making research (strategic process research, organizational finance, and cost accounting) have mentioned the importance of strategic character of investment issues in decision making. Some research mentions the quest for competitive advantage as a driver of investment decision making (Burcher and Lee 2000; Chen 1995; De Bodt and Bouquin 2001; Putterill et al. 1996). Others note the decisional importance of factors such as the link between investment decisions and a company’s strategic goals (Alkaraan and Northcott 2006; Carr and Tomkins 1996; Maritan 2001; Segelod 1997; Van Cauwenbergh et al. 1996) or the investment impact on product quality and competitive position (Butler et al. 1991). These findings meet those of the “alternative” literature on energy-efficiency investments, where the (absence of a) link between energy-efficiency investments and a company’s core business is often mentioned as a (negative) factor which plays an important role in the decision-making surrounding investments (de Groot et al. 2001; Harris et al. 2000; Parker et al. 2000; Sæle et al. 2005; Sandberg and Söderström 2003; Sardianou 2008; Sorrell et al. 2000; Velthuijsen 1993; Weber 2000, 1997).Footnote 7

Yet, investments are not (only) strategic for objective reasons. They are interpreted as such by decision makers and organizations, as are all data and decision events. At the beginning of the decision-making process, issue diagnosis assesses and categorizes new data and events, which are interpreted—“infused with meaning” (Dutton and Jackson 1987)—at the individual and organizational levels. During this process, some issues become “decision events” (Dutton et al. 1983). But, during the issue diagnosis process, information is distorted by the use of heuristics—rules of thumb, shortcuts, routines, which decision-makers use to simplify complex problems—and by cognitive biases, these “hidden decision’s traps” (Hammond et al. 2001) common to all individuals. The influence of heuristics and cognitive biases always distorts information in the same way: Managers unconsciously search for information supporting views, beliefs, or hypotheses that they have long cherished (Makridakis, in Mintzberg et al. 2005: 168). Moreover, managers’ personal pre-existing knowledge systems act as filtersFootnote 8 of organizational events. The organizational context also influences how decision makers understand and interpret issues. The meaning attributed to the same event, and the type of reaction to this event, will therefore be different from one organization to another. The same kind of investment will be perceived as more or less strategic by different decision makers and organizations.

But, beyond these differences in perceptions or interpretations, how can we define the strategic character of an investment? Strategic process research has highlighted the relation between the strategic character of an investment project and the characteristics of the decision to be made, and has studied how these characteristics influence the decision-making process. Strategic decisions are described as important, with a high impact on the organization’s performance or survival, as uncertain and highly unstructured decisions.Footnote 9 The more unstructured the decision to be made, the higher the number of actors involved in the decision-making process (Butler 1990; Cyert and March 1963; Thompson 1967; Hickson et al. 1986). The higher the number of actors involved, the more politicized (Miller, et al. 1996),Footnote 10 longer, sporadic, and cycling the decision-making process (Desreumaux and Romelaer 2001; Hickson et al. 1986). In fact, we observe that strategic process research describes and theorizes strategic investment decisions but does not investigate what is that makes an investment strategic or, in other words, what is that makes the strategic character of an investment. Actually, we could not find any satisfyingFootnote 11 definition of what “strategic” means in the strategic decision-making literature.

The model of investment decision making briefly described above is based on literature review and theoretical exploration of the academic field of decision making. Most parts of the model have been studied and supported by theoretical and empirical research. Our contribution is twofold; firstly, it lies in the assembling of various research streams into one coherent and integrated model of investment decision making; secondly, and this is the focus of this paper, we have investigated how investment strategic character influences investment decision making. In order to do so, we have completed the theoretical framework defining strategic character, which is described in the next section.

Strategicity

Most strategic decisions are investment decisions because strategic decisions generally translate into resource allocations.Footnote 12 Additionally, decision-making research has shown that strategic character of investment decisions matters, but just what does the expression “strategic character” cover?

Dutton et al. (1989), in their seminal paper on the dimensions of strategic issues,Footnote 13 provide a useful categorization in this regard. Having defined strategic issues as “events, developments or trends that are perceived by decision-makers as having the potential to affect their organization’s performance” (Dutton et al. 1989: 380), they differentiate between analytic issue characteristics and issue content characteristics. They define analytic characteristics as characteristics “which can be used to order issues in their relation to one another (e.g., by their duration, by their impact, by their interconnectedness) … [whereas] content dimensions describe classifications into discrete groups” (Dutton et al. 1989: 381).Footnote 14 Examples of issues analytic characteristicsFootnote 15 are the magnitude and implications of their impact on an organization, their certainty, novelty, time pressure, and causal relationships, whereas issue content characteristicsFootnote 16 concern the organization’s mission and role, its resources, its environment, its businesses, and its relationships with outside entities (Dutton et al. 1989: 389). This categorization is useful to develop a conceptual framework for strategic investment decisions.

As already mentioned (see end of previous section), strategy process literature has mainly studied analytic characteristics of strategic investment decisions, without making reference to the content characteristics of investment projects. Therefore, in strategy process research, decisions are defined as “strategic” based on their analytic characteristics only: Decisions are strategic because of their high potential impact on the organization or because they are highly uncertain or unstructured. However, to define the strategic nature of a decision simply by saying that it is important and unstructured seems insufficient to identify and analyze strategic investment decisions.

Strategic nature must also be analyzed according to investment content. As expressed by Maritan and Schendel (1997: 262): “how can we really understand the process of making strategic decisions without explicitly considering the strategy content of the decisions and how it links to outcome? To see the decision process and content as separable is wrong.” Indeed, Maritan (2001), in her study of 29 investment decisions in a large pulp and paper company, has shown that investment content does influence decisions in four ways: Firstly, it influences the hierarchical level in which the project is handled; secondly, it influences the hierarchical level of its “champion”; thirdly, investment content influences the mode of approval of the project (more or less formal or informal); fourthly, content influences the level of procedural rationality.Footnote 17 The Dutton et al. 1989 empirical study also demonstrates the importance of content characteristics compared with analytic characteristics. Issue content characteristics are mentioned almost as often by the decision makers interviewed. Content characteristics most influential in decision making are those related to an organization’s mission and role, its resources, its businesses, and its relationships with outside entities (Dutton et al. 1989). In fact, content characteristics seem connected with factors we have identified in our literature review as influencing investment decision making, i.e., the factors “link [of an investment project] with a company’s strategic goals” and “quest for competitive advantage” (see first paragraph, p. 7). However, to define the strategic nature of an investment by saying that its content is related to organization’s mission and role, to its strategic goals, quest for competitive advantage, or businesses, seems, again, rather vague.

Therefore, on the whole, definitions provided by the different streams of decision-making research are not precise or comprehensive enough to qualify an investment strategic character. To evaluate the strategic character of investment decisions, we need to examine investment content and analyze how it enables an organization to strengthen its strategic position. To conduct this analysis, we have to draw from the concepts of another vast research field in strategy, the field of “strategy content.” An important field of business management, “strategy content” literature offers definitions of strategy and solutions to make the best strategic choices.

Strategy ultimately consists of creating a durable competitive advantage.Footnote 18 Accordingly, we can consider that the main constituent of the “strategic character of an investment” is this investment’s contribution to a firm’s competitiveness. Investment content determines investment contribution to core business and to an organization’s competitive advantage. Therefore, strategic character depends on investment content. Based on this reasoning, we will use the following definition: An investment is “strategic if it contributes to create, maintain or develop a sustainable competitive advantage” (Cooremans 2011).Footnote 19

This definition implies, firstly, that an investment, or an investment decision, is not simply strategic or non-strategic, contrary to what it is generally (implicitly) described by the decision-making literature. Strategic decision making is a continuum, where decisions can range anywhere from non-strategic to wholly strategic. The more strategic an investment is, or in other words, the more it contributes to competitive advantage, the more important it is to a firm’s performance or even survival. We suggest the word “strategicity” to express and describe the strategic character—or strategic nature—of an investment.

This definition implies, secondly, that the main constituent of the “strategic character of an investment” is this investment’s impact on a firm’s competitiveness. What are the indicators which allow measurement of competitive advantage generated by a strategic decision?

According to Michael Porter, “competitive advantage grows fundamentally out of value a firm is able to create for its buyers that exceeds the firm’s cost of creating it” (Porter 1985: 3). Value is what buyers are willing to pay for what a firm provides them and is measured by total revenue. Two theoretical approaches have defined the means to build superior value at a lower cost: the “activities approach” (leaded by Michael Porter) and the “strategic resources approach.” The first approach is centered on the concept of activities which are “the basic units of competitive advantage.” The second theoretical approach is based on the concept of strategic resources which, according to the Resource Based View (RBV) (on strategy), are the founding elements of competitive advantage. These two approaches agree on a bi-dimensional concept of competitive advantage. These two dimensions are, on one hand, value (which a firm is able to create for its customers) and on the other hand, cost (of creating this value). The two approaches to competitive advantage only differ in the means of developing superior value and reducing costs: choice of activities for one and resources development for the other.

However, an analysis of several theoretical frameworks—strategic risk, resource dependence (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) and RBV—leads to propose taking risk as a third dimension of competitive advantage, supplementing the value and costs dimensions (Cooremans 2011 Footnote 20). Therefore, we suggest enlarging the definition of competitive advantage by saying that competitive advantage is a three-dimensional concept, formed of three interrelated constituents: costs, value, and risks. We have designed the figure on the next page to very simply illustrate the three dimensions of competitive advantage:

Using the theoretical framework described above, we can explain why strategicity is an important driver of investment decision making as follows: A decision-making process only starts if the new decision event, the “initial idea” (Desreumaux and Romelaer 2001) is interpreted, in the diagnostic phase, as a stimulus important enough to trigger action (Mintzberg et al. 1976); however, crossing the action threshold is not enough to ensure a positive decision because of the organizational competition existing between streams of issues or projects (Langley et al. 1995; Ross 1986). An investment project perceived and categorized as non-strategic will most probably lose the competition and will be excluded from the decisional stream, to end up as a no-decision; a category little studied (Bachrach and Baratz 1962). It may also result in a negative decision. However, the highly strategic nature of an investment may also complicate and slow down the decision-making process because of the novelty and complexity it implies. In summary, the strategic nature of an investment project is an important and necessary condition but not always sufficient to automatically entail a positive decision.

Empirical research

As shown in the previous section, the influence of investment characteristics—and, in particular, of investment strategic character—on investment decisions has been demonstrated by a large amount of research. Yet, the modalities of this influence need to be better understood and described. This was the goal of our empirical study. Based on the theoretical framework described above, this study was conducted in Geneva, Switzerland, from 2006 to 2007.

Data collection

The research was undertaken in collaboration with the University of Geneva Business School (HEC) and the Geneva Energy Office (ScanE) and is based on interviews and questionnaires submitted to major electricity consumers of the Geneva canton (sites consuming more than 1 GWh of electricity per year), participating in a peak demand-side management program. Thirty-five companies supervising 61 buildings or industrial sites participated in the survey, 19 of which are active in the secondary sector (metalworking, clock- and watch-making, chemical and pharmaceutical industries) and the rest of which are active in the tertiary sector (chain stores, parking lots, shopping malls, conference/exhibition centers).

Data collection consisted of a two-step survey: (1) On the occasion of a semi-directive interview with the company manager responsible for energy issues (usually the facility or technical manager), a questionnaire is filled in; (2) A subsequent questionnaire was completed by a top finance manager. Some questions were identical to those of the first questionnaire in order to check for different views on the same issues between managers in charge of energy and finance managers. Only 18 “finance questionnaires” have been collected (11 secondary sector and seven tertiary sector companies; 14 of these companies are medium to big, with more than 250 employees). Although the sample size is small, data collected give interesting indications on businesses’ general investment behavior and on energy-efficiency investment behavior. They also enable a comparison with the De Bodt and Bouquin (2001) survey (44 usable questionnaires, out of the thousand sent out by mail), from which most of the questions regarding general investment behavior were taken.

Strategicity measurement

According to our definition, the more an investment decision contributes to competitive advantage, the more strategic it is. Thus, to measure strategic character (or “strategicity”) of an investment, one has to measure its contribution to competitive advantage in each dimension: value, costs, and risk. To estimate the strategic character of energy-efficiency investment to the companies of the sample, we asked managers (finance managers and energy managers) to estimate the impact of the adoption of energy-efficient technologies on their company, in terms of risks, costs, and value. The following question was submitted to energy and finance managers:

Respondents were asked to give a value from 1 to 5Footnote 21 to each of the constituents—risks, costs, and value—analyzed by questions 2–5. By aggregating the answers, a scale of interval was built, allowing measurement of the strategic dimension of an energy-efficiency investment, which is thus spread out from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 15.

Results and discussion

General investment behavior

Results concerning the relative importance of the financial and strategic logic in investment choices and businesses’ general investment behavior will be discussed in this section. In this respect, the most important conclusions are the following: (1) profitability plays an important but not decisive role in investment decision making; (2) the diagnostic phase is crucial; (3) there is competition between investment projects; (4) investment projects which are considered as more strategic win the competition. Another important finding of our research is unorthodox practices of businesses in investment choices. These various points will be discussed in the following pages.

According to the mainstream approach on investment decision-making, an investment is decided according to its profitability. Three capital budgeting tools proposed by capital investment theory are most often used to assess an investment’s profitabilityFootnote 22: payback period, Net Present Value (NPV), and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) methods. These methods specify the modalities fixing the discount rate and take into account the risk attached to an investment project.

Our research results help confirm that investment profitability plays an important role in decision making, as shown by various questionnaire responses: Profitability analysis is mandatory for an investment project, irrespective of its category, for an overwhelming majority of companies.Footnote 23 Three quarters of the financial managers disagree with the assertion that “financial evaluation of the investments has, after all, a small influence on the final decision”. Profitability calculations are considered as “decisive” in the choices made by a quarter of the respondents (28 %) and as “important” by 50 % of the respondents.

However, the influence of profitability on investment decision making is far from being exclusive. As admitted by the quasi-totality of financial managers who respondedFootnote 24 the “profitability of an investment is not sufficient to entail a positive decision.” A majority of financial managersFootnote 25 confirm, on the other hand, that “a project can be realized even if it is not profitable.” These results are similar to those of previous research, in particular, that of De Bodt and Bouquin (2001).

The influence of profitability on investment decision making is even secondary, as demonstrated by our research, because of the influence of the three following factors: (1) power relationships between company departments influence the investment processFootnote 26; (2) investment amount and category determine the procedure, the analytic and capital budgeting tools used, profitability requirements, and the different steps a project has to follow; investment category appears to influence also the type of financing (self-financing or borrowing); (3) strategic investments have more chances of being selected.

Issue diagnosis plays an important role in the decision-making process and therefore in investment choices. Two elements in companies’ answers show its importance. First, investment projects result more often from opportunities perceived at the operational level than they result from a systematic search for a relationship with a company’s goals; this implies an open decision-making process in the beginning. Second, in the majority of cases, budgets were not defined in advance but only after identification of investment opportunities. A formal procedure of investment control exists in a large majority of companies (approximately four out of five). Investment amount influences this procedure in the majority of the companies questioned,Footnote 27 as well as the stages that the investment project proposal has to follow.Footnote 28

Investment categorization plays a crucial role in this formal procedure. Almost all companies classify investment projects according to a pre-existing typology. The category chosen subsequently influences the type of analysis applied to an investment project (such as analyses of profitability and risk, or commercial, technical, legal, and ecological analyses) and the financial methods used to assess its profitability.Footnote 29 The investment category also influences the stages that a project has to follow in 44 % of companies.Footnote 30 Table 1 below summarizes these results:

The Table 2 on the next page shows investment categories chosen by financial managers as being the closest to the investment categories used in their company. “Investments to maintain or renew existing production capacities” is the category recognized by the largest number of companies.Footnote 31 The second investment category chosen (72 % of Geneva respondents) is the category “investments to increase productivity of existing means of production.” Thus, the categories most frequently used by companies are categories related to core business.

Categorization of investment projects by companies and its huge influence on the decision-making process and therefore on investment choices, provides explanatory value to another important aspect of our theoretical model: the existence of competition between investments.Footnote 32 This element is also confirmed by the fact that the “existence of other more important investments” is considered as the first barrier to energy-efficiency investments by the financial managers in our survey, as well as by companies in the De Groot et al. (2001) survey. De Groot et al. do not specify what these “more important investments” are. They simply note that “the most important barrier for firms is the existence of other investment opportunities that are considered more promising or important, or… more attractive” (De Groot et al. 2001: 726). But they indicate elsewhere that “energy saving is just one of the criteria on which a new technology is judged and that there are other complementary benefits such as increased capacity and improved product quality that are considered along with energy saving” (idem: 723).

Although we did not systematically collect information about what respondents in our survey meant by “more important investments,” some respondents responsible for energy management mentioned during the interview that more important investments were “investments to obtain certifications, or investments in production” (company no. 26, steel industry), “investments in means of production” (company no. 29, steel industry), “investments in means of production or to develop new selling points” (company no. 32, watchmaker), “investments in machines” (company no. 33, watchmaker). These descriptions also correspond to the investment categories indicated as the most frequently used by companies (as described in the table above). We can therefore consider that “more important investments” are those which are directly linked with a company’s core business: in other words, those which are strategic investments. Therefore, another central point of our theoretical framework gains explanatory value, which states that strategic investmentsFootnote 33 have more chance to win the organizational competition existing between investment projects. This is also supported by the fact that, in our research, 16 financial managers out of 17 agreed with the assertion: “Above all, a project must contribute to the realization of the company’s strategic goals” (40 companies out of 44 in the De Bodt and Bouquin survey, 2001).

Thus, strategic character appears as being more important than profitability in investment choices, at least for companies’ financial managers. This would explain why companies do not adopt certain technological advances, even when they consider them profitable, as is the case for the companies questioned by De Groot et al. (2001)Footnote 34 and by capital-rationing firms surveyed by Ross (1986). This may also explain why unprofitable investments may be chosen, as indicated by a majority of financial managers in our Geneva survey.Footnote 35

Another interesting issue regarding general investment behavior is brought into evidence by our research: a lack of conformity of investment practices with capital investment theory prescriptions. Indeed, results show unorthodox behavior by companies in our survey, regarding the capital budgeting methods used.Footnote 36 The following aspects in particular must be noted:

-

Discount rate. Only 60 % of the companies surveyed fix the discount rate by basing it on the cost of shareholders’ equity and the cost of loan (weighted average cost of capital). Fifteen percent of companies fix the discount rate in a fixed way. Risk is taken into account in discount rate setting in less than one company out of five.

-

Time value of money. Three quarters of the companies surveyed use a dynamic method to assess profitability (NPV or IRR) and the simple pay-back method at the same time. Some companies, however, (at least two) use only the pay-back method and with a long duration of 5 to 6 years.

-

Risk. Project risk analysis is compulsory for only 40 % of companies surveyed.Footnote 37

-

Time horizon. Strong pressure in the short-term is indicated by several respondents in the interviews. As expressed in a rather emblematic way by the general manager of the Geneva subsidiary of an American company (company no. 30, coverage of ceramic surfaces with metallic powders alloys; total energy costs in Geneva = 8 % of the turnover, electricity costs = 4 % of turnover), “1 year [to get back the initial investment capital], we get the money at once, 2 years we need to fight, 3 years, we never get it. ‘Waiting’ is a forbidden word in our company.”Footnote 38 Under these conditions, numerous opportunities for attractive investments are eliminated.

-

Outside financing and leverage. The large majority of companies in our sample are self-financed and are uninterested by a loan, even at a reduced rate of interest, thus giving up the advantages of financial leverage. The same result was also found by a survey of International Finance Corporation (IFC) (2006) on Russian companies’ practices regarding investments in energy efficiency: “More than 60 % of companies believe that insufficient funds is the key obstacle hampering energy efficiency projects… However… only every fourth company has applied for outside financing”Footnote 39 (IFC, 2006: 34). Discussing these findings, ICF notes that “it is curious that over one-third of those who did not apply for loans due to ”sufficient funds“ also mentioned problems related to insufficient financial resources for energy efficiency” (idem, p. 35). IFC explains these findings by the fact that many companies do not understand the advantages of financial leverage. Based on our theoretical framework, our explanation would be that it is because these investments are not considered as strategic, so that internal financial resources are not granted and outside financing is not considered an option. For example, the person in charge of energy in company no. 33 (watchmaker) mentioned that the company borrows to purchase production equipment, but that, regarding investments for operations, the rule is self-financing.

Based on our findings, we can conclude that the way a project is categorized influences the procedure and the profitability assessment method, as well as profitability requirements and financing. In the context of projects categorization and of competition between projects, and beyond questions regarding businesses’ unorthodox financial practices, the strategic character of investment projects appears as the primary driver of investment choices, while investment profitability appears as a generally necessary but insufficient condition. The answers of the Geneva managers hereby support the findings of previous studies regarding the respective influences of financial and strategic aspects of investment projects, as well as the validity of our model of investment decision making.Footnote 40

Since strategic character is the main driver of investment decision making, it is important to assess how strategically energy-efficiency investments are perceived by businesses. The next section will discuss this point.

Energy-efficiency investments behavior

Strategic character of energy-efficiency investments

Energy-efficiency investments exist as a category for almost half of the 18 companies which responded to our questionnaire, in a similar proportion in the tertiary and secondary sectors. Indeed, the category “Investments intended to reduce energy consumption”Footnote 41 was selected by 53 % of companies.Footnote 42 It is the third most frequently mentioned category (along with the categories “Investments for production process improvement,” “For machinery & equipment legal conformity,” and “Replacement”).

The fact that energy-efficiency investments do—or do not—exist as a category in companies has never been discussed in the energy-efficiency literature. Actually, the issue of investment categorization, in spite of its consequences on investment choices, has been almost completely left out of the general investment literature as well, probably because there has been no need to look for any special treatment applied to a category in particular.

How strategically are energy-efficiency investments considered? This is an important question since strategic character is an essential condition for an investment project to be chosen. If energy-efficiency investments are perceived as non-strategic, their chances of being chosen will be rather low.

According to our definition, the more an investment contributes to create or to strengthen a company’s competitive advantage, the more strategic it is. Competitive advantage is a three-dimensional concept, composed of three interrelated constituents: costs, value, and risks (as represented by Fig. 3 on the next page). Based on the measurement tool described in the methodology section (see p. 11–12), energy and finance managers were asked to rate—from 1 to 5—the contribution of energy-efficiency investments to decreasing risks, decreasing costs, and increasing product value in their company.

Three main themes emerge from our empirical research. First, energy-efficiency investments are perceived as non- to moderately strategic by our respondents. Second, of the three variables which compose the strategic character of an investment, the variable “Costs” is considered most important.Footnote 43 Third, arithmetic hides a large variety of answers, both between companies (including companies operating in the same business sector) and within companies (between managers of the energy and finance functions). Let us further examine these three themes.

First, on average, energy-efficiency investments are considered “not strategic” to “moderately strategic” for the company by questionnaire respondents. Figure 4 on page 18 shows how managers assess energy-efficiency contribution to the three constituents of competitive advantage. Energy managers’ and finance managers’ results are presented on the left and right sides of the figure, respectively. The average score is 9.1 out of 15 for energy managersFootnote 44 and 8.6 out of 15 for finance managers.Footnote 45 If we divide by 3 to reduce these figures from 15 to 5, we obtain scores of 3 out of 5 for energy managers and 2.9 out of 5 for financial managers. Based on these results and according to the measurement scale definedFootnote 46 (see also the methodology section, p. 12), we can conclude that energy-efficiency investments are considered as “not important” to “moderately important” by the respondent managers.

The dispersion of the answers between the two groups (energy and finance managers) for the three variables (risks, costs, and value) presents significant differences. About 50 % of the energy managers consider that adopting energy-efficient technology is in no way important to risk reduction, while the modal choice is the inverse for finance managers: nearly half of them consider the adoption of this technology as moderately important to very important to risk reduction. For finance managers as well as for energy managers, “risk” means “price risk,” i.e., future price increase or price instability. Energy outages are perceived as a minor risk by companies, only a small minority of which are equipped with a backup system to produce electricity in case of a grid breakdown.Footnote 47

The non- to moderately strategic character of energy-efficiency investments for managers in our research is supported by two additional results. On one hand, the contribution of these investments to improving their company’s competitive position is considered as not important by energy managers as well as for finance managers.Footnote 48 On the other hand, the importance of these investments for the corporate image (corporate image is a strategic resource in strategic management literature) is estimated as moderately important by energy managers and as of rather low importance by finance managersFootnote 49.

The second striking conclusion is the fact that, out of the three dimensions which compose the strategic character of an investment, it is the constituent “Costs” which is considered as the most important.Footnote 50 This is the case for all respondents (energy and finance managers) and for all industries.

The prospect of energy costs reduction is, however, not as stimulating as one might believe; indeed, in the De Groot et al. (2001) study, the fact that energy costs are not important enough was the third factor blocking the adoption of energy-efficient technology. This answer is especially interesting because companies questioned by De Groot et al. (2001) were active in energy-intensive industriesFootnote 51 and had energy costs amounting to a rather high percentage of their turnover (approximately 10 %). If energy costs are considered not important by managers, the perspective of an energy costs reduction is not a very powerful factor in motivating them toward investing in energy-efficient technology. Thus, energy cost-reduction is a stimulating factor, but not always sufficient to entail positive decisions regarding energy-efficiency investments.

Again, the importance of the strategic character of an investment provides explanatory power of corporate investment choices, as these results show that energy costs must not be interpreted according to a financial approach but according to a strategic approach. For certain companies confronted with competition for prices and low costs, such as the machinery or metals industries, low costs are a strategic necessity of competitiveness and thus, of survival. This is the situation faced by companies, nos. 23 and 25, in our sample, as illustrated by a statement from the energy manager of company no. 25 (machinery industry): “we constantly fight to make as well [in terms of quality] as the Japanese, at lower costs.” However, for most companies, the cost dimension is not a priority in energy-efficiency investments decision-making. For these companies, energy costs are considered a somewhat necessary evil.

The third important conclusion of our findings regarding the strategic character of energy-efficiency investments is the variety of interpretations, which is observed. Variance of the answers between managers of the same groups is extremely highFootnote 52 as well as variance between companies, even within the same industry (as shown in details in Table 3 of the Appendix). Generally speaking, investments in energy efficiency obtain a higher score in the three dimensions of competitive advantage (“risks,” “costs,” and “value”) with managers of the tertiary sector than with those of the secondary sector.

Yet, as a general finding of our empirical research, we can state that energy-efficiency investments are considered at best, on average, as moderately important by respondent managers.

Energy-efficiency investment behavior

According to our theoretical framework, non-strategic investments lose the competition for human and financial resources which exists within each company. Therefore, the low strategic character of energy-efficiency investments should have negative consequences. This is supported by our findings, as described in this section.

Two questions, F-9-16Footnote 53 and F-10-6,Footnote 54 in particular, aimed at highlighting differences in the treatment between general investments and energy-efficiency investments. Question F-9-16 investigates the time horizon used by companies to assess investment profitability (all investment categories; several answers possible). Among companies which responded to this question, 72 % declare taking the life span of equipment as the forecasting horizon for their profitability assessment and almost 40 % mention the strategic horizon of the project as the time horizon for their profitability assessment.Footnote 55 According to these answers, investment duration for energy-efficiency equipment should therefore last about 15 to 20 years.Footnote 56

Yet, profitability horizons for energy-efficiency investments indicated by the 18 companies (having responded to question F-10-6)Footnote 57 are much shorter: 2 years (two companies), 3 to 5 years (four companies), and 10 years (two companies). Therefore, companies’ practices regarding energy-efficiency investments contradict their answers regarding general investments.

These findings can be interpreted as proof of a different and unfavorable treatment applied against energy-efficiency investments. This interpretation is supported by a statement given by the energy manager of company no. 31 (Swiss company, electronics industry), who, during the interview, mentioned a duration of 3 years for investments in energy efficiency but a duration of 10 years for “production tool” investments. Thus, companies would allow longer durations for investments in the production tool. This would explain why, although companies indicate life span of equipment as the basis for investment duration, energy-efficiency investment duration is often much shorter.

This would also be further proof of the role played by strategic character in investment choices: investments in production tool are generally considered highly strategic, i.e., significantly contributing to core business.Footnote 58 Therefore, they would benefit from less stringent selection methods and easier access to capital.

Conclusion

Investment categorization exists in an overwhelming majority of companies. Categorization strongly influences investment control procedure, profitability assessment methods, profitability requirements, investment financing, and, ultimately, investment choices.

In the context of project categorization and of competition between projects, the strategic character of investment projects appears as the primary driver of investment choices. When an investment is perceived as important for core business, access to financial resources is easier. We can interpret in this way the fact that budgetary constraints come in only at eighth position as a hindering factor to energy-efficiency investments for the Dutch companies questioned by, de Groot et al. 2001.Footnote 59

Diversity in companies’ investment (general and energy efficiency) behavior is another important finding of our research. Diversity is observed in all the aspects analyzed by our research: investment control procedures (methods of analysis and of profitability assessment, fixation of the discount rate, investment duration), energy-efficiency investment behavior, and perceptions of energy-efficiency investments’ strategic character. This diversity is noticeable even between companies active in the same business sector and which present the same characteristics (as shown in Table 4 of the Appendix).

More research is needed to explain the diversity observed in firms’ investment behavior as well as to better understand the modalities and consequences of project categorization in investment choices. The influence of investments’ strategic character on investment duration, discount rate applied, and financing, especially, has to be further investigated. Still, our results are coherent with the new model of decision making that we propose, as well as with previous research in the fields of decision making and of energy-efficiency investments.

Regarding energy-efficiency investments, more research is also needed, which could take any or all of the following four directions: (1) a large number of companies should be surveyed in order to know if they use the energy-efficiency investment category (our sample size was only 18 companies). This could be done in different countries, to look for possible cultural differences, and by using a dynamic method to look for changes over time. (2) When energy-efficiency investments do exist as a category, research should look at what the selection methods are and if they are more stringent than those applied to other investment categories. (3) When energy-efficiency investments do not exist as a category, how energy efficiency is taken into account by companies in their decision-making processes of investments not directly concerned with energy use or consumption (but which have an impact on it). (4) What happens when an energy-efficiency project cannot be categorized at the beginning of the decision-making process because this investment category does not exist; in other words, what are the consequences of a non-categorization on the important step of issue diagnosis, at the beginning of decision-making process. Our hypothesis regarding this last point is that non-categorization entails slowing of the decision-making process, or prevents it from starting at all (a situation which would contribute to explaining why energy audits sometimes never translate into investment projects).

If we apply our decision-making modelFootnote 60 to energy-efficiency investments, taking the case of a company considering energy as a low strategic issue, the following reasoning can be developed, based on our empirical results:

-

Organizational context. Corporate culture regarding energy and energy efficiency is low, and the company’s dominant logic does not consider energy issues as strategic issues. Therefore, the company does not effectively manage energy use; it simply uses energy (Tunnessen 2004). With no energy management, energy is invisible not only in physical terms but also in managerial terms.

-

Investment characteristics. An energy-efficiency investment project is [perceived as] not or weakly strategic. Whether opportunity or threat, stimulus to this investment is weak. Positive impact on the company is perceived as being low (or impact may even be potentially negative as, for instance, in case of a production line disruption due to the installation of new less energy-consuming equipment). Still, the project may be unstructured (without any pre-existing solution, technological/organizational/financial solutions must be developed, internally or with help of external experts) and uncertain (regarding its physical and financial savings).

-

Actors. The investment project being categorized as non-strategic; upper management is neither involved nor interested (Maritan 2001).Footnote 61 The project is championed, at the level of the technical or facility management department, by a low power manager. This manager most probably does not master finance, strategy, or marketing; the essential tools needed to “sell” investment projects to upper management.

-

Decision-making process. As diagnosis is unfavorable, low resources are allocated to information research and to the building of solutions.Footnote 62 A priori rules or routines (DeCanio 1993; Stern and Aronson 1984)Footnote 63 impose very stringent selection criteria regarding investment duration or discount rate, more stringent that those which would apply to strategic investments. Even if showing a fair—or even high—return, the energy-efficiency investment project is rejected during the selection phase. Sometimes no decision is made at all.

These elements are synthesized in Fig. 5 above:

It appears from our conceptual framework and empirical research that strategicity is more influential than profitability in corporate investment choices. Investment profitability appears as a generally necessary but insufficient condition. Unfavorable diagnosis regarding strategicity entails several negative consequences, the most important being that upper management is not interested and that more stringent selection criteria—or routines—apply to non- or low strategic investments.

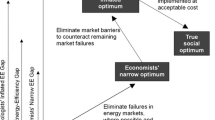

Energy-efficiency investments, when they do exist as an investment category, are perceived as weakly strategic by companies. This would explain why many energy-efficiency projects, although highly profitable, remain unchosen. Our findings lead us to propose an explanation of the energy-efficiency gap different from the mainstream one, by redesigning the market barrier concept. This is represented by the diagram in Fig. 6 on the next page.

As shown in the diagram, there are four levels of organizational barriers to energy-efficiency investments, each of them influencing the levels below. We have labeled the four barrier levels “Base,” “Symptom,” “Real,” and “Hidden.” The first two levels are the barriers usually described in the energy-efficiency investment literature as being responsible for the energy-efficiency gap. We add two levels above the first ones, to better describe the obstacles faced by energy-efficiency investments. These upper levels constitute meta-barriers, a framework in which the other barriers can be described (Eyre 1997), which determine energy use, routines and decisions, or non-decisions, within firms regarding energy-efficiency investments.

‘Base’ barrier

First-level barrier concerns information, or rather, the lack of knowledge regarding energy-efficiency measures, as well as regarding their technical and financial aspects. Lack of knowledge is a general problem in firms without energy management, but it may also be a problem in firms which do manage energy where it arises from the complexity of energy-efficiency measures, at least in very large buildings, which requires multidisciplinary skills. Although this is an important barrier, it is not sufficient to explain firms’ negative decisions regarding energy-efficiency investments.

‘Symptom’ barriers

These are designated as such because they express signs of deeper, invisible problems, or of mistaken interpretations. For instance, capital is not lacking but is allocated to other investments; risk is said to be high, when in fact it is not even assessed.Footnote 64 Hidden costs, which are commonly said to lower energy-efficiency investments profitability, are an easy explanation, especially since they cannot, by definition, be assessed in precise figures.

‘Real’ barrier

The third level is the invisible problem at the source of second-level symptoms. It is the real obstacle to energy-efficiency investments: Their non- or low strategic character for companies, which consider energy or energy use neither as a contributor to their competitive advantage nor as a critical resource, for the risks to the security of energy supply are ignored. Indirect benefits of energy management, which can in many cases increase strategicity, are poorly understood or included in investment assessments.

‘Hidden’ barrier

The fourth level comprises the various cultural influences which drive organizations and their decision makers to consider energy-efficiency investments as weakly strategic, beyond possible objective reasons. It is “hidden” because it influences an organizations’ behavior and investment choices in a subconscious way.

A clear implication of our findings and of the conceptual framework presented in this paper is the following: In order to successfully champion energy-efficiency investments, all energy-efficiency actors—scholars, practitioners, and public programmers—need to highlight, as much as possible, the strategic character of energy-efficiency investments. In other words, they need to highlight, whenever it is possible, the impact of energy-efficiency investments on firms’ competitive advantage in performing their core business.

Notes

Where net present value is calculated with a hurdle rate higher than the cost of capital for a company.

“General” here meaning not especially aimed at energy conservation.

In the field of organization behavior, “actors” mean individuals and groups.

It is not always possible to trace decisions retroactively. “If a decision is like a wave breaking over the shore—that is, perhaps identifiable at some sort of climax—then tracing a decision process back into an organization becomes much like tracing the origin of a wave back into the ocean.” (Langley et al. 1995: 264).

“Instead of a decision appearing at a point in time, decision-making follows a general trajectory of gradual convergence on the image of some final action. Instead of conceiving decision making as a series of steps (or cycling imposed on a linear sequence…), it comes to be seen in a more integrative way as the construction of an issue” (Langley et al. 1995: 266).

Which may be a positive decision, a negative decision, or a non-decision.

A more detailed review of this literature is made in Cooremans (2011), in the sections “Capital Investment decision-making literature” and “Alternative energy literature: empirical findings.”

“Executives’ experiences, values, and personalities affect their field of vision (the directions they look and listen), selective perception (what they actually see and hear), and interpretation (how they attach meaning to what they see and hear)” (Hambrick 2007: 337).

i.e., Decisions “that have not been encountered in quite the same form and for which no predetermined and explicit set of ordered responses exists in the organization” (Mintzberg et al. 1976: 246). “This is not the decision making under uncertainty of the textbook, where alternatives are given even if their consequences are not, but decision making under ambiguity, where almost nothing is given or easily determined” (Mintzberg et al. 1976: 250).

“Politicality refers to the degree of influence which is brought to bear on a decision and how this influence is distributed within and without the organization… (Miller et al., in Clegg 1996: 300) The strength and distribution of influence, coupled with the complexity of what is being decided, shape the process which ensues” (idem: 301).

“Satisfying” here means a theoretical framework useful to scholars to analyze investment decisions made by firms as well as to decision makers to analyze investment projects.

For instance, out of the 25 strategic decisions studied by Mintzberg et al. (1976), 22 were investment decisions.

In this paper, Dutton et al. study the dimensions that decision makers employ to make strategic issue diagnosis or, in other words, to recognize, differentiate, and sort strategic issues, and how these dimensions are different from the ones researchers assume that decision makers use.

Identified in three sources and by their own research (Dutton et al. 1989: 383 and 388).

Most frequently cited by respondents to their survey (Dutton et al. 1989: 383 and 388).

Indeed, most authors in the field agree on the following elements which are deducted from Porter’s principles of competitive strategy (Porter 1985, 1980): Strategy sets out the basic direction of the organization, by specifying the organization’s long-term activities and goals, according to its internal resources and to external factors, in order to build a durable competitive advantage (Johnson and Scholes 1999: 27).

For a more detailed discussion about the concept and definition of “strategic nature,” please refer to the section “Defining strategic” in Cooremans ((2011) pp 486–487).

In this paper, content and definition of competitive advantage concept are discussed in detail.

Figures of the scale correspond to: 1 = completely unimportant; 2 = not important; 3 = moderately important; 4 = important; 5 = very important.

Investment profitability measures the relationship between the capital invested and the income which ensues from the investment. For a well-written description of capital budgeting methods, I suggest the following reading “Finance for Managers” pp. 140–170, Harvard Business Essential; Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA (2003).

Eighty-seven percent of positive answers in our sample. See Table 3 of the Appendix for detailed results.

Fifteen out of 17.

Ten positive answers out of 17 respondents.

As theorized by the political model of decision-making described in the paragraph “Decision making: a process influenced by actors’ power”. We received 14 positive answers out of 17 respondents to the assertion: “Investment decisions are influenced by the balance of power between a firm’s departments”. Please also refer to Table 3 of the Appendix.

Seventy-six percent of the answers, i.e., 13 yes, 4 no, and 1 non-answer to question F 9–11 (“Does the procedure depend on the investment amount?” Yes, No.)

Eighty-eight percent of the answers, i.e., 15 positive answers out of 17 and 1 non-answer to question F 9-19-1 (“Do the stages that a project has to follow depend on the investment amount?” Yes, No).

In 61 % of companies, i.e., 11 yes, 6 no, and 1 non-answer to question F 9–10 (“Do you apply different types of analysis to an investment project according to investment category?” Yes, No) and to question F 9–14 (“Does the financial method used to assess profitability depend on the investment category?” Yes, No).

Eight yes, nine no, and one non-answer to question F 9-19-2 (“Do the stages that a project has to follow depend on the investment category?” Yes, No).

Seventy-eight percent, or 14 out of 18. It is also the first category chosen by respondents in the de Bodt and Bouquin survey, although with a lower score (41 % of the answers, or 18 companies out of 44).

Competition between investments is described in the paragraph on Decision making: a process influenced by investment characteristics in the section “A new model of investment decision making.”

As per our definition, an investment is strategic if it contributes to create, maintain, or develop a sustainable competitive advantage.

“The responses shown here concern technologies about which firms had indicated earlier in the survey that they are aware of their existence, that the technologies were considered as being profitable, but that they were still not implemented as yet” (de Groot et al. 2001: 727).

See Table 3 of the Appendix for complete results.

A conclusion which would support the Rigby (2002) analysis which questions the quality of financial calculations made by companies: “In addition to the problem that organisations did not know how to save energy, it was also shown by market research studies carried out for BRECSU [Building Research Energy Conservation Support] that organisations did not know how to assess the economic potential of their investments in energy efficiency. The weaknesses in the financial methodologies used by energy managers and estates departments for estimating the profitability of energy efficient criteria principally included making errors in the estimate of the inflation rate and changes to future fuel prices. The result of these errors was to render “many investment appraisal analyses meaningless” (Building Research Energy Conservation Support, BRECSU, 1991: 6 quoted by Rigby 2002: 15).

Only four companies out of the 16 which answered question F 9-15-3 take risk into account at the project level to fix the discount rate.

Interview of February 22, 2007.

“and nearly 90 % of them were successfully granted loans” (IFC, 2006: 34).

The fact that strategic investments win the organizational competition for resources is described in the paragraph on Decision making: a process influenced by investment characteristics in the section “A new model of investment decision-making.”

See fourth line of Table 2.

i.e., Nine companies out of the 17 having answered this question; 1 no-answer.

Regarding the question of costs, it is interesting to note that, contrary to an idea commonly held but rarely discussed, energy costs are not automatically higher in proportion to turnover in companies of the secondary sector than in those of the tertiary sector.

That is the sum of the means of the results for variables 2_5_3, 2_5_4, and 2_5_5. See the section “Strategic nature concept measurement”.

That is the sum of the means of the results for variables 7_5_3, 7_5_4, and 7_5_5. See the section “Strategic nature concept measurement”. According to the Student’s t test, the difference between the results of energy managers and those of finance managers is not statistically significant.

Let us remember that figures of the scale correspond to: 1 = completely unimportant; 2 = not important; 3 = moderately important; 4 = important; 5 = very important.

However, the answers vary considerably between companies, according to their individual experiences in terms of electricity disruptions.

Question 7-5-7: “Do you think that adoption of energy efficient technologies is important for your company for benchmarking reasons (competition pressure).” Average of the answers is of 2.2 for energy managers (35 answer) and of 2.1 for finance managers (15 answers). Please classify in ascending order (1 = the least important; 5 = the most important).

Question 7-5-8: Do you think that adoption of energy-efficient technologies is important for your company for the following reasons? Corporate image towards clients ___________. Please classify in ascending order (1 = the least important – 5 = the most important). (Average of the answers is of 3.1 for energy managers (35 answers) and of 2.6 for finance managers (15 answers).)

“Costs reduction” entailed by energy-efficiency investments is rated generally higher than 4 (out of a maximum of 5) and often close to 5, while the dimensions “risks reduction” and “ increase of products value” almost always obtain a score lower than 3 out of 5.

Chemical, basic metals, metals, machinery, food, paper, horticulture, construction materials, and textiles industries.

They ranged from 4 to 13 (out of a maximum of 15) for energy managers and from 5 to 13 (out of 15) for finance managers.

9.16 Time horizon for profitability assessment is primarily determined by:

(Please mark adequate compartments)

O Fixed duration identical for all projects?

O Lifespan of equipments?

O Reasonable time horizon for forecasting?

O Strategic dimension of project

O Other? Please precise: _______________

Question F 10_6. For the profitability study (if realized), which was the time horizon of the energy-efficiency project (in number of years)? ________ years

Thirteen answers out of 18 and seven answers out of 18 to question F 9_16.

Energy-consuming installations such as HCV (heating cooling ventilation) have a life span of 15 to 20 years.

See Footnote 62 above.

As per our definition

With an average score of 2.8 out of 5.

See section “A new model of investment decision making”

As shown by Maritan (2001); see section on “Strategicity.”

See “Introduction”.

See the paragraphs on unorthodox behavior by companies in our survey, regarding capital budgeting methods (toward the end of section “General investment behavior”).

References

Alkaraan, F., & Northcott, D. (2006). Capital investment decision-making: A role for strategic management accounting. The British Accounting Review, 38(2), 49–73.

Anderson, S. T., & Newell, R. G. (2004). Information programs for technology adoption: The case of energy-efficiency audits. Resource and Energy Economics, 26(1), 27–50.

Bachrach, P., & Baratz, M. S. (1962). The two faces of power. American Political Science Review, 56, 947–952.

Burcher, P. G., & Lee, G. L. (2000). Competitiveness strategies and AMT investment decisions. Integrated Manufacturing Systems, 11(5), 340–347.

Butler, R. J. (1990). Studying deciding: an exchange of views between Mintzberg and Waters, Pettigrew and Butler. Organization Studies, 11(1), 2–16.

Butler, R., Davies, L., Pike, R., & Sharp, J. (1991). Strategic investment decision-making: Complexities, politics and processes. Journal of Management Studies, 28(4), 395–415.

Carr, C., & Tomkins, C. (1996). Strategic investment decisions: The importance of SCM. A comparative analysis of 51 case studies in U.K., U.S. and German companies. Management Accounting Research, 7(2), 199–217.

Chen, S. (1995). An empirical examination of capital budgeting techniques: Impact of investment types and firm characteristics. The Engineering Economist, 40(2), 145–170.

Cooremans, C. (2011). Make it strategic! Characteristics of investments do matter. Energy Efficiency, 4(4), 473–492.

Cyert, R., & March, J. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm and top level corporate decisions. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

De Bodt, E., & Bouquin, H. (2001). Le contrôle de l’investissement. In Images de l'investissement, Ouvrage collectif coordonné par G. Charreaux (pp. 115–166). Paris: Vuibert.

de Groot, H., Verhoef, E., & Nijkamp, P. (2001). Energy savings by firms: Decision- making, barriers AND policies. Energy Economics, 23(6), 717–740.

Dean, J. W., & Sharfman, M. P. (1993). Procedural rationality in the strategic decision-making process. Journal of Management Studies, 30(4), 587–610.

Dean, J. W., & Sharfman, M. P. (1996). Does decision-process matter? A study of strategic decision-making effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 368–396.

DeCanio, S. J. (1993). Barriers within firms to energy-efficient investments. Energy Policy, 21(9), 903–914.

DeCanio, S. J., & Watkins, W. E. (1998). Investment In energy efficiency: Do the characteristics of firms matter? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(1), 95–107.

Desreumaux, A., & Romelaer, P. (2001). Investissement et organisation. In G. Charreaux (Ed.), Images de l'investissement , ouvrage collectif (pp. 61–114). Paris: Vuibert, Coll. FNEGE.

Dutton, J., & Jackson, S. (1987). Categorizing strategic issues: Links to organizational action. Academy of Management Review, 12(1).

Dutton, J., Fahey, L., & Narayanan, V. K. (1983). Toward understanding strategic issue diagnosis. Strategic Management Journal, 4, 307–323.

Dutton, J. E., Walton, E. J., & Abrahamson, E. (1989). Important dimensions of strategic issues: Separating the wheat from the chaff. Journal of Management Studies, 26(4), 379–396.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Zbaracki, M. J. (1992). Strategic decision making. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 17–37.

Eyre, N. (1997). Barriers to energy efficiency: More than just market failure. Energy & Environment, 8(1), 25–43.

Golove W. H., & Eto, J. H. (1996). Market barriers to energy efficiency: A critical reappraisal of the rationale for public policies to promote energy efficiency. Energy & Environment Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, University of California.

Hambrick, D. C. (2007). Upper echelons theory: An update. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 334–343.

Hammond, J. S., Keeney, R. L., & Raiffa, H. (2001). The hidden traps in decision making. In Harvard business review on decision making (6th ed., pp. 143–167). Boston: Harvard Business School.

Harris, J., Anderson, J., & Shafron, W. (2000). Investment in energy efficiency: A survey of Australian firms. Energy Policy, 28(12), 867–876.

Harvard Business Essentials. (2003). Finance for managers. Boston: HBS Publishing Corporation.

Hickson, D. J., Butler, R. J., Cray, D., Mallory, G. R., & Wilson, D. C. (1986). Top decisions: Strategic decision-making in organizations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.