Abstract

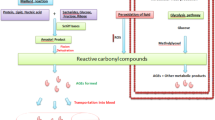

Diabetic vascular complications are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, such vascular disease is only incompletely explained by "traditional" risk factors in the nondiabetic complications. This situation has prompted the search for factors contributing to the pathogenesis of accelerated and more severe vascular disease in patients with diabetes. We review evidence that receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), via its interaction with ligands, serves as a cofactor exacerbating diabetic vascular disease. RAGE is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell surface molecules with a diverse repertoire of ligands reminiscent of pattern recognition receptors. In the diabetic milieu, two classes of RAGE ligands, products of nonenzymatic glycoxidation and S100 proteins, appear to drive receptor-mediated cellular activation and, potentially, acceleration of vascular disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Diabetes mellitus: a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. A joint editorial statement by the American Diabetes Association; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and the American Heart Association [no authors listed]. Circulation 1999, 100:1132–1133.

Kannel W: Lipids, diabetes, and coronary heart disease: insights from the Framingham study. Am Heart J 1985, 110:1100–1107.

Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton J, Wentworth D: Diabetes, other risk factors and 12-year cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care 2003, 16:434–444.

Beckman J, Craeger M, Libby P: Diabetes and atherosclerosis. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. JAMA 2002, 287:2570–2581.

Intensive blood glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group [no authors listed]. Lancet 1998, 352:837–853.

Stratton I, Adler A, Neil H, et al.: Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000, 321:405–412.

Kastrati A, Schomig A, Elezi S, et al.: Predictive factors of restenosis after coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997, 30:1428–1436.

Mazeika P, Prasad N, Bui S, Seidelin P: Predictors of angio-graphic restenosis after coronary intervention in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am Heart J 2003, 145:1013–1021.

Kornowski R, Mintz G, Kent K, et al.: Increased restenosis in diabetes mellitus after coronary interventions is due to exaggerated intimal hyperplasia. Circulation 1997, 95:1366–1369.

Takagi T, Yamamuor A, Tamita K, et al.: Pioglitazone reduces neointimal tissue proliferation after coronary stent implantation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: an intravascular ultrasound scanning study. Am Heart J 2003, 146:E5.

Phillips J, Barringhaus K, Sander J, et al.: Rosiglitazone reduces accelerated neointima formation after arterial injury in a mouse injury model of type 2 diabetes. Circulation 2003, 108:1994–1999.

Schmidt AM., Vianna M, Gerlach M, et al.: Isolation and characterization of binding proteins for advanced glycosylation end products from lung tissue which are present on the endothelial cell surface. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:14987–14997.

Neeper M, Schmidt AM, Brett J, et al.: Cloning and expression of RAGE: a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:14998–15004.

Brownlee M: Advanced protein glycosylation in diabetes and aging. Annu Rev Med 1996, 47:223–234.

Kislinger T, Fu C, Huber B, et al.: N(epsilon)(carboxymethyl) lysine adducts of proteins are ligands for RAGE that activate cell signalling pathways and modulate gene expression. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:31740–31749.

Thornalley P: Cell activation by glycated proteins: AGE receptors, receptor recognition factors and functional classification of AGEs. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1998, 44:1013–1023.

Hofmann M, Drury S, Caifeng F, et al.: RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: the cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell 1999, 7:889–901.

Hori O, Brett J, Slattery T, et al.: The receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is a cellular binding site for amphoterin. Mediation of neurite outgrowth and co-expression of RAGE and amphoterin in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:25752–25761.

Chavakis T, Bierhaus A, Al-Fakhri N, et al.: The patter recognition receptor RAGE is a counterreceptor for leukocyte integrins: a novel pathway for inflammatory cell recruitment. J Exp Med 2003, 198:1507–1515.

Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, et al.: RAGE in Alzheimer’s disease: a receptor mediating amyloid-beta peptide-induced oxidant stress and neurotoxicity and microglial activation. Nature 1996, 382:685–691.

Roth J, Vogl T, Sorg C, Sunderkotter C: Phagocyte-specific S100 proteins: a novel group of proinflammatory molecules. Trends Immunol 2003, 24:155–158.

Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, et al.: HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 1999, 285:248–251.

Sipe J: Amyloidosis. Annu Rev Biochem 1992, 61:947–975.

Deane R, Yan SD, Submamaryan RK, et al.: RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain, suppression of cerebral blood flow and development of cerebral amyloidosis. Nat Med 2003, 9:907–913.

Arancio O, Zhang HP, Chen X, et al.: RAGE potentiates Abeta-induced perturbation of neuronal function in transgenic mice. EMBO J 2004, 23:4096–4105.

Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern D: RAGE: a multiligand receptor serving as a progression factor amplifying the immune/ inflammatory response. J Clin Invest 2001, 108:949–955. This review article summarizes the biology of RAGE in a variety of contexts, in addition to the area of vascular disease described in the current paper.

Bouma B, Kroon-Batenburg L, Wu YP, et al.: Glycation induces formation of amyloid cross-beta structure in albumin. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:41810–41819.

Ishihara K, Tsutusmi K, Kawane S, et al.: RAGE directly binds to ERK by a D-domain-like docking site. FEBS Lett 2003, 550:107–113.

Brizzi M, Dentelli P, Rosso A, et al.: RAGE- and TGF-beta receptor-mediated signals converge on STAT5 and p21waf to control cell-cycle progression of mesangial cells: a possible role in the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy. FASEB J 2004, 18:1249–1251.

Shaw SS, Schmidt AM, Banes AK, et al.: S100B-RAGE-mediated augmentation of angiotensin ii-induced activation of JAK2 in vascular smooth muscle cells is dependent on PLD2. Diabetes 2003, 52:2381–2388.

Li J, Huang X, Zhu H, et al.: AGEs activate Smad signaling via TGF-beta-dependent and independent mechanisms: implications for diabetic renal and vascular disease. FASEB J 2004, 18:176–178.

Huttunen J, Kuja-Panula J, Rauvala H: RAGE signaling induces CREB-dependent chromogranin expression during neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem 2002, 277:38635–38646.

Huttunen H, Fages C, Rauvala H: RAGE-mediate neurite outgrowth and activation of NF-kappaB require the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor but different downstream signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:19919–19924.

Wautier MP, Chappey O, Corda S, et al.: Activation of NADPH oxidase by AGEs links oxidant stress to altered gene expression via RAGE. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001, 280:E685-E694.

Wells-Knecht K, Zyzak D, Litchfield J, et al.: Mechanism of autoxidative glycosylation: identification of glyoxal and arabinose as intermediates in the autoxidative modification of proteins by glucose. Biochemistry 1995, 21:3702–3709.

Nagai R, Ikeda K, Highashi T, et al.: Hydroxyl radical mediates N-epsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine formation from Amadori product. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997, 234:167–172.

Fu M, Requena J, Jenkins A, et al.: The AGE, N-epsilon- (carboxymethyl)lysine, is a product of both lipid peroxidation and glycoxidation reactions. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:9982–9986.

Nagai R, Unno Y, Hayashi M, et al.: Peroxynitrite induces formation of N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine by the cleavage of Amadori product and generation of glucosone and glyoxal from glucose: novel pathways for protein modification by peroxynitrite. Diabetes 2002, 51:2833–2839.

Anderson M, Requena, J, Crowley J, et al.: The myeloperoxidase system of human phagocytes generates N-epsilon-(carboxymethyl) lysine on proteins: a mechanism for producing AGEs at sites of inflammation. J Clin Invest 1999, 104:103–113.

Schalkwijk C, Baidoshvili A, Stehouwer C, et al.: Increased accumulation of the glycoxidation product N(epsilon)- (carboxymethyl)lysine in hearts of diabetic patients; generation and characterization of a monoclonal anti-CML antibody. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004, 1636:82–89.

Nerlich A, Schleicher E: N-epsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine in atherosclerotic vascular lesions as a marker for local oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis 1999, 144:41–47.

Park L, Raman K, Lee K, et al.: Suppression of accelerated diabetic atherosclerosis by soluble receptor for AGE (sRAGE). Nat Med 1998, 4:1025–1031.

Wautier JL, Zoukourian C, Chappey O, et al.: Receptor-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction in diabetic vasculopathy: soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products blocks hyperpermeability. J Clin Invest 1996, 97:238–243.

Kislinger T, Tanji N, Wendt T, et al.: Receptor for advanced glycation end products mediates inflammation and enhanced expression of tissue factor in the vasculature of diabetic apolipoprotein E null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001, 21:905–910.

Bucciarelli LG, Wendt T, Qu W, et al.: RAGE blockade stabilizes established atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation 2002, 106:2827–2835.

Moreno P, Fallon J, Murcia A, et al.: Tissue characteristics of restenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in diabetic patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999, 34:1045–1049.

Sakaguchi T, Yan SF, Yan SD, et al.: Central role of RAGE-dependent neointimal expansion in arterial restenosis. J Clin Invest 2003, 111:959–972.

Seki Y, Kai H, Shibata R, et al.: Role of the JAK/STAT pathway in rat carotid artery remodeling after vascular injury. Circ Res 2000, 87:12–18.

Zhou A, Wang K, Penn MS, et al.: Receptor for AGE (RAGE) mediates neointimal formation in response to arterial injury. Circulation 2003, 107:2238–2243. The authors report on a model carotid artery de-endothelialization in which diabetic (type 2) rats develop more extensive neointimal expansion than nondiabetic animals. This model system is likely to be useful to others studying mechanisms of vascular dysfunction in the context of diabetes.

Liliensiek B, Weigand MA, Bierhaus A, et al.: Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) regulating sepsis but not the adaptive immune response. J Clin Invest 2004, 113:1641–1650. This paper describes the role of RAGE in innate immunity, based on studies showing a protective phenotype in the setting of Escherichia coli sepsis (cecal ligation and puncture) compared with control animals.

Park J, Svetkauskaite D, He Q, et al.: Involvement of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. J Bio Chem 2004, 279:7370–7377.

Fujita T, Asai T, Andrassy M, et al.: PKCbeta regulates ischemia/ reperfusion injury in the lung. J Clin Invest 2004, 113:1615–1623.

Yan SF, Fujita T, Lu J, et al.: EGR-1, a master switch coordinating upregulation of divergent gene families underlying ischemic stress. Nat Med 2000, 6:1355–1361.

Yan SF, Lu J, Zou YS, et al.: Protein kinase C-beta and oxygen deprivation: a novel Egr-1-dependent pathway for fibrin deposition in hypoxemic vasculature. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:11921–11928.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nawroth, P., Bierhaus, A., Marrero, M. et al. Atherosclerosis and restenosis: Is there a role for rage?. Curr Diab Rep 5, 11–16 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-005-0061-9

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-005-0061-9