Opinion statement

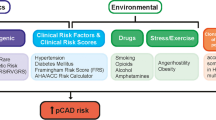

Although cardiovascular disease is commonly recognized as a disease of the elderly, young patients are also at risk for coronary atherosclerosis, which has a devastating impact on their more active lifestyle. In identifying patients at risk for a cardiovascular event, global risk models often fail to assess family history, an important risk factor in patients with premature coronary artery disease (P-CAD). P-CAD refers to the accelerated development of coronary atherosclerosis before age 55 in men and 65 in women, which may be the result of acquired or primary causes. Acquired P-CAD is associated with an underlying medical condition or influencing factor, such as systemic lupus erythematosus or cocaine use, that directly contributes to the rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis. It is important to evaluate young patients for acquired P-CAD because in many instances treatment may be tailored to the underlying medical condition. Most cases of P-CAD, however, are the result of primary causes involving more complex interactions among genetic, metabolic, and environmental risk factors. Patients with primary P-CAD usually have a family history of coronary disease, suggesting a strong genetic component. With the use of genome-wide association analysis, several chromosome loci have been identified as being linked to the development of coronary atherosclerosis and risk factors. The chromosome 9p21.3 locus, which is the most replicated to date, has provided some insight into the pathologic mechanism of coronary disease. The confirmation and replication of these associations through further study will lead to earlier detection of P-CAD in at-risk patients and a better understanding of the underlying pathologic mechanisms, thereby influencing the development of preventive therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al.: Heart disease and stroke statistics 2008 update. A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2008, 117:e25–e146.

Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, et al.: Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998, 97:1837–1847.

Michos E, Vasamreddy C, Becker D, et al.: Women with a low Framingham risk score and a family history of premature coronary heart disease have a high prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis. Am Heart J 2005, 150:1276–1281.

Lange R, Cigarroa J, Hills D, et al.: Theodore E. Woodward Award: cardiovascular complications of cocaine abuse. Trans Am Climatol Assoc 2004, 115:99–114.

Barton M, Dubez R, Traupe T, et al.: Oral contraceptives and the risk of thrombosis and atherosclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2002, 11:329–332.

Goldstein JL, Brown MS: Regulation of low density lipoprotein receptors: implications for pathogenesis and therapy for hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1987, 76:504–507.

Karadag O, Calquneri M, Atalar E, et al.: Novel cardiovascular risk factors and cardiac event predictors in female inactive lupus erythematosus patients. Clin Rheumatol 2007, 26:695–699.

Anderson JL, Adams C, Antman EM, et al.: ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007, 50:e1–e157.

Asanuma Y, Oeser A, Shintani A, et al.: Premature coronary artery atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2003, 349:2407–2415.

Engel H, Hundershagen H, Lichtlen P: Transmural myocardial infarction in young women taking oral contraceptives. Evidence of reduced coronary flow in spite of normal coronary arteries. Br Heart J 1977, 39:477–484.

Schiff I, Bell WR, Davis V, et al.: Oral contraceptives and smoking; current recommendations of a consensus panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999, 180:5383–5384.

Jomini V, Oppliger-Pasquali S, Wietlisbach V, et al.: Combination of major cardiovascular risk factors to familial premature coronary artery disease. The GENECARD project. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002, 40:676–684.

Juonola M, Viikari J, Rasanen L, et al.: Young adults with family history of coronary heart disease have increased arterial vulnerability to metabolic risk factors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006, 26:1376–1382.

Juonala M, Jarvisalo MJ, Maki-Torkko N, et al.: Risk factors identified in childhood and decreased carotid artery elasticity in adulthood. Circulation 2005, 112:1489–1496.

Clarkson P, Celermajer DS, Powe AJ, et al.: Endothelium-dependent dilatation is impaired in young healthy subjects with a family history of premature coronary disease. Circulation 1997, 96:3378–3383.

McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, et al.: A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science 2007, 316:1488–1491.

Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, et al.: A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science 2007, 316:1491–1493.

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortorium (WTCCC): Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of review of common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 2007, 447:661–678.

Talmud PJ, Bujac SR, Hall S, et al.: Substitution of asparagine for aspartic acid at residue 9 (D9N) of lipoprotein lipase markedly augments the risk of ischemic heart disease in male smokers. Atherosclerosis 2000, 149:78–81.

Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM, et al.: Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science 2007, 316:1336–1341.

Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al.: A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science 2007, 316:1341–1345.

Dressler FA, Malekzadeh S, Roberts WC, et al.: Quantitative analysis of amounts of coronary arterial narrowing in cocaine addicts. Am J Cardiol 1990, 65:303–308.

Ross, R: Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999, 340:115–126.

Axelrod L: Glucocorticoid therapy. Medicine 1976, 55:39–65.

Giannakopoulos B, Passam F, Rahgozar S, et al.: Current concepts on the pathogenesis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood 2007, 109:422–430.

Chen L, Chester M, Kaski JC: Clinical factors and angiographic features associated with premature coronary artery disease. Chest 1995, 108:364–369.

Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al.: Intensive lipid lowering therapy with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004, 350:1495–1504.

Bakker-Arkema RG, Davidson MH, Goldstein RJ, et al.: Efficacy and safety of a new HMG CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. JAMA 1996, 276:128–133.

Probstfield JL, Hunninghake DB: Nicotinic acid as a lipoprotein altering agent. Therapy directed by the primary physicians. Arch Intern Med 1994, 154:1557–1559.

Fruchart JC, Brewer HB, Leitersdorf E: Consensus for the use of fibrates in the treatment of dyslipoproteinemia and coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1998, 81:912–917.

Goldenberg I, Jonas M, Tenenbaum A, et al.: Current smoking, smoking cessation, and the risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med 2003, 163:2301–2305.

Critchley JA, Capewell S: Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2003, 290:86–97.

Physicians advice for smoking cessation: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004, CD000165.

Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, et al.: A controlled trial of sustained release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 1999, 340:685–691.

Lam W, Sze PC, Sacks HS, Chalmers TC: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of nicotine chewing gum. Lancet 1987, 2:27–30.

Gonzalez D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al.: Varenicline, an alpha 4 beta 2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist vs. sustained release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized control trial. JAMA 2006, 296:47–55.

McGill HC, McMahon CA, Herderick EE, et al.: Obesity accelerates the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in young men. Circulation 2002, 105:2712–2718.

Miller WC, Koceja DM, Hamilton EJ: A meta-analysis of the past 25 years of weight loss for research using diet, exercise, or diet plus exercise intervention. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1997, 21:941–947.

Kelley DE, Bray GA, Pi-Sunyer FX, et al.: Clinical efficacy of Orlistat therapy in overweight and obese patients with insulin treated type II diabetes: a 1 year randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2002, 25:1033–1041.

Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemma T, et al.: Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type II diabetes and non diabetic subjects with or without myocardial infarcts. N Engl J Med 1998, 339:229–234.

Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al.: Management of hyperglycemia in type II diabetes; a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy; a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29:1963–1972.

Hermann LS, Schersten B, Bitzen BO, et al.: Therapeutic comparison of metformin and sulfonylureas alone and in various combinations. A double blind study. Diabetes Care 1994, 17:1100–1109.

Schwartz S, Sievers R, Strange P, et al.: Insulin 70/30 mix plus metformin vs. triple oral therapy in treatment of type II diabetes after failure of two oral drugs; efficacy, safety, and cost analysis. Diabetes Care 2003, 26:2238–2243.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al.: The seventh report of the National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evolution, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003, 289:2560–2572.

Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al.: Effects of an angiotensinconverting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 2000, 342:145–153.

Mochizuki S, Dahlof B, Shimizu M, et al.: Valsartan in a Japanese population with HTN and other cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2007, 369:1431–1439.

Nissen SE, Tuzku EM, Libby P, et al.: Effects of antihypertensive agents on cardiovascular events in patients with coronary disease and normal blood pressure: the CAMELOT study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 292:2217–2226.

Poole-Wilson PA, Lubsen J, Kirwan BA, et al.: Effect of long-acting nifedipine on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in patients with stable angina requiring treatment (ACTION trial): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 364:849–857.

Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, et al.: Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004, 351:2049–2057.

Wegner N: The Reynolds Risk Score: improved accuracy for cardiovascular risk prediction in women. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2007, 4:366–367.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Person, A.F., Patterson, C. Therapeutic options for premature coronary artery disease. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 10, 294–303 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-008-0050-9

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-008-0050-9