ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

The relative contributions of depression, cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND), and dementia to the risk of potentially preventable hospitalizations in older adults are not well understood.

OBJECTIVE(S)

To determine if depression, CIND, and/or dementia are each independently associated with hospitalizations for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (ACSCs) and rehospitalizations within 30 days after hospitalization for pneumonia, congestive heart failure (CHF), or myocardial infarction (MI).

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS

Population-based sample of 7,031 Americans > 50 years old participating in the Health and Retirement Study (1998–2008).

MAIN MEASURES

The eight-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale and/or International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) depression diagnoses were used to identify baseline depression. The Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status and/or ICD-9-CM dementia diagnoses were used to identify baseline CIND or dementia. Primary outcomes were time to hospitalization for an ACSC and presence of a hospitalization within 30 days after hospitalization for pneumonia, CHF, or MI.

KEY RESULTS

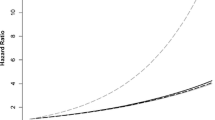

All five categories of baseline neuropsychiatric disorder status were independently associated with increased risk of hospitalization for an ACSC (depression alone: Hazard Ratio [HR]: 1.33, 95 % Confidence Interval [95%CI]: 1.18, 1.52; CIND alone: HR: 1.25, 95%CI: 1.10, 1.41; dementia alone: HR: 1.32, 95%CI: 1.12, 1.55; comorbid depression and CIND: HR: 1.43, 95%CI: 1.20, 1.69; comorbid depression and dementia: HR: 1.66, 95%CI: 1.38, 2.00). Depression (Odds Ratio [OR]: 1.37, 95%CI: 1.01, 1.84), comorbid depression and CIND (OR: 1.98, 95%CI: 1.40, 2.81), or comorbid depression and dementia (OR: 1.58, 95%CI: 1.06, 2.35) were independently associated with increased odds of rehospitalization within 30 days after hospitalization for pneumonia, CHF, or MI.

CONCLUSIONS

Depression, CIND, and dementia are each independently associated with potentially preventable hospitalizations in older Americans. Older adults with comorbid depression and cognitive impairment represent a particularly at-risk group that could benefit from targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Aronow WS. Heart disease and aging. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:849–862.

Caspersen CJ, Thomas GD, Boseman LA, Beckles GLA, Albright AL. Aging, diabetes, and the public health system in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1482–1497.

American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033–1046.

Kuehn BM. Cutting Medicare costs will require multipronged approach. JAMA. 2013;309:1334–1335.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html Accessed May 23, 2014.

Niefeld MR, Braunstein JB, Wu AW, Saudek CD, Weller WE, Anderson GF. Preventable hospitalizations among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1344–1349.

Fry AM, Shay DK, Holman RC, Curns AT, Anderson LJ. Trends in hospitalization for pneumonia among persons aged 65 years or older in the United States, 1988-2002. JAMA. 2005;294:2712–2719.

Yan LL, Daviglus ML, Liu K, et al. Midlife body mass index and hospitalization and mortality in older age. JAMA. 2006;295:190–198.

Robinson S, Howie-Esquivel J, Vlahov D. Readmission risk factors after hospital discharge among the elderly. Popul Health Manag. 2012;15:338–351.

Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalizations for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309:355–363.

Zivin K, Pirraglia PA, McCammon RJ, Langa KM, Vijan S. Trends in Depressive Symptom Burden Among Older Adults in the United States from 1998 to 2008. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1611–1619.

Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:427–434.

Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1326–1334.

Mitchell SE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Forsythe SR, et al. Post-discharge hospital utilization among adult medical inpatients with depressive symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:378–384.

Burke RE, Donzé J, Schnipper JL. Contribution of psychiatric illness and substance abuse to 30-day readmission risk. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:450–455.

Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307:165–172.

Davydow DS, Katon WJ, Lin EHB, et al. Depression and risk of hospitalizations for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:921–929.

Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 2002;288:1475–1483.

Health and Retirement Study: Sample sizes and response rates. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/sampleresponse.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2014.

Steffick DE. Documentation of affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Survey Research Center; 2000.

Langa KM, Valenstein MA, Fendrick AM, Kabeto MA, Vijan S. Extent and cost of informal caregiving for older Americans with symptoms of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:857–863.

Zivin K, Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, et al. Depression among older adults in the United States and England. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2010;18:1036–1044.

Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the health and retirement study and the aging, demographics, and memory study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(Suppl 1):i162–i171.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL. A new method for classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Quality Indicators - Guide to Prevention Quality Indicators: Hospital Admission for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001. AHRQ Pub No. 02-R0203.

Coffey R, Barrett M, Houchens R, et al. Methods Applying AHRQ Quality Indicators to Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Data for the Seventh (2009) National Healthcare Quality Report. HCUP Methods Series Report #2009-01. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. August 2009.

Aronsky D, Haug PJ, Lagor C, et al. Accuracy of administrative data for identifying patients with pneumonia. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20:319–328.

Saczynski JS, Andrade SE, Harrold LR, et al. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying heart failure using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 1):129–140.

Kiyota Y, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Cannuscio CC, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Accuracy of Medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction: estimating positive predictive value on the basis of review of hospital records. Am Heart J. 2004;148:99–104.

Allison PD. Survival analysis. http://www.statisticalhorizons.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Allison_SurvivalAnalysis.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2014.

Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:15–19.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27.

Okura T, Plassman BL, Steffens DC, Llewellyn DJ, Potter GG, Langa KM. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of institutionalization and death: the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:473–481.

Okura T, Langa KM. Caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with cognitive impairment: the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:116–121.

Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:763–770.

Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794.

Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Dong X, Leurgens SE, Evans DA. Cognitive decline after hospitalization in a community population of older persons. Neurology. 2012;78:950–956.

Davydow DS, Hough CL, Levine DA, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Functional disability, cognitive impairment, and depression after hospitalization for pneumonia. Am J Med. 2013;126:615–624.

Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–226.

Penninx BW, Kritchevsky SB, Yaffe K, et al. Inflammatory markers and depressed mood in older persons: results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:566–572.

Bindman AB, Chattopadhay A, Auerback GA. Interruptions in Medicaid coverage and risk for hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:854–860.

Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d671.

Byles J, Young A, Furuya H, Parkinson L. A drink to healthy aging: The association between older women’s use of alcohol and their health-related quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1341–1347.

Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845.

Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1042–1049.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–2321.

Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620.

Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2148–2157.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The Care Transitions Intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–1828.

Brock J, Mitchell J, Irby K, et al. Association between quality improvement for care transitions in communities and rehospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2013;309:381–391.

Acknowlegdements

The Health and Retirement Study was performed at the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. We appreciate the expert programming of Laetitia Shapiro at the University of Michigan.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants KL2 TR000421, K08 HL091249, R01 AG030155, and U01 AG09740 from the National Institutes of Health.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Katon has received honorariums for CME lectures from Eli Lilly, Forest, and Pfizer pharmaceutical companies. Drs. Davydow, Zivin, Pontone, Chwastiak, Langa, and Iwashyna have no relevant potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or the US government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Dr. Davydow has had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davydow, D.S., Zivin, K., Katon, W.J. et al. Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations in a Prospective Cohort Study of Older Americans. J GEN INTERN MED 29, 1362–1371 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2916-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2916-8