Abstract

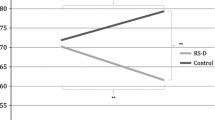

Orthographic spelling is a major difficulty in German-speaking children with dyslexia. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an orthographic spelling training in spelling-disabled students (grade 5 and 6). In study 1, ten children (treatment group) received 15 individually administered weekly intervention sessions (60 min each). A control group (n = 4) did not receive any intervention. In study 2, orthographic spelling training was provided to a larger sample consisting of a treatment group (n = 13) and a delayed treatment control group (n = 14). The main criterion of spelling improvement was analyzed using an integrated dataset from both studies. Repeated-measures analysis of variance revealed that gains in spelling were significantly greater in the treatment group than in the control group. Statistical analyses also showed significant improvements in reading (study 1) and in a measure of participants’ knowledge of orthographic spelling rules (study 2). The findings indicate that an orthographic spelling training enhances reading and spelling ability as well as orthographic knowledge in spelling-disabled children learning to spell a transparent language like German.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arnold, E. M., Goldston, D. B., Walsh, A. K., Reboussin, B. A., Daniel, S. S., Hickman, E., et al. (2005). Severity of emotional and behavioral problems among poor and typical readers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 205–217.

Aro, M., & Wimmer, H. (2003). Learning to read: English in comparison to six more regular orthographies. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 621–635.

Borgwaldt, S. R., Hellwig, F. M., & de Groot, A. M. B. (2004). Word-initial entropy in five languages. Written Language and Literacy, 7, 165–184.

Bourassa, D. C., & Treiman, R. (2003). Spelling in children with dyslexia: analyses from the Treiman-Bourassa early spelling test. Scientific Studies of Reading, 7, 309–333.

Bruck, M. (1993). Component spelling skills of college students with childhood diagnoses of dyslexia. Learning Disability Quarterly, 16, 171–184.

Caravolas, M. (2004). Spelling development in alphabetic writing systems: a cross-linguistic perspective. European Psychologist, 9, 3–14.

Caravolas, M., & Bruck, M. (1993). The effect of oral and written language input on children’s phonological awareness: a cross-linguistic study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 55, 1–30.

Caravolas, M., Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2001). The foundations of spelling ability: evidence from a 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Memory and Language, 45, 751–774.

Cassar, M., Traiman, R., Moats, L., Pollo, T. C., & Kessler, B. (2005). How do the spellings of children with dyslexia compare with those of nondyslexic children? Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 27–49.

Cunningham, A. E., Perry, K. E., Stanovich, K. E., & Share, D. L. (2002). Orthographic learning during reading: examining the role of self-teaching. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 82, 185–199.

Daniel, S. S., Walsh, A. K., Goldston, D. B., Arnold, E. M., Reboussin, B. A., & Wood, F. B. (2006). Suicidality, school dropout, and reading problems among adolescents. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, 507–514.

De Jong, P. F., & Share, D. L. (2007). Orthographic learning during oral and silent reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11(1), 55–71.

Dunlop, W. P., Cortina, J. M., Vaslow, J. B., & Burke, M. J. (1996). Meta-analysis of experiments with matched groups or repeated measures designs. Psychological Methods, 1, 170–177.

Eckert, T., & Stein, M. (2004). Ergebnisse aus einer Untersuchung zum orthographischen Wissen von HauptschülerInnen [Results of a study on orthographic knowlegde in students attending general education secondary school]. In U. Bredel, G. Siebert-Ott, & T. Thelen (Eds.), Schriftspracherwerb und Orthographie. Hohengehren: Schneider.

Esser, G., & Schmidt, M. (1993). Die langfristige Entwicklung von Kindern mit Lese-Rechtschreibschwäche [Long-term outcome of children with specific reading retardation]. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie, 22, 100–116.

Esser, G., Wyschkon, A., & Schmidt, M. (2002). Was wird aus Achtjährigen mit einer Lese- und Rechtschreibstörung [Long-term outcome in 8-year-old children with specific reading retardation: results at age 25 years]. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 31(4), 235–242.

Fluss, J., Ziegler, J. C., Warszawski, J., Ducot, B., Richard, G., & Billard, C. (2009). Poor reading in French elementary school: the interplay of cognitive, behavioral and socioeconomic factors. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(3), 206–216.

Friend, A., & Olson, R. K. (2008). Phonological spelling and reading deficits in children with spelling disabilities. Scientific Studies of Reading, 12, 90–105.

Frith, U., Wimmer, H., & Landerl, K. (1998). Differences in phonological recoding in German- and English-speaking children. Scientific Studies of Reading, 2(1), 31–54.

Grund, M. (2003). RST 4-7. Rechtschreibtest für 4-7. Klassen [RST 4-7. Spelling test for grades 4 to 7]. Baden-Baden: Computer & Lernen.

Ho, C. S., Law, T. P., & Ng, P. M. (2000). The phonological deficit hypothesis in Chinese developmental dyslexia. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 13, 57–79.

Jorm, A. F., & Share, D. L. (1983). Phonological recoding and reading acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics, 4, 103–147.

Katusic, S. K., Colligan, R. C., Barbaresi, W. J., Schaid, D. J., & Jacobsen, S. J. (2001). Incidence of reading disability in a population-based birth cohort, 1976–1982, Rochester, Minn. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 76, 1081–1092.

Kemp, N., Parrila, R. K., & Kirkby, J. R. (2009). Phonological and orthographic spelling in high-functioning adult dyslexics. Dyslexia, 15, 105–128.

Klicpera, C., & Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. (2000). Sind Rechtschreibschwierigkeiten Ausdruck einer phonologischen Störung? [Are spelling difficulties an expression of a phonological deficit?]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 32(3), 134–142.

Klicpera, C., Schabmann, A., & Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. (1993). Lesen- und Schreibenlernen während der Pflichtschulzeit: Eine Längsschnittuntersuchung über die Häufigkeit und Stabilität von Lese- und Rechtschreibschwierigkeiten in einem Wiener Schulbezirk [The development of reading and spelling skills from second to eighth grade: a longitudinal study on the frequency and stability of reading and spelling retardation in a Viennese school district]. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, 21, 214–255.

Landerl, K. (2003). Categorization of vowel length in German poor speller: an orthographically relevant phonological distinction. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 523–538.

Landerl, K., & Reitsma, P. (2005). Phonological and morphological consistency in the acquisition of vowel duration spelling in Dutch and German. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 92, 322–344.

Landerl, K., & Wimmer, H. (2000). Deficits in phoneme segmentation are not the core problem of dyslexia: evidence from German and English children. Applied Psycholinguistics, 21, 243–262.

Landerl, K., & Wimmer, H. (2008). Development of word reading fluency and spelling in a consistent orthography: an 8-year follow-up. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 150–161.

Landerl, K., Wimmer, H., & Frith, U. (1997). The impact of orthographic consistency on dyslexia: a German-English comparison. Cognition, 63, 315–334.

Lenhard, W., & Schneider, W. (2006). ELFE 1-6 Ein Leseverständnistest für Erst- bis Sechsklässler. [ELFE 1-6 A reading comprehension test for students from the 1st through the 6th grade]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Lindgren, S. D., DeRenzi, E., & Richman, L. C. (1985). Cross-national comparisons of developmental dyslexia in Italy and the United States. Child Development, 56, 1404–1417.

Lovett, M. W., Borden, S. L., DeLuca, T., Lacerenza, L., Benson, N. J., & Brackstone, D. (1994). Treating the core deficits of developmental dyslexia: evidence of transfer of learning after phonologically- and strategy-based reading training programs. Developmental Psychology, 30, 805–822.

Manis, F. R., Custodio, R., & Szeszulski, P. A. (1993). Development of phonological and orthographic skill: a 2-year longitudinal study of dyslexic children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 56, 64–86.

Mannhaupt, G. (2002). Evaluation von Förderkonzepten bei Lese-Rechtschreibschwierigkeiten—Ein Überblick [Evaluation of treatment approaches for children with reading and spelling difficulties—an overview]. In G. Schulte-Körne (Ed.), Legasthenie: Zum aktuellen Stand der Ursachenforschung, der diagnostischen Methoden und der Förderkonzepte (pp. 243–258). Bochum: Winkler.

Maughan, B. (1995). Annotation: long-term outcomes of developmental reading problems. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry and allied disciplines, 36, 357–371.

Maughan, B., Hagell, A., Rutter, M., & Yule, W. (1994). Poor readers in secondary school. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 6, 125–150.

Maughan, B., Rowe, R., Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2003). Reading problems and depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 219–229.

Morgan, P. L., Farkas, G., Tufis, P. A., & Sperling, R. A. (2008). Are reading and behavior problems risk factors for each other? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(5), 417–436.

Paulesu, E., Démonet, J.-F., Fazio, F., McCrory, E., Chanoine, V., Brunswick, N., et al. (2001). Dyslexia: cultural diversity and biological unity. Science, 291, 2165–2167.

Pennington, B. F., McCabe, L. L., Smith, S. D., Lefly, D. L., Bookman, M. O., Kimberling, W. J., et al. (1986). Spelling errors in adults with a form a familial dyslexia. Child Development, 57, 1001–1013.

Rack, J. P., Snowling, M. J., & Olson, R. K. (1992). The nonword reading deficit in developmental dyslexia: a review. Reading Research Quarterly, 27, 29–53.

Reuter-Liehr, C. (1993). Behandlung der Lese-Rechtschreibstörung nach der Grundschulzeit: Anwendung und Überprüfung eines Konzeptes [Treatment of dyslexia after grade 4: evaluation of a new approach]. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, 21, 135–147.

Scerri, T. S., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2009). Genetics of developmental dyslexia. European Child and Adolescence Psychiatry. doi:10.1007/s00787-009-0081-0.

Schneider, W., Küspert, P., Roth, E., Visé, M., & Marx, H. (1997). Short- and long-term effects of training phonological awareness in kindergarten: evidence from two German studies. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 66, 311–340.

Schulte-Körne, G., & Mathwig, F. (2009). Das Marburger Rechtschreibtraining—Ein regelgeleitetes Förderprogramm für rechtschreibschwache Kinder (4th edition) [The Marburg Spelling Training—a rule-based treatment program for children with spelling difficulties]. Bochum: Winkler.

Schulte-Körne, G., Schäfer, J., Deimel, W., & Remschmidt, H. (1997). Das Marburger Eltern-Kind-Rechtschreibtraining [The Marburg parent-child spelling training program]. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, 25, 151–159.

Schulte-Körne, G., Deimel, W., & Remschmidt, H. (1998). Das Marburger Eltern-Kind-Rechtschreibtraining—verlaufsuntersuchung nach zwei Jahren [The Marburg parent-child spelling training—follow up after two years]. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, 3, 167–173.

Schulte-Körne, G., Deimel, W., Hülsmann, J., Seidler, T., & Remschmidt, H. (2001). Das Marburger Rechtschreib-Training—Ergebnisse einer Kurzzeit-Intervention [The Marburg Spelling Training Program—results of a short-term intervention]. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 29, 7–15.

Schulte-Körne, G., Deimel, W., & Remschmidt, H. (2003). Rechtschreibtraining in schulischen Fördergruppen—ergebnisse einer Evaluationsstudie in der Primarstufe [Spelling training in school based intervention groups—results of an evaluation trial in secondary school]. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 31, 85–98.

Seymour, P. H. K., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 143–174.

Share, D. L. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55, 151–218.

Share, D. L. (1999). Phonological recoding and orthographic learning: a direct test of the self-teaching hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 72, 95–129.

Shaywitz, S. E., Shaywitz, B. A., Fletcher, J. M., & Escobar, M. D. (1990). Prevalence of reading disability in boys and girls. Journal of the American Medical Association, 264, 998–1002.

Stevenson, H. W., Stigler, J. W., Lucker, G. W., & Lee, S. (1982). Reading disabilities: the case of Chinese, Japanese, and English. Child Development, 53, 1164–1181.

Stone, G. O., Vanhoy, M., & Van Orden, G. C. (1997). Perception is a two-way street: feed forward and feedback phonology in visual word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 36, 337–359.

Tijms, J., & Hoeks, J. (2005). A computerized treatment of dyslexia: benefits from treating lexico-phonological processing problems. Dyslexia, 11, 22–40.

Tijms, J., Hoeks, J. J. W. M., Paulussen-Hoogeboom, M. C., & Smolenaars, A. J. (2003). Long-term effects of a psycholinguistic treatment for dyslexia. Journal of Research in Reading, 26, 121–140.

Torgesen, J. K., Alexander, A. W., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Voeller, K. K. S., & Conway, T. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34, 33–58.

van Otterloo, S. G., van der Leij, A., & Henrichs, L. F. (2009). Early home-based intervention in the Netherlands for children at familial risk of dyslexia. Dyslexia, 15(3), 187–217.

Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C. A., Hecht, S. A., Barker, T. A., Burgess, S. R., et al. (1997). Changing relations between phonological processing abilities and word-level reading as children develop from beginning to skilled readers: a 5-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 33, 468–479.

Weiß, R. H. (2006). CFT 20-R Grundintelligenztest Skala 2 (revision) [Culture Fair Test Scale 2—revision]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Wimmer, H. (1993). Characteristics of developemental dyslexia in a regular writing system. Applied Psycholinguistics, 14, 1–33.

Wimmer, H. (1996). The early manifestation of developmental dyslexia: evidence from German children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 8, 171–188.

Wimmer, H., & Goswami, U. (1994). The influence of orthographic consistency on reading development: word recognition in English and German children. Cognition, 51, 91–103.

Wimmer, J., & Hartl, M. (1991). Erprobung einer phonologischen multisensorischen Förderung bei jungen Schülern mit Lese-Rechtschreibschwierigkeiten [Evaluation of a phonological multisensoric treatment in young students with reading and spelling difficulties]. Heilpädagogische Forschung, 2, 74–79.

Wimmer, H., & Landerl, K. (1997). How learning to spell German differs from learning to spell English. In C. A. Perfetti, L. Rieben, & M. Fayol (Eds.), Learning to spell: research, theory and practice across languages. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Wimmer, H., Mayringer, H., & Landerl, K. (2000). The double-deficit hypothesis and difficulties in learning to read a regular orthography. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 668–680.

Ziegler, J. C., Perry, C., Ma-Wyatt, A., Ladner, D., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2003). Developmental dyslexia in different languages: language-specific or universal? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 86, 169–193.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Christina Boronkay, Frances Bühn, Sandra Geldmacher, Sarah Gerstner, Carina Günther, Anne Hoyler, Meike Kampert, Marcia Klimek, Sabine Kürzinger, Josefine Rothe, Anton Stumpf, Romina Sukiennicki, and Isabelle Wenig for their help in collecting data and conducting training sessions. The work reported in this article was done in partial fulfillment of the first author’s dissertation at the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Munich, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2: description of the orthographic spelling training

Background

The orthographic spelling training used in this study is based on the Marburger Rechtschreibtraining [Marburg Spelling Training] (Schulte-Körne & Mathwig, 2009), which is an orthographic spelling training for German-speaking spelling-disabled children in grade 2 and older. The effectiveness of the Marburg Spelling Training in enhancing spelling ability has been demonstrated in several studies (Schulte-Körne et al., 1997, 1998, 2001, 2003). The original version was modified for use with older students in several ways. (1) The overall design was changed. The frame story is now age-appropriate and algorithms are shaped like metro maps. (2) The new program contains age-appropriate word material and texts. (3) The main themes are conserved (e.g., consonant doubling, markers of long vowel phonemes) but are now trained in more detail: the new program also trains the more complex extensions of spelling rules (e.g., the doubling of the letters k and z). In addition, new rules as introduced (e.g., spelling of the different s-sounds).

Frame story

Summary of introduction

Some people have a good orientation and hardly ever get lost. Others do not have a good orientation and might get lost from time-to-time. If you cannot find your way back home, there are two possibilities: you can ask someone to show you the way, or you can have a look at a map. With spelling, it is quite similar. Some people have good spelling skills and hardly ever misspell a word. Others have difficulties remembering the right spellings. You can always ask someone how to spell a word. But would not it be great to have a map that shows you the way to the right spelling? You will soon meet two children (Lotte and Moritz) who will go on a journey to get some spelling maps. They will guide you through the program.

General aspects

-

1.

The spelling rules to be learned are not simply presented to the children. Whenever possible, children are guided by carefully chosen questions to discover the underlying spelling rule.

-

2.

Whenever possible, children are encouraged to use the algorithms during spelling tasks.

-

3.

Each chapter’s exercises increase in difficulty. After the learning a new rule, children complete one or several exercises that involve inserting single graphemes into incomplete words. The next exercises involve the spelling of whole words. Likewise, each chapter starts with exercises in which the children need to attend to only one rule (or algorithm). Subsequently, exercises are introduced that require the application of the newly learned spelling rule as well as previously learned spelling rules.

-

4.

Each chapter contains exercises that are intended to enhance a deeper understanding of the spelling rules. For example, children might be asked to explain the spelling of an inflected verb, which requires insight into the principle of morphological consistency.

Specification of content, organization, and instructional procedures of each chapter

-

Chapter 1:

Children learn to differentiate short and long vowel phonemes and to mark a short vowel with a dot and a long vowel with a line. Subsequently, selected word material is presented and the children are asked to (1) mark long and short vowel phonemes, and (2) draw a circle around the consonants phonemes that follow the vowel phoneme. They thereby discover the first spelling rule: “If a short vowel phoneme is followed by only one consonant phoneme within the same morpheme, then this consonant has to be doubled in the spelling”. The presentation of the algorithm is followed by examples demonstrating how the algorithm can be applied to words. After several exercises on simple consonant doubling, the more complex doubling of the consonants k (doubling: ck, as in Stock [stick]) and z (doubling: tz, as in Satz [sentence]) are introduced.

-

Chapter 2:

German closely adheres to the principle of morpheme consistency. In chapter 2, children learn that spelling rules only apply to the word stem, which is consequently spelled with high consistency. Children learn to identify the word stem in verbs, nouns, and adjectives. They are also introduced to common prefixes and endings, whose spellings have to be memorized as they are not conform orthographic spelling rules. The chapter contains exercises on adding prefixes and endings to incomplete words, exercises on identifying the word stem in verbs and adjectives (based on their uninflected form), exercises on morphological consistency, exercises on complex nouns with two word stems (e.g., Gepäckwagen [baggage bar]), exercises on the syllables end- and ent- (as in endlich [finally]) and entscheiden [to decide]) that sound similar but differ in meaning (words with end- relate to Ende [end]), and exercises in which the child writes words to dictation (prefixes and endings are given). In addition, consonant doubling is repeated throughout the chapter.

-

Chapter 3:

The goal of chapter 3 is to convey the spelling of capital initial letters. Five spelling rules are trained, namely: a word is spelled with a capital initial letter if (1) it is the first word in a sentence, (2) it is a name, (3) it is a noun, (4) it is the first word after a colon (only if a complete sentence follows), or (5) it is one of the pronouns you and your occurring in a letter or direct speech. German-speaking children with spelling disability usually demonstrate knowledge of these rules, but have difficulty in applying this knowledge. The chapter therefore starts with an exercise, in which a sentence is given and the children are asked to explain why three of the words are spelled with capital initial letters. Moritz admits that he often forgets to apply these rules during spelling and throughout the chapter children are encouraged to correct his texts. Further exercises include the spelling of pronouns in a letter and the marking of the correct spelling of names, nouns, and first words in a sentence. In the remaining chapters of the spelling training, Moritz repeatedly reminds the child to check the spelling of initial capital letters. Chapter 3 also provides additional material for advanced learners. In German, nominalizations are spelled with capital initial letters. The additional material provides exercises on how to identify a nominalization in a sentence, as this can be quite a challenge in German sentences. Previous topics are reviewed intensively throughout chapter 3.

-

Chapter 4:

There are several possibilities to mark long vowel phonemes. Chapter 4 trains two of these: the “silent h” (e.g., Ha h n [cock]) and the “vowel separating h” (e.g., se h en [to see]). In the frame story, Lotte and Moritz are surprised by a sudden rainfall and their map for markers of long vowel phonemes gets wet. Some of the stations are now covered by water drops and are illegible. The children’s task is to fill in the water drops one-by-one. They first learn about the green line, which leads to the final stations “silent h” and “no silent h”. Selected word material is given and the children are asked to circle the consonant they hear after the long vowel phoneme (the silent h is not audible). The children thereby discover the spelling rule “If a long vowel phoneme is directly followed by any of these consonants phonemes l, m, n or r, then a ‘silent h’ is used to mark vowel length (e.g., Pfa h l [pile], U h r [clock]). Likewise, children are lead to discover the next rule “If a word stem begins with any of the consonant graphemes t, sch, sp and q, then it does not have a ‘silent h’” (e.g., Tal [valley], Spur [trace]). The children now have sufficient information to fill in the two water drops that have masked stations of the green line. The children then complete exercises in which they need to apply the algorithm depicted by the green line and review earlier topics. Subsequently, they discover the next rule: “Two vowels are separated by a ‘vowel separating h’”. They can now fill in the water drop that covers a station of the blue line which leads to the final station ‘vowel separating h’. After the completion of exercises that require the application of the blue line, the children do exercises that require application of all rules learned so far, as well as exercises reviewing earlier topics and one exercise highlighting exceptions from the rules learned in this chapter.

-

Chapter 5:

The goal of chapter 5 is to convey the spelling of the long vowel phoneme i. The children first learn that if the vowel i is a long vowel phoneme, then it is spelled with the bigram ie (e.g., Tier [animal]). After completion of exercises in which the children have to decide whether a word is written with the grapheme i or with the bigram ie, the children learn that the three pronouns ihm, ihn, and ihr [him, his, her], which have a long vowel phoneme i, are spelled with the bigram ih. They then receive a map that contains an orange line for consonant doubling, a green line for the ‘silent h’, a blue line for the ‘vowel-separating-h’, and a yellow line with the final stations ‘ie’ and ‘ih’. The chapter continues with exercises in which children need to apply only the yellow line, as well as exercises, in which the whole map must be used. In addition, there are exercises on the spellings of endings that contain the phoneme i but are not spelled conform the spelling rules (e.g., Rosine [raisin], which has a long vowel phoneme i, but is not spelled with the bigram ie). There are also exercises on the spellings of the words wider and wieder, which sound similar but differ in meaning: the word wider relates to against (as in Widerstand [opposition]), while the word wieder relates to again (as in Wiederholung [repetition]). Previous topics are reviewed throughout the chapter.

-

Chapter 6:

Chapter 6 introduces a map depicting an algorithm for the different s-sounds (e.g., Glä s er [glasses], Grü ß e [greetings], Kü ss e [kisses]). As in previous chapters, children are first given selected word material, asked to mark long and short vowels and to circle the consonants following the vowel phonemes. The children thereby discover that the graphemes s or ß follow a long vowel phoneme, while the bigrams ss, st, sp, or sk follow a short vowel phoneme. There is no rule that specifies whether a word contains the grapheme s or the grapheme ß. However, the sounds of the two graphemes differ and children are intensively trained to differentiate these two sounds. Chapter 6 also contains exercises on applying the new algorithm, as well as exercises reviewing previous topics and one exercise highlighting exceptions from the rules learned in this chapter. Figure 2 depicts the algorithm for the spelling of the different s-sounds.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ise, E., Schulte-Körne, G. Spelling deficits in dyslexia: evaluation of an orthographic spelling training. Ann. of Dyslexia 60, 18–39 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-010-0035-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-010-0035-8