ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Adverse drug events after hospital discharge are common and often serious. These events may result from provider errors or patient misunderstanding.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the prevalence of medication reconciliation errors and patient misunderstanding of discharge medications.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study

SUBJECTS

Patients over 64 years of age admitted with heart failure, acute coronary syndrome or pneumonia and discharged to home.

MAIN MEASURES

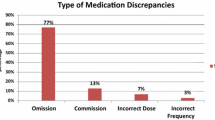

We assessed medication reconciliation accuracy by comparing admission to discharge medication lists and reviewing charts to resolve discrepancies. Medication reconciliation changes that did not appear intentional were classified as suspected provider errors. We assessed patient understanding of intended medication changes through post-discharge interviews. Understanding was scored as full, partial or absent. We tested the association of relevance of the medication to the primary diagnosis with medication accuracy and with patient understanding, accounting for patient demographics, medical team and primary diagnosis.

KEY RESULTS

A total of 377 patients were enrolled in the study. A total of 565/2534 (22.3 %) of admission medications were redosed or stopped at discharge. Of these, 137 (24.2 %) were classified as suspected provider errors. Excluding suspected errors, patients had no understanding of 142/205 (69.3 %) of redosed medications, 182/223 (81.6 %) of stopped medications, and 493 (62.0 %) of new medications. Altogether, 307 patients (81.4 %) either experienced a provider error, or had no understanding of at least one intended medication change. Providers were significantly more likely to make an error on a medication unrelated to the primary diagnosis than on a medication related to the primary diagnosis (odds ratio (OR) 4.56, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 2.65, 7.85, p < 0.001). Patients were also significantly more likely to misunderstand medication changes unrelated to the primary diagnosis (OR 2.45, 95 % CI 1.68, 3.55), p < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Medication reconciliation and patient understanding are inadequate in older patients post-discharge. Errors and misunderstandings are particularly common in medications unrelated to the primary diagnosis. Efforts to improve medication reconciliation and patient understanding should not be disease-specific, but should be focused on the whole patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–7.

Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL, Fine N, Marchesano R, Etchells EE. Frequency, type and clinical importance of medication history errors at admission to hospital: a systematic review. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173(5):510–5.

Lee JY, Leblanc K, Fernandes OA, et al. Medication reconciliation during internal hospital transfer and impact of computerized prescriber order entry. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(21098753):1887–95.

Bell CM. Unintentional discontinuation of long-term medications for chronic diseases after hospitalization. Healthc Q. 2007;10(2):26–8.

Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306(8):840–7.

Bell CM, Rahimi-Darabad P, Orner AI. Discontinuity of chronic medications in patients discharged from the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):937–41.

Perren A, Previsdomini M, Cerutti B, Soldini D, Donghi D, Marone C. Omitted and unjustified medications in the discharge summary. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(3):205–8.

Wohlt PD, Hansen LA, Fish JT. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(10):1611–6.

McMillan TE, Allan W, Black PN. Accuracy of information on medicines in hospital discharge summaries. Intern Med J. 2006;36(4):221–5.

Grimes TC, Duggan CA, Delaney TP, et al. Medication details documented on hospital discharge: cross-sectional observational study of factors associated with medication non-reconciliation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(21284705):449–57.

Himmel W, Tabache M, Kochen MM. What happens to long-term medication when general practice patients are referred to hospital? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50(8803514):253–7.

Stewart S, Pearson S. Uncovering a multitude of sins: medication management in the home post acute hospitalisation among the chronically ill. Aust N Z J Med. 1999;29(2):220–7.

Makaryus AN, Friedman EA. Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(16092576):991–4.

Holloway A. Patient knowledge and information concerning medication on discharge from hospital. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24(6):1169–74.

Calkins DR, Davis RB, Reiley P, et al. Patient–physician communication at hospital discharge and patients’ understanding of the postdischarge treatment plan. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(9):1026–30.

Kerzman H, Baron-Epel O, Toren O. What do discharged patients know about their medication? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(3):276–82.

Maniaci MJ, Heckman MG, Dawson NL. Functional health literacy and understanding of medications at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(5):554–8.

Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(7):e1–157.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Joint ESCAAHAWHFTFftRoMI. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Hear J. 2007;28(20):2525–38.

Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur J Hear Fail. 2008;10(10):933–89.

Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27-S72.

Sunderland T, Hill JL, Mellow AM, et al. Clock drawing in Alzheimer’s disease. A novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(8):725–9.

van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626–33.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–28.

Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(8):771–80.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

The authors would like to acknowledge Amy Browning and the staff of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation Follow Up Center for conducting patient interviews, Mark Abroms and Katherine Herman for patient recruitment and screening, Peter Charpentier for website development, and the other members of the DISCHARGE study team: Ursula Brewster, MD, Christine Chen, MD, Grace Y. Jenq, MD, Sandhya Kanade, MD, Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, and John P. Moriarty, MD.

Funders

At the time this study was conducted, Dr. Horwitz was supported by the CTSA Grant UL1 RR024139 and KL2 RR024138 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research, and was a Centers of Excellence Scholar in Geriatric Medicine by The John A. Hartford Foundation and the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Horwitz is now supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. This work was also supported by a grant from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (P30AG021342 NIH/NIA).

Prior Presentations

An earlier version of this work was presented as a poster at the American College of Cardiology 60th Annual Meeting in New Orleans, LA in April, 2011.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author Contributions

Dr. Horwitz had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Horwitz. Acquisition of data: Ziaeian. Analysis and interpretation of data: Ziaeian, Araujo, Van Ness, Horwitz. Drafting of the manuscript: Ziaeian and Horwitz. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Araujo and Van Ness. Approval of final manuscript for submission: Ziaeian, Araujo, Van Ness, Horwitz. Statistical analysis: Van Ness. Study supervision: Horwitz.

Financial Disclosure

None reported.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ziaeian, B., Araujo, K.L.B., Van Ness, P.H. et al. Medication Reconciliation Accuracy and Patient Understanding of Intended Medication Changes on Hospital Discharge. J GEN INTERN MED 27, 1513–1520 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2168-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2168-4